Are History’s “Greatest Philosophers” All That Great? (guest post by Gregory Lewis)

“Why are the greatest philosophers skewed towards the past, when they should be skewed towards the present?”

The following is a guest post* by Gregory Lewis, a medical doctor and amateur philosopher, in which he looks through a statistical lens at the formation of the Western philosophical canon.

You can read more of his writings, including an earlier version of the piece that follows, at his site.

Are History’s “Greatest Philosophers” All That Great?

by Gregory Lewis

Introduction

In the canon of western philosophy, generally those regarded as the ‘greatest’ philosophers tend to live far in the past. Consider this example from an informal poll:

- Plato (428-348 BCE)

- Aristotle (384-322 BCE)

- Kant (1724-1804)

- Hume (1711-1776)

- Descartes (1596-1650)

- Socrates (469-399 BCE)

- Wittgenstein (1889-1951)

- Locke (1632-1704)

- Frege (1848-1925)

- Aquinas (1225-1274)

(source: LeiterReports)

I take this as fairly representative of consensus opinion—one might argue about some figures versus those left out, or the precise ordering, but most would think (e.g.) Plato and Aristotle should be there, and near the top. All are dead, and only two were alive during the 20th century.

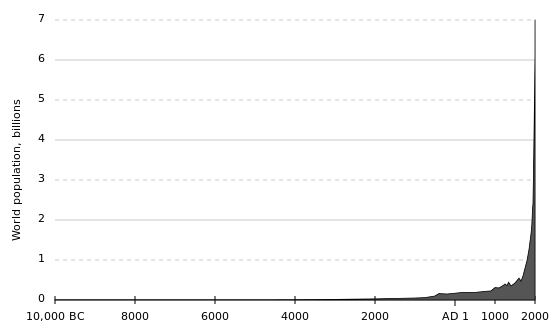

But now consider this graph of human population over time (US Census Bureau, via Wikipedia):

The world population at 500BCE is estimated to have been 100 million; in the year 2000, it was 6.1 billion, over sixty times greater. Thus if we randomly selected people from those born since the ‘start’ of western philosophy, they would generally be born close to the present day. Yet when it comes to ‘greatest philosophers’, they were generally born much further in the past than one would expect by chance.

Where are the 13 Platos in modern day Attica?

Consider this toy example. Let’s pretend that philosophical greatness is a function of philosophical ability, and let’s pretend that philosophical ability is wholly innate. Thus you’d expect philosophical greatness to be a natural lottery, and the greatest philosophers ever to be those fortunate enough to be born with the greatest philosophical ability.

The Attican population in the time of Plato is thought to have been 250 to 300 thousand people (most of whom weren’t citizens, but ignore that for now). The population of modern day Attica (admittedly slightly larger geographically than Attica in the time of Plato) is 3.8 million. If we say Plato was the most philosophically able in Attica, that ‘only’ puts him at the 1 in 300,000 level. Modern Attica should expect to have around thirteen people at this level, and of this group it is statistically unlikely that Plato would be better than all of them. I am sure there are many very able philosophers in modern day Athens, but none enjoy the renown of Plato; were Plato alive today, instead of be recognized as one of the greatest of all time, perhaps he would be struggling to get tenure instead.

This example turns on how one defines the comparison classes, and these are open to dispute (e.g. was Plato the best in Attica, the best in Greece, or the best in the ancient world?) But the underlying point stands: If philosophical greatness were a matter of natural lottery, the most extreme values of a much larger population are usually greater than that of a much smaller population, and the distribution of greatest philosophers should be uniform by birth rank. It would be incredibly surprising that three of the top ten greatest philosophers of all time (Plato, Aristotle, Socrates) would be situated in such a small fraction of this population.

Why doesn’t Athens now have more than 13 Platos?

The toy example is grossly simplistic, and many factors intervene between being naturally gifted at philosophy and one’s ‘mature’ philosophical ability. Yet this makes the ‘pastward skew’ of philosophical greatness more surprising, not less. Modern society seems to be replete with advantages compared to Plato’s time which should make it better able to nurture the naturally gifted into great philosophers. I list a few of the most salient below:

- No matter how gifted, it is hard to become a great philosopher if you die in childhood. We don’t know for sure the infant mortality in ancient Greece, but it is almost certainly at least an order of magnitude greater than the present day.

- Even if one doesn’t die, one can become stunted or cognitively impaired due to insults in childhood or early life. Again, we don’t know how prevalent this was, but it certainly it is much less now than then.

- Although there remain lamentable barriers to people who aren’t rich white men entering philosophy in the present day, these were even worse in the past: compare ones prospects as a woman in modern Greece versus ancient Athens, or as someone from a lower socioeconomic group versus a slave.

- As the world is now richer and safer, budding philosophers have a much greater chance of being able to devote their time to philosophical training and understanding, instead of being trapped in subsistence farming or political intrigue.

- Insofar as philosophy is a constructive endeavour on prior work, we have the benefit of 2000 years of subsequent philosophy that Plato could never access.

- Insofar as philosophical understanding can be informed by other fields (e.g. natural science, linguistics), the much greater development of these now are also advantages.

- Technology allows us to have much wider and easier access to our peers and philosophical work.

And so on. By contrast, it is difficult to think of many factors which favor Plato’s time versus our own—they are shaky as pro tanto considerations, and seem unlikely to be similarly weighty:

- One might suggest a ‘field dilution effect’. Skipping across fields, one may wonder whether if Shakespeare were alive today he might be producing films or TV rather than plays. Similarly, there has been a proliferation of fields in academia, and people who would have been philosophers in an earlier time might in the modern day work in a different field.

- One may suppose a network effect – maybe being in close collaboration with other great people enhances the greatness of one’s own output. This would suggest clustering, but more would be needed to explain why clusters should happen more often in the past – perhaps some elements of an elitist or ‘aristocratic’ education was better at developing extremely highly levels of performance.

- There could be an assortment of ‘decline of the world’ (or at least ‘decline of the west’) explanations: maybe certain important cultural or political values have deteriorated to the detriment of our ability to think well, or (more locally) the field of western philosophy has derailed and so produces less value per unit of human capital invested.

If on balance these factors favor the present over the past, why are the greatest philosophers skewed towards the past, when they should be skewed towards the present?

The benefits of being good in the past

I suggest a better explanation of why the greatest tend to be ancient lies in how we perceive philosophical work. Even though Plato may not have been as ‘naturally’ able as the best philosophers today, and labored under several disadvantages for developing his philosophical ability, being born in the distant past gave him several advantages for his posthumous reputation.

First is low-hanging fruit. In fields like science and mathematics, one may suggest it is easier to make earlier breakthroughs versus subsequent ones: with a high school education I can solve some basic problems in Newtonian mechanics—I can’t do any ‘basic’ problems in general relativity without many years more study, and I may not be clever enough even then. Whether philosophy makes ‘progress’ in a similar way is controversial, but insofar as it does being born early with more (and relatively easier) ‘great breakthroughs’ have yet to be made is an advantage.

Second, related to the first, a mix of polymath premium and forefather effect. Given the relatively primitive and unexplored state of the field of philosophy in antiquity, there are lower heights to scale to reach the limit of human knowledge, and one can stake ones claim to much wider expanses of ground. A.N. Whitehead famously called western philosophy ‘footnotes to Plato’: this may depict Plato as a titanic genius, but may instead be driven by his being fortunate enough to live at a time where he could be the first to sweep across so much, and thus leave his successors relatively more incremental advances to make.

Third, and also related, is retroactive esteem. If one writes the locus classicus for a topic (or an entire field), this gets one a lot of exposure, and a lot of esteem. Even though modern day Aristotelian ethics goes much further than Aristotle ever did, that it all refers to his work gives him an almost mythic quality.

Does it matter if the Ancient Greats weren’t that good?

Does this matter? That ‘historical luck’ as opposed to (forgive me) some Platonic ideal of philosophical genius may have had more to do with Plato’s perceived ‘greatness’ doesn’t mean we shouldn’t regard him as a great philosopher, or Euthrythro or The Republic as great works of the western philosophical tradition. That it may be plausible that Aristotle born in modern times may not be capable of understanding, let alone contributing to the modern state of the art of Logic does not make the seminal early contributions he in fact made any less important.

But it perhaps should make us less deferential towards the ancient greats. Instead of a large secondary literature to find a good argument in Socrates’s infamous refutation of Thrasymachus near the start of The Republic, we should be more willing to believe that Socrates/Plato just made a bum argument: they were not that brilliant, and so the chances of them doing some bad philosophy is not that low. Further, if we don’t believe they are singular geniuses in human history, study of their work should be principally of historical interest: in the same way modern students of physics read contemporary introductions rather than Einstein’s original papers to understand relativity (still less process through the primary works leading up to Einstein), students who want to understand the subject matter of philosophy are better served if they make the same shortcut with modern introductions to the field and read only contemporary primary literature; similarly, we should expect the scholarship of Plato or Aristotle (or any ‘great philosopher’) to improve our understanding into the history of ideas, but not to excavate some hidden philosophical insight relevant to modern discussions.

This is also an optimistic iconoclasm. If I am right, philosophy now is vastly richer than classical Greece, the age of reason, or any other golden age we care to name: far more (and more able) philosophers with much greater ability to collaborate and learn from one another, a wider understanding of the world around us, a long history of our predecessors who have cleared the way before us, and much else besides. Many, perhaps most, universities boast a philosophy department that puts the Lyceum or the Academy to shame. Although our chances of becoming a ‘great philosopher’ have fallen, our chances of getting to the truth have risen. If Plato could have traded the former for the latter, he would have done so joyously.

(image: fresco from The Tomb of the Diver, c.475 BC)

Interesting post.

One consideration I didn’t see, but may have just missed: the effect of overspecialization. Philosophical greats tend to have grand visions. It’s hard to have a grand vision, let alone a good or interesting one, when your work is the philosophical equivalent of a sub-sub-subreddit. This hypothesis is a version of the low-hanging fruit hypothesis, but one where the fruit is a stand-in for grand visions.

I am puzzled. Lewis says that the “primitive and unexplored” state of philosophy in Plato’s time made him “fortunate”, as “he could be the first to sweep across so much”. But isn’t this rather — or at least also — Plato’s MISfortune, since it meant that he had to work as a philosopher mostly from the ground up? (I can make progress in philosophy by reading Plato and footnoting him, whereas Plato got to footnote … Parmenides.) And then isn’t the fact that Plato’s ideas were so intrinsically brilliant (and sorry, if you deny this I will FIGHT YOU) all the more amazing because of this?

If we take as a given that Plato was intrinsically brilliant (so as not to provoke a fight with you 🙂 ), I think Lewis’ point still holds. Someone as intrinsically brilliant would have a harder time sticking out if the path had already been paved. Law of increasing marginal costs, you know…

These comments seem to forget that Plato, and Aristotle and others of that time, were writing at a time they considered the end of a long tradition. They were looking back as well as philosophizing.

it also seems people forget that topics they discussed were/are relevant to the most basic experience of human consciousness. In my earlier comment below, I mentioned Plato’s text “Theatetus” which (in case anyone forgot) elaborates his theory of knowledge. It is relevant today, in fact his description of how the brain imprints knowledge is surprisingly close to the most modern theories.

Philosophers can and should be judged on how they impact society. (What else are they good for?) There is no doubt that Plato, Aristotle especially, as well as other ancient Greeks heavily influenced Western civilization.

I’ve listened and considered what you have written. I can surely draw one conclusion. Plato certainly was MISfortunate not to have had his philosophy served to him on a silver *plato.

* Typo — Typing is not my first, second, or even third language.

Plato was a student of Socrates. He hardly started from scratch 🙂

This article asks whether the ‘great’ philosophers were really that great. And it seems to answer, “Yes, but…” But this seems like exactly what we all hear from philosophy professors when we take philosophy classes, so I’m a bit confused as to where the iconoclasm comes in. We praise the genius of the greats, but no one (or very few) attempt(s) to perpetuate the mythical greatness that the article seems to take as its target. Or is the article’s target meant to be the mythical greatness that is perpetuated by names like ‘Plato’, ‘Socrates’, ‘Descartes’ being used as shorthand for whole lineages of ideas that have had enormous influence? If so, that also doesn’t seem iconoclastic either.

The list of great philosophers is interesting, How many of them were in philosophy departments?

The right question is how many of them did study philosophy at a university, and the answer is “most of them”. This is what philosophy departments are for.

Does it make a difference if we consider the members of the above philosophical pantheon to be (historically) significant rather than great?

Yes, because ‘greatness’ implies ahistorical objective superiority, which is a damaging construct that excludes and perhaps even silences people working with different conventions or in different contexts. ‘Historically significant’ is preferable because it acknowledges that we are working within a culturally embedded tradition.

Maybe so, but that seems to depend (i) on whether there is objectively better and worse philosophy and (ii) on whether said exclusion or silencing can be avoided by an alert group of philosophers.

Presumably there is a fact of the matter about whether, say, Hume was a great philosopher. It’d be shocking if Hume alive today would be just mediocre by our standards. He was great because he would stand out as great in any tradition. None of this denies that intellectual/philosophical traditions shape and are shaped by their cultures.

The art of exegesis is, in large measure, the art of reading coherence into the incoherent views of these guys (and I do mean “guys”).

Suppose, as seems plausible, that it takes a decent amount of time to sort out who was a really great philosopher and who just appealed to people of his or her time. If that were so, we should not expect to be able to name the greats of today even if there are proportionately as many today as there were in Plato’s day. Additionally, surely great philosophers do not tend to spring up out of nowhere but emerge from a great philosophical environment. Equally talented philosophers will produce less good stuff if not surrounded with people who can help them develop their ideas.

I think this is exactly right. One of the reasons I am so confident that Aristotle and Plato were great philosophers (and I don’t even work in history of philosophy) is because their work has remained important and still resonates after such a long time. Of course, the quality of their work may only be one of a number of reasons for that longevity, but I think it’s an important reason nonetheless.

Readers might be interested in a related post from earlier in the year: http://dailynous.com/2016/02/24/is-this-the-golden-age-of-philosophy/

A fascinating topic. The post seems to ask some important questions. But what an odd list of philosophers. This reader’s top ten would not include any of these names mentioned except perhaps Aristotle. I struggle to think of what Plato did other than confuse the issues and start an Academy, and as for Witt…. But okay, each to his own.

—-“A.N. Whitehead famously called western philosophy ‘footnotes to Plato’: this may depict Plato as a titanic genius, but may instead be driven by his being fortunate enough to live at a time where he could be the first to sweep across so much, and thus leave his successors relatively more incremental advances to make.”

It seem unlikely to me that Whitehead meant to imply Plato’s genius. What sort of genius solves no problems? Some would say that Whitehead easily outperforms Plato and shows us how to avoid writing footnotes and I suspect that Whitehead thought this. He complains that commonplace folk-Christianity is a religion ‘in search of a metaphysic’ and Plato did no better.

—“If I am right, philosophy now is vastly richer than classical Greece, the age of reason, or any other golden age we care to name:”

This seems true. But have we really been through two or more ‘golden ages’ and yet still not moved on? How many more golden ages will some signs of progress require? I feel any golden age must be in the future if it is anywhere. The age of reason? We have passed through it unscathed and still write footnotes to philosophers who pre-dated it. Let us look forward to a golden age of philosophy and work towards it, not imagine that we can go through a golden age and end up back where we started. This idea does not seem to make sense.

It is wonderful that DN raises these topics for open discussion, and it certainly does seem that the internet might eventually lead to a golden age.

“What sort of genius solves no problems?”

Seriously???

I take issue with the idea that Plato didn’t solve any problems. On some of the more interesting readings of Plato, he solved the problem of how to force his readers to deal with and engage certain ideas and arguments without simply pontificating on the ways he saw things as the rhetoricians did. He did so by writing in dialogues (magnificently rich and complex literary dialogues at that).

But let’s set that aside for a moment and accept that Plato didn’t solve any real problems. Under the contemporary philosophical conception of what it means to solve a problem, this is perhaps true (whether that says more about Plato or contemporary philosophy is another question).

Does one really have to solve problems to be a genius though? If we accept that Plato didn’t solve any problems, then surely Shakespeare, Beethoven, Caravaggio, Woolf, and Tarkovsky didn’t solve any problems either. And if THEY aren’t geniuses, then I’m not sure who is. Perhaps that’s your point, but I’ll hold onto the idea of genius until my last breath.

I really think that any sort of equation between problem solving and genius is about as narrow minded and reductive as it gets. So if Plato doesn’t qualify under this criteria, then I say all the better for him.

A top ten in philosophy that excludes Kant, Plato, Descartes, et al (with the possible exception of Frege) is odd. Who in the heck would you include?? And is the list a product of a bias toward one branch, school or era of philosophy??

Hello DocFEmeritus

I might not exclude Kant and would happily include Socrates if we knew more about him, but a list of ten doesn’t leave much room for choice. Offhand, and this list could be much improved and lengthened considerably with more thought,, I’d consider a place for Nagarjuna. Avicenna, Rhadhakrishan, Schrodinger, Weyl, Spencer Brown, Bradley, Plotinus, Balsekar and many others ahead of those that are currently on the list,. The list would favour not an era or a branch but thinkers who proposed solutions and showed us a way forward. On reflection I;d probably include Kant for his recognition and formulation of the problem that needs to be solved, and for his insight into scholastic metaphysics as an ‘arena for mock fights’. But with only ten to play with he might just drop off the bottom.

Hi Incredulous

You seem to have read my words is a rather odd way.

You clearly agree that Plato solved no philosophical problems, or at least cannot cite an example,. The other people you mention are not (officially) philosophers so are not relevant here, (although I’d rate Shakespeare very highly.) They all solved the problems they needed to solve.

Genius comes in many forms and would not require the ability to solve a philosophical problem,. But to be considered a genius as a philosopher would seem to require exactly this. No great composer has been unable to solve the musical problems they faced. .

You say – ‘Under the contemporary philosophical conception of what it means to solve a problem, this is perhaps true’

I had no idea that there could be more than one meaning for the phrase ‘solve a problem’, The meaning does not seem to have changed sine Plato’s day but I’ll stand by my comment even if it has. .

The first step in solving a problem would be facing up to it. I feel that you are endorsing the common practice of sweeping it under the carpet. I wish to fight for the value of philosophy and see it taught properly in schools and made more accessible generally, but this would be out of the question while it has such low self-esteem that it questions the possibility of anyone ever solving its problems. It becomes unsaleable at any price.

Plato did not have problems to solve, because the problem -> theory -> solution mechanic which is now so widely employed to great use by philosophers was not a formal methodology in Plato’s time. If he used the word, would not be using it in the same way as you do. Of course the Republic, for example, contains numerous examples of what looks like this mechanic in an extended and deep engagement with Plato’s subject matter. In fact a huge portion of Plato’s influence and supposed greatness is due to his discussing philosophy with something like our modern methodology so deeply and over such an extended set of arguments. Without his work, our modern methodology does not appear in the form in which we currently perceive it, even if another philosopher has replaced Plato, there is nothing to say that the results thousands of years on would have been recognisable as modern philosophy to us.

Well, I think there’s a category error here: namely, the job of philosophy is to tackle and solve problems or issues. The job of music, plays, painting, etc… is not to solve problems, except in an artistic sort of way. This is sort of like saying the task of physicists like Einstein or Bohr, or medical researchers such as Pasteur, is not to solve problems. If only problem solving were the mark of genius, then yes, I’d agree, but it surely is part of the genius of philosophers. Imagine a philosopher who never settled or tackled an issue in order to solve it…that would be which philosopher??

Again, I did not suggest that solving problems is necessary to establish the presence of genius. We were talking about philosophers. All the same, the job of a composer, as I like to consider myself, would be exactly to solve problems, albeit not only that, and many composers set themselves problems to solve as a way of inspiring the music. Try writing production music and not seeing it a problem-solving exercise! Even just harmonising a chorale tune could be seen as a technical problem to be solved. Philosophy must be alone among all academic disciplines in not seeing problem-solving a part of its job. On this issue I’d be with Dawkins and Krauss.

Do you really believe it is a category error to imagine that a philosophers job is to solve problems? This is where I struggle to understand a certain view of philosophy. What other reason could a philosopher have for existing? It never occurred to me when I took it up that there was any other reason for doing it and I feel the same now. What I see is a hidden assumption that these problems cannot be solved, and this is what i will always fight against in case it gets passed on to students. It is a view that depends on excluding a great many philosophers from the top ten list.

My point was simple. No mathematician who never solved a problem is considered great – afaik. So what makes philosophers any different?

You asked – ”Imagine a philosopher who never settled or tackled an issue in order to solve it…that would be which philosopher??

I’m afraid I don’t understand the question. If a person has never settled or tackled an issue then they have not solved it and are not even trying to do so. I think I’m reading it wrongly but am not sure in what way.

.

Why do you think philosophy is about solving problems rather than, say, figuring out what the insolvable problems are and showing us better and worse ways to think about them? Solving problems is for engineers, not philosophers.

At the risk of excessive self-promotion, readers interested in this line of thought might be interested in my discussion in “Contemporary Metaphysicians and Their Traditions” Philosophical Topics (2007) 35: 1&2: 1-18, especially pp 11-16, where I argue that even though we should expect many of the best philosophical works until now to have been written in the recent past, there is still an important range of reasons for engaging with the history of philosophy. (The focus of the paper is on metaphysics rather than all of philosophy, but the discussion should generalise – if anything, we might expect more directly empirically informed philosophy to be even more superior to past philosophy.)

The best way to find either the published version or a pre-publication draft is through Philpapers: http://philpapers.org/rec/NOLCMA

I am familiar with your work, Professor Nolan, and have always found it most interesting and rewarding. Thank you for the link!

Daniel – I would like to read it but it’s behind a paywall.

The unpaywalled draft is available here:

https://sites.google.com/site/professordanielnolan/home/files/NolanContMeta.pdf

The final version is also on JSTOR, which allows downloads for free for people who register.

Okay. Thanks. I’ll get to it later.

Daniel – Thanks. Enjoyed it.. I;d make a comment or two but can’t do it here.

I very strongly agree with this bit:

” in the same way modern students of physics read contemporary introductions rather than Einstein’s original papers to understand relativity (still less process through the primary works leading up to Einstein), students who want to understand the subject matter of philosophy are better served if they make the same shortcut with modern introductions to the field and read only contemporary primary literature”

Philosophy, especially at undergrad level, should NOT primarily be about studying classic works of the great dead.

I also strongly agree with this bit:

“we should be more willing to believe that Socrates/Plato just made a bum argument: they were not that brilliant, and so the chances of them doing some bad philosophy is not that low.”

Too much history of philosophy bends over backwards to find charitable readings of old philosophers as free from error. This may have some benefit as a way of producing ingenious new distinctions etc, but it is also makes philosophy look really bad when so much effort is spent in producing endless ‘talmudic’ readings of a sacred cannon which is treated as immune from error . . .

Wow, the whig history to end all whig histories (index “great” to us and, yes, we look pretty great). Embarrassing.

“Even though Plato may not have been as ‘naturally’ able as the best philosophers today…” All one can say is….hmm.

My eyes apparently refused even to process that one. Instead they flitted briefly past mention of the “Euthrythro” and settled upon, “may be plausible that Aristotle born in modern times may not be capable of understanding, let alone contributing to the modern state of the art of Logic.”

Hmm.

I think there’s a great deal to commend about this piece; certainly it’s absurd to suppose that Plato, Aristotle, or Socrates (who as an individual we are almost entirely ignorant of!) were smarter or somehow more gifted than contemporary scholars, who have, after all, the benefit of thousands of years of thought on these issues, and I’m sympathetic to the idea that forcing students to slog through Nicomachean Ethics, for example, is a bad way to introduce ethics in undergraduate survey courses. I want to focus on the last part of the piece though, from the perspective of someone who studies ancient philosophy as philosophy under the current analytic paradigm. Lewis suggests, as I read him, that scholars of ancient philosophy are wasting their time trying to figure out what’s going on in, to use his example, Republic I, and that in a passage like it we should simply cede Plato made a bad argument and move on. But certainly that the arguments in Republic I are bad has been suggested–a large part of the secondary literature is devoted to explaining the faults with the argument. But these faults are not self-evident, and one can intelligently think a different version of it is more faithful to the text and successful, and so we progressively gain understanding of how Plato’s arguments work and whether they are successful. Another part of the problem is that Plato is not responding to opponents of his views and writing a polemical piece in response–he is writing the arguments of Thrasymachus, as much as Socrates, so even if the arguments proposed by Socrates fail in Book I that may be part of Plato’s overall design. Even if this sounds like a cheat, it’s worthwhile to investigate and then see which hypothesis makes more sense of the text, that Plato mistakenly thinks a bad argument works or that the character Socrates is making a bad argument which Plato recognizes. The goal of this is in part to understand the original text, which is interesting in and of itself. This doesn’t require that we take Plato to be an incredible genius who never gets anything wrong, and about the same procedure is typical of any philosophical work in ancient philosophy–we make the best interpretations of the arguments in the texts possible, trying not to facilely dismiss the arguments contained, uncritically accept them, or substitute a good argument for the authentic one.

I don’t think any of this is incompatible with Lewis’s main claim, which I take to be that ancient Greek philosophy (and presumably the history of philosophy in general, unless the ancient Greeks are particularly dull) is not able “to excavate some hidden philosophical insight relevant to modern discussions.” But this seems to me entirely wrong, and not because the Greeks (or earlier philosophers in general) were a singularly brilliant people. What they do have is the benefit of not being raised in our cultural and intellectual milieu, which can lead to insights we have overlooked. The development of contemporary virtue ethics, for example, is directly influenced by rereadings of ancient ethics, and certain prominent figures in contemporary ethics (i.e. Julia Annas and Martha Nussbaum) are trained in the ancient tradition. The Theaetetus was invoked by Ryle and Wittgenstein in their discussions of logical atomism. Going a bit further back, the rediscovery of Sextus Empiricus’ work on Pyrrhonian skepticism was incredibly important to Hume. The phenomenon is of course not exclusive to ancient Greek philosophy; Schopenhauer as well as many contemporary philosophers are influenced by classical Buddhist and Indian philosophy. There are countless examples of thinkers either being directly inspired or finding their work anticipated in an earlier text. None of this was contingent on treating the ancient text in question as the Sacred Truth, but just reading someone who thought in a different, interesting way. This isn’t to deny that, to paraphrase Jonathan Barnes, most of ancient Greek philosophy isn’t dross. But the trouble is figuring out which parts of it are dross, and which are philosophically fruitful, and that seems to be purely philosophical work.

Hmm! So far as I can see this seems to be saying these Greeks weren’t all that great. Monty Python debunked that notion prett effectively as regards to the Romans and I dare say you could do the same either ancient Greeks. What have they ever done for us (except for philosophy, architecture, geometry, other maths I’m too stupid to understand, the writing of history, theatre etc etc). Yes I’m convinced, what a woeful bunch of thickoes.

This is really interesting stuff! However, I don’t think Greg shows that ‘we should be more willing to believe that Socrates/Plato just made a bum argument’, that ‘study of their work should be principally of historical interest’, or that ‘students who want to understand the subject matter of philosophy are better served if they make the same shortcut with modern introductions to the field and read only contemporary primary literature’

As far as I know, historians of philosophy are very often critical of the figures they study – I have never found an attitude of slavish devotion in their work. Nevertheless, approaching a text through the lenses of the principle of charity – instead of immediately throwing our arms up in the air and deciding Plato was just wrong – helps us (a) understand the text (because historical distance makes texts harder to get right on a first try) and (b) come up with interesting insights based on it. That such insights are available (Ancient Student’s post includes a few examples) shows that these works are not of mere historical interest. That idea seemingly depends on a picture of philosophy as a discipline where we accumulate knowledge and move on, which is, in my view, an implausible description (studying the history of philosophy shows to what extent the same questions emerge again and again).

As for what students should read, I’m all for letting a thousand flowers bloom! Different topics draw different students into philosophy. That said, I have found studying history of philosophy both intrinsically rewarding and very helpful when approaching contemporary debates, and think they are mutually enriching. The pictures drawn up in the classics keep emerging – dressed up in fancier terms and made more precise – in contemporary works, and it is often illuminating to have the more systematic, more condensed picture given in the classics in the background. In addition, studying history of philosophy encourages close (and critical!) textual reading, attention to the details of arguments, and drawing connections between different questions and thinkers – all crucial skills in (contemporary) philosophy.

For all that, I think we can take away a really positive message from Greg’s discussion: that we should treat contemporary texts with the same charitable spirit with which we treat the classics of philosophy, and that we should read philosophy done all over the world – taking into account the numbers, *only* reading philosophy written in North America and in Europe will also drastically reduce the talent pool we are drawing on.

Glad to see my “dark age of philosophy” comment being reaffirmed…

I love working on old cars and trucks. Everything is simple, straight forward, and I can take it apart piece by piece, fix it, and put it back together. Mechanically driven with a modest analog system in assistance is such a beauty thing in its simplicity. The analog diesel, spare the starter, alternator, and fuel shut off switch will run without analog support until the fuel is consumed.

Modern cars have 4 things in common with old cars, namely 4 tires.

Other than that everything on modern day vehicles (MDV) is controlled digitally. The mechanical workings in MDV can not function without the digital overlord providing preapproval. One tiny digital sensor no bigger than the average thumb that reads exhaust fumes composition goes haywire and it will shut that bright and shiny $50,000 dollar diesel pickup dead in its tracks.

Good luck figuring out which sensor.

The moral of the story as related to the OP is 3 fold.

1) Just because it’s dated, doesn’t mean it has lost its usefulness beyond a historical footnote.

2) The ramp up of modernization is not necessarily an improvement, and in fact more often than not a pain in the backside when things go sideways.

3) Philosophy is fun. If it made one consider the possibilities, options, and left a taste in the mouth that one hasn’t arrived yet, then it is alive and well. A success, and proof of its worthiness!

Cheers

My inner luddite applauds you.

?!?!

Plato wasn’t just the smartest guy in Attica. And he wasn’t just a guy who happened to have an exceptionally high IQ, as if anyone with a high or higher IQ is capable of what Plato did. He was highly creative in ways that outstrip any quantitative measure of genius or “capability”, and that are indexed to his historical and cultural situation. He basically created philosophy. So, no, there shouldn’t be 13 Platos in modern day Attica.

When I read this as a reductio of ahisorical and scientistic modes of philosophy, it reads much better. Could we be more tone-deaf when it comes to our own history?

There is not a single real concept in this piece, except the presupposed, scientistic, concept of philosophy as problem-solving. It is of a piece with the concept-blindness that characterises much of modern analytic philosophy. In cinematic terms it amounts to seeing THE MARTIAN as a greater fil than 2001 A SPACE ODYSSEY because the second film presents more problems than it solves.

Ok, let’s agree with you that Plato “wasn’t just the smartest guy in Attic” but was “highly creative in ways that outstrip any quantitative measure of genius.” The question remains: why were the “highly creative” people clustered in the past?

I don’t know, but my best guess is that sometimes, the cultures that shape our thoughts are vapid and stale, and that this is one of those times.

I agree with babygirl. There should be, by this article, 10 Mozarts, 12 Michelangelos, 13 Leonardos, 8 Einsteins and 25 Newtons. It’s completely silly. It is an interesting question as to why there are “golden ages” of sorts (Classical Athens, 1BCE-1CE Rome, Renaissance Italy, and so on – I am mostly familiar with European History, but the little I know of the rest of the world seems similar) in which certain disciplines or things get created in lasting and amazing ways. I guess part of it is that being the first or among the firsts – an origin. And perhaps that people come in pairs that somehow filter or motivate each other. Plato & Aristotle basically invented Western philosophy (well PLato did, Aristotle gave it two sides) – for all we know Chrysippus was smarter than they, but being smart is, by itself, meaningless (there are plenty smart but somehow amazingly dumb, uninsightful and unoriginal people). I often think of Lennon/McCartney (together – not apart). Sure, they were/are amazing, but it was also the place, the time, their own matching/opposed personalities and tastes.. Beatles is still here and probably will be long after most other greats are reduced to 2-3 songs. Not that they were the best musicians – I am sure Prince was a better one, for example.

The old greats are so mandatory to read because their work is a prerequisite for literacy in our field. In this way philosophy is weird. Physicists don’t read Newton’s Opticks, because their contemporary textbooks restate and improve on Newton’s own writing, rendering it dispensable. Philosophers simply never undertake to write a book whose aim is to distill everything of value in Kant, so that philosophers would henceforth be spared the burden of having to actually read the quirky original. One reason for this is that Kant (and many others) are a part of the hazing that marks various philosophical rites of passage. Another is inertia of a different sort: Educated philosophers are expected to be conversant in the greats, so we’d be remiss to leave them out of the curriculum. This inertia would operate even if this common disciplinary vocabulary, rooted in deep history, were far from the globally optimal one for the discipline. Third, philosophers have a bookish temperament that disposes them to like reading old books and the feeling of being viscerally engaged in millennia-spanning debates. Fourth, we don’t have enough confidence in our contemporary work to feel comfortable in “closing the book” on the old masters. We have no confidence that we’re able to even recognize what is valuable and what is dispensable in Aristotle, so every generation turns that question back to its students. Physicists don’t have that attitude about Newton or Einstein. They might read old papers for a semester if they are especially interested in feeling well rounded, but most never glance at a page from the primary sources. It’s not that they are ignorant of their field’s ancient history. They simply learn about it from contemporary, readable distillations. I don’t think that philosophy would break if we developed the same clear-eyed attitude about our past, so it’s interesting to think about why it seems so hard to picture.

This seems right to me. I wonder if another source of the difference in attitude towards historical greats between philosophers and physicists owes to the fact that physics is a highly formal discipline while philosophy is not for the most part. Having a formal tool set means that there is much less pressure on physicists to return to primary sources in order to really understand the historical development of their field, since the key proofs/formulae/models/observations/whatever can be abstracted away from important primary works and represented in a distilled form without much distortion. But philosophers can neither formalise without distorting the works of the ‘greats’ like Plato or Kant, nor neglect such works insofar as they are still important touchstones in contemporary debates (for better or worse).

I had roughly this view of primary sources in philosophy while I was a physics student (and, increasingly, amateur philosopher). When I started having formal training in philosophy, I changed my mind. I think the disciplines are disanalogous, but not for reasons of formality, as JT suggests. The disanalogy is that in physics, there are comparatively-rapid mechanisms to resolve controversies, and an accepted notion of progress such that progress happens a lot.

Why don’t physicists learn their general relativity from Einstein, and their classical mechanics from Newton? It’s not because the modern textbooks are more readable and better presented (actually, both Newton and Einstein are terrific writers, way better than typical textbook fare). It’s that contemporary physicists understand lots of stuff about classical mechanics that Newton didn’t understand, and lots about general relativity that Einstein didn’t understand, and it’s not controversial among physicists that this is the case or that the new stuff is correct and important.

That’s not the case in philosophy, where controversy is perpetual (I’ve suggested in other blog discussions that this is definitional of philosophy: we stop calling a topic philosophy when it gets past that stage, as physics did in the 17th century). Learning a philosophy topic involves learning the controversy, and I think the historical progression of that controversy is usually helpful in understanding the current field, and usually not summarisable without loss, and without the summariser’s own views having a significant input. I think this is true even for “non-historical” topics – it’s pretty helpful in philosophy of maths, I think, to understand how the contemporary form of the debate evolved out of the Frege-to-Godel period, and pretty helpful in philosophy of mind to see the chain of ideas that went from physicalism to functionalism, and in parallel from behaviourism to functionalism.

(As a side point: if you talk to really good physicists, they read the original sources more often than you might think, though by no means always.)

A lot of the reason physicists learn their classical mechanics from textbooks rather than Newton is because textbooks are better presented. (Whether they are “more readable” depends on what you’re judging.) If you think Newton’s notation for calculus is clearer than the one derived from Leibniz, for example, you’re in a tiny minority. Science textbooks also present exercises related to the material as it progresses, which is the primary means of absorbing such material in a deep way. For large swaths of classical mechanics, what contemporary physicists understand that Newton didn’t is examples and presentations that are clearer and more compact.

The “philosophy is more controversial” explanation for continuing to read primary sources is a common one, but it’s also question-begging. If the topic is Descartes and there’s a lot of disagreement about what Descartes’ position is, why not read a summary of the different interpretations? If problem is that the controversy can’t be summarized “without loss”, what is it about having undergraduates read the primary sources that is supposed to address that problem? Wasn’t the premise that even experts can’t agree on that?

In brief:

– notation is a substantive advance in maths or physics, not just a matter of presentation

– there isn’t any calculus in the Principia

– examples are also substantive advances, not just presentational

If notation and examples are substantive advances, it doesn’t seem as if much ls left to be a “presentational” advance besides a change in font. The normal dichotomy is between introducing a new philosophical or scientific idea/theoriy/etc. and introducing a new way of discussing an idea or theory. That distinction can be vague, but many people thing there’s something to it. Regardless, your standard cuts against the point about primary sources in science just as well. If all those additions are substantive advances, then a typical primary source generally is much longer (appropriately measured in the time it takes to understand) than its equivalent in a textbook. That’s certainly going to be true when you include background material in the article that you can’t skip without loosing understanding (probably including a bunch of not-quite-as-good examples), and often true when just comparing the respective sentences just on that topic. I don’t see why concision doesn’t count as part of what is “better presented”.

In any case, if that’s the relevant standard then secondary sources in philosophy also routinely make substantive advances compared with the primary sources they discuss.

If you don’t think that, for instance, the development of vector notation was a substantial advance in classical physics, or the development of black-hole and gravity-wave solutions to the Einstein field equations was a substantive advance in general relativity, I’m afraid I have to question whether you are in an appropriately informed position to comment on physics pedagogy.

There is also the rather important detail that in philosophy one cannot very easily divorced content from its form. In some cases, it is of course possible to distill an argument into a few steps (a thing we all do), but for much philosophy, you cannot do it without losing a lot – Plato, Augustine, Schopenhauer, Montaigne, Wittgenstein, or Nietzsche are of course the most famous cases, but I daresay it’s true of most philosophy that has lasting value. There is something like an intellectual experience, revelation, or what have you that you can get only by reading the originals. In this aspect philosophy bears similarity to literature.

It is so hard to picture breaking completely from philosophy’s past because one aspect of philosophical rationality involves the attempt to be critical about the commitments that structure one’s thinking. Many if not most of our commitments come from the past, if not from the deep past then from one’s teachers, who themselves acquired philosophical concepts in conditions not of their own making, and so on. This is what makes a philosophical tradition. Every current article on a topic of current concern stands in a tradition of thinking, whether the author of the article knows it or not. If they do not know it, if they do not know the origin of the meanings of the key concepts they themselves use, then their thought does not live up to one important standard of rationality: it is not autonomous, self-determined, but rather determined from without by the meanings that they have uncritically inherited. This is why the history of philosophy is important: it is not primarily a resource to find solutions to contemporary problems, although it can help us do that, but is one of the essential ways that we become self-conscious about what we ourselves think.

Philosophy as it is often practiced can be quite baffling.

Terence Blake writes, ‘There is not a single real concept in this piece, except the presupposed, scientistic, concept of philosophy as problem-solving’. This remark receives 13 ‘likes’ and no objections!

I don’t mean to argue, and I may be misreading the comment, but just to register some incomprehension. How can this be a criticism of the piece? Is philosophy not supposed to solve problems? If not, what is it for? In what way would it be ‘scientistic” to solve a phiiosophical problem? How could anyone approach philosophy as anything other than a problem-solving exercise? Other than this would be a talking-shop with no purpose. How can the profession defend philosophy from the complaints of the scientists who want to close the department when philosophers themselves think the subject is a waste of time?

This approach would entail having a top-ten list of philosophers none of whom managed to solve a problem. Surely it would be not just perfectly fair but also a vital part of the day job to question why they are on the list.

David writes, ‘Fourth, we don’t have enough confidence in our contemporary work to feel comfortable in “closing the book” on the old masters’.

It appears that contemporary pro philosophers rarely if ever read the old masters unless they are on the list of those who didn’t solve a problem, so the situation would be both inescapable. and explicable.

My list of philosophers who solved a problem would include Newton, Darwin and Turing. In each case they (and their contemporaries) solved it so well that we stopped calling the area they were working in “philosophy”.

Hmm. I wonder what philosophical problems they solved. They should. publish.

Philosophy is much more the construction of problematics than the resolution of problems (though it is that too). This is not just my opinion, but is the way philosophy is taught in high schools and university everywhere in France, where I live and teach. This is also the way it is practised here. Bergson, Sartre, Merleau-Ponty, Bachelard, Deleuze, Foucault and Derrida did nothing else, as do Badiou, Stiegler, Latour, and Laruelle today. There is not a single French philosopher who tries to answer a pre-existing question without first deconstructing the question, making explicit its presupposed concepts and underlying problematic, and proposing different (or at least re-worked) concepts and problematics. A question or a problem is not the same when it is taken up into an incommensurable problematic, but only bears a family resemblance to its other avatars. The scientism comes in when one regards philosophy as necessarily proceeding in the same way as the sciences, taken as problem-solving endeavours. This is not even a sufficient characterisation of the sciences, and far less appropriate to philosophy. Is Plato primarily a problem-solver? This is not the most fruitful way of considering his work, especially given that Plato created and gave expression to competing problematics that are still fighting it out to this day. He also did whatever he could to discredit his rivals (e.g. the Sophists) or to eliminate them from the historical record (e.g. buying up and burning Democritus’s books). Badiou’s conception of philosophy as creating the concepts adequate to configuring the interplays and convergences between contemporary advances in the sciences, the arts, psychogenesis, and politics is no doubt too simple, but it is far less simplistic than the problem-solving model. You can’t just gawk at philosophy and count philosophers, do statistical arguments and expect to come up with significant results, that is the worse sort of naive empiricism.

—“Philosophy is much more the construction of problematics than the resolution of problems (though it is that too). This is not just my opinion, but is the way philosophy is taught in high schools and university everywhere in France, where I live and teach. ”

This is precisely what I have been saying, probably a lot less clearly. For me this comment would neatly summarise the problem that needs to be solved. I have read many books that begin by explaining that metaphysics produces no results but is good at clearly formulating intractable problems. This is not your opinion, just as you say, but a fact. or an attitude adopted and taught. What would be completely and utterly your opinion is that this would be a rational approach to philosophy.

If you can agree that the rationality of this approach is a matter of judgement and choice then we have probably resolved our disagreement. We can just agree to approach philosophy in different ways.

Question is it safe to say scientists and philosophers are equally the same depend on one’s field of study or that they are quite the opposite and should never be view as equal only just they both work hard to solve their problem! (Asking for a friend)

The “13 Platos in Attica” argument doesn’t really work even in its own terms. There is a selection effect: we are paying attention to Athens in the 5th century BC because Plato was there; we didn’t pick it randomly. The plausible claim isn’t that Plato is the greatest philosopher in that given period of time in Attica; it’s something more like: he’s the greatest philosopher anywhere in the whole period from (say) 1000 BC to 1000 AD. Eyeballing Gregory Lewis’s graph, there are about three billion people in that period. So there shouldn’t even be one Plato-level person in contemporary Attica, let alone thirteen.

(The more modest claim that the distribution of great philosophers skews old to a degree that would be implausible through random chance is obviously right, whatever larger significance you think it has. I’m quibbling with this extreme version of it, not the modest version.)

Not a lot of women there, oh wait, there aren’t any…

If the worlds capacity for great philosophy, art learning etc. increases with population, shouldn’t our capacity for distinguishing history’s greatest philosophers likewise be at its peak? If the consensus opinion reflects this capacity or anything important, being informed by the greatest teachers/transmitters of information the world has ever seen, why question it?

Philosophical inquiry became scientific inquiry. The major figures you expected too see populating more recent history now work in the domain of science. It’s a family tree, and the tree continues to expand, and thrive. All good.

Despite the growth of the sciences, there are still many more philosophers today than at any point in the past. Given that the vast majority of the greats are from the distant past, the original question remains: why not a larger number of recent greats? Your suggestion would answer the question, I think, only if you meant that despite the enormous number of philosophers in recent history, they are on average much duller than philosophers of the past because the great minds go into the sciences.

There’s a couple things I take issue with here. One, the list is totally skewed towards the “analytic” tradition. Where’s Nietzsche? Heidegger? Second, this whole analysis hinges on the assumption that if there are great philosophers, we would know about it. In order to be a “great” philosopher, does one need to be recognized as such? Why? Third, an assumption that philosophy is in any way cumulative. Are we actually in a better place than those in antiquity? Has our understanding of truth progressed? How could this possibly be measured? I also wonder about the word “greatness.” What makes a great philosopher? Acclaim? Is a great philosopher someone who lives a good life? What is a good life?

To my understanding when they mean by ” great philosophers” is define on how they impacted civilisation and how they open doors for others to past down their most important life works which reshaped our way of understanding since decades to come! Just my understanding and not actual fact.

This is just the sort of naive perspective on the history of philosophy one might expect from someone who, witting or not, belongs to the Anglo-American tradition. Read Richard Rorty.

Are we supposed to believe that this author actually understands Plato, for example? The writing is not that clear as evidenced from the fact that commenters seem to have understood the article as saying Plato was great, while others that he wasn’t.

Or, for example, Aristotle. Why has he had such an important effect on culture, including Islamic culture in it’s first expansion, then on European intellectuals from the 11th centuries when the texts were recovered during the reconquest? There is something unique and elementary in his writing. Was it conscious on his part? Even today screenwriters refer to “Poetics.” Reading its simple sentences somehow interrupts habitual thought patterns. Maybe that was intentional.

There is a “secret” teaching within Plato. Secret because it was only understood by initiates. For example, if you read commentaries on “Theatetus” over the course of history (there aren’t that many) you will find very little understanding because it’s such a difficult text and was only better understood in our time. I suggest this author read “The Rational Enterprise, Logos in Plato’s Theatetus” by Rosmary Desjardins (SUNY Press, 1990).

How can you measure the thinking of men who were born centuries before us? Who fundamentally started the thinking school. I mean it’s a kind of comparison that doesn’t make any sense. How can you know if they were born in our time, with all the knowledge and information available they won’t kind of revolutionize the way of thinking once more? Remember that they started everything from scratch and we just take it and adapt much of their ideas.

Another thing is that in today’s world, people are dumbed down. A typical day (At least the western version of it) after work is filled with useless and garbage entertainment which does not allow a person to think. Garbage TV Shows, garbage music, Garbage movies, etc. And in recent years, to add insult to the injury, we are constantly glued to our mobile devices jumping from app to app serving no specific purpose just killing time and we think we are being productive.

I’d write a rejoinder, but since I only read this comment because I was flipping between websites to kill time, I think it would be a performative contradiction.

This is certainly a revealing discussion. I have learned a lot about how different people view philosophy and their various arguments for and against each view, free of the complication of any actual philosophical disputes to muddy the waters.

I may never find the time and perhaps it would be beyond me, but I would like to take this discussion and turn it into a readable Socratric-like dialogue. Might this this be possible? Anonymity could be preserved or the characters could have their real names, as preferred. DN would have to like the idea and send me the comments as a file. I would undertake not to send the piece to anyone except DN, who can then do with it as they see fit and bin it if it’s no good. I would attempt to resolve issues, highlight agreements and stress the importance of the issues, not present the discussion as an inconclusive boxing-match. I would not promise to finish it or guarantee its value if it is ever finished, but I’d like to make the attempt .

These discussion are often very good but wasted except for the participants, and sometimes this seems a shame.

I couldnt agree more but whats so different today then back in plato era? Wherent those who where considered poor did not have the opportunity to learn and grow in knowledge? As where today we have it at our finger tip and we have the choice to further our education or just be a bum and waste time away! I do understand it seems most are just wasting their time due to all the new technology and cool gadget at our grasp, but would you would you agree that today its our choice if we want more knowledge as where in Plato’s days u had to be considered wealthy and fortunate unlike the poor’s and those who arent allowed to rise above?!

I think the conception of philosophy as “solving problems” is not a very good conception of philosophy at all. At least to me it seems like the kind of thing that somebody who does not really understand why and how people do philosophy would think. In many ways, philosophy is an individual’s reflection on life and one’s place in the world – some prefer this to be more or very personal, some like it to be cooperative reflection, some social situated. But in any case, it is not about solving problems at all – it is a way of wondering and thinking about “problems” – things that are in some sense mysterious, hard to get grip but at the same time seem somehow basic to our existence. This can concern the wonder of language and communication, the sense that there is right or wrong, the mesmerizing fact that somehow we can systematically grasp how the world works, or the depressing fact that we are often cruel and self-destructive. So philosophy really is thinking about such things and thinking it both through the history of our thought (since we do not start from nowhere) and from something like a universal point of view (or, rather, a point of view that can be very personal but demands some sort of universal acknowledgment or justification). It is, in a sense, an odd way of thinking about the world – it’s neither practical but also not purely theoretical. So when we read Plato, we are reading a person who formulated and framed much of the ways in which such thinking moves and we need it to help us think on our own about ourselves. It’s similar to how we need to understand our parents in order to understand what we are. Modern day philosophers (well, Ancient too) often get bogged down in details – of course – but I think people who confuse working out such details with the whole enterprise are not really doing philosophy justice.

Concerning the smartness of Plato and Aristotle compared to people now or whatever – well, who cares? There are people who have devoted their lives to the study of Aristotle or Kant – many, many people. One would assume they would know better and rather devote themselves to the thought of the latest “super-smart” hotshot from NYU or MIT who is already a great philosopher with a fresh PhD since, after all, the chances are statistically in his favor…

Hi Paolo

–‘I think the conception of philosophy as “solving problems” is not a very good conception of philosophy at all. At least to me it seems like the kind of thing that somebody who does not really understand why and how people do philosophy would think. !

If you meant to say that that if a person can solve all philosophical problems then they would not understand why and how people who do professional philosophy think, then I’m sure you;re right.

I see your attitude as the death of philosophy but have no way to prove it other than to point to the evidence,.

Thank you for responding, and to others here, but I would like to drop out of the discussion at this point.

Hmm… some thoughts:

This piece seems to rely on the idea that there is a craft or skill of philosophy (cf. Plato’s fondness for homely arts and crafts analogies) and that how ‘great’ someone is a function of how good they are at this craft/skill. But:

a) There clearly isn’t any one such skill, and certainly not one that is innate. There are several skills and abilities which different philosophers possess in different degrees. These share a ‘family resemblance’, one might say, characterized by rigour, intellectual discipline and tenacity.

b) ‘Greatness’, of the sort predicated of Plato or Kant, doesn’t mean that these people possessed these skills to an exceptional or unparalleled degree. It is a statement of their grandness of vision, historical importance, and the continuing value of engagement with their work.

c) To a great extent this is about picking the right question or focus at the right time. This is no different for other disciplines. The great physicists, for example, are not necessarily the best technical practitioners, they are those who had bold and grand ideas which changed the prevailing doctrines of the field.

d) So in this sense perhaps ‘greatness’ is something that is easier to achieve in periods of revolutionary rather than normal science (or philosophy).

Really, you can only be as great as your time permits. For this reason I’m in some ways ‘declinist’; Plato and Aristotle could be great because they stood at the dawn of the Western intellectual tradition, Aquinas because he marked the collision and synthesis of classical ideas and Christianity, Kant because he expressed the grandeur of thought unleashed in the Enlightenment. I’m not sure that right now there is any such great moment to be marked.

Perhaps the greatest we can be is comparable to Boethius, a last lonely exemplar of a world, rather than Plato, who was a beginning.

As a young engineer back in the late 60’s (the time of the first moon walk and first heart transplant) I often had to go out to sites in the bush. On one route, I would often pass an ox wagon repair workshop – the work horse of the early 19th century but an anachronism when I passed by. My great regret today is that I never stopped and went in to meet the people who worked there and have a look around.

Gregory Lewis’ review of ancient philosophers seems to fall into the same category

One issue here is that, if the poll at the beginning is the one I think it is, it explicitly excluded anyone still living or even recently deceased from consideration. So it’s no surprise that it doesn’t include any such figures, and no further conclusions should be arrived at on that basis.

(That said, it does seem to express something pretty close to a consensus to me, save perhaps having Frege way higher than I’d put him.)

Some more possible factors: It takes a long time before a philosopher’s work is appreciated. Also, the field only has X ‘slots’ for recognized philosophers (just as there are millions of fantastic singers, but only a few ‘slots’ for pop stars in the music industry).

I’m very grateful for the kind remarks and trenchant criticism this post has received. I will try and reply along common themes, and beg forgiveness if I neglect important points along the way.

WHO SHOULD BE ON THE LIST OF GREAT PHILOSOPHERS?

A few remarks were directed at who should be on the list of great philosophers, or that some groups (e.g. women, ‘scholastics’) appear under-represented. Leiter’s original poll was via Condorcet voting of over lots of philosophers by lots of people. ‘Human accomplishment’ (by Murray, of ‘Bell Curve’ fame) uses space in encyclopaedias as his metric for notability, and his ‘top twenty’ for western philosophy is somewhat different:

1. Aristotle

2. Plato

3. Kant

4. Descartes

5. Hegel

6. Aquinas

7. Locke

8. Hume

9. Augustine

10. Spinoza

11. Leibniz

12. Socrates

13. Schopenhauer

14. Berkley

15. Nietszche

16. Hobbes

17. Russell

18. Rousseau

19. Plotinus

20. Fichte

However, this shuffling seems to be among the various candidate ancient greats, rather than an influx of more contemporary figures. I suspect the ideal list which precisely matches common (or expert opinion) will also have considerable pastward skew, although people may of course retain their own idiosyncrasies.

‘INNATE’ PHILOSOPHICAL GREATNESS?

Not being a great (or even good) philosopher myself, I don’t know what exactly ‘what it takes’. I agree that it is not solely a matter of being clever. Insofar as these are ‘natural’ or innate abilities (or at least to whatever degree they are), the natural lottery model looks appropriate. If we say ‘innate’ philosophical skill is some weighted sum of many different abilities, one would expect those with the greatest natural endowment of philosophical ability to be distributed randomly among births, and thus closer to the present.

THERE HAS NEVER BEEN A BETTER TIME TO BE A WHIG HISTORIAN!

I went on to suggest that when we look at whatever else is needed to become a great philosopher besides innate talent, the environment of the present day looks more favourable to that than at any time in the past. Thus the pastward skew is more surprising. This has drawn criticism of whiggishness.

If whiggishness implies some belief in an immutable law that has guided history towards getting better, I am not a whig. But I’ll happily cop to being an optimist about both the present and future: the arc of humankind has in fact risen over time (albeit not monotonically); The current state of humankind is better than any time before, on balance and by the lights of almost all considerations individually – philosophy not excluded.

I think the facts vindicate this view. David notes consuming ‘garbage’ media (TV, music, etc.) and wasting time on our smartphones is a poor way of cultivating ourselves to do great philosophy. But if we manage to get to the ‘consuming intellectual garbage stage’, we have gotten far further than the majority of those living in the past: dying in childhood, being a slave, being poor, being illiterate, being female, and so on, and on, and on. I think declinist accounts of the modern day require an extremely jaundiced view of the present, and a rose-tinted one of the past. Consider the option of re-drawing your ticket in the birth lottery, being randomly allocated to be born as a random person at some time in the past versus the present. I think no one would seriously contemplate such an offer – even if they wanted to be a philosopher.

Paolo notes that this line of argument can be applied to other fields outside philosophy, and takes this as a reductio. I regret to disappoint them and say I would endorse these conclusions. The human capital of the present seems almost certainly better than any time in the past across almost all fields of human endeavour. (Although it is worth noting that ‘greatest ever’ lists of novelists, scientists, etc. tend not be skewed so heavily into the past).

OTHER FACTORS IN PERCEIVING GREATNESS

Sobel notes another possibility for why greatness is past skewed – we need time to work out who was really a good philosopher, and so it would be too early to tell where contemporary great philosophers stand in the ‘all time rankings’. Heikkinen also notes the poll I used excludes very recent figures, although I suspect if they were included, they would not be placed high enough in the rankings to defray the pastward skew (c.f. Murray’s list above).

This seems right insofar as it goes, but I don’t think it is sufficient to explain the entire trend. We are happy to claim reasonably recent figures (e.g. Wittgenstein) as ‘all time’ greats. The population of the 19th Century still remains vastly greater than that of the 5th Century BCE.

I also agree with Wallace’s point about selection bias – I obviously did pick ~500 BCE Attica because it contained Plato, and a priori the chance of Attica having the ‘best philosopher ever’ in the toy model is no better or worse than any other group of ~300 000 people. I would however aver the example manages more than provocative hyperbole: discounting Plato, the best philosopher in that Attican population is Aristotle, and modern day Attica doesn’t have 13 Aristotles either.

WHAT HAS ATHENS TO DO WITH US?

I learned a lot from the various meta-philosophical threads. Perhaps in some cases the topics of philosophy get subsumed into another field (e.g. science) – although, as noted by others, the raw numbers of philosophers seem much greater, even if there has been ‘field dilution’.

I know it is a well-worn topic about whether philosophy can be said to make progress or not. Perhaps instead of being a scientific endeavour where there is a sense of resolving controversy and getting closer to the truth, philosophy is more like literature: although there are new developments, ideas, and patterns of influence, we might be reluctant to say modern playwrights have made progress beyond Shakespeare in the same way modern physicists have made progress beyond Newton. This would not explain the pastward skew, but would provide further reason to study the work of the ancient greats.

As an amateur, my grounding in how the modern academy regards the ancient greats is patchy. I am thus particularly grateful for the remarks by ‘ancient student’ and ‘CF’. If (as Per suggests) modern philosophers engage with the ancients in a more robust and less (as ‘post-doc’ suggests) ‘Talmudic’ approach, I am glad to be mistaken; I find it hard to object to ‘ancient’s students’ approach, which he takes as representative of their field (“we make the best interpretations of the arguments in the texts possible, trying not to facilely dismiss the arguments contained, uncritically accept them, or substitute a good argument for the authentic one.”)

I nonetheless wonder how much benefit this careful philosophical history can provide to what I call the ‘subject matter’ of philosophy. I believe for every word of Plato’s we have, we also have thousands (tens of thousands? more?) words of secondary literature discussing his work. Most philosophers don’t benefit from this careful attention, and it is not obvious that we would gain less from similar study of their work to Plato (Paolo again notes this as a reductio, and I again regret to disappoint them by accepting it).

‘ancient-student’ notes that ancient philosophy may be particularly edifying, coming as it does from a distant cultural millieu. Yet (as CF implies) there are many other similarly or more distant millieu’s whose philosophical work is much less well studied than ancient Greece. Perhaps ancient greece is in a goldilocks zone of remoteness to the present day, but if our objective is to inform and enlighten current philosophical practice, there seem many different fields of philosophical thought which are relatively untouched compared to the ancient greek tradition.

I accept instances of ‘rediscovery’ (and consequent influence) of their work count against my hypothesis. Against this hard data, the best I can counter is with a thought experiment: if (for example) a large tranche of Aristotle’s work was rediscovered, it would be a great boon for philosophical history, but I think it would not greatly inform modern philosophical practice.

Plato wasn’t first. Thales was first, and wasn’t that great. Plato was great enough to make everyone think he was first.

There are many things assumed, and many not clarified.

– You assume that all those achievements were low-hanging fruits. They are, only in hindsight. Before Indians described zero, which is so ubiquitous now, the whole world struggled with it. If it was such a low hanging fruit, why didn’t so many people discover it much earlier? Also, you say sweeping discoveries, low heights to scale to reach limits, are all in hindsight. If you didn’t know what the scale is, how could you know how high you have to climb? Going by your logic, 500 years from now, quantum mechanics would appear like a low hanging fruit, and somebody might say, that particular human got that breakthrough only because he was born earlier than them. Your whole argument seems to me like hindsight bias, only, you weren’t present in the past.

– These people are worthy of praise, because, despite their obvious disadvantages like lack of prior knowledge, lack of real purpose in their time, lack of reward in their time, they thought what they thought and pursued it.

– It was an interesting read, and good luck with all your philosophical quests. One thing I also found lacking was the eastern philosophers. Obviously, you don’t think that all great philosophers were from the west. It would prove you more useful If you acquainted yourself with other half of the world.