Philosophers On the 2016 U.S. Presidential Race

How is it that, at the same time, possibly the most principled and possibly the least principled politicians the U.S. has seen in recent times are both serious contenders for the presidency? How are voters weighing the progressiveness of supporting a woman candidate for president versus the regressiveness of creating another political dynasty? What does the failure, to date, of any serious conservative or libertarian candidate tell us about what people in the U.S. really value? These are just a few of the questions that the 2016 U.S. presidential election raises.

It is a strange election so far, and its strangeness serves to highlight important issues that are present in many elections, including issues in political philosophy, epistemology, and ethics. What does this election tell us about voting, democracy, and democratic theory? What lessons does it hold regarding political participation, civic virtue, and education? What has been the role of emotion, rhetoric, and ideology in the campaigns? What conclusions about political epistemology, if any, should we draw from the election so far?

To discuss these questions and others, I invited philosophers and political theorists to share some brief remarks about the election to date. As with previous installments in the “Philosophers On” series, these remarks are not comprehensive statements, but rather focused thoughts on specific issues, meant to prompt further discussion, here and elsewhere.

Contributing are:

- Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse (Vanderbilt University) — The Party’s Over

- Elisabeth Anker (George Washington University) — Trump’s Melodrama

- Jason Brennan (Georgetown University) — Democracy Works Because It Doesn’t Work

- Michael Fuerstein (St. Olaf College) — A Hollowed-Out Civic Experience

- Alexander Guerrero (University of Pennsylvania) — Update the ‘Old Technology’ of Elections

- Suzy Killmister (University of Connecticut) — Democracy, Speech, and Punishment

- Gina Schouten (Illinois State University) — Does it Matter that Clinton Is a Woman?

Thanks to each of them for taking the time to share their thoughts here.

The idea of the “Philosophers On” series is to explore the ways in which philosophers can add, with their characteristically insightful and careful modes of thinking, to the public conversations about current events, as well as prompt further discussion among philosophers about these events. All are welcome to join the discussion.

Please share the post with others, and feel free to provide links in the comments to relevant philosophical commentary elsewhere.

Scott Aikin and Robert Talisse — The Party’s Over

We have never embraced political conservatism. However, we also think that the conservative tradition in American politics is intellectually formidable. We find the best representatives of that tradition to be rigorous, insightful, and philosophically astute. They are political commentators for whom ideas matter. In their best work we find proposals and principles that we think are incorrect, but never merely stupid.

The trouble with political conservatism in America is that for the past fifty years, its central ideals have been growing increasingly unpopular with the American citizenry. The sociological, demographic, and economic explanations of this need not detain us. The fact is that the core conservative values of personal responsibility, self-reliance, restrained government, shared community, and the moral authority of tradition have given way to tendencies that conservatives must regard as base and uncivilized: insatiable appetites for luxury, excess, spectacle, and power, all of which are social forces that dissolve tradition and foster divisions. It is no accident that W.F. Buckley Jr. defined conservatives as standing athwart history yelling, Stop!

This cultural shift naturally presented a challenge to the Republican Party, which was faced with a social reality in which winning elections on the basis of their core values was bound to become increasingly unlikely. Again, conservative intellectuals understood that their ideas were bound to be seen as badly out of step. And so they needed to find other ways to win elections beyond explaining their core ideas to what they saw as a fractured populace. What was needed was a way to build a political coalition among people who ultimately have little in common. And this required a strategy by which deep-seated divisions could be overshadowed by some unifying purpose. With the citizenry divided, this unifying purpose needed to be manufactured.

Alas, the formation of political unity is not as difficult as it may seem, for it is easy to construct nemeses: social and cultural forces that threaten to thwart, disfigure, nullify, or dilute whatever makes America great. Note that in manufacturing such an antagonist, one mustn’t get specific about the nature or target of the threatening body. It is enough to simply characterize it as alien and hostile, or debauched and decadent, thereby allowing each citizen to fill in the details however he or she sees fit. The rest is left unsaid, and this was presented as a matter of etiquette. But it was strategic. A silent majority, insofar as it is silent, doesn’t speak. And insofar as it doesn’t speak, it doesn’t speak to itself, and so it cannot discover how deep its internal divisions may run.

It is crucial to remember that the Republican strategy initially was to merely manufacture an enemy around which to unify an otherwise divided citizenry for the purpose of winning elections. Once in office, Republicans could govern according to the traditional conservative values that they had downplayed or omitted from the narrative while campaigning. To be sure, this kind of bait-and-switch may seem cynical and disingenuous, but it is the stuff out of which democratic politics is made.

The most recent national election cycles have shown the hazard of this strategy. One might say that the bait-and-switch has come full circle: The artificial foe has become the concrete enemy, the instrument has become the end, and the rhetoric has become the substantive message. At least since Reagan’s presidency, the Republican Party has undergone a fateful transformation, most evident in the progression from Newt Gingrich’s Contract with America to the Tea Party and Sarah Palin to Donald Trump. The resentment, anxiety, and fear that was once deployed as a device to motivate voting behavior is now the official party platform.

In this way, Trump has already won. The Republican Party is no longer conservative, as the Party is no longer devoted to ideas of any kind. In fact, it is committed to the idea that ideas do not matter. And, importantly, this means that Trump has won even if he does not win the GOP nomination (though it currently seems that he will), for he has demonstrated that in order to get the support of voters who identify with the Republican Party, would-be candidates must vilify ideas as such and instead communicate solely in one-liners — empty slogans, vulgar innuendo, and childish insults. All this in the service of selling what is vaunted as a brand. Conservatism was supposed to be the idea that values were more than brands, but branding is now all the Republican Party has at its rhetorical core.

There is good reason to think that the GOP nominee will not win the White House in the coming election. Although we are pleased by this thought, we also cannot help but find it disconcerting that, with respect to the Republicans, the Party’s over.

Elisabeth Anker — Trump’s Melodrama

One of the most important and vexing questions in current politics is why presidential candidate Donald Trump galvanizes such a large percentage of the US population. Support for Trump’s “Make American Great Again” campaign extends far beyond the white supremacists attracted to his nativistic appeals. Trump’s political rhetoric is a key part of his broad backing, but why it is so remains unnoticed among critics who focus on his seemingly spontaneous and statistically third-grade level diction. Trump posits that Americans are the unjust victims of economic hardship and political exploitation, which are manufactured by scary, evil villains who can only be stopped by heroic state actions that will restore a diminished sovereignty. He emphasizes the wounding of virtuous and innocent citizens by evil Mexican immigrants, Muslim refugees, and Chinese trade imbalances, and he depicts a border wall, aggressive unilateral state action, and military expansion as moral imperatives to ameliorate citizens’ suffering and re-achieve greatness. Trump, in other words, deploys the popular and galvanizing political discourse of melodrama.

Melodramatic political discourses, as I have argued in my book Orgies of Feeling: Melodrama and the Politics of Freedom, portray political events through moral polarities of good and evil, overwhelmed victims, heightened affects of pain and suffering, grand gestures, and astonishing feats of heroism. In America, they often emphasize national goodness though the suffering of the US nation-state, diagnose evil in political opposition, and find heroism in acts of state and individual sovereignty that can eradicate villainy. Melodramatic political discourses equate feelings of powerlessness with virtue and innocence, and they solicit affective states of astonishment, sorrow, and pathos through scenes of injured citizens. They often promise that sovereign state power can eradicate villainy and restore individual freedom. Melodrama has been a popular form of American political discourse throughout much of the twentieth century, but Trump takes melodrama to heightened levels as he uses it to address the intensifying effects of neoliberalism, globalization, and precarization that relentlessly besiege millions of Americans. He taps into their felt powerlessness by diagnosing it as unjust victimization from foreign job-stealing plotters, and promises to restore imperiled individual freedom by reinvigorating exclusionary forms of state sovereignty.

Trump draws upon melodrama in part because it is particularly adept at articulating ineffable feelings of vulnerability. His melodramatic speeches detail “Americans decimated” by villainous Mexicans who steal US jobs, violently destroy American cities, and rape and murder innocent American women (women are the ultimate melodramatic victim — tied to the railroad tracks and waiting helplessly for the hero.) They depict Muslim refugees as uncivilized barbarians hoping to arrive in the United States solely to murder and behead the innocent Americans they hate. They decry the Chinese government nefariously stealing the economic power and global sovereignty that rightfully belongs to hard-working American citizens. Trump’s melodramas portray the United States as both the feminized, virginal victim and the aggressive, masculinized hero in his story of Making America Great Again.

Trump’s overheated melodrama is thus not the mark of unsophisticated thought, but a powerful political strategy that foments the feeling of being overwhelmed by power. Trump deploys it to argue that violent and punitive forms of state expansion, especially strong borders — whether a concrete wall, draconian detention, or blocked visas — plus an impermeable military can end them. “We’re gonna make our military so big and so strong and so great, it will be so powerful that I don’t think we’re ever going to have to use it. Nobody’s going to mess with us.” It is a promise that state power, so big and so strong and so great, can wipe away all experiences of vulnerability. Trump’s vision of sovereign power may seem philosophically incoherent — he promises individualism and global control, self-mastery and mass detention, border walls and unbound power– but it is politically compelling. Make America Great Again, in other words, transmutes affectively intense experiences of vulnerability into the justification for state violence imagined as sovereign freedom.

Trump’s melodramatic promise is this: you may feel weak and injured now, but my state policies will soon overcome terrifying villains and allow you to experience your rightful, and unbound, power. This helps to explain why Trump’s support is especially strong from white, male supporters. It is not that they are the population most injured by the economic recession or diminished state sovereignty, for instance, but that they feel unable to achieve what they have always been told is their rightful entitlement. Their rightful entitlement, Trump knows, is to be him: economically dominant, a master over self and others, and beholden to no other. His promise to recapture the sovereign freedom he claims to embody is most compelling for those people who have historically and fervently invested in heroic individualism, typically the white men upon whom it is implicitly modeled. Trump’s adherents surely feel threatened by the rise of women and minorities to positions of political power and public visibility, but they, like many others, also feel at the mercy of economic and political forces that few people can identify or understand. Indeed, the individualism they desire disavows the very impact of these larger forces on their lives. Yet this explains how Trump’s melodrama also gains broader appeal than just the avowed white supremacists who support his campaign. His vision of individual sovereignty is broad-based enough that it appeals to women and minorities in greater numbers than one might otherwise expect. Trump’s melodrama may therefore become more appealing as the election wears on, as the robust sovereign individualism he claims to embody continues to decline in possibility for all Americans.

Jason Brennan — Democracy Works Because It Doesn’t Work

In general, democracy works because it doesn’t work. Trump and Sanders are populist candidates who play to misinformation, anger, and prejudice. Trump is doing well this time around because democracy is working, because there has been a break down in various checks parties place on voter ignorance.

Here a few basic truths about voter knowledge and behavior. First, the mean, median, and modal amounts of basic political knowledge among voters are low. Second, voters have systematically different beliefs about how the market or government functions when compared to economists or political scientists; these differences are not explained by differences in demographics, but by differences in knowledge. Third, voters are systematically biased and irrational in how they process political information. Fourth, voters do not generally vote their self-interest, but instead vote in ways that they regard as expressing fidelity to their moral ideals. In short, voters are in general ignorant, irrational, and misinformed nationalist sociotropes.

Given how little voters know and how badly they process information, it’s not surprising that democracies frequently choose bad policies. But given how little voters know and how badly they process information, it’s surprising democracies don’t perform even worse than they do.

In fact, there’s a significant gap between the policies the median voter prefers and the policies actually get implemented. Though modern democracies make plenty of bad choices, in general, they do significantly better than one would expect, given how silly and misinformed median voters are. What seems to explain this is not the “wisdom of the crowds”—the median voter is not wise—but instead that in democracies, political parties, elites, bureaucrats, and others have significant leeway to act independently of voters’ wishes. If you think democracy is a good thing in itself, perhaps that upsets you. If instead you think, as I do, that democracy’s value is purely instrumental, and that political systems ought to be judged by how well they deliver on procedure-independent standards of justice, you should be happy. For the sake of my children and the world, thank goodness America democracy generally doesn’t work, i.e., doesn’t just give the people what they want.

Recently, political scientist Martin Gilens measured how responsive different presidents have been to different groups of voters. Gilens finds that when voters at the 90th, 50th, and 10th percentiles of income disagree about policy, presidents are about six times more responsive to the policy preferences of the rich than the poor.

Gilens is in some ways horrified by results like these, but he admits, there’s an upside. Voters at the 90th percentile of income tend to be significantly better informed than voters at the 50th or especially 10th percentile, and this information changes their policy preferences. For instance, high income Democrats tend to have high degrees of political knowledge, while poor Democrats tend to be ignorant or misinformed. Poor Democrats more approved more strongly of invading Iraq in 2003. They more strongly favor the Patriot Act, invasions of civil liberty, torture, economic protectionism, and restricting abortion rights and access to birth control. They are less tolerant of homosexuals and more opposed to gay rights. In contrast, high information Democrats—such as party elites—are more strongly in favor of free trade and the strong protection of civil rights, and are less interventionist.

Policy-wise, Trump is for the most part a moderate, centrist, populist candidate, though one prone to narcissism and ghastly displays of xenophobia. It’s worth noting here that most political moderates are not moderates on every issue; rather, they are moderate on some and extremist on others, but their positions average out. Thoroughgoing moderates are rare. Trump is rising as the likely Republican nominee despite widespread opposition from the party elite, and despite not sitting well with core Republican voters, because he strongly appeals to disaffected, middle-of-the-road Americans. Trump is what happens when the various safety mechanisms in place in modern democracy—mechanisms that prevent the people from getting what they actually want—start to break down.

Michael Fuerstein — A Hollowed-Out Civic Experience

Even Trump himself doesn’t seem to believe his own bullshit, but the primary results so far suggest that plenty of voters do. Or do they? I’m not sure. The most striking thing about Trump is that, beyond promising to build a wall on the Mexican border and ban Muslims from entering the country, his candidacy is not based on any discernible policy positions. Trump’s platform is Trump, and its main plank is his middle finger.

It seems to me that Trump illustrates a couple of features of democracy worth noting. The first is that voting, and political behavior more generally, is driven as much by emotional responses to people, institutions, and events, as it is by judgments or preferences about who is likely to be a good leader. Trump supporters are apparently angry about the status quo and fearful of social and economic changes that they perceive as a threat. Choosing Trump appears to be as much an expression of those feelings as it is a manifestation of some belief that he will do something good as an office-holder. That is why the almost comical vacuity of Trump’s policy agenda (“we’re gonna be great again!”) is beside the point for his supporters. The second is that political behavior is driven as much by group identification as it is by individual values or beliefs. Trump has given voice to a constituency of white, working class voters that believes itself to be under threat by Mexicans, Muslims, and PC liberals among others. His alarming racist rhetoric and innuendo has served as a rallying cry that defines and accentuates a particular in-group vs out-group narrative. Supporting Trump seems to have become a way of signaling in-group membership as much as anything else.

I think these observations have significance for how we think about addressing some of our democracy’s ailments. In democratic theory, the reigning model for the last couple of decades or so is “deliberative democracy” which, in brief, recommends a free and egalitarian exchange of reasons as the basis for democratic decision-making. But while we undoubtedly would benefit from more reasoned deliberation, the observations above suggest that improving our democracy will depend as much on measures that facilitate the development of our emotional as much as our cognitive faculties and engagement. A healthy democracy is one, not only in which citizens are reasoned and informed, but also one in which they have the capacity to feel sympathetically about the problems and concerns of others, and to leverage a sense of shared experience and identity across social categories. Cultivating such capacities has traditionally been the role of public schools in the United States, as well as public museums, parks, and universities, all of which—at their best—can function as incubators of meaningful, sympathetic social interactions among disparate social groups. From this point of view, Trump is a reflection, not only of a breakdown in social reasoning, but also of a society with an increasingly segregated, defunded, inegalitarian, and hollowed-out civic experience.

While there has been some notable philosophical work of late addressing this emotional/experiential dimension of democracy (e.g., Martha Nussbaum, Political Emotions, Elizabeth Anderson, The Imperative of Integration, Sharon Krause, Civil Passions), I think that democratic theory would benefit from a broader shift in its agenda toward engagement with these concerns, and with an exciting body of relevant work in psychology. From the standpoint of democratic practice, I think that American society would benefit from a vigorous reinvestment in its public crossroads, and from a policy effort to limit the escalating pressures of segregation across economic, racial, religious, and political lines.

Alexander Guerrero — Update the ‘Old Technology’ of Elections

Here’s something puzzling: Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders are leading candidates for president of the United States. Donald Trump—with the hideous gold buildings and beauty pageants, the endless series of wives and bankruptcies, the moronic and bullying bluster; Donald Trump—a fraud of a human being, an inept billionaire whose catchphrase is “you’re fired,” is a leading candidate for president. And, in the other corner: Bernie Sanders, America’s lonely socialist, 75-years old, who has been wandering in the wilderness in Congress for two-and-a-half decades, has somehow stumbled into a serious presidential bid. To add to the oddity, they couldn’t be more different. Trump, while pretending to be a populist for a few minutes, aims to implement tax cuts for the rich beyond anything George W. Bush considered. Sanders, with decades of principled droning on behind him, would like to institute democratic socialism to rival Scandinavia. Trump doesn’t want to jump to conclusions about David Duke; Sanders is releasing mixtapes with Killer Mike.

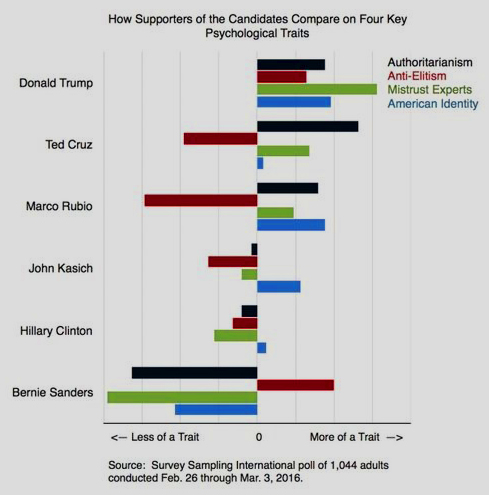

What is going on? A recent study from two political scientists, Wendy Rahn and Eric Oliver, helps shed some light on this question. They conducted a national survey, assessing characteristics of various candidates’ supporters along four dimensions: authoritarianism, anti-elitism, mistrust of experts, and the importance of American identity.

Trump supporters were more authoritarian than any other candidate’s supporters except for Ted Cruz’s, and had the highest scores along both the mistrust of experts and importance of American identity dimensions. Sanders supporters were the exact opposite on those three dimensions: they were the least authoritarian, the most trusting of experts, and put the least importance on identifying as American. Strikingly, however, Trump and Sanders supporters both had, by far, the highest scores with respect to anti-elitism. Rahn and Oliver assessed anti-elitism in terms of agreement with statements like:

“It doesn’t really matter who you vote for because the rich control both political parties”

“Politics usually boils down to a struggle between the people and the powerful” and

“The system is stacked against people like me.”

These are the most compelling ideas this election cycle. People—to an unprecedented degree—feel that the system is broken.

They aren’t wrong. The empirical work of Martin Gilens and others suggests that the rich usually get their way. The rich are not stupid; they try to avoid throwing their money away. People worry about Citizens United, but experts agree that the largest problem isn’t buying elections (which turns out to be hard to do: ask Jeb! and Marco Rubio), but post-election access and lobbying. One just has to look to see how much money is spent on lobbying by the defense, pharmaceutical, insurance, medical, oil/gas, securities/investment, and telecommunications industries to see that something is being sold, and something is being bought. There are questions about whether the policy proposals of either Sanders or Trump would actually help those struggling—diagnoses of false consciousness, wishful thinking, and manipulation are common. But they are both staking their campaigns on this issue: government by the people and for the people (or, at least, for our people, in the case of Trump), rather than by the rich and for the rich.

Many have thought that electoral democracy is the best system possible to ensure government by the people and for the people. So, what is going wrong? Elections set up a principal-agent problem. We are to choose a small subset of people who will act on our behalf. That’s always tricky. What if those people just look out for themselves, or for the most powerful? Here is the genius of elections: if those elected aren’t for the people, we can vote them out. There is an accountability mechanism. Here is the problem: that mechanism only works if we can hold our elected officials meaningfully accountable. And that requires not just free and open elections, but also real choices between meaningfully different options, and—most important—knowledge regarding who has done what, and whether what they have done is good for us, for the country, or for the world. The anti-elitism of Sanders’s and Trump’s supporters reflects a sense that this mechanism is failing us.

There are many different reasons why this might be, but I think the most fundamental one is modern policy complexity coupled with our thoroughgoing ignorance. We are broadly ignorant about what our political officials are actually doing or trying to do, ignorant about the details of complex political issues, and ignorant about whether what our representatives are doing is good for us or for the world. This ignorance means that we can’t hold the elected officials meaningfully accountable. And we don’t. We elect them, and it is as if we have chosen them to sit at the levers of power on the other side of a brick wall. Every two or four or six years they return to our side to tell us what they have been doing, and if we like what they say, we elect to send them back to the other side. But that’s not meaningful accountability. More troubling, if money buys access to the other side of the wall, or even hours at the levers, as it does, then our ignorance permits the capture of our political officials—leading to obscene levels of defense spending, unreal pharmaceutical profit margins, continued entrenchment of oil interests and friendships with Saudi dictatorships, wars as business ventures, the opening of tax shelters and closing of homeless shelters, “too rich to jail,” private prisons, and on and on.

Elsewhere and in ongoing work, I argue that we should consider using lotteries, rather than elections, to select our political officials; that we should consider eliminating the elected individual presidency; and that we should move away from flawed models of accountability through elections and toward models that result in good and responsive policy through demographically representative control of political power and the elimination of avenues for financial influence from the few. There’s not room to make that case fully here. But there is reason to take seriously that electoral democracy may be old technology—better than what came before, and certainly better than authoritarian tyranny, but capable of being improved upon. Here’s where neither Sanders nor Trump is being radical enough. We don’t just need to change who the captain is; we need a new way to travel. As the supporters of Sanders and Trump say: we need a revolution, we need to make America great again. Or for the first time.

Suzy Killmister — Democracy, Speech, and Punishment

At the risk of gross understatement, the current election cycle does not inspire much confidence in the state of democracy in the United States. Rather than try to identify a single, unifying, explanation or diagnosis for these democratic woes, I’m going to focus more narrowly on two refrains that have emerged from this campaign, and consider their relevance for the state of democracy in the US. The first is the refrain, common amongst Trump supporters, that ‘he is finally saying out loud what we’re all thinking’ —a reference, I’m going to assume, to Trump’s outspoken bigotry. The second is a refrain, expressed by some Sanders supporters, that if Clinton wins the nomination they will vote Trump in order to ‘burn this place down’ —where ‘this place’ presumably refers to the political establishment and the institutions that house them. I take the first refrain to signal a threat to democratic relations between citizens; I take the second refrain to signal a threat to democratic institutions.

With respect to the first refrain: we might wonder whether Trump’s declarations of bigotry really matter, if indeed they are merely echoing what many of his supporters were already thinking. The reason they matter is that having such bigotry declared out loud, by a potential Presidential candidate, and then seriously engaged with by the nation’s media, has the power to alter the relations in which citizens stand to one another. Such vocal expressions of bigotry, in such a public forum, license behavior that might otherwise be kept in check. In just the last few weeks, we have seen high school students taunting racially diverse sports teams with chants of ‘Trump, Trump’; we have seen young people of color being jeered at, pushed and shoved, and ejected from spaces in which Trump is speaking; and we have seen the Ku Klux Klan emerge as a topic of debate on cable news channels. Such phenomena effect relations between citizens: they effect who is welcome in which spaces; whose voices are granted a hearing; whose histories are taken to matter; and against whom violence can be inflicted. Saying it out loud has effects.

Surely, though, we can imagine a supporter of Millian liberalism declaring, having these ideas out in the open allows them to be countered with reasoned argument. Won’t the cleansing power of ‘more speech’ win out in the end? I think such optimism is deeply misplaced. These are not moves in a rational argument that can be countered with evidence. It’s impossible to counter falsehoods if those who espouse them aren’t listening; and it’s impossible to counter falsehoods if those who espouse them have already decided that any attempt at countering them is further evidence of untrustworthiness on the part of their interlocutor.

What, then, of the second refrain? I’m assuming here that not everyone who expresses such sentiments believes that a Trump presidency will improve their situation—the call to ‘burn it to the ground’ seems primarily aimed at harming the political elite, rather than benefiting oneself. I see two possible ways to interpret such attitudes. On the one hand, such attitudes could be understood in light of psychological experiments that show participants’ willingness to pay to punish non-cooperators (such as the ‘ultimatum game’, or third-party observers to prisoners dilemmas). People, it seems, are willing to forego a good for themselves, in order to inflict punishment on someone who has not behaved fairly. At the political level, then, it may be that some citizens are willing to forego the benefits of democratic institutions in order to punish the political elite who have behaved in ways that they deem unfair. An alternative interpretation is that some citizens do not see democratic institutions as bringing any benefits at all. There is nothing to lose, so we may as well burn it all to the ground. Whichever interpretation we go with, such sentiments suggest a radically disenfranchised citizenry. When sufficient numbers of people have come to feel so poorly served by democratic institutions that they are prepared to see them crumble, democracy is in a precarious position.

Gina Schouten — Does it Matter that Clinton Is a Woman?

I have been feeling the Bern something fierce. But should my enthusiasm for Bernie be tempered somehow by the fact that his opponent is a woman? Madeleine Albright seemed to think so when she remarked recently that “there’s a special place in hell” for women who don’t help each other. I confess to having felt indignant. To be fair, she said it with a twinkle; perhaps she was more teasing than admonishing. And she quickly walked it back. But there is surely something here worth thinking hard about. Does the fact that Clinton is a woman give us reason to support her? Notice, first, that I have already weakened the position under consideration. Albright’s quip suggested that we have a decisive reason to support Clinton because she is a woman, but any obligation to support women in pursuit of their projects cannot be a decisive one—we should not have supported Carly Fiorina, after all. The weaker position I want to consider is initially more plausible: Does the fact that Clinton is a woman give us any reason at all to support her candidacy? That is, does it tell in favor of supporting her candidacy?

We might have reason to support those who have historically received unfairly small investments or support in the pursuit of their projects. But Clinton is in a zero-sum competition. While, on average, women have received less support in pursuit of their projects than have men, gender is only one aspect of identity, and other aspects also influence the investments of support one receives. We have, as yet, no case either that Clinton has received unfairly little support all-things-considered, or that she has received less support than her competitor. Alternatively, women might have reason to support Clinton based on some special relationship, just as parents have special obligations of support toward their children. But what could this relationship be? It cannot be the mere fact of shared gender identity. Shared gender identity might give us reason to pursue some special relationship—for example, if it makes it likelier that we will have some shared values. And that relationship might subsequently generate reasons for me to support her projects. But mere social similarity seems not directly to generate such reasons.

There is another approach we might take, which begins with the role in question, rather than with the woman herself. It might be that, for any role of authority or prestige, we have some reason to support some woman in her endeavor to occupy that role. There are two routes by which such a reason might arise. First, we have reason to prefer that roles be filled by those most competent to do so. We might think that, given prevailing social norms and trends, women are on average likelier than men to perform excellently in certain roles—because they would have to be more qualified to be perceived as equally qualified, for example, or because their gender equips them to represent some set of interests that receives inadequate attention under the status quo. Secondly, we might have reason to promote women for certain roles in order to promote gender justice: By paving the way for future women occupants and by challenging gendered stereotypes about fitness for the role, promoting a woman here and now might expand women’s access to positions of prestige and authority moving forward.

Albright’s quip suggested that, for any particular person, the fact that that person is a woman gives other women reason to promote her projects. This is implausible. But something in the neighborhood might be right: For any particular role of power or prestige, given existing gender imbalances, we have some reason to support women in pursuit of that role. Notice, though, that these are reasons for men no less than for women. Men should want positions to be filled by those most capable of filling them well, and so should care if circumstances obtain such that members of underrepresented groups are likely on average to be particularly capable. Men also should want a more gender just society, and so have reason to support the pursuits of women to occupy positions of power and prestige if doing so promotes gender justice. Notice too that these reasons are contingent. Likelihood of better performance gives us reason to support women only if the women pursuing the position are really likelier to perform better. Whether they are depends on more than gender. Similarly, whether supporting Clinton will promote gender justice depends not just on her occupying the position as a woman but on what she will do with it once there. Finally, these reasons are defeasible. Even if successfully supporting a qualified woman in her pursuits will in fact promote gender justice, we have reasons also to promote other social ends, and reasons of gender justice might give way to other considerations.

None of this is to deny that there are non-gender related reasons to support Clinton. Nor is it to criticize Albright. (Sometimes, you really should just luxuriate in a good hell joke!) But there is something behind her words that was not a joke. It is worth using the tools of philosophical excavation to bring it to light, examine it, and think what should be done with it.

What the hell kind of “misinformation” and “prejudice” is Sanders supposed to be playing to? Good grief.

Sanders lacks basic knowledge of economics and how we know human beings operate given various incentive structures. His heart may be in the right place, but he is appealing to the same kind of ignorance as Trump.

And this basic knowledge is??? I see a lot of people throwing this around, but have yet to see any substantive counters. Reminds me of freshman saying “communism works in theory, but not in practice.”

He is against multinational trade agreements. Trade agreements are something every mainstream economist agrees is good for the economy.

If they make it even easier for multinational corporations to shift production to the countries where the workers are paid the least?

That’s not what these trads are predicated on at all.

One of the main focusses of this agreement is that worker protections aren’t high enough!

It is true that mainstream economists believe that open trade is generally good for economies (however we should not be entirely uncritical of economics, of all sciences). But some trade deals are better than others (and I doubt Sanders is against free trade wholesale).

A fairly mainstream economist: http://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/jan/10/in-2016-better-trade-agreements-trans-pacific-partnership

There is a further question of when things are good for “economies,” *who* in those economies it is good for (and to what good).

Why do you think he’s against multinational trade agreements? To my knowledge, he isn’t. He has, of course, opposed NAFTA, CAFTA, TPP, etc., and he has raised concerns regarding human rights violations enabled by certain free trade agreements, but he has also said that our trade policies ought to be reworked so as to enable fair trade — if you wanted to get rid of something entirely, it would be odd to say you want to rework it.

In any case, this is the most extensive speech he’s given on the topic that I know of, from the senate floor in 2011: http://www.progressive.org/news/2011/10/170238/bernie-sanders-denounces-free-trade-pacts

Not exactly so. Many economists believe NAFTA to be largely a failure. The Obama administration admitted it clearly when rolling out the TPP. In fact, just google “NAFTA after 20 years” and see the multiple results from both sides of the issue on the front page.

What “basic knowledge” are you talking about?

Chris, I would be surprised if these folks were supporting Sanders out of ignorance of economics: https://berniesanders.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Wall-St-Letter-1.pdf

Surely people can disagree, think they’re mistaken, but to put that disagreement on a par with support for Trump?

Thanks for that, Kathryn, I hadn’t seen it. It seems that folks signing the proposal are in favor of two things: (1) “busting up the big banks,” and (2) requiring a formal separation between investment and commercial banks. Those aren’t the sorts of things I was referring to when I said that Sanders’s populist rhetoric simply appeals to the economic ignorance of the electorate. I’m thinking of the sounds bites that are getting most of his supporters excited: “free” education, “free” healthcare, some type of Robin Hood tax system that goes after the “one percent” (whoever those are), etc.

Most Americans in general (including Sanders supporters) have no idea what the distinction is between an investment bank and a commercial bank, never mind if the size of certain banks pose a systemic risk to the economy. Most don’t understand basic accounting; don’t understand simple concepts like supply and demand (“We want Uber but no surge pricing!” “Raise the minimum wage and decrease unemployment!”); don’t understand the role incentives play in motivating decision-making; don’t understand that most regulatory laws disguised as, for example, consumer protection, are really just examples of corporate rent-seeking. This stuff is basic.

Sanders’s success can be traced to this ignorance. In the same way, Trump’s success can be traced to the ignorance: ignorance of the role free trade plays in making the lives of poor people better; ignorance (or hatred) of people of other ethnicities, religious preferences, or cultural backgrounds; ignorance of America’s place in the world (sorry, Donald, we’re still great by pretty much any measure); and so forth. The difference I see between the two is that I don’t think Sanders is acting nefariously and intentionally appealing to ignorance to try to win an election.

To be clear: I am not claiming that *all* of Sanders’s supporters are economically ignorant or *all* of Trumps supporters are bigots. Rather, what has allowed them both to be successful is they have been able to appeal to the prejudices of very large groups of people, prejudices that are based in ignorance.

Is there evidence that Sanders supporters are less ignorant on these issues than supporters of other candidates? If not, then their ignorance isn’t a good explanation of Sanders’s success at this stage.

Also, I don’t get your implication (through scare quotes and phrases like “some kind of”) that progressive taxation, universal health care, college without tuition, or higher taxes on the top 1% of earners are obscure concepts. The latter is just an extension of current tax policy. The others exist in various forms in various countries. If you mean, e.g. that the government would still have to use tax revenue to pay for health care under Sanders’s health care proposal or for college under his no tuition proposal–I’ll bet you Sanders supporters aren’t especially ignorant on this point.

As for the supposed conflict between raising the minimum wage and pursuing higher employment–this is definitely not “basic stuff”. Yes, there is a simple (simplistic?) supply and demand analysis that says that minimum wages reduce employment. But the empirical literature on minimum wages is divided on whether this has been borne out.

Finally, “prejudice” is one way of describing what Sanders is appealing to. “Basic orientation” or “values” or “conception of justice” are better ways.

“Basic orientation” or “values” or “conception of justice” are better ways. ”

They’re not better or worse – they’re just equally biased ways to say the same thing. All these things mean the same thing in practice whether you chose to romanticize it or be blunt about it.

“Is there evidence that Sanders supporters are less ignorant on these issues than supporters of other candidates?”

I don’t know, but even if we just remember that political ignorance applies to the media voter, it’s quite clear that Sanders and Trump rhetorically appeal to this type of ignorance. Every complex issue is reducible to simple binary of right/wrong – in the case of Sanders his entire platform is built on the notion of evil elites/corporations running the world and ruining America.

That said it’s true that all politicians are populist to an extent. However, Trump and Sanders exemplify what it means by the manner in which they speak, campaign, frame the issues and even what their ‘solutions’ are.

The people whose incomes are higher than those of at least 99% of the US population. Hence the name “one percent.” It’s fairly easy to devise a tax system that raises more money from these people; the technical term for that is “progressive taxation,” not “Robin Hood tax system.”

Have you looked at the empirical research on the effect of the minimum wage at all? The question of whether increasing the minimum wage increases unemployment is unsettled to say the least. It’s certainly not “basic.”

Really, you’re not making a convincing case that Sanders supporters are ignorant.

“It’s fairly easy to devise a tax system that raises more money from these people”

It really isn’t easy. If it were easy it wouldn’t be a problem because everyone agrees that people, multinational corporations etc should pay their ‘fair share.’

“The question of whether increasing the minimum wage increases unemployment is unsettled to say the least.”

It’s actually pretty well established that above certain thresholds and rates of introduction it is harmful to employment levels. The way Sanders is proposing it would be harmful because he wants to do it wholesale at the Federal level, ignoring microlevel economic differences at the state level. It’s reckless economic populism designed to appeal to misinformation and preconceived notions of what would be ‘justice’ or helpful.

Not everyone agrees that the top earners should pay more in tax. That’s why the Republicans have cut taxes for the top earners when they’ve held power, and continue to propose cutting taxes for the top earners.

Look at taxfoundation.org for analyses of the various candidates’ tax plans. Sanders’s plan raises a lot more money from the top 1% of earners, the 99% to 100% row on the distributional chart. (And from everyone else too, since his plan is to raise taxes to pay for services, but it raises the most from the top 1%.) Clinton’s raises somewhat more money from the top 1% without raising taxes below that at all. The Republican candidates’ plans lower taxes on the top 1%.

Honestly, I don’t know how we’re at the point where anyone can claim that it’s obscure what the 1% is or whether a candidate can propose a tax plan that raises more money from them. It’s not difficult to establish.

Sanders’s proposals have been criticized by experts like Alan Krueger who say that we don’t know what will happen if the minimum wage goes up to $15. This is the opposite of saying “It’s pretty well established” that the effects will be harmful.

By all means criticize Sanders’s proposals with evidence–I don’t think they’re beyond criticism. But we have to have a legitimate debate based on the evidence. We can’t have that debate if people are going to pretend that Sanders’s policy proposals are in any way parallel to the things Trump is doing. They just aren’t.

“It’s fairly easy to devise a tax system that raises more money from these people”

Raising marginal tax rates is not synonymous with generating more tax revenue, because the amount of income earned and thus revenue collected is not independent of the rate of taxation. It’s entirely possible to raise tax rates to a level where the effect on total revenue is negative. Where that point is and whether we’re at or near the point of negative marginal returns is an empirical matter, but it’s by no means simple or settled.

But Chris, we could quite plausibly hypothesize the same thing about supporters of free-trade. We could say that they’re ignorant of the the relationship between the way trade is liberalized in theory versus the limitations of “free-trade” policies in actually creating free-trade in practice. Is the average citizen supporter of free-trade thinking about the role of the IMF trade liberalization agreements in the destruction of 2010 Haitian earthquake, or remembering that even where “free trade” agreements are put in place, their outcomes will be shaped by other non-free-market practices like the agricultural subsidies that put American rice farmers at an advantage — subsidies that the tariffs were helping to equalize before they were removed? Are they familiar with the human rights impact of IMF agreements at all?

It’s one thing to say that trade liberalization would be the economically best route to take, and another to say that implementing a few free-trade agreements, against the backdrop of a not-truly-free-market-economy, is the economically best route to take. One might think that folks who support liberalizing policies because they understand the value of free-markets generally are doing so out of ignorance of certain political facts.

“Sanders lacks basic knowledge of economics and how we know human beings operate given various incentive structures.”

Even if I were to grant this, it is not the same kind of appeal to ignorance as Trump; it is the same kind of appeal to ignorance as the vast majority of the Republican party, who demonstrated their lack of basic economic knowledge by encouraging austerity during a recession when we were in a liquidity trap. One could go on.

Some of Sanders’s proposals have been convincingly criticized as underimplemented and resting on unrealistic assumptions, but again, this is at least equally true of every Republican candidate and the entire party; search for “Paul Ryan magic asterisk.”

Really, this is the most unserious sort of both-sides-do-it moral equivalence. “Trump stirs up racist hate, encourages violence against protesters, urges his followers to attack Bernie Sanders rallies, and boasts about how enthusiastically he will commit crimes against humanity. Sanders has some unrealistic policy proposals (like the “mainstream” Republicans) and criticizes some free trade agreements. They are just the same!”

Among other things, Sanders is–from a mainstream economist perspective–wrong about international trade and the overall effects of immigration on domestic wages and welfare. He’s also spreading misinformation about what the Scandinavian states are like–they are generally free market welfare states rather than democratic socialist states.

Sanders is stipulating that is what he means by democratic socialism. He is happy with the free market role in Scandinavian states (and Germany and the UK and others). You may disagree with his terminology, but he is not spreading misinformation about the nature of those countries and their social programs that he applauds.

I realize many philosophers like Sanders, though that just makes me worried about the philosophy profession. (When I hear philosophers talk about economic issues, it reminds me of my four-year-old son saying, “Whee, bubbles!”, but without the sweetness.)

But two points:

1. Even if Sanders simply were using the words in a strange, incorrect way, using the term “socialism” to mean “free market welfare states a la Denmark”, he would still be spreading misinformation, because most people do not interpret him that way.

2. More importantly, Sanders do not actually appear the US become like Denmark. He’s rather advocating a number of economically illiterate policies that Denmark, Finland, etc., wisely reject.

Oops, second to last sentence got messed up. I meant Sanders is not in generally advocating policies that bring us closer to those of Denmark. A good way to put it is that compared to the US, Denmark has a better functioning and more extensive social insurance state, but a less obtrusive and less extensive administrative state. Bernie is advocating vastly expanding both the social insurance and administrative roles of the US government.

Calling Scandinavian states ‘socialist’ isn’t strange or incorrect; it’s standard in the American dialect, according to which public provision of health care and redistribution of wealth through taxation count as socialism. That there exist homonymous technical terms in academic debates doesn’t impugn the use of the ordinary American meaning by politicians.

The stuff about administrative vs. insurance state is very vague. But I’m guessing you’re talking at least in part about the lesser amount of regulation on business in most Scandinavian countries. But your criticism is a silly one for simpler reasons. Obviously, Sanders isn’t advocating every policy from those countries. It doesn’t follow that he’s “not in general advocating policies that bring us closer to those of Denmark”. Zero tuition and universal public health care would be huge changes for the USA and would outweigh changes on the administrative side that would move us away from Denmark.

As for the claim about Denmark being more of an “insurance state”, I don’t know what this means–I’ve never heard this term before and Google isn’t turning anything up. Some of the continental European states are sometimes described in these kinds of terms, for their use of, e.g., mandatory participation in insurance programs as a way of providing social programs. But the Scandinavian systems, generally described as “Social Democratic”, are generally contrasted with this. Scandinavian countries use either the Beveridge model or single payer model for health care, e.g.

In addition to what Chris Surprenant mentioned, Sanders’s success is also arguably in part due to semi-conspiratorial prejudices against wealthy people (especially people in finance) and so-called “establishment” politicians that seem to be pretty common.

What “semi-conspiratorial prejudices” are those? The recognition that executives now take home 319x the average worker pay, while in the 1960s, the disparity was only 30x?

I have in mind more the idea that corrupt politicians and wealthy people are in cahoots to screw over regular people in order to benefit themselves. There is, of course, no doubt that regular people are worse off (relatively speaking) now than before.

Are you really implying that this is false or unfounded? It is literally fact.

The fact that regular people are worse off now than before is not an inevitable consequence of history. It is the result of policies that politicians (corrupt or not) vote for. Not surprisingly, wealthy people (Kochs anyone?) lobby politicians to vote for these policies. In what world is this anything but politicians and wealthy people screwing over regular people in order to benefit themselves?

Whether it’s inevitable is unclear to me. It seems to me the most important problem is that a huge number jobs are disappearing or have already disappeared due to automation, outsourcing, or irrelevance. Moreover, the jobs that have taken their place are too scarce and, more importantly, require more intelligence and specialized ability than the majority of people possess. This isn’t just a problem in the US, by the way; it’s a huge problem in the entire developed world, including the social democracies in Europe that Sanders admires.

Perhaps certain policies exacerbated the situation in the US; perhaps some of this could have been slowed down with sufficiently protectionist laws. But then such laws have their own costs.

Killmister writes: “Surely, though, we can imagine a supporter of Millian liberalism declaring, having these ideas out in the open allows them to be countered with reasoned argument. Won’t the cleansing power of ‘more speech’ win out in the end? I think such optimism is deeply misplaced. These are not moves in a rational argument that can be countered with evidence. It’s impossible to counter falsehoods if those who espouse them aren’t listening; and it’s impossible to counter falsehoods if those who espouse them have already decided that any attempt at countering them is further evidence of untrustworthiness on the part of their interlocutor.”

Two questions/objections:

1. How do you know that Trump supporters aren’t listening? How do you know that they have more of a confirmation bias than anyone else? I strongly support Sanders myself, but find just as much confirmation bias on the left as on the right.

2. Can the “the cleansing power of more speech” be so quickly dismissed? According to Sperber and Mercier (https://sites.google.com/site/hugomercier/theargumentativetheoryofreasoning), people reason better in groups (that include people with the opposite view) than alone, precisely because when people reason alone, there is nothing to keep their confirmation bias in check.

Forgive me for asking; I’m new to Daily Nous: do you allow subscribers like me to post, for example, the individual pieces from “Philosophers On the 2016 U.S. Presidential Race” on Facebook?

Thanks for asking. I suppose that’s fine. Including a link back to the original post would be appreciated.

Thank you, Justin W. Will do.

The idea of voting Trump over Clinton to ‘burn it to the ground’ isn’t just directed towards political elites. It’s directed at every unjust cog in the system be it law enforcement, health care, economic inequality, education and so forth. It is the literal desire to see the USA and it’s institutions burning to the ground. The social upheaval in the 60/70’s will seem like a dress rehearsal to what will happen if Trump wins the general election, it might even happen with a Clinton win if she doesn’t do anything substantial to fix the institutional problems the status quo perpetuates.

The analysis by Killmister fails to include a third possible reason for a Bernie supporter (such as myself) voting for Trump in the general should Bernie not become the nominee. This third reason has nothing whatsoever to do with punishment. It may well be held that the ONLY reason that Bernie sanders is not the nominee is simply because things have not gotten bad enough yet to cause a reaction sufficient to elect a progressive such as Bernie Sanders. This being the case, then the most efficient reaction is to vote for Trump because no one will make things worse faster than him: four years of trump vs. eight years of Billary.

What could possibly go wrong?

Exact same stuff only quicker.

For those that appreciate the deeply researched and well thought out five word response, please allow me to rephrase: Lobbyists are writing our legislation, the President is assassinating American citizens, and the Supreme Court now allows billions of special interest dollars to corrupt the election of every single public official in our country: their decision boils down exactly to your five word response. What is left?

You’re probably right; it’s not as if the president has access to nuclear weapons or anything silly like that.

From the article, Alexander Guerrero — Update the ‘Old Technology’ of Elections

— “Sanders, with decades of principled droning on behind him, would like to institute democratic socialism to rival Scandinavia.”

It’s amazing to me, when so many people dismiss so condescendingly one of the precious few sane, honest and passionate voices of decades. He’s just “droning on”. No, Bernie’s contemporaries were just droning on, and not even anything principled, all too often something corrupt, bigoted and/or inane.

It saddens me that people have failed to listen to Bernie, and then erect stereotypical straw men as though it’s his fault. Bernie promotes some policies, because that’s what you have to do in an election or nobody understands you at all. But if you listen more carefully, he’s completely transparent about something nobody else is even discussing, that is a meta-statement on politics, policy and his job as president: he points out that Obama was largely ineffective because he dismissed the popular support that elected him to office, without which Obama could not challenge the establishment powers. While that assessment may be too charitable, Sanders is frank that he would be useless in office, UNLESS A POLITICAL REVOLUTION OF MANY MILLIONS OF PEOPLE CONTINUE TO STAND BEHIND HIM. And that revolution is his entire purpose for becoming president. It also directly implies that Sanders’ own policy agenda is nothing he expects he could dictate, it is only his suggestion, and anything that could be achieved would be purely a product of the continued will of the people. EG If people don’t want universal health care, then Sanders won’t be able to achieve it. But the people do want it, 58% total as of Dec 2015, so campaigning for it can’t be construed as going against the popular will, and it would save a huge amount of money if it can be achieved.

Trump is a megalomaniac so delusional he thinks the president is a king and dictator, and he can singlehandedly strong-arm the nation Great Again (“Make America great again” was Reagan’s slogan too).

Clinton is the establishment’s darling, a woman who will proudly serve the top 1%, because that is the America she belongs to and who she perceives. She will be very effective, at doing exactly what the billionaires dictate.

Sanders says we need a revolution, because the billionaires who currently totally control and own the country, are destroying it from within. He is right, honest, and hopes We The People take back the power and fix it, because he knows only we can.

Thanks for your comment, exploderator (if that is your real name).

I in no way intended to dismiss Bernie Sanders (although I see there appears to be a bat signal or something).

Many of my best friends have spent decades droning on about values and justice. My point was not that he should be dismissed, but that he has been dismissed for almost 30 years. You could turn on CSPAN or CSPAN2 (or, later, CSPAN3!) in 1998 and see him making pretty much the same speeches he is making now. That consistency is of course admirable. As are his ideas! (Some of them, anyway.) But it’s still amazing that *now* people are responding to them at an unprecedented scale. It’s like all of a sudden Sisyphus gets to the top, gives it one last push, and the boulder finally sticks.

Maybe you were reacting to “droning on”–but it’s hardly as if he’s recently become more charismatic and engaging. Were you watching him on CSPAN in the 1990s? Was anyone? The only person who has given more unlistened-to speeches about socialist values than Bernie Sanders is Fidel Castro.

Alexander, Thank you for the warm and thoughtful reply, and sorry for my silly anonymous name. I promise there is a very sincere person behind the keyboard 🙂

I’m sorry that my reply here is long, but I think I have formulated an important point that is worth your time to read, and I submit this with respect for your time and energy.

I have to fully admit my own hypersensitivity with respect to interpreting “droning on” as having a more negative connotation than you intended. My reason begins simply enough: there has been a widespread and systematic negativity and dismissal of Bernie in the mainstream media, that I feel must be rejected and countered at every turn. One simple example, a headline where Sanders and Trump win the primaries for a state, gets covered with something like “Big win for Trump, Sanders has strong showing.” They just can’t bring themselves to say he won, there’s a sickening reluctance. Your “droning on” sounded too similar and I pounced. Clinton’s main approach to Sanders has been nauseating condescension, while transparently and desperately parroting his points to pander to a base that is fast progressing beyond her (the fact she’s scrambling now just shows how deeply she dismissed Occupy at the time and ever since, and one can have little doubt that speaks to where she’s really coming from). This all becomes a frustrating theme for anyone who’s been waiting for sane, honest and intelligent political discourse for decades. When someone with substance and integrity like Sanders finally breaks through the wall of corruption and substantially re-writes the political discourse of a nation, only to be systematically sneered at by the establishment, my reaction is to chastise the dismissal on principle.

The principle I think matters most is this: the dismissal of Sanders fits a fundamental human social behavior pattern that must be overcome, where people are granted the right to speak based on their social status or ranking within the social hierarchy, and are dismissed summarily and with prejudice if they are deemed unworthy, regardless of what they say. This basic pattern is what allows a megalomaniac jackass like Trump to steal an entire party (albeit the Republicans were well primed because they have long played on the conservative attitude of strong respect for authority). This pattern is what allows Clinton to transparently lie and pander, and not be shredded by the media (the public is starting to notice). This pattern has enabled decades of public political discourse so vapid and so dishonest, that entire nations can barely think any more, and democracies are being systematically disassembled by the top 1% wealthy while the other 99% stumble around in hypnotized befuddlement and ignorance, largely unable to muster a coherent sentence in reply (even when they do, they don’t have sufficient rank to speak). We need to bring actual ideas back into the public political discourse, and profoundly shame anyone who can’t speak deeply and truthfully to that discourse, no matter how much money they have, no matter how many media outlets pander to them, no matter how many years they have or have not been in power, no matter what their social status is. Democracy is a fraudulent promise if the public can’t deal with reality and vote accordingly, it becomes a contest of acted personality and media spectacle where the richest production usually wins. Trump, the seasoned performer.

As has happened all throughout human history, societies get torn apart because power becomes increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few, and corruption takes over. No system of politics or economics is yet immune. This concentration happens when we accept social status and power as real, and respect it and obey it instead of dealing with actual issues. When the fundamental underlying emotional messaging is that Sanders is a beta, an untouchable, that needs to be dismissed and ignored and ridiculed for daring to bother the “real adults” and superiors, we need to fight on principle, and do everything we can to counter that message, by carefully referring to Sanders as a respectable equal, addressing the ideas, and being careful not to contribute to the dismissive tone. Otherwise we pave the same road that monsters like Trump are currently bulldozing, and that establishment representatives like Clinton expect to skate down freely and unhindered.

Thanks for your thoughtful and eloquent continued response. I agree with almost everything you say. For my characterization of both Trump and Sanders, I was more drawing attention to their public perception, rather than stating my own reaction to them.

But I certainly agree with this: “where people are granted the right to speak based on their social status or ranking within the social hierarchy, and are dismissed summarily and with prejudice if they are deemed unworthy, regardless of what they say.” Indeed, as one of the very few people who argue for randomly selecting people by lottery to have those people serve as our political representatives, I am more committed than most to think that every person in the political community has something to contribute to political decisionmaking.

I should have said, “agree with [the quoted bit] as a real problem”!

I’ll go along with your idea of a lottery, as long as the tickets require a post-secondary degree or diploma, thus indicating at least a basic ability and desire to read and develop some skills. Anything that would break the current corruption would be a vast improvement on what we have now.

Alexander, I was actually watching him on C-SPAN in the 90s. I just couldn’t vote yet then.

I definitely saw him a few times, too. But it mostly made me think: “geez, Vermont must be *really* liberal compared to most of the U.S.” rather than “this guy will be a serious candidate for president in 20 years!”

I am woman legislator from Zimbabwe in Africa. I am shocked and disappointed that women of substance like Gin Schouten would condemna fellow woman or think twice before supporting a fellow woman. As women legislators woman are judged with a hard yard stick. We have to work four times more than our male counterparts. If Hillary loses this presidential primary America will not see an attempt by a woman at the presidency. I now believe that 90% of American women were either psychologically abused by their father’s, brothers or boyfriends. How do you explain the fact that young girls boast about voting for men and because they believe that men are more capable than women. Shame on the mother’s, women and sisters of America. Please visit the nordic countries to learn one or two things about women empowerment and gender equity and equality. Thank you. Proudly a woman.

I’d vote for Elisabeth Warren instead of Bernie if she was in the race. The other implications you mentioned I personally cannot comment on because I am a guy. But I would like to see an American female perspective on what you just said.

I’m an American woman, and feminist, and I don’t think the fact that HIllary is a woman gives us, in itself, any positive reason to support her candidacy. I do think women are disadvantaged in American politics, and I do think that if Bernie were a woman there would be very little chance he’d be taken seriously, and I do think that if Hillary were a man, she’d have more support than she does — but while that someone has been subject to sexist treatment, or that they would be treated differently on the basis of their gender certainly gives us reason to break down the systems of injustice that result in differential treatment, I do not think it amounts, necessarily, to reason to support that particular candidate over others (Sarah Palin was treated in horrifically sexist ways — and that was wrong, it should not have happened, but it does not mean I would have ever voted for her). It should be unsurprising, I think, that even thoughtful feminists will sometimes think that a particular man is better positioned to represent women’s interests, and for exactly the same reasons people will think Hillary is up against a sexist political system in the first place; where patriarchal social structures are in play, women will have to work harder to show that they belong, to succeed, and sometimes that will mean (at least) acting as if one buys into the rules of the game that hold them back.

I thought Schouten’s contribution to this post was excellent.

I was so puzzled by Ruth Labode’s comment that I went back and re-read Gina Schouten’s piece. There is not one line that condemns women in any way. On the contrary, Schouten’s seems the most charitable and cautious of all the entries. The closest thing I can find to condemnation of a woman is when she says, “Similarly, whether supporting Clinton will promote gender justice depends not just on her occupying the position as a woman but on what she will do with it once there.” If raising the possibility that Clinton will not promote gender justice is condemnatory, then it is a condemnation true of all candidates of all genders.

Thinking twice is Schouten’s job, so I thank Gina Schouten for this philosophical reflection. I have been debating exactly the main question she raises for months, whether being a woman counts in Clinton’s favor in any way for my vote. I now realize after reading Schouten that I am inclined to what she calls the role-related reason. I do believe that a woman president now will make future women’s candidacies more likely to be taken seriously.

Hello, Ruth!

I think there’s a chance you might have misunderstood Schouten’s position.

Schouten isn’t “condemning fellow women” or saying that we ought not support women.

On the contrary, she sheds light on some plausible reasons we *should* support a woman for the sake of her being a woman. She mentions that they are probably, at least generally, *more* competent than their male counterparts, as they are judged more harshly and must work harder than their male counterparts for the same recognition. I’m sure you probably experience some of this as a legislator in Zimbabwe. She also mentions that supporting a woman could challenge gender stereotypes and “pave the way” for future woman occupants, thereby promoting justice. These are good things!

Her position is a more modest one: that while there may be, indeed, many good reasons to support a woman solely because of her womanhood, these reasons are dependent on things outside of gender, in that in order to find out whether they are true, we need more information than *just* their gender. Finally, there are *many* reasons to vote for a candidate, and it is possible that a collection of more pressing “social ends” or objectives/considerations could move the social end of gender justice, for example, to the background.

Unfortunately nothing about being a woman has stopped Hillary Clinton from being a dishonest and horribly corrupt tool of the billionaire elites, of which she is effectively a member. Her gender is sadly irrelevant in the face of her insurmountable disqualifications. Meanwhile there are many superbly qualified women who are not corrupt at all, but who did not run for office, probably because the political party system in the USA is so desperately corrupt and broken that it is almost impossible to run a credible campaign if you are not backed by huge amounts of money from big business. That is all a real shame. There are a very large number of women in the USA voting for Bernie Sanders exactly because Clinton is corrupt, while Sanders is a genuinely honest, compassionate progressive who very obviously treats all people as equals, and has fought for women’s and racial equality all his life. There every chance he will do more for women than Clinton, who will ultimately serve business and nothing else.

The Republic under Assault

Joseph Coleman

The Liberal-Progressives threaten to usurp our freedoms and natural rights as guaranteed by the Constitution. Progressives view our constitution a kind of living constitution that continually changes to fit contemporary issues and reject the Founders intent of equal rights for all Americans and special privileges for none. These progressives believe that the government is obligated to tax the haves and give to the have nots to achieve what they perceive as an equal society. In my view this is not far removed from Lenin’s dictate a hundred years ago of “from each according to his ability and to each according to his needs.” We all see that this progressive thinking implies special privileges to certain constituencies at the expense of others. This belief is not what the Founders intended.

According to the American Founders, the purpose of just government is to secure the natural rights of its citizens, such as the rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. By contrast, the consensus among much of today’s political elite is that government exists to provide benefits and favors for designated constituencies. This new view—which underlies much of contemporary American public policy—constitutes a rejection of the Founders’ policy of equal rights for all Americans and special privileges for none.

The American Founders wrote a Constitution that established a government limited in size and scope, whose central purpose was to secure the natural rights of all Americans. By contrast, early Progressives rejected the notion of fixed limits on government, and their political descendants continue today to seek an ever-larger role for the federal bureaucracy in American life. In light of this fundamental and ongoing disagreement over the purpose of government, I believe the Republican candidates will consider contemporary public policy issues from a constitutional viewpoint. We have already witnessed how the Obama Administration acts in an extra-constitutional or unconstitutional manner in order to force his Liberal-progressive agenda without regard to the will of the people. Democratic front runner Hilleary Clinton publicly stated her intention, if elected, to continue Obama’s policies. We the people must go to the polls and speak to this unconstitutional Liberal-progressive style of government that Obama further designed to make us a socialist state and strip our freedoms guaranteed by the constitution. We must act in the voting booth to preserve our Republic.

Stuff like this always gives me a good chuckle. Constitutional law and political philosophy are simple, stupid! Just do what the founders intended for every future generation of Americans in perpetuity! (Which we can easily know, because I see dead people.) They may have been mere mortals like us, but that doesn’t mean they weren’t infallible paragons of justice who knew perfectly what justice demands in any given case and time. Which is, rather conveniently, why it would be unjust for present US citizens to refuse to be forced to respect the intentions behind an agreement forged in response to the political and economic particulars of a bunch of British subjects that predates the US itself. Or, maybe it’s because they had a direct, toll-free line to God, who clued them in on the ‘natural’ rights He gave us using His limitless supernatural powers? Anyway, it’s not like anyone can seriously doubt that we have these fundamental, inalienable rights as a matter of divine command or whatever, right? Something, something… Obama! Socialist! Boo!