Philosophy Citation Practices Revisited

You may recall that earlier this year, in a guest post, Marcus Arvan decried philosophers’ reading and citation habits. Now, Moti Mizrahi has a post up at The Philosophers’ Cocoon with data showing that philosophy articles, on average, contain fewer than five cites per article [correction, thanks to npa in the comments:] are cited less than five times:

Additionally, Mizrahi says that other data suggest a downward trend in the percentage of philosophy articles that get cited, though it is unclear (a) whether that is really happening, or whether the data simply reflects that newer articles are, well, newer, and (b) even if it is happening, it may be consistent with an increase in the total amount of citations, and just a function of more articles being published nowadays than fifteen years ago.

See the post and discussion here.

I really don’t understand this either. Maybe it’s because I have some background in psychology but I can’t imagine writing an article without having at least as many citations as pages (normally 2-3 times as many). I know that some journals have a stated preference for fewer citations but I wonder how philosophical culture ended up this way.

Hey Justin, as Marcus pointed out over at the Cocoon, the graph doesn’t show anything about how many citations philosophy articles *contain*, it shows how many times philosophy articles are cited (by others).

Thank you. The news isn’t *as* bad, then.

I’m sorry to say that I think the news is very bad indeed, because it, plus the follow-up comments to Moti Mizrahi’s post, suggest that my many déjà vu experiences – of finding my arguments and analyses in other people’s papers without citation – is more typical than atypical. It might be useful to consider what professional pressures are promoting the regular violation of this very basic principle of intellectual integrity.

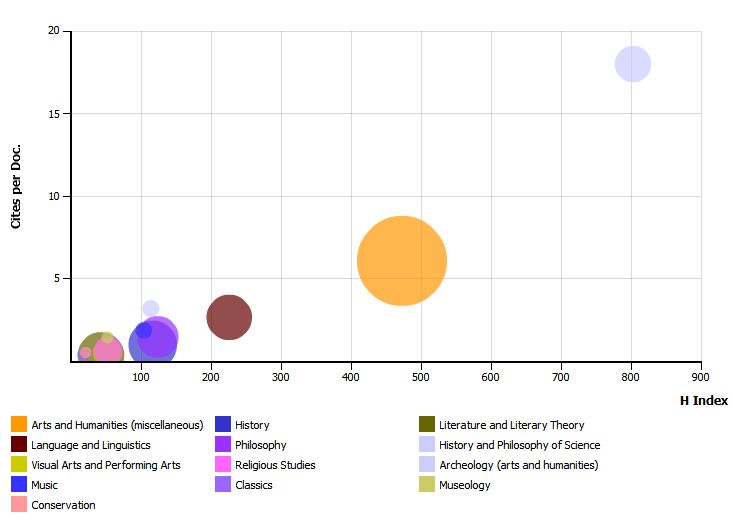

Clearly everyone should move into philosophy of science. The graph here (showing that the average number of citations in HPS is much higher than the philosophy average) confirms my anecdotal impression that we cite quite a lot more. Also, we have cookies.

The data set has a predominance of science journals, which explains the disproportionate number of HPS citations.

If that’s right, so much the better! I’d be delighted (though rather surprised) if HPS work is being cited extensively by scientists.

Assuming that citations of philosophy papers by papers that are not philosophy papers (and conversely) is negligible, doesn’t the number of citations per article have to be the same as the number of papers an average article cites?

The typical paper I read cites a lot more than five (philosophy) sources. Maybe something funny happens when we account for the number of citations that cite books rather than papers, and the number of papers cited in books. (But off hand that seems unlikely.)

The assumption may be wrong, I don’t know. Someone correct me if it is, please.

Jamie:

I assume there’s an issue about time. At The Philosopher’s Cocoon the first graph shows the percentage of articles with citations to them for the years 1996 to 2014, i.e. for articles published in 1996, then 1997, etc. As commenters point out there, the decline in that percentage shown on the graph, and worried about, is partly and even largely attributable to the fact that an article published in 2013 or 2014 hasn’t yet had much time to be cited, whereas one from 1996 has had a lot of time. Am I worried that a 2014 article of mine isn’t yet cited? Not at all. (An anecdote: checking on Google Scholar, an article of mine from 2005 reached its peak citations in 2013, eight years later. It takes time.)

I suspect some of the same thing is going on in the graph here. Assuming the database is the same as for the first graph, many of the more-than-5 citations you’re seeing when you read are to articles published before 1996; this will be most or close to all the citations in articles published in 1996, 1997, and 1998. But those citations don’t count in constructing the graph, because the cited articles aren’t in the 1996-2014 database. And citations the articles published in 2013 will receive after 2014 also don’t count, because they’re not in the database.

It’s true that the number of citations per article has to be the same as the number of papers an average article cites over a sufficiently long period of time, but it doesn’t have to be in a shorter period if you count only citations from articles in the period to articles in the period, as this exercise seems to do.

And HPS people shouldn’t be so cocky. One way to get a high score on the graph here is to cite mostly recent articles rather than older, more enduring ones, which happens in disciplines driven by short-lived fads. Not saying that about HPS but …

That must be the right explanation, Tom.

So now I’m not sure what to make of the data. It seems to show that on average we are citing about five recent papers, or maybe somewhat more given that the number of 1996-2014 papers cited in a 1996 paper is forced to be approximately zero. Does that mean we are citing too few recent papers?

I don’t understand a couple of things about the graph. First, I don’t quite get what the x-axis is supposed to be. It is labelled “h index.” Does philosophy’s position on that axis mean that in philosophy there are roughly 120 sources that have been cited 120 times or more? (Hard to believe that it is so few.) Secondly, what does the area of the circle mean? Is it meant to indicate how many papers there are in that area?

On a different point, Jamie Dreier’s point seems correct, unless there is some seriously distorting statistic that he (and I) are overlooking. The average number of citations in every paper should be the same as the average number of citations of every paper. However, this is compatible with there being a huge difference among papers with regard to how often they are cited. This suggests that where Moti Misrahi is NOT being cited, somebody else is. This is not uncommon: you might find that John Searle or Donald Davidson is cited in a catch-all kind of way for something that you feel you ought to have been cited for.

I’m not familiar with the concept of a catch-all kind of way citation. As I understand it, a proper citation includes author, title, date, publisher, place of publication if a book, or volume and issue number if a journal. If only an author’s name is included, this is not a citation but rather a mention.

By a catch-all citation, I meant a reflex citation to some philosopher who is well known in some area. For instance, if I am going to write on weakness of the will, say, I might cite Donald Davidson, even if it more relevant to the point I am making to cite somebody less well known. It’s a lazy practice, but partially accounts for the very wide variance among scholars with regard to numbers of citations.

Thanks, that helps. I’m still having trouble trying to imagine a situation in which it wouldn’t hurt my credibility as an author to cite a paper in which the topic I was writing on appeared, but the particular argument I meant to refer to either did not, or was mentioned only in passing, or only vaguely, or irrelevantly. I agree that it’s a lazy practice, but it seems to me also a self-defeating one: any reader who took my text seriously enough to follow up those citations would notice that I hadn’t taken them – or my readership – seriously enough to get their content right! Why would I undermine my own authority this way? Wouldn’t this practice have to be an expression of abject self-dislike? Or are my powers of imagination just maxing out (very possible)?

I also agree with Urstoff’s observation that straw man and “standard” arguments are often cooked up in order to avoid having to read the texts that state in what the real argument actually consists. It’s just too much trouble.

I don’t know if it hurts one’s credibility when one fails to cite. Isn’t that the whole problem? I often come across things like this. “Some have argued that meaning across theories is incommensurable (Kuhn 1962). This argument is tempered by . . . . (here a citation to Edwin Blogs would be appropriate, but it is omitted.)” This is a caricature, of course, but the fictional author of this travesty is using citation not primarily to give credit, but to guide the reader into thinking about Kuhn-style arguments.

I suppose it only hurts one’s credibility among those who know the literature well enough to know what texts should have been cited but weren’t. I don’t think it matters what ends your fictional author was trying to achieve by not citing correctly and accurately. The impression it leaves is one of inadequate knowledge of the literature. Of course anyone else in the subspecialty who is similarly afflicted is unlikely to notice this, whereas anyone who is not is unlikely to take the discussion, or the author, seriously (of course this fact may not necessarily hurt the author’s professional trajectory). I’m afraid I have to conclude that an author who does know the literature well enough to know the correct citation yet deliberately fails to make use of it expresses contempt for him/herself as well as for his/her readership, regardless of what his/her motives or purposes may be.

Sometimes I suspect that the lack of citations is often a way that the paper can attack a strawman rather than an argument actually made by someone somewhere. My suspicion is heightened further when someone “reconstructs” the “standard argument” for a position and then argues against that rather than an argument someone else explicitly made.

There was some discussion not long ago, here or elsewhere (I can’t remember, and so I can’t cite it!), about how citation choices reflect aspirations for group membership (cite the most prominent literature and nothing else to indicate the group you hope you’ll be identified with) or actual in-group membership (cite only your friends and existing interlocutors to show your status). Neither is justifiable, even if they are understandable.

On the other hand, in much of philosophy the issues being discussed are ones with such long histories and so many people writing on them that the very idea of “the literature” as a manageable body of readable and citable work explodes. And views do come in general family groupings, so it can be justifiable and helpful to present a kind of amalgam ‘standard argument’ for a view in order to attack it (or build on it for that matter), even if no particular person has offered it.

As I always support valid ways to streamline or reduce the research workload on principle, I wish I could agree with this argument, but I just can’t. Yes, “the literature” is starting to increase exponentially. But so are the 250-word abstracts of each article or book that constitutes the literature. Keywords also help to narrow and specify one’s search more precisely. All of this is much quicker and easier than (although not nearly as enjoyable as) going to the library and actually combing through its books and periodicals in order to find relevant sources – or ascertain that there are none – used to be.

As to whether the *particular* view one is discussing does, in fact, “come [within a] general family grouping,” that can only be determined after having first done this very basic research legwork, not in advance of it. To skip this essential first step is consign one’s analysis to vague generalities and empty gesturing; whereas if one has done that legwork, the “amalgam ‘standard argument'” is neither necessary nor helpful. So it doesn’t follow from these premises that “it can be justifiable and helpful to present a kind of amalgam ‘standard argument’ for a view in order to attack it (or build on it for that matter), even if no particular person has offered it.”

Having said that much, I do think there can be circumstances in which it *is* justified to “present a kind of amalgam ‘standard argument’ for a view in order to attack it …, even if no particular person has offered it.” The circumstances I know about are my own: I’d heard many Marxists argue in conversation that xenophobia could be explained in terms of unjust and unequal distributions of social goods. But I could find no published sources in which that claim was defended. So in the last chapter of Rationality and the Structure of the Self, I reconstructed that argument based solely on my memory of those discussions, without citations, because I’d found no sources to cite. But I can’t think of any circumstances in which it would be acceptable to fail to cite sources one knows exist. That’s called plagiarism. Nor can I think of any in which it would be acceptable not to try to find out whether or not any do exist. That’s called bad scholarship.

But look, the bottom line is this: If you devote your conference presentations and publications to attacking and/or building on views that nobody holds, you’re just asking for some unsympathetic colleague to demolish them by simply pointing that out: that no one says x, that it doesn’t work as an interpretation of y if you read her work, that it doesn’t address the claims that z actually makes, etc. Why do that? Why not just take the few extra hours, or days, to find out what your colleagues actually *do* think? It’s fun to learn things, and fun to come to grips with real views that real people hold.

To Jamie Dreier,

I’m not so sure that the number of citations of philosophy papers by papers that are not philosophy papers (and conversely) is negligible. About 25% of the citations to my most-cited paper (it’s in meta-ethics) are not from philosophy papers but from a range of papers in other disciplines mostly law. As for my second most-cited paper (it was published in the The Philosophy of the Social Sciences), less than a third of the citations are from philosophers, most of the citations being in books or papers written by historians, political scientists, classicists, communications theorists, psychologists and sociologists. Furthermore in that paper less than half of my references were *to* other philosophers and only one to a philosophy paper that had been published in the previous ten years. Now it may be that I am outlier here, but it is at least a *dubious* assumption that philosophers only read (and are read by) other philosophers. But let us suppose that this is the case. Does it follow that ‘the [average] number of citations per article have to be the same as the number of papers an average article cites’? Not if we are talking about the average article published in (say) 2005. Consider an article published in that year which manages to get five citations during the next ten year period, which, we will assume, is the average. Does this mean that the papers published in the period will have on average only five references? No it does not. For the papers citing it may *also* be citing works published decades or even *centuries* beforehand. In philosophy, as opposed to many other subjects, we are competing for readership, attention and citations not only with our contemporaries but also with the mighty dead. My work could be replete with references to Russell, Moore and Sidgwick but this is not going to help precarious young philosophers who desperately need to pile up citations in the here and now in order to argue their way into a decent job.

I will add something else. Unless you are a metropolitan philosopher, personally well-known and well-liked in some of the big cultural centers, it can take *decades* for your work to be noticed. I published eight journal articles in the first ten years of my post-PhD career (1985-1995). NOW (I am happy to say) they are pretty well-cited with an average citation-rate that I am quite pleased with. But, Lord, it has taken me a long time! 87% of the citations to those articles date from 2000 (five years after the last was published) and 70% from 2006, (eleven years after the last was published). Indeed I have one paper which got its one and only citation *a quarter of a century* after it was first published. Now in one way this is a rather backhanded message of hope for young philosophers (‘Don’t despair – nobody may be paying attention now but in 25 years things may be looking a little different!’) But in another way it reinforces the problem. We are all in a tacit competition for the attention of our peers. This is because attention is a limited resource and much more is published in most philosophical areas than anybody can actually manage to process. (This is certainly true in meta-ethics which is one of my specialities.) So if somebody somewhere is reading and citing you, there is somebody somewhere else who is not getting read or cited. And if the young Charles Pigden is lucky enough to be getting the belated recognition that he used to think he deserved, this means that young philosophers nowadays are competing for attention not only with the old Charles Pigden (who continues to publish) but also with my younger self. And they are also competing with the younger versions of every other older philosopher whose early work is still read and cited, whether or not that work was cited when it first came out.

We also have a solution to Jamie’s puzzle. If, over a ten year period, the average paper gets only five citations how can it be that the average paper cites more than five items? Answer: many of the items that they cite fall outside the ten-year period. And we have a tentative explanation of the alleged fact that recent philosophy papers are less cited than recent papers in some other disciplines. It may be that philosophers cite less than (say) psychologists, but it may also be the case that *when* they cite they are less likely to cite recent papers.

Hi Charles,

Didn’t Tom Hurka already make the point about citations within a given period of time? I do hope that in future work you will be sure to credit him.

It looks like just about all citations of my papers are in philosophy papers (I just looked on Google Scholar). So, I guess one of us is an outlier.

Mea culpa. I do indeed owe Tom and apology for plagiarising one of his points. And you may of course be right that I am the outlier when it comes to non-philosophical citations. But I wonder Jamie what about the papers *you cite* as opposed to the papers that *cite you*? Are *all* the papers you refer to philosophy papers? It has just occurred to me that another factor forcing down the citation rate for recent philosophy papers might the fact many of us have a propensity for exogamous citations. Think, for instance, of all those papers in moral psychology with extensive citations to the psychological literature and the papers in ethics which draw on economics, sociology or evolutionary theory. If many of us are indeed prone to exogamous citation, then, as with our penchant for citing the old or the dead, this probably means that we have less attention pay to the latest issue of Philosophical Studies. But if this *is* part of the explanation for the low citation rates for recent papers, it is not clear that it is something that we ought to change. Philosophers who confine themselves to the purely philosophical literature are on the whole less likely to do good work than those that take a larger view. If philosophy really is continuous with science (including the social sciences) then surely we OUGHT to be citing outside the discipline. But of many of us are given to playing away, that means we will have less time and energy to read and cite those papers that have been recently produced on our home turf.

(Scolding you for not giving Tom credit was supposed to be a joke.)

I do occasionally cite something other than a philosophy paper — anthropology, linguistics, economics, a poem here and there. And I agree that this isn’t on its face a problem. I can’t tell whether the evidence we’ve seen is evidence of a problem at all.

It’s not all that clear what counts as citation by a work of philosophy, by the way. I took a look at Hurka’s Google Scholar pages, and he has some (a lot of) citations by papers published in economics journals, by e.g. Charles Blackorby, who works in an economics department but whose papers are by my standards works of philosophy.

My mea culpa wasn’t entirely serious either. I agree that people who work in other areas and publish in non-philosophy journals may well be doing what can reasonably be described as philosophy. But I suspect that for statistical purposes their papers would not count as philosophy papers. Thus references to such papers would count as non-philosophy references, and citations in such papers would count as non-philosophy citations. If much of what we read and cite is written by non-philosophers or by philosophers who are old or dead, that means that the papers of young philosophers are less likely to be read or cited (since attention is for each us a limited resource) . What Mizrahi was complaining about (if I understood him correctly) was that young philosophers were not getting the citations they need and deserve mainly because of the bad and unscholarly behaviour of their seniors. But if some of these absent citations are due to a habit of reading and citing non-philosophers and if some are due to a tendency to read and cite the mighty dead, it is not clear that the behaviour is either bad or unscholarly. And if isn’t bad or unscholarly then it is not clear that it ought to be changed.

Charles, I’m worried about the “ifs” in your argument. I’m finding too many of them, and those particular ifs are too iffy. Take your first premise:

(1) “If much of what we read and cite is written by non-philosophers …”

Wouldn’t “some” be better than “much” here? Without this revision, I don’t see how this assumption could be plausible. *Maybe* a case for “much” could be made for those specializations that are supervenient on other fields, e.g. philosophy of science, philosophy of literature, philosophy of language, philosophy of mathematics, etc. But it’s unlikely to hold for traditional core areas of philosophy such as metaphysics, normative ethics, or history of philosophy. I have similar worries about your second premise:

(2) “If much of what we read and cite is written by … philosophers who are old or dead …”

Under what conditions could this be true, given that a keyword search will turn up results that are not limited by age or publication date? The only conditions I can think of is that one has not done the basic research legwork I described earlier, but that’s just bad scholarship. So your third premise,

(3) “if some of these absent citations are due to a habit of reading and citing non-philosophers”

describes a habit that is unlikely to hold across the field of philosophy as a whole, whereas your fourth premise,

(4) “ if some [of these absent citations] are due to a tendency to read and cite the mighty dead”

does not do any explanatory work, since a tendency to read and cite the mighty dead is compatible with a tendency to read and cite the mightless living. So your conclusion, that

(5) “it is not clear that the behaviour is either bad or unscholarly”

does not follow. The behavior would seem to be unscholarly at the very least.

As to what Mizrahi is complaining about, his three recent updates at http://philosopherscocoon.typepad.com/blog/2015/11/too-tight-to-cite-.html make clear that he is not concerned merely with the fact that “young philosophers [are] not getting the citations they need and deserve mainly because of the bad and unscholarly behaviour of their seniors.” He is expressing a concern about the citation practices of the field as a whole:

“When looking at these data, instead of thinking that Philosophy isn’t as bad as Religious Studies, I’d rather think about ways to make Philosophy as good as HPS.”

– and, in my opinion, he is getting unfairly pounded to pulp for voicing this very legitimate concern.

First, as a grad student five to eight years ago writing seminar papers about topics I was not already familiar with I was doing literature searches with fresh eyes that repeatedly uncovered papers that were relevant but never cited, or philosophers with similar views who were seldom discussed together because they traveled in different sub-circles. I had the strong sense that had I ever wanted to turn one of these papers into an article then the fact that I discussed papers that were never previously cited or brought together views not usually juxtaposed would have actually diminished the chance that such a paper would be accepted to a good journal.

Second, my actual specialization is interdisciplinary to the point that I could spend page after page pointing out that scholars in different fields (even ones considered interdisciplinary) discuss the same topics and often make similar arguments without any seeming awareness of one another. But this is of almost no interest to the editors and reviewers who I have to please when I writing an article for a disciplinary journal that would offer the greatest return in terms of career advancement. The ‘points’ awarded for publishing in an interdisciplinary journal where this kind of thing would welcomed are rather limited.

Dear Adrian (if I may),

You are right of course that some of my ‘if’ are big ifs which means that my conclusions are consequently rather iffy. And you are right too that papers in certain areas, such as the philosophical logic or analytical metaphysics are not likely to cite or be cited by non-philosophers. Nonetheless, what I want to suggest is that evidence for some of my claims is to be found in you own work. One of my contentions is that *one* reason for the low citation rates of recent articles by youngish philosophers may be that their work is in competition for attention and citations with older works by older and better-established philosophers as well as with the famous productions of the mighty dead. Let us take your book *Rationality and the Structure of the Self: the Humeans Conception* which was first published in 2008. It has a truly impressive bibliography with about 462 items (calculated by counting the pages with an estimated 14 items per page). It’s a ‘core areas’ sort of book since it is concerned with metaethics, the history of philosophy (Hume & Kant), metaphysics (the nature of the self) and moral psychology (ditto). There is also a lot of stuff about decision theory and rational choice. It is clear a] that you are an amazingly well-read and wide-ranging philosopher (a fact that is all the more amazing as you have a parallel career as a conceptual artist) and b] that you are extremely thorough, meticulous and scholarly when it comes to your citations. For that very reason it is worth asking how many recent papers by (at that time) younger philosophers you manage to cite. By my count (using a word search on the pdf) you cite 25 items published between the years 2000 and 2008 inclusive. That’s about 4.5% of the total. There are three self-citations from that period, two citations to newspaper articles and two citations to new editions of classic works (Kant’s ‘Groundwork’ and Keynes’ ‘The Economic Consequences of the Peace’, one of which is not strictly philosophy). You cite recent works by a number of philosophers who were already famous or well established by 2000 – van Benthem, Schiffer, Brandom, O’Niel, Mark Kaplan, Fodor, Bolker, Hanna, Hoyningen-Huene and Rawls. In most cases the cited items represent recent installments of research programs that had been going on for decades. The Rawls citation is technically recent but, I suspect, not really so, since you were probably conscientiously citing, in a published source, material that you had heard from the lips of Rawls himself at a much earlier date. (It is very useful to those of those were fortunate enough to be Rawls’s students to have his lectures in print!) Gigerenzer (two items) is a psychologist not a philosopher (so that the items in question are exogamous citations) but with Gigerenzer, too, the citations would appear to be representative samples from a long-term research program that by 2008 had been going on for decades. (Gigerenzer turned 61 in that year.) Thus the only citations to recent publications by philosophers who were at that time young are the citations to de Jongh & Liu and to Elijah Millgram. That’s less than 0.5% of your total citations.

Significantly, there are no citations at all to ‘Hume Studies’ and hence none to the young Humeans who publish in it and who might have had something relevant to say. Instead you appear to pursue your anti-Humean agenda in part by pitching on the best Humean you could find (specifically Annette Bair) and conducting an extended argument with *her*.

Let me stress that this is not intended as a *criticism*. RSS:HC clearly represents half of your summa. It is the fruit, I suspect, of twenty-to-thirty years’ critical engagement with the literature. You refer to the books and articles that had influenced your thinking (as either importantly right or interestingly wrong) over two or three decades. It would have been simply silly to have neglected those texts in favour of recently published stuff. Nor are you fixated solely the papers that were influential when you were younger. On the contrary the bibliography suggests a conscientious effort to stay up-to-date. But the recent texts that you cite were almost all by philosophers who were already famous or well-established. Thus the texts that you read and subsequently cited tended to be by authors you had reason to believe would be worth reading, not by newcomers whose work might very well be otherwise. That is perfectly sensible since more is produced in the areas that interest you than any single person, no matter how hard-working, gifted and conscientious, can possibly hope to process. We *have* to be selective in what we read and cite, and focusing on authors we know to be worth reading is probably the best way to go. Thus in concentrating on Simon Blackburn or Onora O’Niel you were doing the sensible thing. But the consequence is that there is probably relevant work somewhere by a young Simon or a young Onora which you have neither read nor cited.

Contemporary philosophers (people publishing right now) compete for attention and citations with one another. In this market (given the pressure to publish ) there are about as many producers as consumers. But we are not just competing for attention and citations with one another – we are also competing for attention and citations with the past productions of older philosophers (if we are young) and with the past productions of our contemporaries (if we are old). And both groups (the young and the old) are competing for fame and attention with the productions of the mighty dead. Not only that. Since many of us think that a philosopher who is just a philosopher is not much of a philosopher, we are also competing for attention and citations with the work of a wide range of scholars in related disciplines. (It is good to read Gigerenzer but when you are reading Gigerenzer there is a philosopher somewhere else who you are NOT reading.) Is it any wonder, given all this, that the average citation rate for recent philosophy papers is so dismally low? And is it any wonder that it is more established philosophers that tend to get the lion’s share of those citations?

Yikes, Charles.

There is a lot in your reply for me to think about, and I’m not sure I can absorb all of it on a first pass. But I’ll try. However, I have to first thank you for the only (to my knowledge) published discussion of RSS:HC, which is often downloaded, frequently used, but never mentioned in print. So many thanks for that.

Since many of your points pertain specifically to that work, let me first address the points related to this DN topic more generally, and try not to contradict myself when I then attempt to apply my answers to your specific observations about RSS:HC.

(1) “One of my contentions is that *one* reason for the low citation rates of recent articles by youngish philosophers may be that their work is in competition for attention and citations with older works by older and better-established philosophers as well as with the famous productions of the mighty dead.”

It’s difficult for me to evaluate this claim, because I’ve been out of the professional side of the field too long to know the ages of most of the people whose work I read and cite (I do know, however, that de Jongh is a mighty old person whereas Liu is a recent Ph.D., and that Millgram is closer to my age than to Liu’s). I think your assumption is a reasonable one; but also that my inadvertent “veil of ignorance” on the ages of most of those authors suggests an answer to it: That it’s precisely that competition with older and better-established authors that challenges younger authors to do their best work. If the quality of the work deserves mention, then other things equal, perhaps they will get it. One example would be Rawls’ early article, “Outline of a Decision Procedure for Ethics” (1957), which had an electrifying effect on the field and virtually ensured attention to what he had to say thereafter. In the General Introduction to RSS I talk about the dilemma younger authors face in having to confront their Oedipal relations to their forebears: that they risk retaliation for opposing or outdoing them, but can’t produce meaningful work unless they take that risk.

(2) “[M]ore is produced in the areas that interest you than any single person, no matter how hard-working, gifted and conscientious, can possibly hope to process. We *have* to be selective in what we read and cite, and focusing on authors we know to be worth reading is probably the best way to go.”

I agree with most of this, but it’s that last clause I would question: Why is selecting according to “authors we know to be worth reading” preferable to selecting according to content relevance? Although you are quite right that we can’t process everything that is produced, we can at least sift through abstracts, browse through books and journals, track down relevant citations in those publications, and just keep doing that until we feel we at least get the big picture on the issues. Had I not done that in RSS:HC, I never would have discovered Ward Edwards, an early decision theorist who is very interesting and was very influential at the time (early 1950s) but is now almost never discussed. Plus it’s more interesting than confining oneself exclusively to authors one already knows. But for me the most important reason to prefer the keyword search to the author search is in order to be sure one is not simply repeating (and indeed without citation) what someone else has already said.

(3) “[3.a] Contemporary philosophers (people publishing right now) compete for attention and citations with one another. [3.b] In this market (given the pressure to publish ) there are about as many producers as consumers. [3.c] But we are not just competing for attention and citations with one another – we are also competing for attention and citations with the past productions of older philosophers (if we are young) and with the past productions of our contemporaries (if we are old). [3.d] And both groups (the young and the old) are competing for fame and attention with the productions of the mighty dead.”

[3.a] I think is right.

I also agree with [3.b], but I think we all *must* resist the pressure to publish no matter what, no matter what. My choice was to get kicked out of the field, rather than publish enough to have secured my place in it but too much to have secured its quality according to my own standards. I’m not suggesting that strategy for anyone else. But I do know from talking to younger philosophers that the pressure to publish by now has become so extreme that it’s virtually impossible to give any one article or book manuscript the time and attention one feels it needs and deserves. That is, picture this: We are being required by these pressures to defile our own, deeply instilled standards of philosophical scholarship in order to get, keep or advance in our jobs as philosophers! This has got to stop. It is making the field look bad and it is destroying our scholarly credibility.

[3.c] and [3.d] I think are right, but that this is a good thing (see (1) above).

(4) And now, briefly, to RSS:HC. You say, “[I]t is worth asking how many recent papers by (at that time) younger philosophers you manage to cite.” See (1) and (2) above, and also [3.b]. I have to accept your summary of its citation patterns – and much appreciate *its* thoroughness and meticulousness. And it is true that there are no citations to Hume Studies. That is because RSS generally is not primarily directed to exegesis of the historical figures. RSS:HC turns to Hume himself only as a last resort, after finding no satisfactory contemporary solutions to the problems such a view raises.

So I do accept your conclusion that “the texts that [I] read and subsequently cited tended to be by authors [I] had reason to believe would be worth reading.” Yet I would deny any attempt to restrict those authors to the mighty elderly or already known. I have reason to believe any authors to be worth reading whose texts or abstracts convince me that they are.

All best,

Adrian (you may) 🙂

Hi again Charles,

This is a second (and perhaps final) installment of my reply to your post. Again I have to begin with thanks for your very generous comments about the bibliography and citation practices of RSS:HC. The bibliography is less impressive than it appears, because first, due to the large degree of cross-polination between that volume and the second in the project, *Rationality and the Structure of the Self, Volume II: A Kantian Conception*, the bibliography is the same for both RSS:HC and RSS:KC. So it contains works cited in both. For an accurate list of the works I cite only in RSS:HC, you have to look at the footnotes to that volume. Second, the bibliography also contains works that influenced my thinking in either or both volumes, but that were not explicitly discussed in either text (Robert Howell’s very important book on Kant’s Transcendental Deduction would be an example). But third, and perhaps most importantly, these were simply the citation practices I learned in high school and that were reinforced by those in the books and articles I read in college and graduate school. If more recent graduates are learning different practices (and not just different formats), that is worthy of note.

This last point may provide part of an answer to your concluding questions, “Is it any wonder, given all this, that the average citation rate for recent philosophy papers is so dismally low? And is it any wonder that it is more established philosophers that tend to get the lion’s share of those citations?”

These are very large questions and I can’t purport to offer complete answers to them. But I do know that recently mounting publication pressures are making it much harder to produce *only or even primarily* work whose content compels one’s attention, because even the most fleeting conference or workshop or paper comments must be mined for their potential to (to use the lingo) “get a publication out of it.” To the extent that recent writing practices are being driven by the need to “get a publication out of it” *rather than* to take the risk of deliberately competing with the mighty dead, the relatively low average citation rate for recent philosophy papers will contain a higher proportion of contributions that are publishable but marginal in significance, and their citation rate will depend on other factors, such as the professional status of the author. More recent and more marginal contributions by younger authors desperate to publish will suffer accordingly.