Humility in Philosophy

Because the views we espouse are always open to objections and disagreement, our practice at its best nurtures in the philosopher a capacity to withstand huge shifts in her understanding of even her most deeply entrenched beliefs about how things are in the world. Good philosophy of all stripes fosters in the practitioner the virtue of epistemic humility.

The best philosophy teachers are the ones who are able to model this virtue. They show their students, à la Socrates in at least the early Platonic dialogues, how the right kind of conversation can bring to consciousness the utter preposterousness of something that one has always taken for granted and then how to survive finding oneself turned around in one’s shoes. Epistemic humility sometimes takes the form of humbleness, but not always. It can be intensely empowering for people who have always assumed that the systematically poor way the world treats them is fundamentally the way they deserve to be treated.

The worst enemy of the best philosophy is ideology in all its forms. Philosophy at its best evinces deep skepticism about the stories powerful people and institutions tell about How Things Are.

I guess it’s Nancy Bauer week at Daily Nous. The above is from an answer Professor Bauer (Tufts) gives to the question “How can philosophy make itself more relevant?” at Aeon’s Ideas site.

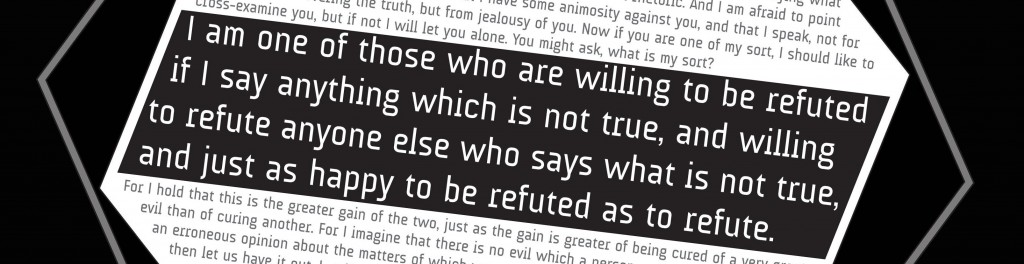

When I introduce students to philosophy one thing I tell them I’d like to see them cultivate in themselves is “the philosophical disposition,” exemplified in some respects by Socrates:

Bauer concludes her answer by saying that “The natural home of philosophy is in the agora, not the ivory tower. The question is whether the academy can bear to confront that truth.” What would it mean for the academy to “confront that truth”?

In order to philosophy to be active “in the agora”, professional philosophy is going to have to value work directed to, or involving, the public. At present, that work tends to be viewed as peripheral and best and unimportant at worst. Some philosophers even seem to see it as a harmful “dumbing down.” Personally, it seems essential to our duty to do public good.

“natural” home?

One thing that “The natural home of philosophy is in the agora, not the ivory tower” might mean is that academic institutions aren’t the only places where (professional, high-quality) philosophy is done. In other words, not all philosophy is *academic* philosophy.

“Good philosophy of all stripes fosters in the practitioner the virtue of epistemic humility.”

I don’t know about this. In my experience, philosophers have more professional success when they refuse to see things from another point of view, and hold fast to their own view. (Success = respect by other philosophers, won esp. by writing and conversing.) This seems to me an attitude that’s often cultivated by reading good philosophy as well.

Professional academic philosophers are scholars first.

“In order to philosophy to be active ‘in the agora’, professional philosophy is going to have to value work directed to…the public…it seems essential to our duty to do public good.”

Do professional philosophers have a duty to do public philosophy? If so, is this a moral duty? Or, is it good to do public philosophy but not (morally) required?

Confronting the truth, if it is one, that “the natural home of philosophy is in the agora, not the ivory tower,” might involve accepting that doing public philosophy is a (moral) duty. It might also involve those within the academy facilitating fulfillment of that obligation by allowing space for and incentivizing the practice of public philosophy. For instance, perhaps doing public philosophy should “count” to some degree toward securing tenure.

@Anon Grad. I’m not seeing the incompatibility between being a scholar and being of public value. I would like to see scholars listed to. The public funding we receive is justified by the fact that we provide things of value in return.

If Socrates really was “just as happy to be refuted as to refute”, he hid it well.

I certainly agree with Hey Nonny Mouse, Dan Hicks, and CMC. I’d like to continue down their lines of thought, though. This is because I do see engaging in public philosophy as a duty of academic philosophers. When I first assert this to other philosophers, though, they usually react like I’m some sort of double agent. They assume that making such a claim must be a result of thinking that most of what passes for philosophy today is junk and that we should all start writing pop-philosophy to fill the racks at Barnes and Noble. I think pop-philosophy and public philosophy aren’t the same thing, though.

Pop-philosophy is just one way to do public philosophy– which I think is really about doing philosophy with the goal of the betterment of ordinary life in the human community. Another way to do this is to (i) keep working on the same things we always work on, just trying to include ways it could be important to ordinary, non-academic life. It could also involve (ii) asking if there’s anything important about the way we live our ordinary lives that would imply that we’ve already got an answer to the question. Some might hold that to bring these questions to all philosophizing would, in effect, rule out much of today’s philosophy– certainly many popular issues in Analytic circles anyway. I think holding such a view involves underestimating and misunderstanding analytic rigor, though. I think Moorean reliance on common sense is ultimately about trying to keep (ii) in mind– about adopting the maxim that I will only believe in the seminar room that which I could implement in my life outside of the seminar room. Even logic-choppers like the logical empiricists have been worried about (i) as well. In their Manifesto, they stated:

“the Vienna Circle believes that in collaborating with the Ernst Mach Society it fulfills a demand of the day: we have to fashion intellectual tools for everyday life, for the daily life of the scholar, but also for the daily life of all those who in some way join us in working at the conscious re-shaping of life”.

As for other ways to confront the truth of Bauer’s claim, I think many of these can be done in our teaching. Simply don’t act like an ivory tower representative. Don’t be pretentious. Be willing to say “I don’t know”. Be willing to say “you’re right”. Be willing to tell your students when they bring up something you haven’t thought about before. And when they bring up things you’ve heard a million times before, point out that they’ve stumbled upon a classic problem rather than telling them their worry has been answered many times before. Most importantly, connect the philosophical enterprise to things that they recognize. Follow Justin’s lead and show them comedy clips. Just as easy and just as effective is playing them music. I work mostly in logic and the philosophy of language and I’ve found most of the issues I’m trying to tackle in the music I listen to.

Practically speaking, it’s completely understandable for any human being, particularly for academics, NOT to be as happy being refuted as refuting others. We want to be of social worth, of value to others, and if you keep getting things wrong, you’re not going to feel that you’re are as valuable as others who are not being refuted as often as you. This goes for us doubly as academics. Our very livelihoods and professional reputation depends on our getting things right at some of the time, and on not being constantly refuted.

Being refuted once in a while should never harm one’s reputation or social (or professional) worth. However, unless we wish to stop praising getting things right over getting things wrong—which essentially is to stop valuing the True over the not-True—we’re very unlikely to cultivate a social environment in which people feel genuinely as happy being refuted as they are refuting others.

Though he does talk about being willing to, like David Wallace, I am not convinced that Socrates (at least the Socrates in the early dialogues) offers us an example of a person willing to change his mind. So, while we might want to teach the humility he preaches, I am not sure we want to teach him as an exemplar of living up to that humility.

On the other hand, Socrates does offer us a powerful model for something else we should be teaching, commitment. When it comes to teaching controversial issues, it is easy (maybe easiest) to avoid showing our hand and leaving the students no clue what we think. I had a great teacher like that in college, where we had absolutely no idea where he stood on anything and it thus forced us to decide on our own. This was useful, and it helped us with lots of important intellectual skills. But, by itself, it deemphasized, and thus didn’t allow us to learn through an example, what appropriate commitment is like (and how it differs from dogmatism). I have come to think that the “don’t show your hand” style might make the most sense with introductory level classes, where students only have the experience of one professor and might take any view as typical or necessary for philosophy writ large. But by the time students have had several classes, and have seen that philosophers disagree with each other, I see it important to then change the strategy to show how, without being dogmatic (or even settled), we can be committed to certain beliefs and act for change (where the beliefs call for such).

@ Aaron W

“However, unless we wish to stop praising getting things right over getting things wrong—which essentially is to stop valuing the True over the not-True—we’re very unlikely to cultivate a social environment in which people feel genuinely as happy being refuted as they are refuting others.”

When you are refuted this means you gain insight into the deficiencies of your argument. This brings you closer to getting things right, although at the cost of having to admit you failed to get things right earlier. If you value getting things right, you should actively seek out objections (which, if fatal, may be refutations) to your claims. Praise for getting things right should not be confused with praise for appearing to get things right; philosophy (and science) praises the former, while sophistry praises the latter.

Socrates would have loved social media!

I would guess that Socrates was happy to be refuted but we’ll never know. Is it really true that academic philosophers practice epistemic humility? It does not seem that way to me. Bradley calls metaphysics ‘an antidote for dogmatic superstition’. As such it is widely ignored and remains moribund in academic circles. Too dangerous by half.

My previous comment was not clear. I meant to suggest that if philosophers had more epistemic humility they would not be so averse to metaphysics.