University of Chicago Issues Massive Trigger Warning

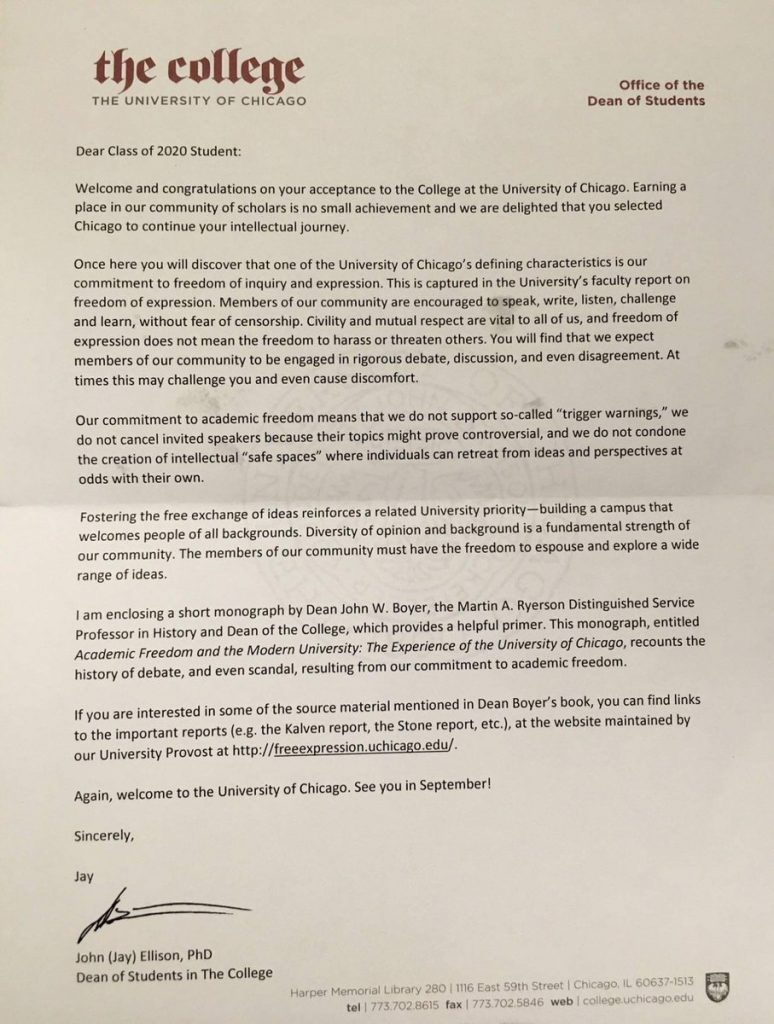

Joining the apparent trend of schools and professors alerting students to the prospects that they will be encountering material they may find upsetting, the University of Chicago this week issued a “trigger warning” to its entire incoming class of first-year students. In a letter to the class of 2020 (reproduced at the bottom of this post), Dean John (Jay) Ellison writes:

You will find that we expect members of our community to be engaged in rigorous debate, discussion, and even disagreement. At times this may challenge you and even cause discomfort.

The term “trigger warnings” was originally introduced to refer to warnings to people with post-traumatic stress disorder about the impending discussion of some widely-recognized causes of trauma. The term is more broadly used now, often overlapping with “content warnings” about course material that a range of people—not just those with trauma-related medical conditions—might find disturbing.

Such warnings have been the subject of some criticism, but the University of Chicago appears to agree with the professor who has perhaps been most outspoken in their defense, philosopher Kate Manne (Cornell). In an essay in The New York Times last year (covered here), Professor Manne wrote:

The point is not to enable—let alone encourage—students to skip these readings or our subsequent class discussion (both of which are mandatory in my courses, absent a formal exemption). Rather, it is to allow those who are sensitive to these subjects to prepare themselves for reading about them, and better manage their reactions.

According to Manne, then, warnings promote the autonomy of the students, allowing them to engage with a broader array of material. Likewise, as part of the justification of the University of Chicago’s warning, Dean Ellison writes that “the members of our community must have the freedom to espouse and explore a wide range of ideas.”

Further, just as Manne does not take the point of these warnings to be to shield students from views they dislike—students “need to learn to engage rationally with ideas, arguments and views they find difficult, upsetting or even repulsive,” she says—Ellison writes that the University of Chicago does not condone the idea that “individuals can retreat from ideas and perspectives at odds with their own.”

Despite the positive publicity Dean Ellison’s letter is getting from some quarters, it is sure to face harsh feedback from those who think that its warning to the students is just further coddling of wimpy millenials.

This is especially so since it is unclear why the students would expect the university to “cancel invited speakers” or create “intellectual ‘safe spaces'”anyway, given just how infrequently such things actually happen.

You can read the dean’s letter in its entirety, here:

(Thanks to David Boonin for a quip that inspired this post.)

“given just how infrequently such things actually happen”

https://www.thefire.org/resources/disinvitation-database/#home/?view_2_sort=field_6|desc

???

Yes, infrequently—as a percentage of the total number of talks at universities, or even as a percentage of the total number of talks on likely controversial subjects at universities.

> “as a percentage of the total number of talks at universities”

obviously

> “as a percentage of the total number of talks on likely controversial subjects”

not so obviously — what’s your basis for this?

View from armchair, I’ll admit. But I’ve been in it for a while, and it does have a pretty good view.

It is worth noting that a number of people in the list are Commencement speakers; opposing an invitation for a commencement speaker is not the same as opposing an invitation for a talk. I would never protest if my university were to invite George W Bush for a talk, but I would also have protested had it invited him to be our commencement speaker; I would not want my university to honour someone who I consider to be a war criminal (and, of course, this has nothing to do with opposing the content of his talk; I am sure Bush delivered a very bland and non-threatening .commencement speech).

And it’s a bit odd to dismiss a concern based on infrequency. It does happen, and it shouldn’t happen. Is there some magic number of incidents whereby something becomes a real concern?

Does it happen more or less often than students get killed by drunk driving on campus? Is it worse than when students get killed by drunk driving on campus? If it is less frequent, and less bad, then it probably doesn’t require *more* concern than drunk driving on campus.

What an impoverished view of how the world, policy making, decision making, and moral decision making work! You’ll need an example that actually works for the point you’re hoping to make.

Is the drunk driving death rate on campus higher or lower than in non-campus areas? How about compared with non-campus areas with comparable population densities? What is the nature of the relation between the university’s mission and drunk driving as opposed to lecture/speaker invites? Other than the campus, what entities are tasked with handling drunk driving rates on campus? Other than the campus, what entities are tasked with handling speaker invites on campus? Assuming drunk driving rates are affected by car ownership and can be contextualized against that broad level backdrop, where does the campus (as opposed to a body like the police or local gov’t) enter “supererogatory” territory with respect to decreasing the drunk driving death rate? Do campus speakers admit of a comparable contextualization?

Also, “concern” is not a zero sum game. We can enact policies that cut down on campus drunk driving while simultaneously addressing issues with speaker (dis)invites. It’s a weird trick called “doing things.” The trick is in…doing them.

I wish the conversation about content warnings hadn’t been pulled so far away from Manne’s original emphasis on accessibility. I’ve only been teaching a few years, and I’ve been repeatedly shocked as to how many of my young students have already suffered trauma like abuse or sexual assault. For all the talk that goes around about coddling and entitlement, these students don’t speak up or protest when they encounter material that invokes their traumatic experiences; they shut down, even if they don’t mean to. And why wouldn’t they? If I can help them without derailing the class — which no one has ever asked me to do — I want to do so. There’s no distinction here between protecting these students and fostering their education.

There are surely meaningful discussions to be had about trigger warnings, safe spaces, and rising rates of disinvitations. (I’d like to know how all these might be connected, perhaps ironically for Ellison, to the corporatization of the university and the student-as-customer.) But we won’t have them if they’re framed as some contest between toughness and fragility, or between people who want freedom and people who don’t.

And what in the world is an “Intellectual safe space”? Does the history of debate at the University of Chicago not include a primer on straw men? Isn’t there too much at stake for this kind of ideological grandstanding? I wish I could laugh, but I’m just saddened by this.

Yes. That is exactly how I feel about this insipid debate. Are we not teachers? And as teachers, should we not care about whether our classrooms are environments in which our students, including those who belong to disadvantaged groups, face avoidable and unfair obstacles to learning? Sure, academic freedom is important, but I don’t see why that ideal is threatened by the pursuit of this basic pedagogical end.

Is this meant to be satire? (The post, that is, not the letter – which is neither a trigger warning nor likely to be opposed by those that think such measures are ‘coddling’.)

My reading is that the post is making a point that even while claiming to be against trigger warnings, the letter itself constitutes, effectively, a trigger warning.

Here is an even more blatant example of a supposed anti-trigger warning trigger warning, by Ilya Somin, who takes himself to be agreeing with U Chicago:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/volokh-conspiracy/wp/2016/08/25/a-warning-against-trigger-warnings/?utm_term=.fd665173139b

(For the record, Somin disputes that claim in the second update – implausibly, it seems to me. I don’t think it’s a problem if it turns out that trigger warnings are extremely common.)

Somin provides, at the start of his course, a single warning that a number of controversial subjects will be discussed, together with a non-exhaustive list of such subjects. Whether this, or the language in the University of Chicago letter, can be characterized as a trigger warning is really beside the point. If such general advice were sufficient, it would show that trigger warnings are not needed, because students who can scan materials for what triggers them in some courses can probably do it in all of them. That is, if the point of trigger warnings is as Manne describes it, either these warnings do not address that point, or very general advice would (which would obviate the need for the types of trigger warning typically discussed).

I’ve always thought of trigger warnings as being exactly what Manne and Somin describe in their courses – both of them give fairly minimal trigger warnings. Like anything of this sort, it comes in degrees. So you can give a minimal trigger warning at the start of a course, but you can also, if you want, give a trigger warning at the start of specific material. As a random example, I tend to give something like a trigger warning before I teach Marilyn McCord Adams’ work on the problem of evil, because of some particularly graphic “horrendous evils” that she describes. I see this as (1) a trigger warning (even though I don’t use the term… and don’t even like it, to be honest) and (2) morally (though not legally) obligatory.

For those who don’t want to visit the WaPo blog, here is the relevant passage:

One of the law school courses I teach at George Mason University is Constitutional Law II, which focuses on the Fourteenth Amendment and its history. The class necessarily addresses many painful and difficult issues. Instead of offering trigger warnings, on the first day of class I give the students what I like to call my “warning against trigger warnings.” It goes something like this:

“I don’t believe in trigger warnings. But if I did, I would have to include one for virtually every day of this course. We are going to cover subjects like slavery, segregation, sexism, suicide, the death penalty, and abortion. There is no way to teach this course without discussing these issues. And there is no good way to cover them without also considering a wide range of views about these subjects and their relationship to the Constitution.”

This WaPo article was my first unfortunate introduction to this story today. I’m curious why Justin chose to cast it contra the WaPo article as a defense of, rather than an attack on the practice of providing these warnings in classrooms. Did I miss something?

So when a Hispanic student gets up to give a class presentation, and the conservative students at the back start screaming “Trump! Trump! Trump!” or “Citizens Only!” the student has to take it? That’s the robust free speech Chicago protects?

These kinds of attacks have already happened to students and student athletes, as you know. This supposed concern about “coddling” and trigger warnings is really just to maintain the ability of conservative students to harass minorities and women.

In what classroom anywhere would that sort of behavior be allowed? Nobody is advocating allowing that sort of thing.

Hi Hey Nonny Mouse. Thank you for your comment. Of course none of us bien pensants here on DN would think such a thing is possible or, as you say, “advocate” for it. And I urge you to read the document plainly, asking yourself what incentives & excuses it creates for those who would – and will abuse it – and what protection or the lack thereof it offers. Search google and you will find such abuse is already happening at other conservative universities. Best wishes to you! .

Here’s my real take on this letter: it’s advertising.

It’s a signal to largely non-academic donors, in muted Trumpian machismo, that the University of Chicago isn’t going to put up with that crazy stuff that they keep hearing is happening in the rest of academia. Of course, it’s advertising in the same vein as Lucky Strike’s “It’s Toasted” campaign (from Mad Men), as no universities require trigger or content warnings, no universities aim to shield their students “from ideas and perspectives at odds with their own” (with the possible exception of some religious schools), and pretty much every university holds that its members “must have the freedom to espouse and explore a wide range of ideas.” So it’s bullshit, but it’s smart bullshit, and it will certainly generate revenue for the school.

Though I largely agree with the spirit of your comment, I find myself disagreeing with “no universities aim to shield their students “from ideas and perspectives at odds with their own””.

Here you can find a list of occasions where speakers were disinvited by a university (add filters “disinvitation? yes” and “event is not commencement” for more accurate/pertinent results):

https://www.thefire.org/resources/disinvitation-database/#home/?view_2_page=1

Michael Moore was actually disinvited by George Mason University and Cal State San Marcos. Also on the list of disinvitations were Ben Shapiro and Henry Kissinger.

I’m not all that fond of any of the above mentioned individuals (although, I do commend Michael Moore in some sense for his documentaries which, I think, were overall positive), but I do find it of interest that polemical political voices are being disinvited from university-sponsored speaking engagements. While it might not be in universities’ mission statements, there are some that seem to be in practice shielding students from certain perspectives.

On a less important note, stand-up comedians are also increasingly shunning university campuses; an article quoting Chris Rock on the topic: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/12/01/chris-rock-colleges-conservative_n_6250308.html

See Sergio’s (7:57) comment above re: the difference between shielding students from an opinion and not honouring someone who has that opinion. It might be a good idea to read David Duke in a class on racism, but it’s quite another matter whether it’s ok for him to be a commencement speaker.

I played around with adding filters a bit, but IIRC all three of the people I named were originally invited not for commencement speeches, but for some sort of campus debate or otherwise academically oriented speech (the site makes a distinction between commencement speech disinvitations and other types of speech invitations that were rescinded and has corresponding filters.)

While I agree with Sergio that we ought not honor people like GWB and David Duke with commencement speech invitations, is disinviting them from campus debates or otherwise academically oriented speeches akin to barring controversial yet topical readings from a class? I’m not totally sure, but it seems like if there’s a distinction between those two scenarios it’s a bit of a fine line.

I misread the *not* invited for commencement part of what you wrote, so fair enough.

Nevertheless, it strikes me that there is still a profound difference between being exposed to repugnant ideas in class and inviting people who espouse those ideas onto campus, since this does more than merely expose students to their ideas. In addition, it can express a degree of sympathy with them or the judgment that they make a valuable contribution to public debate in a democratic society (even if they are incorrect) and this judgment can in turn presuppose all sorts of other objectionable views.

Now perhaps we ought to err on the Millian side and have the David Dukes, Ickes, and Irvings of the world round for brown bag lunches every so often, and not worry too much about what message that might send to the overly sensitive. Whatever the case there, it would still not follow that the initial objection to their presence on campus is grounded in a desire to “shield students from ideas and perspectives at odds with their own,” which is precisely the point Justin was making. Instead, it would be grounded in the desire not to suggest that maybe those crafty Jews really were making up that whole Zyklon B palaver, etc. We don’t just live in the marketplace of ideas, even on campus, and not every question worth thinking about in class is an open question in society.

“Nevertheless, it strikes me that there is still a profound difference between being exposed to repugnant ideas in class and inviting people who espouse those ideas onto campus, since this does more than merely expose students to their ideas.”

To your point, equating the mere disinvitation of a speaker due to student protest with censorship is just down right disingenuous. That is not anywhere close to the adoption of an active policy by an institutional authority prohibiting the airing of the speaker’s views on campus in general.

I agree that universities ought not invite speakers who are downright inflammatory for the reasons you’ve mentioned.

However, I think that the possibility remains open for universities to be shielding students from ideas and perspectives. Take Michael Moore for example: he might be a bit fiery and obnoxious at times, but none of his ideas are themselves inflammatory. Yet he was disinvited from two universities all the same.

Since none of his ideas are grossly offensive, I can only imagine the universities rescinded his speaking invitations for political reasons. Whether their motive or desire was in fact to “shield students” from his ideas or not, it is effectively what they’ve done.

Well if it’s just the effect on what they’re exposed to that’s in question, then we in effect shield our students from everything that’s not on the syllabus. In which case:

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

The point about stand-up comedians doesn’t seem to be a free speech issue at all–at least not on the reading of free speech that underlies the University of Chicago letter. It’s not as though the colleges are banning the comedians from coming; from what Rock says it sounds like when comedians go to campus they gets a chilly reception, or maybe people protest them or something. Or perhaps people criticize their act on social media and it becomes a big headache.*

But those are all exercises of free speech! If comedians aren’t coming to campuses because they don’t want to deal with the criticism they get there–if, as Rock says, it’s not “fun” anymore–then that’s not anyone “shielding” the students from their perspectives, that’s them choosing not to bring their perspectives to campus.

Unless–unless–we want to say that members of the university community ought not to deliver such withering attacks on controversial speech that the people giving it feel uncomfortable making it on campus. That the university community should try to create on at least part of their campus a space that is, whatchamacallit, safe for such speech. This is defensible, though there’s some question about where the lines should be drawn about certain issues. But then, you know, we’re just negotiating about where the safe spaces should be and who gets them.

*I mean, this exchange, which immediately follows the discussion about campus talks. Bold-faced comments from Frank Rich, italics from Rock:

A few days ago I was talking with Patton Oswalt, and he was exercised about the new reality that any comedian who is trying out material that’s a little out there can be fucked by someone who blasts it on Twitter or a social network.

I know Dave Chappelle bans everybody’s phone when he plays a club. I haven’t gone that far, but I may have to, to get an act together for a tour.

Does it force you into some sort of self-censorship?

It does. I swear I just had a conversation with the people at the Comedy Cellar about how we can make cell phones into cigarettes. If you would have told me years ago that they were going to get rid of smoking in comedy clubs, I would have thought you were crazy.

It is scary, because the thing about comedians is that you’re the only ones who practice in front of a crowd. Prince doesn’t run a demo on the radio. But in stand-up, the demo gets out. There are a few guys good enough to write a perfect act and get onstage, but everybody else workshops it and workshops it, and it can get real messy. It can get downright offensive. Before everyone had a recording device and was wired like fucking Sammy the Bull,4 you’d say something that went too far, and you’d go, “Oh, I went too far,” and you would just brush it off. But if you think you don’t have room to make mistakes, it’s going to lead to safer, gooier stand-up. You can’t think the thoughts you want to think if you think you’re being watched.

Now the thing about this for me is, I agree that Twitter-mobbing can be deleterious to free speech (and to people’s civil rights in general), even if every individual act of it is the sort of thing that might fall under the notion of free speech. That’s the respect in which I don’t necessarily agree with the reading of free speech that I take to be at work in the U of C letter. But again, if you’re concerned about this, you’re concerned about creating a safe space from harassment for those comedians, and the same concerns apply to creating safe spaces for harassment for women and people of color and other people who catch much more harassment on Twitter than controversial comedians.

Also, the specific example that inspired the discussion involved a commencement address–and also Bill Maher, who isn’t just “edgy” but is an outright Islamophobe.

I should’ve made it more clear that the comedian tidbit was more of an aside than anything else.

But to speak to your comment, I very much agree that we ought to be concerned with protecting students from harassment. For example, I very much think we can (and should) do without those heinous preachers that show up outside student unions and spew hate speech and eternal damnations at passing students. Those guys are just assholes (if your campus is fortunate enough not to have these, look up Penn State’s “Willard preacher” for an example).

But I think we ought to consider things on a case-by-case basis. Rush Limbaugh probably shouldn’t be invited because he’s an obnoxious, inflammatory asshole. As far as comedians go, Michael Richards (aka Kramer) probably shouldn’t be invited. But is Chris Rock’s comedy really so egregious that students are in the right to flame him? He makes use of comedic license, certainly, but are students who would feverishly publicly berate him (or object to/try to prevent his appearance) getting a little carried away?

While I don’t think we ought to bring people onto campuses who are just going to be rude, racist, bigoted, etc, I think we have to be careful with disallowing or disinviting people who have ideas which we staunchly disagree with, though are capable of presenting them in a respectful way*. Generally speaking, I’m all for letting people with bad arguments get publicly ripped apart in a debate, especially if their arguments have underlying tones of racism, bigotry, misogyny, etc.

*Within reason. There are some things that I think we can all agree are just indisputably closed cases. E.g., I don’t think we should allow someone to come onto campus to speak out against marriage equality or argue that apartheid should be reinstated, no matter how “respectfully” they attempt to do so. While I’m generally not one to attempt to articulate *exactly* where a line ought to be drawn, I think that we can reason about these things without getting too carried away in either direction.

“But is Chris Rock’s comedy really so egregious that students are in the right to flame him? He makes use of comedic license, certainly, but are students who would feverishly publicly berate him (or object to/try to prevent his appearance) getting a little carried away?

“While I don’t think we ought to bring people onto campuses who are just going to be rude, racist, bigoted, etc, I think we have to be careful with disallowing or disinviting people who have ideas which we staunchly disagree with, though are capable of presenting them in a respectful way*.”

Well, this kind of makes my point about the conflation of criticism and suppression. Are students right to flame Chris Rock? Maybe, maybe not, depends on the specifics of the case.** Should the university try to stop the students from flaming Chris Rock? Absolutely not–this would be more of a violation of free speech on campus than anything we’ve discussed. Even if students are interrupting Chris Rock, the norms of interrupting standup comics are different than with other speakers. Should students try to prevent Chris Rock from being invited to campus? Probably not (unless it’s the student government doing it or something, in which case the students should have a direct voice). Have any students tried to disinvite or disallow Chris Rock? Not as far as I can tell–he said he stopped performing on campuses of his own free will because it wasn’t “as much fun as it used to be.”

Anyway, granted this is all an aside, I do think in the general case those who think of themselves as defending academic freedom against safe spaces are often conflating these two things. If you look up Wendy Kaminer’s complaints about the reactions to her appearance at Smith College, those reactions are entirely within the bounds of free speech. It comes across as though Kaminer wanted a safe space to say the n-word (and get the audience to say it) and insist that the campus newspaper reprint it by saying, well, the n-word rather than “[n-word].” And again, if people have an absolute right to free speech, then other people have an absolute right to criticize them. That’s not to say that the sort of movements that Ellison is attacking (or that are in the area of his straw target) don’t suppress speech on some occasions, but it seems to happen a lot less often than it’s portrayed as happening.

Also, that twitter stream that Kathryn Pogin linked is illuminating–it’s not obvious that the U of C’s commitment to free inquiry extends to questioning administration policies.

**Since he doesn’t mention any specific incidents it’s hard to tell exactly what set him off. But one possible reason that playing colleges “is not as much fun as it used to be” could be that, as you slide into middle age (like me), maybe your material doesn’t connect as much with college students as it did when you were younger and, well, more cutting-edge? Though in all modesty, last semester I had a SpongeBob joke that absolutely killed.

FWIW, the former student body president agrees with Justin that this was essentially advertising: https://mobile.twitter.com/tylerbkissinger/status/768938663120109570

Justin,

Describing the mission of a school is no more a “trigger warning” than describing the mission of a brothel is a come on. If people do not know what an establishment is about, people will not be able to make informed decisions about frequenting the establishment.

I have no issue with letting incoming students that college will challenge their beliefs and may offend them due to that. I taught courses in which I chose issues and topics because they were controversial. However, I explained this to students the first day of class, told them the issues, and said that if even considering the options on the issue would bother them they needed to decide if they could participate in discussions or not. If not, maybe considering a different class was appropriate. I never had a single student leave the class. I think the key is that individual professors make it clear that the point of some college classes is to challenge preconceived notions, not to change them, but to get the student to look at them critically and become able to defend their views better, or if having been challenged and finding their views to be unsupported, change them. I presented the issues as objectively as possible, presenting both sides and letting students express their views and debate them, always with the understanding that debating uncomfortable issues was what college ought to do. Why? because the cold, cruel world was not going to coddle them.

And that’s my one worry. As I said, I have no problem and did warn students that they might be offended when we challenged their beliefs. However, I do fear that the camel’s nose in the tent — of warning them — will lead to censoring what individual professors can present and debate if it will offend students. I see no issue with offending students if it gets them to think critically and finding a way to defend their beliefs — it is motivation, after all. So, bottom line, I have no problem with the warnings, used such myself for 35 years, but hope it does not lead to restrictions on what colleges allow professors to address. There is nothing to be gained by not challenging everyone’s beliefs in the spirit of rational debate and inquiry.