About Letters of Recommendation

Consider this a space for the discussion of various issues related to letters of recommendations. Here are three:

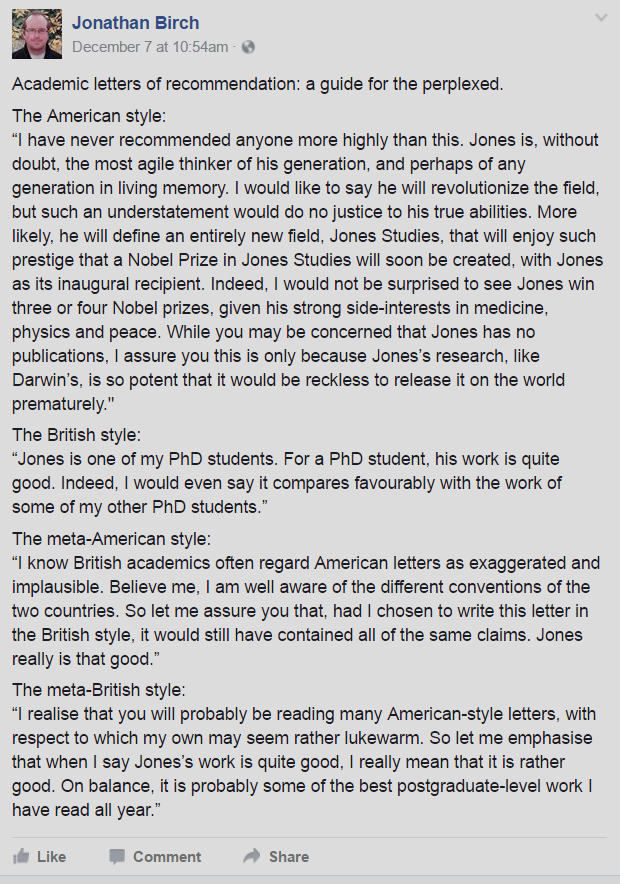

(1) The difference between U.S. and British letters of recommendation. I put the following in the Heap of Links the other day but a reader suggested it would be worth discussing. Here’s Jonathan Birch (LSE) on Facebook last week:

The reader added, “I think this practice genuinely hurts British candidates for US positions.” It’s hard to come by evidence of this, apart from the testimony of those on search committees. Has anyone had experience in making hiring decisions in which the hyperbole of US letters of recommendation / understatement of British letters of recommendation had an undue effect? Has anyone come up with a standard way of accounting for these differences? Perhaps something along the lines of the following chart, but for academics?

(2) The number of letters required. It’s not unusual for job candidates to have five letters of recommendation in their dossier. One can’t help but wonder whether that number brings us to the point at which we’re no longer making good use of people’s time (the candidate who must request the letters, the authors of them, and of course those who are tasked with reading them). I’m tempted to think that we’re at that point above three letters, yet I see how competitive pressures can make it rational for candidates to seek more, particularly if their authors are well-known. If there’s to be a remedy here it will be on the demand side. Departments could just say: “we will accept no more than three letters of recommendation; if more than three are sent, only three will be selected–at random–to be read along with the candidate’s other supporting materials.”

I’d be interested in hearing the justification for requesting more than three letters, as some institutions do.

(3) What is valuable and what’s not in a letter of recommendation? In an essay a few years ago, Jonathan Wolff (UCL) wrote, somewhat exaggerating:

unless a reference is three or four single-spaced pages then the support is regarded as somewhat half-hearted. But usually there is not that much to tell, and so we receive, in effect, six different versions of the candidate’s CV in prose form, combined with summaries of his or her PhD thesis, and a few lines of detail designed to convince that the reference writer really knows the candidate well and has been truly, deeply, impressed… For all the effort and ink, what, as readers of references, do we hope to find? Only this: is the candidate better or worse than it appears from their CV?

Maybe these things could be shorter. Wolff thinks that the “business paragraph” is the one in which comparisons are made:

The rule is that the more the reference writer sticks out his or her neck, the stronger the recommendation. If you say the candidate is good, that means nothing. If you say “in the top three of the cohort”, again, very little. But if you say the candidate is the best this year, or for several years, or for a decade, that means something.

Do readers agree that this is the most important part of a letter of recommendation, generally? Anyone have reservations about the value of these comparisons?

Other questions, concerns, complaints, and advice about letters of recommendation are welcome.

Is this even true for British letters any more? It certainly was true 10-15 years ago. But I thought by now everyone knew these facts, and either adjusted how they wrote letters (esp if British) or how they read letters from different countries. I mean, I’ve been seeing versions of this point about translation for years and years, so it would be surprising if no one had adjusted in over a decade. And I’ve certainly seen much more American-style letters from Britain in the last few years than I had before that.

My guess is that the adjustments have gone so far that British students are subtly helped; people adjust up the letters from Britain more than needed for the sake of fairness. But it’s probably not a big factor any more.

I’ve also occasionally heard some claims about letters from French or German or Italian recommenders, but I have much less basis for evaluating these comparisons myself. Have those also been getting closer to each other due to recent European integration of a lot of the grant funding systems?

I work in continental Europe and in my personal experience, the difference is still very significant. Since I generally apply for European jobs, European letters are not a problem for me (the hiring committees know the jargon). However, whenever my projects are evaluated by a German, Japanese… peer-reviewer, it is X-times more likely that they will receive also negative comments, just because the German, Japanese… peer sees raising criticisms as part of her job. By contrast, US-peers tend to write things like “There is nothing I could suggest to improve the project, which is already amazing/astonishing/…”

This was my first year being on a hiring committee, and I found most letters of recommendation next to useless. Many of them were so verbose and clearly exaggerated that they conveyed almost nothing to me. The letters I found most useful were the ones that said very specific things, e.g., candidate X is the best student I’ve worked with in 20 years as a faculty member, or I project that candidate X will have a career as successful as famous person Y, who was also my student many years ago.

Flowery talk about how amazing philosopher and wonderful person and what a great colleague the candidate would be did not make said candidate stand out from their peers, since pretty much every letter said versions of the same thing.

I think this was the biggest problem for me: for the vast majority of candidates, it was as though I was reading the same letter over, and over again. The effect was that these letters did not help me to discriminate among candidates at all.

I can attest to the American style having hurt *subsequent* candidates’ chances. One letter with clear and specific numerical comparisons – “in the best X% of people in this whole subfield, at any level” – for a candidate that did not in any way live up to the promise. Letters from that whole program now tend to get severely discounted.

For number of letters: 3 or 4 really good letters are great. We have candidates with 10 or even more letters, and this is kind of a dangerous game. Often your recommendations are taken in whole to be only as strong as the weakest letter or two. Adding more people, even if they are big names in the field, who do not really know you and your work incredibly well, and who may also be writing for other candidates this year whose work they do know incredibly well, puts you at a disadvantage. Your letter from famous philosopher X is much weaker than another candidate’s letter from X. Committee members make comparisons across candidates: Philosopher F, for instance, might have written for about 10 candidates in our pool, and we can compare the strength of letter by the same person across different candidates. You can’t check the contents of letters for strength, but don’t add lots of letters unless there really is a good reason.

To clarify: I do not think there should be a firm cap imposed by search committees, nor do I think 3 is the point of diminishing returns. But 10 or 12 is too many.

I am also on a hiring committee for the first time. Slightly disagree about letters not helping sort through candidates, and strongly disagree with the idea of capping the number of letters people can submit and the idea that diminishing returns start c. 3 letters (I would put that around 6 letters, depending on the search).

First off, I was actually surprised by how much letters *helped* discriminate between candidates. We were searching in a fairly narrow area, so lots of the candidates had letters from the same people. It was pretty easy to get a feel for how the letter writers thought about the various candidates, even though they didn’t explicitly compare them. Also, a couple of people’s letters–people who had a lot of letters–were just clearly bounds ahead of all the rest. I think quantity really helped here, since it made it more likely that there was overlap with other candidates and hence easier to evaluate how hyperbolic the letters were.

Second, I consistently found more letters more helpful, up to about 6, where I started getting annoyed. I think having a strong external letter is really, really important. I think having more than one of those–from people who differ intellectually/geographically/etc.–is really impressive (only when the letters are detailed and extremely positive, so this is not a recommendation to candidates). Also, a lot of our candidates were people with really strong strengths in very different areas (and sometimes a different discipline entirely), and it was very useful to hear people attest to their abilities/strengths specifically in those areas.

(Also, our dept. didn’t ask for teaching letters, but if you are doing so, I don’t think that should force candidates to sacrifice a research letter.) I also think having a bunch of letters can help level the playing field for candidates with crappy advisers or problems within their own department.

All that being said I didn’t actually put that much stock in the letters in general! But I found them way more helpful than I expected to going into things. And I think the more the better, up to a point, and so long as they are adding something new to the mix (highlighting a different strength, or training in another field), and not dragging things down by being less strong than the others.

I’m on the application side of the process (and have been for the last 5 years!). One issue with allowing only three letters is that you typically have a letter addressing your teaching abilities. If limited to three, do you include that letter? If the ad doesn’t say (which is typical), what do you do?

Honestly, I don’t see the advantage of limiting the number of letters that applicants can submit. If you don’t want to read all of them, don’t. But if you do, you have all the info.

I share RM’s scepticism about how useful letters are. Actually even the comparative ones (“best student I’ve worked with in 20 years as a faculty member”) are useless, since people are now quite willing to say this person is a future David Lewis/Martha Nussbaum/John Rawls. Everybody has gotten the memo: if you say that X is less than the best philosopher you’ve come across in the last twenty years, what you really mean is that X is no good, and you doom her to unemployment forever.

I personally think that people on hiring committees should start with the writing sample and then go on to letters to see if they help them understand the writing sample in context. If somebody says: the merit of this paper is that it helps us understand why the controversy between externalism and internalism is ill-posed because XYZ, that helps you make up your own mind. Just filter out the evaluative parts of letters.They are just so much noise.

How can the controversy between externalism and internalism be ill-posed because XYZ if externalism motivates itself based on scenarios involving XYZ?

OK, I’ll stop.

I think people on this thread are mostly focused on job letters but if I may I would like to plead for help with letters for graduate school. I have seen job letters now as part of a search committee but since I work at a school without a graduate program I have never seen letters for graduate school. I have no idea what to write in them! Specifically, what do admissions committees most want to know about applicants from less prestigious schools? If I bring up hardships the student has faced does that make them seem less promising? Is it appropriate to discuss their work and explain the philosophical import of papers they have written when they are just an undergraduate? Should I discuss their philosophical interests? Their personality? How long is a good letter? Every time I write one (which is not that often) I wish I could just get on the phone with someone and answer questions and give a straightforward assessment.

I’ve read thousands of such letter. Here’s what I find helpful:

1. demonstrating that you know the student well and have invested time and energy in them

2. Telling me specific things about your interactions with them — points they made in class, something about their writing, etc

3. Explanations of any weaknesses in their transcript (eg, if the GPA is weaker than it should have been and you can point to the two classes that hit it, and explain why she did badly in those classes

4. Yes, I want to know something about their personality, specifically whether she will be a good colleague to other graduate students. We’re creating a class, and the success of each depends partly on the behaviour of others

5. Comparisons with other students either that you are currently teaching, or have gone on in the profession. EG, if she’s about as promising as the student who 3 years ago went to Cornell, say that.

6. Hardships they have faced make them seem more, not less, promising. And the way you write can explain that. The students who have had some success in the face of hardships are the ones who impress me. That might be idiosyncratic, I realise, but I doubt it is.

When reading reference letters I always remember Groucho Marx’s line, “Let me exaggerate further …”

you mean like when your department can’t agree on a single candidate good enough for them?

This is slightly off topic but still, I hope, useful – US grads applying to the UK really should be aware that the cover letter counts for a lot (or, at least, at the places I’ve taught). Indeed I was a bit taken aback by Mohan Matthen’s claim that the most important part of the referee letter is the part which contextualises the writing sample. At least in my experience, US referees tend to spend too long summarising a candidate’s work when what I expect a good applicant to have done that – pithily – in her cover letter. This is not to say that one system is better than the other. It’s more a piece of prudential advice to US candidates the cover letter used for a UK job really should be informative (and focussed – i.e. It’s good to have a letter which shows you’ve done some research into the place you’re applying to, not just replaced Uni of X with Uni of Y – and, if only for the HR people – use the word ‘impact’ once!)

Hi,

I just wanted to ask the following question: Have you ever considered the idea whether letters of recommendation are just a sophisticated way to persuade committees in order to perpetuate some kind of aristocracy in academia ? I mean, once I met a grad student from a top philosophy department who was sure that he will find a really good position just because of his institution. He talked a great deal about the influence of recommendation letters. Of course, he had no publications at that time. On the contrary, I know of excellent grad students from continental Europe, Mediterranean countries (Southern Europe or North African), and South American countries that, despite not having such letters, they have publications in top journals (among other achievements), but it is more difficult for them to find a job. And the main reason must be the institution and the letter. There is no way to tell why someone from a top university with no publications is chosen and one from a humbler university with publications is not, except for the letters and the prestige of the university. Of course there are exceptions sometimes, but they are just a disruption in this unfair process of selection.

I am starting to think that maybe recommendation letters are some kind of mechanism for punishing excellent grad students just because they couldn’t go to top universities for several reasons (budgetary reasons are not the only ones). If so, I think we should get rid of them as a mechanism for perpetuating an academic aristocracy that is totally against the spirit of what Academia should be.

It is perhaps worth pointing out that at some UK institutions (e.g. here at Leeds) search committees do not get to see letters of recommendation, which are only ‘revealed’ to the interview panel at the end of the process. My understanding is that this is because HR see them as a final ‘check’ on a candidate rather than substantially informing the decision. On the one hand, colleagues tend to find this frustrating, as they see it as removing a further potentially helpful piece of information; on the other, it should assuage the concerns of ‘A.’ above in that candidates are primarily evaluated on their papers/writing samples, teaching, proposed research and, regrettably perhaps, grant capture abilities, rather than someone’s ‘flowery’ opinion.

Maybe Leeds is ine of the exceptions, Steven? I guess it is. In that case, it is great.