Psychologists Test Kant’s Aesthetics

The experience of beauty is a pleasure, but common sense and philosophy suggest that feeling beauty differs from sensuous pleasures such as eating or sex. Immanuel Kant claimed that experiencing beauty requires thought but that sensuous pleasure can be enjoyed without thought and cannot be beautiful. These venerable hypotheses persist in models of aesthetic processing but have never been tested.

Until now.

Denis Pelli, a psychologist at New York University, and Aenne Brielmann, a psychology graduate student who works in Pelli’s lab (and whose interesting-sounding PhD work is on “empirical aesthetics”), have run a series of experiments testing Kant’s hypoetheses. Their results, published in Current Biology, are, in sum:

We confirm Kant’s claim that only the pleasure associated with feeling beauty requires thought and disprove his claim that sensuous pleasures cannot be beautiful.

Science Daily has a helpful description of what the Pelli and Brielmann did:

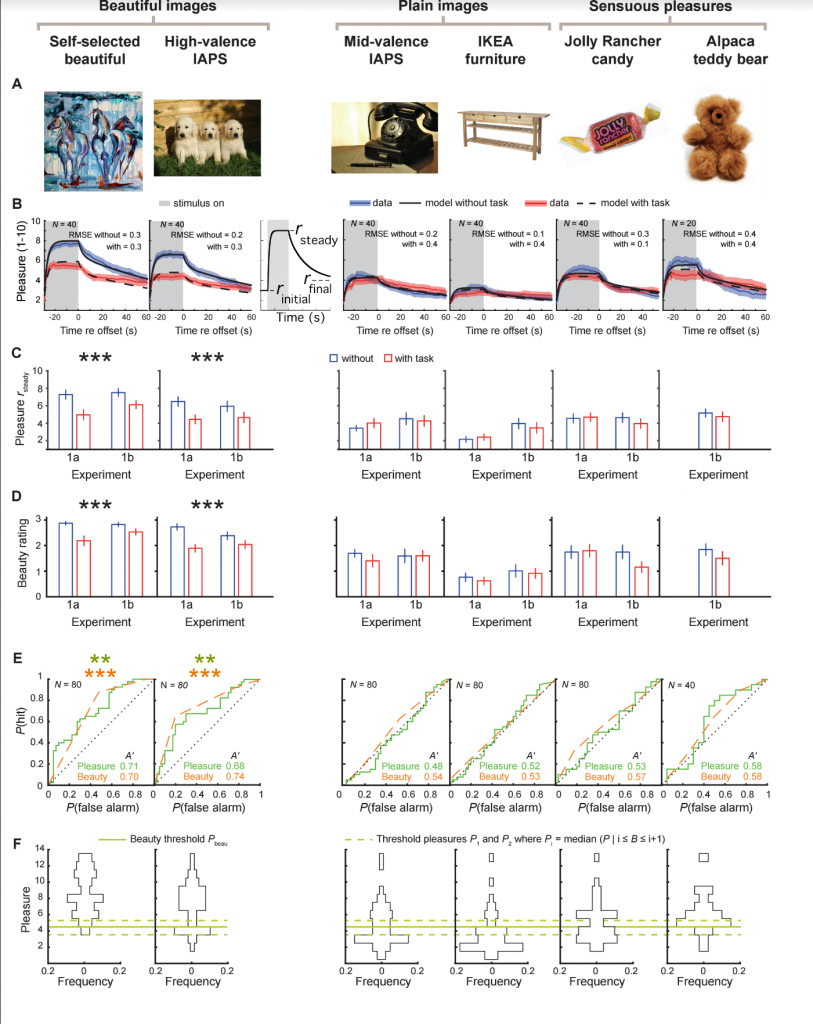

To explore these philosophical theories in the new study, Pelli and Aenne Brielmann asked 62 people to indicate how much pleasure and beauty they felt while they saw an image, tasted a candy, or touched a soft teddy bear. The researchers showed each person many different images, some beautiful, some merely nice, and others neutral, like a chair in a furniture catalog. Participants then rated their experience of each object on a four-point beauty scale.

In another round of the same experiment, participants were asked to repeat what they’d done earlier, this time while they were distracted with a secondary task. In that task, participants heard a series of letters and were asked to press a button any time they heard the same letter they’d heard two letters before.

The researchers found that the experience of non-beautiful objects wasn’t changed by the distraction. But, distraction took away from the experience of beauty when a person was shown an image earlier deemed beautiful. In other words, Kant was right. Beauty does require thought.

However, contrary to Kant’s proposal that sensual pleasures can never be beautiful, about 30 percent of participants said they’d definitely experienced beauty after sucking on a candy or touching a soft teddy bear.

Surprised by that, the researchers decided to follow up. They asked some participants who had responded “definitely yes” for beauty on candy trials what they’d meant. As Brielmann and Pelli report, “most of them remarked that sucking candy had personal meaning for them, like a fond childhood memory. One participant replied, ‘Of course, anything can be beautiful.'”

“Our findings show that many other things besides art can be beautiful—even candy,” Brielmann says. “But for maximum pleasure, nothing beats undistracted beauty.”

So, philosophers, does this research show what Pelli and Brielmann thinks it shows?

“feeling beauty in a candy” ? The grammar itself is really weird. At least in my language (French), I’ve never heard someone said that they “felt beauty.” Never heard anyone said that tasting our touching something felt “like beauty” or “beautiful” either.

Yeah, I suspect that people are being primed to report on things in ways they otherwise wouldn’t. Are they really measuring people’s perception of beauty (such as it is), or their willingness to use certain adjectives in conjunction with pleasurable experiences, especially when prompted?

Is there even any evidence of a separate “sense” of “beauty” to begin with? Even this study seems to offer reasons to doubt. E.g.: “The linear relation between beauty and pleasure supports the claim that beauty is interchangeable with “aesthetic pleasure” [10]. The difference between beautiful and non-beautiful pleasures is that the beautiful pleasures are greater.” And from the conclusion: “First, the feeling of beauty increases linearly with pleasure, and strong pleasure is always beautiful, whether produced reliably by beautiful stimuli or only occasionally by sensuous stimuli. “

Alright, the thinking task took away from the pleasure of an experience of the beautiful. They then infer that thought is required for beauty. This seems obvious only if you assume that your level of pleasure is directly related to your experience of beauty. But sure, let’s grant that.

But in the study, the people sucking on candy didn’t actually experience a drop in pleasure when they had to perform the task. How are we to make sense of this given that 30% of candy-suckers thought they experienced beauty? Why is this particular experience of beauty not affected by the task? Perhaps ‘beautiful’ is too inclusive an adjective, and as a result, tracks experiences that are significantly different from what Kant had in mind.

I think the important point here is to distinguish between average responses to the candy and the responses of individuals. If you read the complete results section, you will find:

Participants’ reports of ‘‘definitely’’ experiencing beauty from

non-visual stimuli in trials without added task (37% for candy,

30% for teddy bear) made us wonder whether the occasional

beauty of (usually) non-beautiful stimuli might be like that of

beautiful stimuli, just less frequent. We gauged the task-susceptibility

by the relative frequency of ‘‘definitely’’ feeling beauty with

and without added task. The ratio of instances of definitely

feeling beauty with over without added task was 27/61 = 0.44,

95% CI [0.33, 0.57], N = 80 for beautiful stimuli and 19/28 =

0.68, [0.49, 0.82], N = 140 for non-beautiful stimuli, which are

not significantly different. Thus, the experience of beauty is

equally susceptible to the two-back task, regardless of the nominal

beauty of the stimulus.

For pure pleasure, nothing beats heroin.* But heroin is not beautiful.

(You’d think psychologists of all people would pick up on that. Come on, psychologists, get it together!)

[*] Or so I’m told. See e.g. Reed, Cale, et al., 1967.

If I may make a plug, for those interested in the topic: Aenne Brielmann will be among those speaking at this year’s Society for Philosophy and Psychology meeting (June 28-July 1 at Johns Hopkins). Things kick off with a workshop June 28 on cognitive science and aesthetics, with a variety of well-known philosophers and scientists who work on these issues. For more info, see the SPP website. Click on ‘call for papers’ for info on invited speakers (there are also 60 contributed talks, plus 60 posters). Click on ‘meetings’ for a link for registration.

http://www.socphilpsych.org/meetings.html

In what sense does Kant say judgements of (free?) beauty involve ‘thought’, whereas judgements of the agreeable do not?

So far as I can tell, Kant says the former are based on disinterested satisfaction which results from the the ‘free play’ of the imagination and the understanding. Presumably the authors think that performing a distractor task will inhibit free play, such that anyone performing a distractor task will be unable to make judgements of free beauty. I am unconvinced by this premise. Why think the concentration required to complete the distractor task inhibits the free play of the imagination and the understanding, which is surely an unconscious or subconscious and involuntary process?

This is a logical and structural point that goes back to the First Critique about the requirement of the Categories’ a priori nature to be applied in any instance of synthesis involving empirically given objects. Thus, judgment logically requires some component of thought whereby whatever is judged is not merely something given in experience. (at least that’s my somewhat Sellarsian take on this matter, but I think this holds up from a classical phenomenological reading of Kant as well)

Now, the interesting upshot of this is that some feelings require the activity of judgment in order for these to be produced in the first place: respect and aesthetic pleasure. Respect is only possible if you can recognize the demand the demand that the Categorical Imperative puts on you, which obviously requires Reason and some judgment that the moral law is binding ‘categorically.’ For aesthetic beauty, while there are of course the four particular moments that generally identify when you have a case of aesthetic beauty, it still requires our ‘Urteilskraft’ to engage in an active judgment of reflection on the object in question in order to produce the feeling, or else the feeling could only have a pathological (and I think we can safely read this also as ‘physiological’) origin. (I do not have my copies of the Critiques on hand, but I think referring to the Transcendental Deduction in B, Kant’s analysis of respect in the 2nd Critique, and the deduction of the aesthetic judgment in the 3rd should show what I’m saying to be what Kant thinks on the matter)

As for the distractor element, it might make it more difficult to form a reflective judgment if you are not in a state of mind that allows for free play between sensibility and imagination, but I think it would still be possible to become ‘arrested’ by a particular object that becomes the object of aesthetic reflection (say when you are walking in the woods and a particular something-or-other strikes you as beautiful and ‘draws in your gaze’).

Also, one thing to keep in mind is that Kant singles out natural beauty as paradigmatic examples of objects that occasion that particular feeling when making reflective judgments, which should factor into the experiment as well, i.e. they shouldn’t just show pictures of art-objects (or some such), but rather pictures of landscapes and the like (or even better, plop them in front of the Grand Canyon and see what happens). Kant thought that art-objects are in some sense only beautiful derivatively, because the first instance of when we apply judgment is with objects we find in our environment (and because of the use of reflective judgment as heuristics for structuring scientific endeavours), and because we very often take note of art-objects rather as objects of moral interest rather than aesthetic interest.

I think this experiment doesn’t clearly explain how diminishment of executive function relates to Kant’s understanding of the role of thought in aesthetic experience. It may be the case, for example, that the distracting task merely diverts attentional resources away from the beautiful image, which then decreases the subjects’ experience of it as beautiful. All this experiment would show is that attention is necessary for experiencing (high) levels of beauty, not that thought, in some more robust sense, is necessary. So, maybe full attention on the beautiful image would increase the subjects’ perception of it as beautiful simply because they would then notice a greater number of visually stimulating features of the image, without applying thought to the image as a whole. Furthermore, the fact that the high affective valence images (pictures unlikely to be classified as beautiful by a Kantian, I venture to guess) also decreased in perceived beauty and pleasure in the distraction task trial suggests that something besides thought, on Kant’s understanding of it, is that thing which explains the decrease in judgments of beauty and pleasure.

This does not disprove Kant’s aesthetics. It simply proves that 30% of subjects liked touching the teddy bear.