A Bias Against Simplicity?

Kieran Healy (Duke) recently presented a paper entitled “Fuck Nuance” at the American Sociological Association’s annual meeting. He writes:

Nuance is not a virtue of good sociological theory. Sociologists typically use it as a term of praise, and almost without exception when nuance is mentioned it is because someone is asking for more of it. I shall argue that, for the problems facing Sociology at present, demanding more nuance typically obstructs the development of theory that is intellectually interesting, empirically generative, or practically successful.

He discusses the problem in an interview at The Chronicle of Higher Education:

In social theory, nuance is bad when it becomes a kind of free-floating demand to make things “richer” or “more sophisticated” by adding complexity, detail, or levels of analysis, in the absence of any real way of disciplining how you add them. People just keep insisting on a more-sophisticated approach and act as though simply listing the many ways something might be more complex is the same as having a better theory of that thing. In such cases, levels and aspects and dimensions may just pile up in a heap. It is especially bad when you habitually make this your first move when deciding whether an idea or theory is any good.

Meanwhile, in a forthcoming paper in Argumentation entitled “Why Simpler Arguments Are Better,” Moti Mizrahi (Florida Institute of Technology) writes:

It appears that many philosophers are often bedazzled by complex arguments. They admire the depth and complexity of a philosopher’s arguments even though, when pressed, they might admit that the philosopher’s arguments are often not of the highest argumentative standard. This is the impression one gets when it is said with approval of philosophy in general that it is “difficult”…,“hard”…, or “complicated”…, and of particular philosophers, like Nietzsche and Hegel…. I think that this is a mistake. That is to say, I think that, instead of admiring complexity in philosophical argumentation, we should prefer simplicity.

He then goes on to provide some rather reasonable arguments in favor of simplicity, ceteris paribus, in argumentation.

These two papers had me wondering about the extent to which philosophers are enamored with complexity (or nuance — though I don’t mean to equate the two), whether it’s a problem, and further, whether there is a bias against simplicity.

In figuring this out, it isn’t sufficient to observe that philosophers have spent a lot of time working on complex arguments of their own, or on the notoriously complex work of some historical figures. We’d expect more complex arguments to take more time to unpack and understand.

It would be helpful if we had two roughly equally compelling arguments of varying complexity for roughly the same thesis, along with an observation that philosophers prefer the more complex one. Is there an example of this?

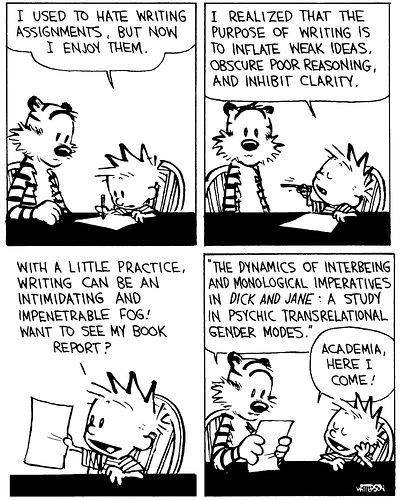

(Nor is complexity the same as obscurity, but if there’s a slender reed of an excuse to put up a Calvin & Hobbes, I’ll probably take it.)

Clearly you need to provide a more sophisticated distinction between ‘nuance’ and ‘complexity’, preferably using long words from more than one language.

The Calvin and Hobbes cartoon identifies another virtue of simplicity not specifically mentioned in the OP. It is easier to see the flaws in a simple argument. If I add enough detail, I can obscure my weak foundations.

Grasping “complexity” in biology and Earth Systems science is crucially important at this time in our history, as is being able to visualize complex wholes and articulate ways in which they operate and interact, and the simpler and more clearly that articulation is carried out, the better. I think the sort of “nuance” Healy is criticizing is a kind of dancing, dodging, denying obscurantism that serves the opposite purpose.

Like Hey Nonny Mouse, I think there’s a real cost to complex arguments in that they are correspondingly much harder to assess. On a hunch that referees most often reject papers because they can see clear objections, I wonder if this results in better publication rates for more complex papers, and in turn incentivizes against clarity.

I think that Moti Mizrahi misinterprets many of the claims he cites at the outset of his paper. Simplicity–using fewer premises to arrive at a conclusion when possible–is surely a virtue of philosophical writing. But the “greats” are not being described by Danto, Wood or Kelly as using too many premises. Rather, the quoted claims being made about Nietzsche and Hegel are: that they are “hard to understand”, that they “embrace strange conclusions” and that they are “difficult”. A more charitable reading of these descriptions would be: Hegel and Nietzsche have premises (and conclusions) which are unfamiliar to us, and thus harder to understand. Another (more critical) complaint might simply be: it is hard to see how their conclusions are related to their premises. Another might be: they use terms which we don’t initially understand. Note that none of these has anything to do with complexity.

Next: it is important to remember that one reader’s complexity is another’s simplicity. The purpose of writing is to convey ideas to readers, and what one reader finds “superfluous” another may find helpful. Take Mizrahi’s own use of a sciencey-looking graph to illustrate “Curve-fitting and goodness-of-fit”. Logically, the graph is expendable, since the point could be made without it. Yet, it aids in understanding, at least, for me. Is it “unnecessary complexity”? There is no single answer to that question, and anyone who thinks that there is a single answer has forgotten the distinction between constructing an argument and writing the argument down for a general audience.

While I tend to agree with the conclusion of the notion that scholarship ought not to be needlessly complicated, hard, or difficult to understand, I’m not sure I buy Mizrahi’s premise that philosophers tend to prefer complicated, hard, or difficult arguments.

Indeed, I’ve always been taught to try to write in a way that will result that would allow my arguments to be understood by a reasonably bright lay person. Moreover, though it might be more indicative of my friends and colleagues than trends in the field as a whole, I’ve often heard people being critical of figures such as Hegel and Nietzsche because their work is needlessly difficult to make heads-or-tails of.

“When someone prides himself on being able to understand and interpret the books of Chrysippus, say to yourself, ‘If Chrysippus had not written obscurely this person would have had nothing on which to pride himself.'”

–Epictetus, Handbook 49

“But no, instead someone [enters my school and] says, ‘I want to know what Chrysippus means in his work on [the logical puzzle called] “The Liar.”’ If that is your design, go hang yourself, you wretch!” –Epictetus, Discourses 2.17.34

Paul Feyerabend once said, “[Philosophy of science] has by now become so crowded with empty sophistication that it is extremely difficult to perceive the simple errors at the basis. It is like fighting the hydra – cut off one ugly head, and eight formalizations take its place. In this situation the only answer is superficiality: when sophistication loses content then the only way of keeping in touch with reality is to be crude and superficial. This is what I intend to be.” (“How to Defend Society Against Science,” 1975)

This is a coincidence. I’m just sketching out a list of problems in philosophy and a dislike of simplicity is near the top.

“It would be helpful if we had two roughly equally compelling arguments of varying complexity for roughly the same thesis, along with an observation that philosophers prefer the more complex one. Is there an example of this?”

I’m not sure about this. Conclusions may be simply stated but arguments have to be as long as they need to be in order to convince someone. I feel that the problem is slightly different, in that philosophers will often prefer more complex arguments if they support theories that the person wants to endorse. Iow, it is not a difference in the choice of argument but in the choice of theory, where some theories require a lot of obfuscating argument in order to seem plausible.

It seems a vital issue since complexity is emergent and philosophy requires us to backwards engineer it. This cannot lead anywhere but to greater simplicity.

If brevity equalled simplicity (and if my hobby-horse in not too tired) then I’d cite Nagarjuna’s ‘Verses on the Middle Way’ as a simple solution for philosophy that is regularly overlooked in favour of more complex approaches, but unfortunately they are not the same thing.

Like some of the other commenters, I also doubt Mizrahi’s claim that philosophers, at least analytic philosophers, are enamored of complexity for its own sake. He discusses Hegel and Nietzsche, but they are not often taught by analytic philosophers. He also quotes Kelly as saying that “great philosophers who embraced strange conclusions are praised in eulogies for their willingness to follow the argument where it leads,” but this seems to me not a comment about the complexity of the argument but about the strangeness of the conclusion. This seems like the sort of praise that might be given to a philosopher who follows the argument for the Repugnant Conclusion to its logical end, but that argument isn’t particularly complex in its essential form.

As for the Healy piece, the excessive nuance he discusses doesn’t seem to me to be a pervasive problem in analytic philosophy; we’re generally happy to abstract away from stuff in pursuit of our theorizing. Healy describes the nuance-promoting theorist as saying “How does your theory deal with Structure, or Culture, or Temporality, or Power, or [some other abstract noun]?”–these all seem like things that analytic philosophers happily ignore when they’re not what we want to talk about. (And in this respect I think analytic philosophy could stand to be more nuanced.)

There’s the issue that philosophers are expected to deal with a lot of quibbles (or detailed objections if you’re more sympathetic to them). I’m not sure if that’s the same as the nuance problem Healy is talking about, though. It’s not “Add this concept to your theory!” as much as “Fit your theory to this counterexample!”

It’s not precisely the same phenomenon but Healy’s discussion of connoisseurship reminded me of a familiar move in discussions after ethics talks, where someone often takes a speaker to task for failing to recognise the complexity of ethical life, the need to appreciate the subtleties of lived experience and so on. I’m sure that such comments are well-intentioned, but they often come across more as an exercise in establishing the questioner’s refined moral sensibility than as a real attempt to move discussion forward

On the other hand, whenever they have the luck to discover something certain and evident, they always present it wrapped up in various obscurities either because they fear that the simplicity of their argument may depreciate the importance of their finding, or because they begrudge us the plain truth. (Descartes, *Rules for the Direction of the Native Intelligence*, Rule 3)

Healy’s piece says in 12 pages what can be, and is, said in three sentences (and with less cheek):

“By calling for a theory to be more comprehensive, or for an explanation to include additional dimensions, or a concept to become more flexible and multifaceted, we paradoxically end up with less clarity. We lose information by adding detail. A further odd consequence is that the apparent scope of theories increases even as the range of their actually-accomplished application in explanations narrows.” (page 6 of his paper).

The paper is therefore either a piece of performance art, or a performative contradiction.

The suggestion that philosophers (or any thinkers, for that matter) should prefer argumentative simplicity sounds right to me. I try to be simple in my work (but then, of course, worry I’m being simplistic).

I can’t think of any examples where a simple argument is put aside for a complex one by philosophers, despite both being available. However, I can think of one reason for philosophers to like complex arguments, and even prefer them over simple ones.

Philosophers (both at the student and professional level) would complexity because

(a) there are good and important philosophical arguments which are complex, arguments we must as students learn about and

(b) we like to practice, even as we continue into the profession.

Complex arguments allow us to practice (no matter how flawed or insipid they might be) whereas simple arguments don’t (no matter how powerful they might be).

This might lead us to tolerating or holding on to a complex argument for something when there might be a simpler argument just waiting to be discovered. (I wonder if there’s a career for philosophers who look at complex arguments and find simple alternatives?)

I think there’s an important distinction to be made between the complexity _of arguments_ and the complexity _of natural processes_. Of course, many analytic philosophers will think only of the first–what else is there? Philosophers who take biology seriously, on the other hand–environmental philosophers, for example–will recognize the importance of the latter, and admit that biological complexity has gone unacknowledged for all too long, given our culture’s traditional conceptual imposition of simple, machinelike properties upon living systems, something that makes them _seem_, erroneously, open to infinite manipulation, which we are now discovering has been to our own peril. Perhaps what we need are simple _arguments_ waking us up to the complexity of _nature_ at this time in our evolution?