Doing the Best By Their Opponents

Which philosophers or philosophical papers do the best at presenting compelling and sympathetic cases on their opposition’s behalf, so that even if you’re unfamiliar with the general issue, you come away from the paper thinking, “Well, if they can answer that case, there isn’t going to be much more to be said”? Which philosophers or philosophical papers present particularly convincing cases for the other side?

Thanks to Jeremy Fantl (University of Calgary), for giving me permission to repost this query of his which he first put on Facebook. Your suggestions, readers?

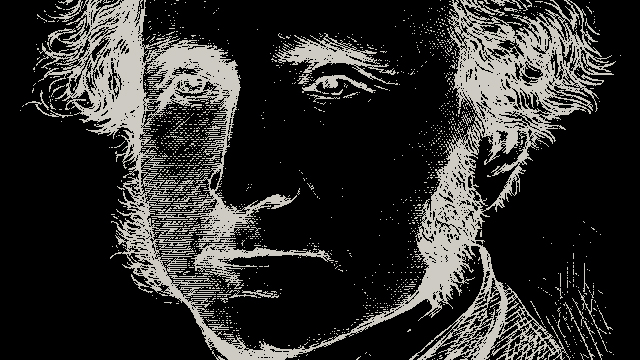

And just because it’s so good, here is a classic passage from Chapter 2 of Mill’s On Liberty:

He who knows only his own side of the case, knows little of that. His reasons may be good, and no one may have been able to refute them. But if he is equally unable to refute the reasons on the opposite side; if he does not so much as know what they are, he has no ground for preferring either opinion. The rational position for him would be suspension of judgment, and unless he contents himself with that, he is either led by authority, or adopts, like the generality of the world, the side to which he feels most inclination. Nor is it enough that he should hear the arguments of adversaries from his own teachers, presented as they state them, and accompanied by what they offer as refutations. That is not the way to do justice to the arguments, or bring them into real contact with his own mind. He must be able to hear them from persons who actually believe them; who defend them in earnest, and do their very utmost for them. He must know them in their most plausible and persuasive form; he must feel the whole force of the difficulty which the true view of the subject has to encounter and dispose of; else he will never really possess himself of the portion of truth which meets and removes that difficulty. Ninety-nine in a hundred of what are called educated men are in this condition; even of those who can argue fluently for their opinions. Their conclusion may be true, but it might be false for anything they know: they have never thrown themselves into the mental position of those who think differently from them, and considered what such persons may have to say; and consequently they do not, in any proper sense of the word, know the doctrine which they themselves profess. They do not know those parts of it which explain and justify the remainder; the considerations which show that a fact which seemingly conflicts with another is reconcilable with it, or that, of two apparently strong reasons, one and not the other ought to be preferred. All that part of the truth which turns the scale, and decides the judgment of a completely informed mind, they are strangers to; nor is it ever really known, but to those who have attended equally and impartially to both sides, and endeavoured to see the reasons of both in the strongest light. So essential is this discipline to a real understanding of moral and human subjects, that if opponents of all important truths do not exist, it is indispensable to imagine them, and supply them with the strongest arguments which the most skilful devil’s advocate can conjure up.

Speaking of Mill’s On Liberty, David Lewis’ paper “Mill and Milquetoast” is a classic case of the phenomenon here.

Lewis’s intentions might have been charitable, but I think he makes a hash of On Liberty, especially Mill’s assumption of infallibility claim, in that paper.

I don’t have a suggestion but love the passage from Mill. I would see it as an argument for the ‘Principle of Charity’, a much underused method.

To my mind, Gilles Deleuze’s little 1963 book, Kant’s Critical Philosophy, is a marvel. Deleuze says he wrote the book in order to get to know his enemy. Yet it’s one of the most sympathetic, faithful, and pointed interpretations of Kant’s thought I know. It’s brief, deep, and comprehensive, all at once. Only someone who really worked to see things from Kant’s point of view could present Kant’s entire philosophy so pithily.

It seems to me that representing the opposing view as well as feasibly possible is a signal marker of a true intellectual, and the value and reasons behind this practice should be talked about more. Two things worth thinking about are: 1) why is it a good thing to do, and 2) who doesn’t follow this practice, and why?

Why it’s a virtuous practice (assuming it is)

Theory 1: It helps us discover our biases, etc. (see Mill above). This is a “cognitive” benefit and the virtues at work are very intellectual. But then again, there may also be…

Theory 2: Failing to do so somehow isn’t “fair” to one’s opponents, or is boring, not fun or challenging. This one is based on a more agonistic picture of academic discourse (“vigorous debate,” “don’t attack a strawman,” [to an opponent] “now what you *should* say is …” etc.). This model is more personal (about doing right by opponents as opposed to their views—e.g. Justin’s title), ethical in its rationale, and maybe “non-cognitive.” (http://philpapers.org/rec/DEMFTC)

Okay, who doesn’t follow this “charitable” model? It seems to me there are at least two other common practices:

Lawyerly model: “Maybe my opponents can make a good case, but that’s their job, not mine.”

Activist model: “My opponents are evil, or their agenda is evil, so it’d be wrong to present their views/view x in its most reasonable form, lest it attract further adherents or make it seem more reputable.”

I think sometimes being lawyerly in this way is good pedagogy (think of Socrates’ playing dumb with highly uncharitable interpretations early on in dialogues in order to help his students/interlocutors learn to state their views more precisely). But when you’re writing to peers? Not so sure. W/r/t the activist model…tougher for me to find cases when that would be a good thing. Mockery and political rhetoric is one thing, but in a supposedly academic context?

G.A.M. Enscombe’s classic paper “Contemporary Ethics” presents the work of post-Sidgwickian ethicists in such fair and flattering terms that one can hardly believe that at the end of the paper, she ultimately has to reject their views. And, as Bimon Slackburn has pointed out in his glowing review, Malasdair AcIntyre’s _Simultaneous with Virtue_ presents so-called “emotivism” so clearly and persuasively that it’s no surprise that, as a matter of sociology, nearly all of us working in ethics today count as emotivists. The work of L.J. Mackie and William Bernard is similarly charitable to opponents. And let’s not forget *St.* Peter Strawson, not to be confused with *Sir* Peter Strawson, who definitely did NOT compare his opponents’ metaphysical commitments to “intellectualist trinkets.” It seems that there’s something about the genre of moral-philosopher-who-wants-to-start-ethical-theorizing-anew that requires charity of just the sort Fantl is looking for.

If only I could get away with being so charitable in my papers.

I am disturbed at how few submissions there are to this thread. Philosophers are apparently better at funny footnotes than they are putting their opponents in their best light.

In Being & time, Heidegger spends a good portion presenting opposing views before making his point. A specific one I have in mind is the discussion of Descartes’ cogito ergo sum in I-3B “A Contrast between our Analysis of Worldhood and Descartes’ Interpretation of the World”. In this discussion, Heidegger summarizes the account given by Descartes in his mediations and extracts the ontological assumptions underlying his description of the world, thus showing how it breaks down. It’s not a sympathetic account: he says, “The considerations which follow will not have been grounded in full detail until the ‘cogito sum’ has been phenomenologically destroyed”, which task however, was supposed to be developed in a section that did not get written and published.

Okay, I have a clear case. Mark Schroeder’s Being For is critical of expressivism, but in order to put himself in the position to make really powerful criticisms of it, he has to lay out a formulation of expressivism that enables it to avoid a shit-ton of difficulties for the view.

In the spirit of James Bond, I respect M’s remarks above, and Justin Coates’ as well.

Rich Aquila gave me this advice many years ago in grad school (paraphrased): “Don’t just know your adversaries’ position–know it at least as well and preferably better than they do. Because only then will you know that your counterarguments are right.” And I’ve tried my best to adhere to that.

But whether I have or not, my main area of interest–free will, responsibility, and action theory–seems to be one that has embodied Rich’s spirit of criticism. Read work by Watson, Wolf, Beebee, Vihvelin, Fischer, Mele, Pereboom, Smilansky, Vargas, Nichols, Steward, van Inwagen. . . you find an intellectual honesty about opponents as praised in the OP, and more than that, real respect and humility for one’s own position. For one outstanding instance, I’d select van Inwagen’s “Free Will Remains a Mystery”, where he concedes that his famous Beta principle was fallacious and offers an alternative account, but finally takes a mysterian position rather than a defiant one. Reading that piece changed me–it redefined Rich’s advice for epistemic humility in terms of another first-class philosopher acknowledging the force of argument above all else.

Does anyone have any suggestions about what we can do to increase charity in the discipline? It seems to me that we need a good deal more, especially where political and moral disagreements we care about are involved. Certainly, we can strive to be charitable personally and to train our students to be charitable, but is there more we can do to foster charity?

Terry Eagleton, The Illusions of Postmodernism. A sympathetic polemic against it.