Majority Of Republicans Say Higher Education Has “Negative Effect” On The Country

The Pew Research Center yesterday published the results of a study showing that “a majority of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents (58%) now say that colleges and universities have a negative effect on the country, up from 45% last year. By contrast, most Democrats and Democratic leaners (72%) say colleges and universities have a positive effect, which is little changed from recent years.”

The survey, conducted in June, was of 2,504 adults.

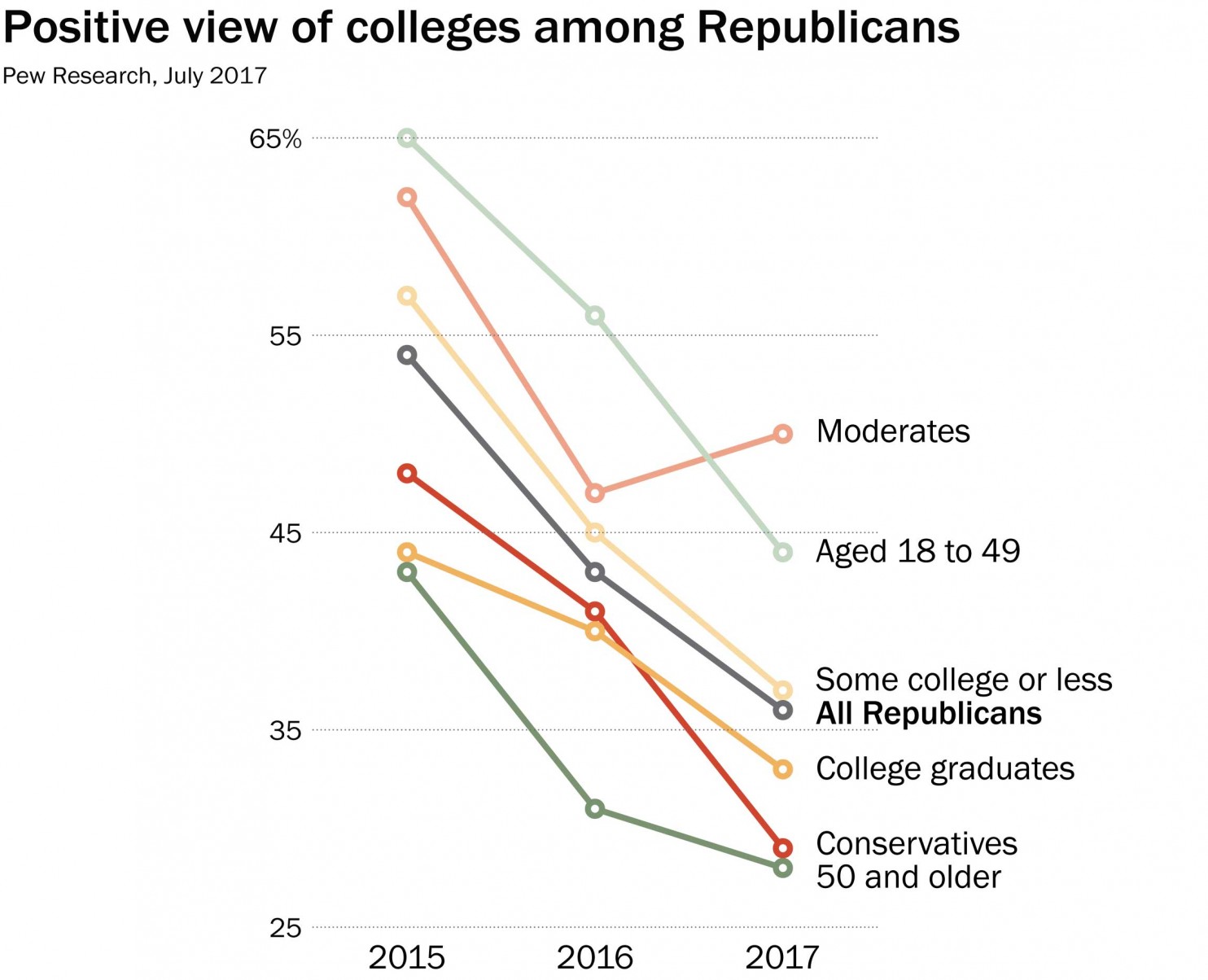

A more fine-grained look at the results suggest that older Republicans have a more negative view of higher education than younger ones:

Among Republicans and Republican leaners, younger adults have much more positive views of colleges and universities than older adults. About half (52%) of Republicans ages 18 to 29 say colleges and universities have a positive impact on the country, compared with just 27% of those 65 and older. By contrast, there are no significant differences in views among Democrats by age, with comparable majorities of all age groups saying colleges and universities have a positive impact. Views of the impact of colleges and universities differ little among Republicans, regardless of their level of educational attainment. Democrats with higher levels of education are somewhat more positive than are those with less education, but large majorities across all groups view the impact of colleges positively.

The study itself does not identify the causes of the negative view, though a few commentators suggest it is owed to recent media coverage, particularly in right-wing outlets, of colleges and universities that depict as bastions of political correctness or liberal bias.

For example, Philip Bump, in The Washington Post, offers this explanation of the data:

Why? Certainly in part because conservative media focused its attention on the idea of “safe spaces” on college campuses, places where students would be sheltered from controversial or upsetting information or viewpoints. This idea quickly spread into a broader critique of left-wing culture, but anecdotal examples from individual universities, such as objections to scheduled speakers and warnings in classrooms, became a focal point.

Clara Turnage, summarizing in The Chronicle of Higher Education the views of Neil Gross, a sociology professor at Colby College, writes:

For years, higher education has been viewed favorably by liberals and less so by conservatives, Mr. Gross said, but political controversies in the past year have drawn attention and increased the negative perception. Protests and incidents of speakers being actively opposed or threatened by students are widely reported, he said, and are often one of the few ways in which the general population encounters college campuses.

The same article quotes Sean Westwood, an assistant professor of social science at Dartmouth College:

There is a perception that Democratic elites are well-educated and Republicans are more of the common man… Colleges are simply seen as a production facility for Democratic beliefs and Democratic ideology.

What to do about this?

Here’s one thing:

Dear academic colleagues on the right:

Don’t cooperate with the Fox News demonization of higher education.https://t.co/UR9tKMlU45

— Jacob T. Levy (@jtlevy) July 10, 2017

I think that advice applies across the board. It is not just some folks on the right that have cooperated with the narrative (which media of all stripes has an inventive to promote) of college campuses overrun by politically correct student-tyrants regularly shutting down or chilling objectionable speech, shepherding each other away from scary ideas into safe spaces, and trying to get faculty fired. Yes these things happen, but, to repeat myself:

we have to be careful here. A (defeasible) rule of thumb is that if you are hearing a lot about an event on the news or social media, it must not be that common (for if it were, then it wouldn’t be newsworthy). There’s also the availability heuristic to be on the lookout for, that is, “the tendency to judge the frequency or likelihood of an event by the ease with which relevant instances come to mind.” Also, let’s admit, it feels good to complain about stuff.

We should not be complicit with the conservative depiction of what colleges are like. That said, when we do come across actual problems that fit with that depiction, we need to be careful to not let political preferences overrun our better judgment.

Your thoughts welcome.

NOTE: It has been a while since I’ve reminded readers of the comments policy. If your comment isn’t showing up, there’s a good chance it isn’t abiding by the policy.

While much of it may be down to the demonisation of college campuses in right-wing media, which may not be an accurate representation of Universities on the whole, it probably stems from a longer running view in conservative circles that the humanities are stacked with the left, which may actually be an accurate representation. The general line has always been that academics ‘tend to lean to the left’, but this completely discounts the kinds of pressures that encourages students to ‘self-select’ away from disciplines that they perceive will present them with greater obstacles to career advancement and success. The left staked its territory in the humanities and social sciences a long time ago, and while many of those with right wing views might have different priorities, like business and finance related jobs in the private sector, they face a bit of an uphill battle bringing conservative values in to something like sociology. There are all sorts of subtle ways the University system weeds them out. I think conservatives see it as a lost battle-ground, that is not a welcoming place where they can explore their views, or that represents them.

Do conservatives think that higher education has a negative effect on the country, as the title indicates, or that colleges and universities do?

“A foreigner visiting Oxford or Cambridge for the first time is shown a number of colleges, libraries, playing fields, museums, scientific departments and administrative offices. He then asks ‘But where is the University? I have seen where the members of the Colleges live, where the Registrar works, where the scientists experiment and the rest. But I have not yet seen the University in which reside and work the members of your University.”

That’s funny but irrelevant to my question. To be a bit more explicit, the question in the poll appears to have been about the effects of colleges and universities on the country, not the effects of higher education. There is a difference between (i) “I think colleges are bad for the country” and (ii) “I think higher education is bad for the country.” Obviously one can support higher education while thinking that colleges and universities are fumbling the ball.

Look, “higher education” is regularly used as a synonym for “colleges and universities.” That’s all that’s going on here.

I think it’s unwise to dismiss this point so quickly. Question wording can have a huge impact on survey responses. For instance, it’s been found that just 25% of Americans will say the government spends too little on welfare, but 65% will say that government spends too little on assistance to the poor. It’s also been found that 55% would have the United States forbid public speeches against democracy, but fully 75% would have the U.S. not allow such speeches (this is from 1941). Any good book on survey science is replete with such examples. This is why, when reporting and discussing survey results, it really is important to stick closely to the question which was actually asked as possible. You just don’t know what would have happened if you asked respondents a different question.

In this case, the question was whether colleges and universities have a negative or positive effect on how things are going in this country. Pew did not ask whether higher education had a negative or positive effect on the country. These are different questions, and for all we know might receive significantly different responses. So we don’t really know what Republicans would say in response to this latter question.

Now, this might seem a bit pedantic. But I don’t really think it is. Survey results often express very ill-formed, uncrystallised attitudes — if they express attitudes at all. Ignoring nuances like these (viz. the effects of question wording) serves to elide this. More solidly, different question wording might serve to elicit attitudes about different things. I suppose B was suggesting that Republicans attitudes towards particular institutions differ from those towards the fact people get higher education, or something like that. If so, and if you want to understand or change Republican attitudes as they actually are, it’s important not to confuse the two.

“Question wording can have a huge impact on survey responses.”

You don’t say?Folks, please note that I did not construct this survey or ask people its questions. Rather, I’m reporting the survey results to academics—people who by and large understand “higher education” to mean “colleges and universities.”

This thing that you’re doing… it’s like hearing a study of the ill effects of cigarette smoking reported as “Study Says Smoking Is Bad For People” and you replying, “this is innacurate, because there is something that people could smoke that would not be bad for them. Smoking is distinct from cigarette smoking. #notallsmoking.” Um, sure, but virtually no one reading “Smoking Is Bad For You” was confused as to what the study was about.

So yes, B and Adam, you’re right — the survey was not about all the various possible ways of learning stuff after high school; it was about higher education in its most prevalent forms: colleges and universities. But you’re wrong to think this was a point on which most anyone reading about it here was confused.

The heading comment was sort of a stretch, but surely there are less antagonistic ways of pointing that out.

What? Gilbert Ryle not withstanding. How is this responsive to the issue?

Part of the problem has to be that conservatives often don’t feel at home in universities. Say ~50% of the country is Republican and ~10% of university faculty are (cf., Haidt, others). That’s a huge disconnect. Repairing that would go a long way toward repairing this negativity.

What does that mean in practice? Don’t know. But even 15% faculty representation would be a +50% increase, which is ginormous. And it’s not like this is a call for equal playing time for pernicious views–to say otherwise is patently uncharitable–but rather a call for (better) balance. Liberals, of course, would also benefit from this balance through being challenged and having stronger foils for their own views, plus preparation for the real world with substantially more disagreement–and less echo chamber–than their college experiences indicate.

It’s not just that there’s a passively default left-leaning orthodoxy. It’s the fact that the left on many campuses (campii?) are openly and actively hostile to anything labelled “conservative” or “republican”. Reports, surveys, and studies on this question abound, as far back as the early 2000’s (e.g.: http://www.mrctv.org/blog/liberal-professors-admit-theyd-discriminate-against-conservatives and http://www.nationalreview.com/corner/433559/yes-universities-discriminate-against-conservative-scholars and http://dailybruin.com/2017/01/18/conservative-students-face-discrimination-marginalization-at-ucla/ and http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A8427-2005Mar28.html and http://www.newyorker.com/science/maria-konnikova/social-psychology-biased-republicans — Heterodox Academy has many more sources for this). And, it’s the fact that administrations are more or less enabling the hostility by refusing to sanction it.

So, what would one expect, in a survey of this nature? Imagine this scenario:

Survey Taker: “Person X has been aggressive and hostile to you for decades. He has threatened you, your job, and your loved ones repeatedly, for various major and minor ideological disagreements. Do you now think this person is a net positive or a net negative in your life?”

Respondent: “Oh, I think it’s a net positive! I really enjoy being threatened, demeaned, and discriminated against! It’s a real character builder!”

Of course we’d all think the respondent was bloody bonkers.

So your theory, then, is that the survey results are just chickens coming home to roost after years of university to right wing students. The problem with this explanation is that, as you yourself note, this hostility has existed for decades; however, the hostility toward the university is among conservatives is quite recent, having emerged in only the last two years. Given that you have a change in attitude without change in (purported) hostility, it seems the hostility can’t explain the attitudes. Maybe the hostility is a necessary condition for the hostility, but demonstrating that would require further argument. And, at the very least, these claims about hostility fail as an explanation of the survey results.

As you wish:

“…Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security. — Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government…”

My claim was about the adequacy of empirical explanations. It is not clear to me how this quotation is supposed to function as a reply to my claim. There must be quite a few tacit premises in your argument that I am missing.

To address your original question, possibly social media is behind the change in attitude? It makes it easier to publicize instances of anti-conservative bias and therefore magnify their impact on public perception (with the attendant problems of social media echo chambers reinforcing confirmation bias, and I say that as someone who fully holds that anti-conservative bias IS a serious problem in academia).

It also serves to magnify the incidents themselves, its much easier for minor local controversies to go viral, for protests and open letters to quickly garner large numbers of participants, it makes for hate mail and harassment faster and easier etc.

Granted social media is older than 2 years so it can’t be the sole reason but I’m still certain it is a factor

I don’t think Haidt is actually a Republican:

https://www.quora.com/Does-Jon-Haidt-vote-Republican

He’s not, but so what?

“The study itself does not identify the causes of the negative view, though a few commentators suggest it is owed to recent media coverage, particularly in right-wing outlets, of colleges and universities that depict as bastions of political correctness or liberal bias.”

Another explanation is that the media coverage is seen as confirming what some conservatives have been saying for decades—that the academy, and the humanities and social sciences in particular, have become home to a particular political ideology that conservatives reject. And so far, the data looks to be confirming that assessment (cf. the material that the Heterodox Academy has been drawing together over the last two years, and that others in this discussion are drawing attention to). In research discussed here concerning the political perspectives of the members of the Society for Experimental Social Psychology (900 members, 335 responses):

http://quillette.com/2017/07/06/social-sciences-undergoing-purity-spiral/

nearly 90% of respondents identified as left-of-center, and 38% identified as one of the two left-most points on an eleven point scale. That’s a striking homogeneity among one of the more important social science organizations–and because new members must be nominated by current members, the homogeneity becomes institutionalized! And the Heterodox Academy is doing a pretty decent job of showing how this political homogeneity distorts the work coming out of the academy. So, one explanation for the negative view conservatives have of today’s academy is that, at least in some cases, they are reacting to an accurate (from their perspective) assessment of the political situation.

And so if the media is a ‘cause’ of the right’s negative views on today’s academy, it’s a cause that’s mediated (at least in part) by the fact that the teaching and research coming out of the academy is indeed (in some ways) at odds with conservative standpoints.

We aren’t going to put a stop to conservative demonization of academia, but there are some things we can do to to lessen its effectiveness.

1. Stop demonizing conservatives.

2. Write in venues where our work is liable to be read by conservatives, on issues that are likely to be of interest to them. Don’t preach. Consider arguments on each side.

3. Listen to what conservatives say, instead of just listening to other liberals critiquing conservatives.

4. Do not support attempts to prevent unpopular opinions being expressed on campus. Criticise such attempts.

5. Set up courses in Working Class Studies. A lof of conservatives are working class folks and the working class is exploited and oppressed. Many of them have the identities “white”, “American” and “Christian”, which influences their voting, but have no working class identity.

6. Speak about the problems facing the working class. Make it clear that you think of a working class white guy as someone much less privilidged than a tenured profesor.

White Christianists in the United States have been fostering distrust of higher education for decades. It seems that their efforts are really bearing fruit now because they’ve had time to poison the minds of at least an entire generation, and on top of that things are coming to a head politically such that people are forced to choose sides in a polarized environment.

The basic strategy is simple. If you have an ideological agenda, you can defend it by serially rebutting each argument made against it, or you can inculcate distrust in anyone (seen to be) in conflict with the ideology. It’s much quicker and more efficient to choose the later strategy. That’s why white Christianists use it. Just as an example, consider this classic: _The Veritas Conflict_ (https://www.amazon.com/Veritas-Conflict-Shaunti-Feldhahn/dp/157673708X). It’s the story of a Christian at Harvard who discovers to her dismay that everyone who disagrees with her ideology is literally possessed by demons. This is not an isolated example. Frank Peretti’s best-selling trilogy (This Present Darkness, Piercing the Darkness, & Prophet) also centers on universities full of demon-possessed liberals. The _Left Behind_ series isn’t quite as virulent, but it takes the same perspective. I could go on.

The bottom line here is simple: if you raise an entire generation to believe that their professors are maybe demon-possessed, they won’t trust their professors. And if you really force them to choose whom to trust, they’ll side against their professors. That’s what has happened in the United States.

This isn’t idle speculation. I should know: it’s how I was raised.

That second paragraph, with only a few noun substitutions, could apply just as accurately to quite a few avowedly left-wing professors I know. Seems to me like they’re using the same strategy.

Yes, nouns like ‘demon’. SMH.

Two contrasts:

1a) Possibly *the* central political issue in contemporary academic philosophy (and probably academia more widely) is diversity along race/gender/sexuality lines. Partly this is argued for on the grounds that a wide range of viewpoints is healthy for students and for research. But in addition, it’s more or less taken as read that the statistics conclusively establish that underrepresentation is a consequence of various forms of injustice, discrimination, and implicit/explict bias. Indeed, implicit bias in particular is so normalised as an explanation that it finds its way into the APA’s Code of Conduct despite reasonably serious scientific question-marks over it. Conversely, it’s actually fairly difficult to even explore explanations based on differential ability or interest without being shouted down.

1b) Representation in philosophy by conservatives is at least as low as for most of the underrepresented groups normally discussed. But the viewpoint-based arguments for this being a bad thing are usually dismissed, and most people give explanations of underrepresentation based solely or primarily on conservatives’ supposed differential interest in or aptitude for academic study. That’s despite the fact that Implicit Association Tests give a stronger effect for liberal/conservative implicit bias than for race- or gender-based implicit bias.

2a) A plausible runner-up for “central political issue in contemporary academic philosophy (and probably academia more widely)” is acts of explicit gender/race/sexuality-based discrimination and harassment, most notably sexual harassment. It is pretty much consensus that philosophy has huge problems with this; for understandable reasons of data collection, there isn’t much systematic evidence. There are, however, lots of anecdotes; many, but by no means all, are anonymous. Individual stories often get very large amounts of attention, with the tone of the discussion being both that the individual event is terrible and that it is symptomatic of philosophy’s (or, more broadly, academia’s) broken culture. Attempts to argue that these are isolated incidents, and that it’s dangerous to generalise from them, get short shrift.

2b) There are hundreds of anecdotes of various forms of viewpoint discrimination and free-speech violation against conservatives on campus, some of which have been extremely severe (even violent) and involved large numbers of students. But when they happen, discussions are much more nuanced; a substantial minority will actively defend the event, others will offer pretty luke-warm criticism, and it’s respectable to claim (as Justin does in the OP) that we should be very cautious about generalising from individual stories.

If I were a conservative (I’m not, FWIW), I think I’d look at this and find it difficult to take in good faith academics’ protestations that there is no significant anti-conservative bias on campus.

I’d like to strongly endorse this comment, and also add that while it is in important to not over-generalize from anecdotes it is worth keeping in mind that in addition to the direct impact on the individuals involved incidents of anti-conservative bias/hostility (and any other type of specific anti-group bias/hostility sexism, racism etc) the is also a chilling effect, on those who witness/hear about it and who then decide to keep their views [on certain topics] to themselves among colleagues or in a classroom, not publishing on certain topics, not lecturing on certain topics, not attending certain conferences, not asking certain questions at conferences etc. I’d imagine the extent of this would be hard to measure but is I suspect significant

Isn’t this easy? The more educated a person, the less likely to support Trump and republican short-sighted views?

This reminds me of criticisms of the humanities and responses thereto–and these are related. It seems to me that many academicians are jumping to defend the university, as some have jumped to defend the humanities. To my mind, the first step in both cases ought to be to acknowledge that the criticisms afoot are largely reasonable (which is consistent with them being false/invalid). It can’t be a secret that even many liberal academicians think that universities–and especially the humanities and social sciences–are largely in the grip of a movement that is (leftist) anti-liberal on its political side and anti-rational on its intellectual/ theoretical/ philosophical side. And: they think those things are bad. Of course, many academicians (including many here) disagree–they disagree that the movement is anti-liberal, or they agree that it’s anti-liberal but think that’s a good thing to be (from the left, anyway). We won’t settle the deep disagreements in this discussion, of course. But what surprises me is that anyone could possibly find it surprising that conservatives would have negative views about the the academy (or at least/especially the humanities) given the facts about what *does* at least *seem* to be going on in them. Defenses of the university generally–like defenses of the humanities–that fail to at least acknowledge the source of much of the current criticism are likely to fail (and possibly *should* fail.) Even if you think that the appearances are deceiving–or if you think that they aren’t, but that what’s happening is good–you really shouldn’t be surprised that many people disagree with you about those things–nor that changing their minds will probably require acknowledging that their criticisms aren’t *crazy.*

Furthermore, it is reasonable to believe (which is, again, consistent with it being false) that many doctrines of the movement in question–political correctness or whatever you prefer to call it–are very, very far to the left. And therefore, again, it should not be a surprise that many closer to the center or further to the right find them alarming–and think that even a little goes a very long way. Just to take one prominent example, it certainly *seems* that this movement seeks to restrict–or let’s say *enthusiastically discourage*–the expression of views that conflict with its orthodoxies. It simply *cannot* be a surprise that people find this alarming. They *ought* to find it alarming. Perhaps their fears can be shown to be unfounded or otherwise confused–but how can anyone not find them at least reasonable?

(Incidentally, I expect that saying that universities have an (overall?) negative impact on the nation is really just a way of expressing disapproval.)