Philosophy’s Exclusion of Literary Writings

Chiara Bottici (New School) was one of the opening speakers at the Night of Philosophy held at the French Embassy in New York City on April 24th, 2015. She chose a controversial figure to focus on—Machiavelli, whose “very status as a philosopher is contested”—in order to get at the question of what does and what does not count as philosophy.

Towards the end of her talk, she asks:

Why are philosophers reluctant to take literary writings seriously? Why do philosophers, beginning with Plato, feel the need to ban the poets, whereas literary theorists do not feel that need? Is it to reinforce the idea that philosophy concerns arguments, reason, the logos, whereas fiction concerns stories, metaphors, and myths, and is thus somehow more primitive? But has philosophy ever liberated itself from myth? And even more so: does it even need to do so in the first place? Why cannot stories, and even mythical ones, be able to carry the logos itself, if it is true that at the time of the Homeric poems mythos and logos were used as synonyms and, correspondingly, the first philosophers kept intermingling them? Why has the logos subsequently taken on such an exclusionary drive?

I’m torn. I think good philosophy generally aspires to a kind of rigor and transparency that is hard to imagine being present in good literature. But ways of communicating have their limits, including philosophical discourse. If you haven’t had the experience of art helping you see beyond the limits of words, well, then, I guess one explanation could be that you are much better with words than I am.

It is not that philosophers have been unable to make use of literary writings. They have throughout history, and even philosophers nowadays who consider themselves analytic borrow from literature. But I suppose what Professor Bottici is getting at is that philosophers typically don’t think they could do philosophy in the form of fiction or poetry or myth. Is she right? And if so, is it a problem?

The transcript of the talk is here.

Bonus points for commenting in the form of a poem.

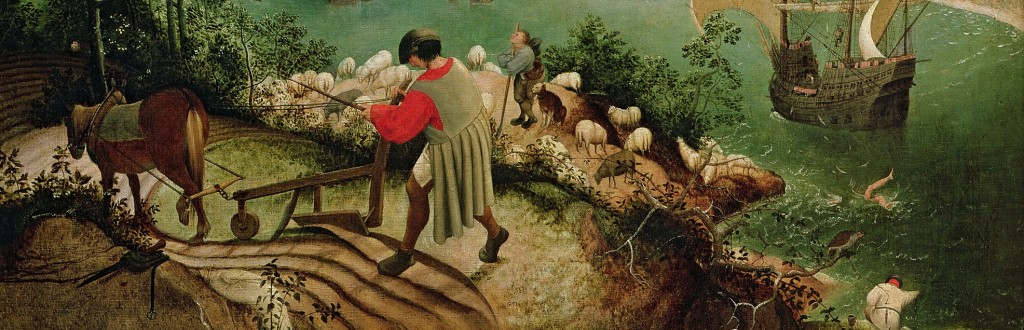

(image: detail of “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus” by Pieter Bruegel the Elder)

I’ve found that certain literary works can sometimes help me to keep philosophical inquiry in perspective, so I don’t take what we do as philosophers more seriously than I should.

I won’t write a poem here, but I will quote one or two that had a profound influence on my early thinking and on my attitude toward philosophy as a discipline.

Though the air is full of singing

my head is loud

with the labor of words.

Though the season is rich

with fruit, my tongue

hungers for the sweet of speech.

Though the beech is golden

I cannot stand beside it

mute, but must say

“It is golden,” while the leaves

stir and fall with a sound

that is not a name.

– Wendell Berry, “The Silence” – http://vox-nova.com/2009/08/18/wendell-berry-the-silence/

And then this:

i mean that the blond absence of any program

except last and always and first to live

makes unimportant what i and you believe;

not for philosophy does this rose give a damn . . .

– e.e. cummings, “voices to voices, lip to lip” – http://www.sccs.swarthmore.edu/users/03/cdisalvo/cummings2/voices2.html

I have even tried my hand at spoken-word performance, though I won’t claim it ascends to the status of a literary work: http://ethicsafield.com/2015/01/02/ethics-lesson/

As Plato demonstrates, there is no reason in principle why a work of literature can’t be worthy of study as philosophy. Having said that, I don’t find a lot of argument in most fiction, poetry or myth. Fiction and poetry are good for stimulating ideas and myth can provide important insights into a people’s beliefs and values. All are worthy of a philosopher’s attention. Still, there is no substitute for reasoned argument.

Argumentation is important, but rhetorical sophistication greases the wheels and gets the argument moving. Perhaps better engagement with literature would help clarify and communicate philosophical arguments, allowing philosophers to argue more efficiently and forcefully.

yes justin, your supposition is correct. that’s what i was getting at. i am puzzled by the fact that, although the transcript of the talk has just been published, i have already received a bunch of emails of people interested in it. does it mean that the question has become particularly timely? i think so. as the digital medium opens up new possibilities of writing (and thinking), we are forced to rethink our inherited forms and maybe find out that they were not the best possible ones…

I’ve occasionally wondered if storytelling might be a more efficient method of explaining concepts. It may not help much by way of argument, of course.

Sometimes philosophy is written in verse. Think of Mandeville’s Fable of the Bees, or Pope’s Essay on Man. At other times, poetry can be particularly philosophical. Blake comes to mind — he’s rigorous and transparent and seems to be giving arguments (he’s got some strange views though). These are examples from a few centuries ago. I suspect that the clean divide between philosophy written in non-fiction prose on the one hand and philosophy written in verse or in an explicitly fictional context on the other is a pretty recent development.

I’m thinking about Vasily Grossman’s “Life and Fate” as deeply infused with philosophy or, perhaps, philosophizing. Or, continuing with more Russians, parts of Dostoyevsky’s “The Brothers Karamazov,” namely the Grand Inquisitor parable? Such examples may even, arguably, follow forms of reasoned argument. Are they acceptable marriages of literature and philosophy?

Perhaps Straussians would cheer the esotericism of such forms…

It’s notable that many of the responses here assert or assume the primacy of “reasoned argument” in philosophy, and that on an set of assumptions about argument and about reason that necessarily exclude narrative, metaphor, and sundry tropes of literary expression.

I could point out that even forms of expression that present themselves as a set of bare propositions that, joined together, build up to a rigorous argument are nonetheless full to the brim with metaphor. (Count the metaphors in that last sentence . . . starting with “point out” and including the term ‘metaphor’ itself. Regarding this point, I would point out Lakoff and Johnson’s excellent book, Metaphors We Live By.)

I could also point out that some forms of argument draw heavily on analogy or example, or turn on distinctions best drawn by telling a story.

More than this, though, asserting that philosophical inquiry must always and only come down to “reasoned argument” begs the question of what does and does not count as “real philosophy” . . . a question that, as far as I can tell, has not been and may never be settled to the satisfaction of everyone or, indeed, anyone.

Another goal of philosophy might be to elucidate aspects of human experience that elude straightforward expression, or to draw attention to values that are not just lying around like logical pebbles on a rational beach to be collected and counted, or to voices that might not be heard except through the stories they tell. For all of these things, various kinds of expression other than rational argumentation, expressions that might be classed as “literary”, may not only be acceptable but even necessary.

But even leaving all that aside, leaving aside even the fact that many readers of this comment will instantly brand me as “one of those Continental types” – not strictly true, but a label I can live with – I would suggest that literary works may be indispensable for teaching philosophy, perhaps especially practical ethics.

One of my goals as a teacher is to help students learn to discern moral values that may be at stake in complex human situations, situations full of uncertainty and open to multiple interpretations, situations in which choice and action may be multiply constrained by the workings of systems and institutions. I’ve been experimenting with a way to help them live through such situations without actually having to live through them: they have been writing and acting out scenes, setting up a situation and showing how three different endings would play themselves out. It’s too soon to tell, but the students’ reactions to their projects have been quite positive; if nothing else, they’ve remained actively engaged in the hunt for instances of value.

To take another example, I regularly use Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac as the basis for my environmental ethics courses, but not for the reasons many philosophers would think to be obvious. I know there is heated controversy over this point, but I don’t see Leopold as offering an argument for a moral theory in his brief comments on “the land ethic” at the end of the book. What interests me more, and what I have my students work through and reflect on, are the stories that make up the first two sections of the book, stories in which Leopold exhibits a finely tuned imagination for the workings of systems and for the ways in which the systemic effects of human choices intersect with the lives and fortunes of other people and other living things.

In a brief story on culling trees from a woodlot, Leopold can contribute more to students’ understanding of the world and their place in it then I could contribute by a month of lectures structured in terms of formal argumentation.

Is this not more ‘Analytic’ or ‘Anglo-American’ Philosophy’s exclusion of Literary writings, rather than Philosophy full stop. Continental/European Philosophy generally does not really have this problem. Non-western philosophical traditions generally do not have this problem. In fact, isn’t the status of literature and the arts and ‘literary’ or ‘mythic’ style one of sources of the so-called analytic/continental divide and ‘Anglo-American’ Philosophy’s general dismissive attitude towards non-western philosophical traditions?

Although I’m a continental philosopher, I hate to see this question devolve into team sports again. To be sure, continental philosophy, historical philosophy (i.e. philosophy before the divide), and non-Western philosophy have a more overtly positive relationship with literature and the arts. At the same time, however, their integration of art and philosophy often preserves the boundary between the two.

In Taoist texts, for example, stories are often subordinated to a larger structure of argumentative reasoning, even if that reasoning is (like some ancient and Hellenic philosophy, like Kierkegaard, like Wittgenstein) aporetic, skeptical, or designed to get us out of reason by way of reason. In the use of dialogue in Plato, Hume, Dostoyevsky, Sartre, and others, the line between the literary and the philosophical is still quite clear and the implicit assumption that reasoned argument is primary is not called into question.

So, if some think that assumption *should* be called in question, it’s still false to assume that continental, historical, or non-western philosophy are not implicated. I’m also at a loss to understand why and how that assumption should be questioned. To ask why should we make reasoned argument primary is to demand a reasoned argument. It makes more sense to ask: why such an overvaluation of reasoned argumentation to the exclusion of artistic methods?

To my mind that makes better sense of the long history of this problem, beginning with Plato, a poet who bans the poets while writing poetry about Socrates who is, in turn, a philosopher who claims that truth is ineffable by effing never shutting up about it. One aspect is, surely, that it’s a defensive gesture: philosophers know we’re much closer to literature than we’d like to be, so we distance ourselves from explicit practitioners to avoid remembering this (Baudelaire: “hypocrite lecteur, mon semblable, mon frère). This is also surely the basis of Socrates’ obsession with the Sophists: their uncomfortable similarity.

But in Plato and Socrates’ defense (and of all philosophers who think there’s a meaningful difference, if not a strict line, between art and philosophy), they aren’t just in denial. Plato’s dialogues are full of critical self-awareness about his appropriation of art. In places, the philosopher is portrayed as using a counter-spell, an irrational magic turned against the irrationality of magic. In other places, Socrates is very explicit that we turn to metaphor and image out of necessity, implying philosophical language is ultimately as metaphysically suspect as artistic representation, with the important difference that it admits to it. To be blunt: we have to seduce people away from seducers, lie them away from liars, a position that doesn’t reject the divide between reason and myth.

And, of course, we always fail to notice that Socrates does not ban the poets. First, he temporarily bans them, allowing for a reversal if a sufficient argument is made on their behalf. Second, he bans only imitative, deceptive poets, those intent on convincing their audience that their imitations (mostly mythical stories about religion and social values) are truths. (For a bit of historical context, one way of looking at it is, quite frankly, that he bans religious and political indoctrination in schools, which hardly makes him an enemy of the arts.) Plato’s objection to the poets is not that they are poets but that the poets of his day happen to be dishonest, misinformed, and overly revered poets given a high degree of moral, social, and political authority.

Achille Varzi and Claudio Calosi recently published a book-length philosophical poem in medieval Italian: Le Tribolazioni del Filosofare. They’re working on a translation into English.

They do a reading on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=20NBGrcc1ug

Their abstract: “A scholarly annotated epic poem on the pitfalls and tribulations of “good philosophizing”. Divided into twenty-eight cantos (in medieval Italian hendecasyllabic terza rima), the poem tells of an allegorical journey through the downward spiral of the philosophers’ hell, where all sorts of thinkers are punished for their faults and mistakes, in the endeavor to reach a way out of the condition of intellectual impasse in which the narrator has found himself. The affinities with Dante’s Inferno are apparent. Whereas Dante’s poem is about human sins and moral felonies, this one is about philosophical errors and fallacies; whereas Virgil takes Dante through the gluttons, the wrathful, the violent, the traitors to parties and countries, etc., here Socrates takes us through the realists, the skeptics, the dualists, the nichilists, the worshipers of language and easy mythos, etc. And yet this is not just a philosophical counterpart of Dante’s masterpiece, even less a parody. We can’t say exactly when, how, and why it was written, but this is an authentic piece of philosophy, a poem of love, a passionate testimony of militant metaphysics. It is the inspired and inspiring journey of someone, anyone, who is truly moved by the Love for Wisdom and by the grueling purification of the intellect that it demands.”

“A scholarly annotated epic poem on the pitfalls and tribulations of “good philosophizing”.

This reminds me of my own answer to the question: why should philosophy overvalue reasoned argument to the exclusion of artistic methods?

In principle, there’s no reason, but in practice:

1. Philosophers are often lousy artists.

2. Art is, ultimately, a higher, more valuable activity than philosophy, so it’s not worth ruining art to improve philosophy.

I mean, have you *read* Nietzsche’s poems?

Thanks for that link. The talk looks really interesting.

I don’t really see philosophy (even analytic philosophy) overall as mytho-phobic. Even Plato’s Socrates did not ban all the poets and Plato himself gave us a number of primal philosophical myths within the context of dramatic dialogues as well as introducing various metaphors whose metaphorical origin is now forgotten. Nietzsche? Kierkegaard? Interpretations of Antigone and Bartleby seem nearly de rigeur for Continental philosophers. In analytic philosophy Bernard Williams might be a special case, but he surely made use of literature in his work. Wittgenstein’s later work has a certain literary quality. Many thought experiments could be read as philosophical myths, although it is telling that some (trolley, veil of ignorance) have been attacked precisely for being unreal/fictional scenarios. The point about philosophical “logocentrism” was made by Derrida and others long ago. Perhaps it is worthwhile to ask the question again within our different philosophical milieu. I quite like the work of Machiavelli and think his philosophical use of history (e.g., Commentary on the Ten Books of Livy) shows that really interesting political philosophy can be developed from reflection on and interpretation of historical events. How historical narratives might differ from fictional ones and what that means for their philosophical use is also an interesting question. Using historical narratives would seem a lot messier if only because a well-formulated myth is probably easier to domesticate for philosophical purposes than a history in which facts as well as interpretations and causal claims will be endlessly debated.

“Many thought experiments could be read as philosophical myths”

This is an intriguing comparison, especially given the fact that for Socrates and Plato, there were good and bad usages of myths, where the bad ones mislead people into thinking they’re not myths at all.

For example, is trolleyology, at least when used to confirm philosophical positions by appeal to intuition (which is, at bottom, by appeal to unconscious social authority of the kind Socrates attacked), a paradigm case of the bad use of myth?

Is philosophy, especially some forms of so-called analytic philosophy, in a sense, not mytho-phobic enough?

(For the record, I can think of continental cases of bad use of myth, too! I just want to reject the “continental=art=good, analytic=non-art=bad” dichotomy. After all, even the the history of art makes room for artistically valuable cases of “anti-art”!)

I troll philosophy for my poetry, often quoting philosophers, mostly, for some reason — or none, in the H’s.

“The possible ranks higher than the actual.” Martin Heidegger

Haboob

Tout de meme

the desideratum of

the golden glove,

the idiocy of my love —

our love, were it to occur —

the song of it echoing across bridges,

between banks of river gorges,

carried along in barges, aloft sine waves,

tunneling through mountains,

plummeting down canyons for millennia,

bruising grasslands

and

burrowing into all the libraries of the world

forgotten about through the ages,

unearthed by sages to deride and malign

and yet marvel —

marvel at our dasein.

Merilyn Jackson 2013, published in Columbia’s Catch & Release, 2014

The question “Why should philosophy overvalue reasoned argument to the exclusion of artistic methods?” is only going to be interesting to people who are already convinced that philosophy overvalues reasoned argument. The question seems to leave the issue that divides us untouched.

Greg, I’ll admit I’m not satisfied with the question. But it was mainly meant to be a less contentious, more modest version of the questions others had posed–e.g., why does philosophy “exclude” literature (it clearly doesn’t) and why assume the primacy of reasoned argument in philosophy? (a fruitless, contradictory question).

We might “overvalue reasoned argument” in the sense that we overvalue its *appearance* as certain stylistic conventions. But even so, it’s not to the exclusion of artistic methods, given the many counterexamples mentioned in the thread.

Maybe instead: why is philosophy overly suspicious of art and literature? This variation would allow that it doesn’t exclude the arts and that it rightly gives priority to reasoned argument.

Arguably, Plato thought he could, and sometimes should, do philosophy through literature. (Otherwise, the Symposium would’ve ended with Socrates, not Alcibiades.) So did Rousseau, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and maybe Murdoch. Proust and (late) Wittgenstein have more in common with each other than they have with most other novelists or most other philosophers.

Philosophy that should be assigned in (most) courses, or published in professional journals, is not done through literature, though I suspect that this has more to do with (perfectly justified) norms about courses or professional journals, rather than with the nature of philosophy per se.

I think it’s quite unfair to analytic philosophy to say that it shies away from dealing in myth. Almost all of the claims and evidence mobilized in analytic philosophy are mythical.

“Is it to reinforce the idea that philosophy concerns arguments, reason, the logos, whereas fiction concerns stories, metaphors, and myths…? But has philosophy ever liberated itself from myth? And even more so: does it even need to do so in the first place?”

Yes, yes, and yes.

Socrates said he was waiting to hear

An answer to whether it’s useful to see

The world through reflections that are poetry

Or whether it’s better to lay it out clear.

He’s waiting, with Glaucon, it’s poetry’s turn

To argue with Socrates: good for the soul

Or pretty fake shadows obscuring the goal?

The question’s still open, they’re eager to learn.

Tolkien would explains that all art can still save,

It isn’t mimesis, artists subcreate,

Art comes round corners to help us be great

Grabs us hard by the soul and heads out of the cave.

So would you learn wisdom learn virtue, do well?

Art’s the friend at our side as we try to excel.

Footnote, since this is academia, Tolkien said this in “On Fairy Stories”, 1939, and I really do think his concept of subcreation is what Plato needed.

Three thoughts:

1. I’m with Justin that “good philosophy generally aspires to a kind of rigor and transparency that is hard to imagine being present in good literature.” The exception that proves this rule is Lucretius’s De Rerum Natura, a work which is phenomenal poetry and contains many tightly reasoned arguments.

2. Chiara Bottici’s representation of Plato isn’t quite right. Plato draws the distinction between logos and muthos early in the Phaedo when Socrates’ friends discover him composing poetry while in prison. Socrates says that the poets make stories (muthoi), not arguments (logoi) at 61b. It seems very clear that logoi concern what we still recognize as arguments: precisely stated premises and a conclusion. The Phaedo, like many dialogues, then ends with a myth; of the myth, Socrates says that “No sensible man would insist that these things are as I have described them…” (114d). There are no arguments in the myth; Plato seems to use it to try out various themes (such as our place in the cosmos). Plato deploys myths with similar themes in the Phaedrus and the Republic, although the details of the myth differ between them. It at least seems clear that Plato wants us to extract big themes from his myths, but he is instructing us not to put pressure on the details (and hence not to treat them as arguments).

Moreover, I fear that Bottici has misconstrued the Republic. Plato bans the poets, but he does not ban poetry (only certain kinds of it are banned). Mythos plays a very important role in his kallipolis: they are falsehoods in words (382a-d) used to instruct to the non-philosophers, e.g. the myth of the metals.

3. Aristotle seems to think that muthoi are driven by the same impulse as philosophy: “And a man who is puzzled and wonders thinks himself ignorant (whence even the lover of myth [philomuthos] is in a sense a lover of Wisdom [philosophos], for the myth is composed of wonders); therefore since they philosophized order to escape from ignorance, evidently they were pursuing science in order to know, and not for any utilitarian end.” (Metaphysics, 982b17-19 or thereabouts) The difference, I think, is that Aristotle expects the mature philosopher to move past muthos in order to attain the “rigor and transparency” (quoting Justin) of logos.

This is just reporting on my probably naive conception of philosophy, but here goes:

I thought what we are doing in philosophy is getting at the truth. Ideally, stating the truth in such a way that we rid ourselves of all of the reader’s context and present the truth as pristine and sterile as we possibly can. We are hindered and burdened by the baggage of natural language, but to be as clear as possible and not talk past each other, we do our best define our terms in such a clear way that we all end up having the exact same concept in mind.

Literature does the very opposite. It, like art, plays on the fact that we are all subjects with unique histories that bring our own stories to the text, and thereby create a new story for every perspective from which it is read. I don’t at all doubt the value in this enterprise, but I hold out hope that unlike knowing what it is like to be a bat, I can know what it is like to be you, and if you tell me what the story reads like from your perspective in such a way and with such words that I can fully understand what you are reading, then I will truly know. But if you do that, and you sterilize your words and anesthetize the biotope of language to a degree that we both have the same concept in mind when we see the same word, then, and only then, have we gone beyond literature and done philosophy.

So no, I do not think that literature can ever be philosophy. That is because the language of fully defined unambiguous terms, probably more logic than English, just makes terrible prose.

A story is simply a character we care about overcoming great obstacles to achieve some worthwhile goal. A good journal article has essentially the same structure. The author starts by “motivating the project,” which is basically making us care about the character and the character’s goal. The character might be some theory (Can utilitarianism overcome the DEMANDINGNESS objection? Buh-buh-BUM!), or the set of all philosophers, or humanity itself (How can we ever solve the white dress/blue dress problem? Oh noes!). The author brings out how challenging the obstacles are. The author helps the character overcome the challenges. There’s even genuine suspense. Sure, the thesis statement is up-front, so we know the “ending” of the story, as it were, but so do we know the ending of lots of gripping tales in literature. The suspense is in anticipating how the ending will be reached. How will the obstacles be overcome?

Granted, a story is not literature, but what turns it into literature? Beautiful, evocative language and deep insights? If so, then some of the best philosophy articles would clear that bar.

Well…

1. Intuition pumps;

2. Acquaintance knowledge via empathetic imagination;

3. Provision of counterexamples to universal assertions hitherto unassailed.

For a start.

There are obviously important and difficult issues here. As Eva Dadlez suggests, especially in #2, there may be some domains of knowledge

in which it is *not* properly conceived of as “pristine and sterile” (as naive grad student puts it): for example, apt second order evaluation of what it is worthwhile to desire or pursue, or of what social-political-institutional commitments are (more) worth having is arguably something that cannot reasonably be done without emotional attentiveness to what the facts of a situation mean to and for us. (Emotions have, after all, a cognitive component, on almost all accounts.)

It may interest those who have followed this thread so far that Oxford University Press is undertaking a series—Oxford Studies in Philosophy and Literature–in which each volume will be devoted to a single, major literary work. Original essays by a mixture of philosophically-informed literary scholars and philosophers with literary interests and skills will address how the literary work addresses and ‘worries’ at philosophical problems without quite solving them neutrally and conclusively. Understanding how literary texts do this can help to modify our sense of what might count as plausible fullness of address to these problems. Volumes on Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler, Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Shikibu’s The Tale of Genji, Dickinson’s Collected Poems, Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, and Kafka’s The Trial are already in various stages of preparation. Anyone interested in this series is encouraged to contact me (the series editor) directly.

“Is it to reinforce the idea that philosophy concerns arguments, reason, the logos, whereas fiction concerns stories, metaphors, and myths…? But has philosophy ever liberated itself from myth? And even more so: does it even need to do so in the first place?”

MAStudent: “Yes, yes, and yes.”

I disagree on all three scores. First, Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground, for instance, deals with the very nature of reason and logos (and concerns a “classic” philosophical problem, viz. free will). It also proceeds by way of arguments from a particular character. Its themes are inextricably tied up with the philosophical perspectives explored by its character. Similar things can be said about the Platonic dialogues and the writings of Nietzsche (and Dostoevsky’s other writings of course).

Second, philosophy has not liberated itself from myth. As others have rightly noted, analytic philosophy relies heavily on imaginative thought-experiments, analogies, and metaphors to forward arguments. In other words, like literature, it uses fiction (and more specifically, science fiction) to get at the truth.

Third, philosophy does not need to rid itself from its reliance on analogy, metaphor, and fiction. Why? Because these are very useful tools for communicating complex ideas (although not always). This is the very reason it has been the domain of philosophers and poets for centuries.

We might ask, where are the dividing lines, then? I would say they aren’t sharp. It’s just that the goals of any given work of literature or art may not be exclusively philosophical, and any given work of philosophy may not be most effectively communicated through literary means. As such, literature may not always be especially philosophical, and philosophy may not always be especially literary.

One hallmark of all literature (poems, novels, stories, plays, etc.) is that literary works draw attention to their form. They are things made of words that draw attention to the thingness of language itself. Because language-as-object is incommensurable with the type of “objectivity” that many philosophers say they strive for (in which language becomes a transparent, pliable and controllable tool), philosophers call literature “unserious” or otherwise claim that it is “not really language” (although literature is language most itself). Philosophers who recognize the importance of language’s object-ness (rather than its “objectivity”) are not in the habit of attacking literature.