Rise of the Intuitions

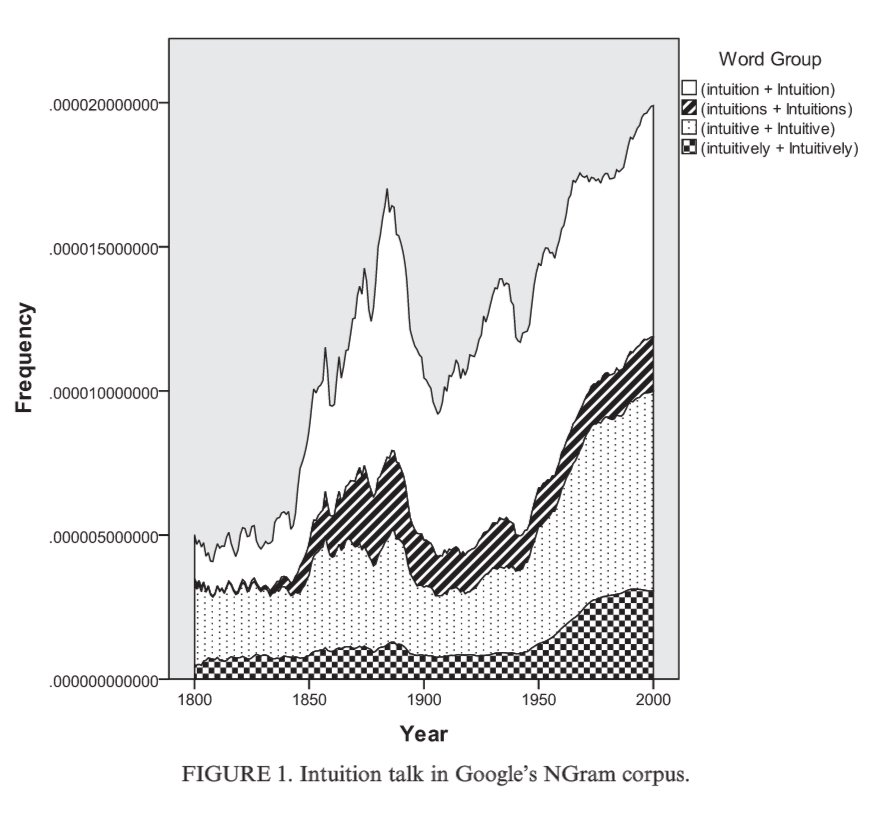

Is there a word more overused in philosophy nowadays than “intuition”? That is many people’s intuition sense of things, but why go with gut feelings when there is data? That’s right: data. James Andow of the University of Reading has just published findings on the use of the word “intuition” and its variations in an article in Metaphilosophy entitled “How ‘Intuition’ Exploded.” Indeed, there is more “intuition talk” now than ever. He notes:

The proportion of philosophy articles indexed in JSTOR indulging in intuition talk has grown from around 22 percent in the decade 1900–1909 to around 54 percent in the decade 2000–2009.

Andow looks into how and where intuition talk grew, in the hopes of providing the data that any account of its growth would need to explain, noting that different explanations might generate different thoughts about relying on or referring to intuitions in philosophical work.

One thing he notes is that in general—not just in philosophy–there has been an increase in the use of “intuition” and the like:

Popular usage and usage in other disciplines has also increased:

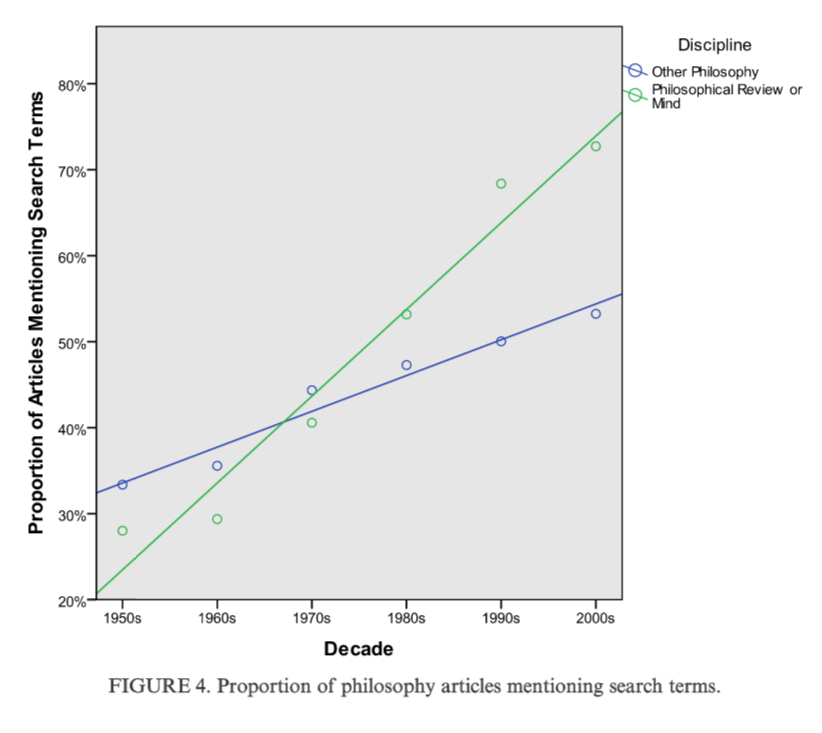

Additionally, within philosophy, the increase has been sharper in “analytic”-style philosophy, as represented by “staunchly analytic” journals Philosophical Review and Mind:

He notes: “In the 2000s, 86 percent of articles in Philosophical Review engaged in intuition talk.” (!)

Towards the end of the paper, Andow discusses possible explanations for the rise in intuition talk, including: correlations with certain psychological traits that seem to be on the rise in the general population (such as extroversion and narcissism), the fragmentation of academic research into relatively homogeneous communities that have shared intuitions to refer to, and the increase in the proportion of female academics. He emphasizes that these are mere suggestions and that further research is needed for an accurate explanation of the data. Your thoughts are welcome.

I know the author was being cute at the beginning, but it still seems sloppy to equate intuition with “gut feelings,” or to treat data and intuition as interchangeable. A more robust and historically rooted sense of intuition treats it as the sense of how our hypotheses map onto available data. So intuition actually assumes data, and it doesn’t seem to be merely a feeling, nor something we no longer need once we have data. It seems at least related to the ability to see meaningful patterns.

But now I’m just becoming part of the data to which this article refers.

The claims by Goldman, Hintikka, and Cohen quoted at the start of the paper — that early analytic philosophers didn’t use the term “intuition” to refer to a philosophical methodology — is bizarre if analytic philosophy includes analytic moral philosophy (and how could it not?). The moral philosophers of that period repeatedly spoke of intuition. Sidgwick said he differed from Bentham and Moore in recognizing that utilitarianism has to rest on a “fundamental moral intuition,” and proposed tests to distinguish genuine intuitions from mental states that appear to be such but aren’t. Rashdall, Moore, Ross, Broad, and Ewing likewise appealed explicitly to “intuition.” For this reason they’re regularly called … are you ready? … “Intuitionists.” (They also thought key truths in mathematics and metaphysics are known by this method.) The paper in effect gets this, noting that the term was indeed used in the early 20th century. But I think its methodology, of looking only for “intuit” and its cognates, underestimates this fact. In that period much more than today, philosophers used other expressions as equivalents to “intuition,” speaking e.g. of the “immediate apprehension” of truths and, even more often, of the truths one intuits as “self-evident.” Because the latter term is, I suspect, much less common today, a search that included “self-evident” and its cognates would, I predict, find less of an increase from the early 20th century to today than the paper’s current graphs do.

I think it’s a hit. Intuition is a method. Embraced by many, and feared by others as it calls upon your courage and faith – in yourself, in what you “feel” is right, is true… Maybe like walking on the water or on the clouds, or staying in midair, for someone who needs to feel the “firm ground”. It’s true though that intuition led to many discoveries, be it an “idea” to make an experiment differently – and suddenly the result appeared and things were more clear… Intuition may be like opening a window and letting the Unknown in…

As someone currently in the middle of working on a paper on intuitions, I was very pleased to see this article.

One thing that’s interesting to note, I think–and this connects up with Professor Hurka’s comment above–is that talk of intuitions seems to have been pretty robust in early 20th-century ethics, but other philosophers didn’t really start talking about “intuitions” qua “judgements in response to hypothetical scenarios” until more recently; the 70s, maybe? (I need to do more research on this) One “intuition” that has been of much focus is the “intuition” one gets in Gettier cases. Interestingly, Gettier does NOT make reference to “intuitions” at all in his famous paper, he simply takes it as obvious that in the situations he describes it is not true that the person in question has knowledge. Its redescription into a case of “having an intuition” must have come later–but again, how much later, I do not know.

Personally, I have been trying to eliminate the word from my philosophical vocabulary (with the exception of the aforementioned paper!), because I think it does more harm than good, and we’d be better off distinguishing different kinds of things we might be talking about when talking about intuitions: hunches, guesses, inclinations to believe something, our pre-reflective beliefs, and so on. As to the methodologically-common “intuitions in response to hypothetical cases” sense, I reject that, for reasons which I won’t get into here because this is a blog comment thread and not my paper on the subject. But I think studies such as the one considered here are useful for getting us thinking about *why* we talk the way we do when doing philosophy, and whether or not we ought to.

If the appeal to intuition is problematic, the solution isn’t going to be to stop using the word. The methodology has been in place since Plato (or earlier), and not just in moral philosophy. (Think of Reid’s critique of Locke’s account of personal identity–the Brave Officer..) As Tom points out, philosophers have just used different terminology. Sometimes it’s a synonym like ‘immediate apprehension’, or it can just be a phrase like “it seems obvious that…’ or ‘we all believe that…’ or ‘it seems clear that…’ Most or maybe all of the free will debate employs this methodology.

Again, I’m not sure it’s a problem , assuming we recognize that that’s what we’re doing.. In ethics (and probably many other subfields as well), we can’t come to ‘all-things-considered’ judgments without appealing to intuitions at some level. So maybe it’s a good thing that we’ve started to be up front about it. Nothing is more irritating than when people say they’re just using ‘reason’ to derive their conclusions, but implicitly relying on controversial core intuitions and drawing inferences from that.. (Consequentialists seem to be doing this a lot lately.)

My suspicion — though not an intuition — is that this reflects a growing honesty. It seems that all arguments, philosophical or otherwise, are based on intuitions. The main difference seems to me — and this IS an intuition — to be that (analytic) philosophical arguments are generally better at (1) acknowledging their intuitive claims and inferences, which requires (2) them to first identify their intuitions, if only to themselves; and that (3) “good” philosophers are well ahead of most other fields, particularly humanities and social sciences (and the many “not so god” philosophers), at ensuring their intuitive moves are less controversial than their conclusions. All of which opens metaphilosophical questions about the value of intuition, the epistemology of intuition, etc. Now, I don’t mean to disparage much of the writing in these other fields for the simple fact that if the writers spent much of their time asking about their intuitions, they would drift into philosophy instead. One hope I have is that good philosophical work on intuition can help all fields refine their use of intuitions accordingly.

Hi David,

“My suspicion — though not an intuition — is that this reflects a growing honesty. It seems that all arguments, philosophical or otherwise, are based on intuitions.”

I’m curious to know what you mean by ‘based on’. Is this (a) the idea that the whole rational force of a reason or premise in reasoning derives from a supporting intuition or (b) just the idea that for any premise or reason that figures in reasoning there is, among other things, an intuition that supports it? If it’s (b), then it seems that intuition is on par with things like our experiences, beliefs, or our brains. That weaker reading seems fine, but it’s hard to see how honesty speaks in favor of acknowledging this kind of dependency. (Of course if someone is offering an argument, they’re using their brain, but I don’t think that it’s important from the point of view of honesty to acknowledge this in offering our arguments.) If it’s something stronger like (a), then I think that it’s a really problematic epistemological claim. (On this reading, it seems akin to the claims about seemings that Huemer and other phenomenal conservatives have defended on which all the seemings offer some kind of positive rational support to beliefs with matching contents no matter how perverse, confused, or muddled those intuitions/seemings are. (Probably not the most neutral description of that project.))

I have the opposite suspicion from David’s. It’s that “intuition” is used because it suggests a distinctive faculty whose deliverances ought to be given some special respect, but in reality we’re just talking about reliance on ordinary beliefs for which no further support is being given. (I think I remember Peter van Inwagen saying this in one of his papers, or maybe it was just in a seminar.) Not that there’s always anything wrong with doing that, of course.

[In reply to Celina Durgin] Did you actually mean “interchangeable” in your first sentence? Because it seems the beginning of this post is suggesting that data and intuitions are *not* interchangeable (and, if anything, that they are mutually exclusive–though I don’t think the post actually goes that far). In any case, it seems to me that gut feelings assume data, too, since there needs to be something for the gut feelings to be about. It might be a much smaller data set–indeed, so small that we might feel uncomfortable calling it data (as the saying goes, “the plural of anecdote is not data”)–but the same can be said about many of the data sets upon which intuitions are based. People sometimes form intuitions based on single cases, after all (e.g., arguments based entirely on a single intuition pump). And of course, if intuition didn’t *seem* like merely a feeling, we wouldn’t be so inclined to follow it. But that’s how all insidious patterns of reasoning operate: they masquerade as innocent. This isn’t to say that using intuitions is an insidious pattern of reasoning, but only to say that it seeming not to be is not much comfort.

“One of the things we ought to have learned from the history of moral philosophy is that the introduction of the word ‘intuition’ by a moral philosopher is always a sign that something has gone badly wrong with the argument.” (Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue)

But I wonder how quickly we should move from “the word ‘intuition’ and its inflected forms are appearing more in philosophy papers” to “philosophers are indulging in more intuition talk.” Here’s a possible case where the first is true and the second is not: Influential Philosopher A indulges in intuition talk. Influential Philosopher B disputes Influential Philosopher A’s argument without himself engaging in intuition talk but does quote Influential Philosopher A’s intuition talk. Other philosophers (influential and otherwise) start discussing the disagreement between Influential Philosopher A and Influential Philosopher B, only some of which indulge in their own intuition talk. Thus we get a whole slew of papers containing the *word* “intuition” (and its inflected forms), only some of which are indulging in intuition talk.

Here’s something I’ve learned from the history of moral philosophy: when someone like Alasdair MacIntyre claims that he’s not relying on moral intuitions that’s always a sign that something has gone badly wrong with the argument.

What does more females in academia have to do at all with increased “intuition” talk?

It certainly has increased. Though it is very important to distinguish two main uses of the term. The first use is as direct evidence: “it is intuitive that p therefore the probability of p is increased”. This is obviously the controversial use. However, I suspect the majority of the uses of the term ‘intuition’ occur when an author gives a clarificatory remark or attempts to set up a problem or argument in less technical terms: “intuitively, one might understand p in the following way…” This latter use of the term is almost completely innocuous.

I think by “interchangeable,” I referred to the idea that once we have data, we no longer need intuition — that we can “change out” our intuition for data. But thanks to your post, I realize that “interchangeable” was a very unclear word to use in order to convey this idea, which you referred to thus: “If anything . . . they are mutually exclusive — though I don’t think the post actually goes that far.”

I get your point about insidious patterns of reasoning, though I’m not sure I understand your point that “if intuition didn’t *seem* like merely a feeling, we wouldn’t be so inclined to follow it.” It seems that if intuition *did* seem like merely a feeling, we would’t be so inlined to follow it, at least, and especially, in serious academic philosophy. I would also maintain, based on my notion of intuition, that dataset can be large enough to obviate intuition, because data must be interpreted. The hypotheses, and eventually theories and laws, we impose upon data are our best way of explaining the data. If we use a standard of simplicity or explanatory power to rate our theory, we ultimately rely on some sort of intuition about why these standards are good. And even given that explanatory power is a good standard, there isn’t always an obvious way of concluding which explanation actually explains more phenomena.

That’s my thinking about the issue. It still leaves open the question of what precisely intuition refers to, particularly in terms of an innate cognitive ability.

that *no dataset can be large enough

Herman Cappelen wrote a persuasive book on this topic. It’s called “Philosophy Without Intuitions,” Oxford, 2012. (And, although I like to remain anonymous on philosophy blogs, I assure you that I am not Herman Cappelen. I know nothing about him except the book).

Celina: Yeah, that should have said “if intuition *did* seem like merely a feeling” or “if intuition *seemed* like merely a feeling.” Boo for typos. In any case, my point is just that I’m not willing to take an intuition that intuition is reliable at face value. It’s similar to the Humean point about induction: if all the evidence for induction is inductive, we haven’t really justified induction. Maybe we have no choice but to reason inductively, but we should maintain a healthy skepticism about it. And while we may similarly be stuck using induction in some places, it’s worth maintaining a healthy skepticism about it as well.

As for data requiring interpretation, it’s not clear to me that we ought to use intuition as anything more than a way of deciding which possible interpretations to investigate first. We have a data set, and it could be explained in, say, 100 different ways. Ten ways seem plausible to us, so we look at those first. But if none of them are sufficiently explanatory, we start looking at the other 90. And even if one of them *does* seem sufficiently explanatory, we should still be looking at the other 90. Our commitment to the one that seems sufficient should be provisional only. Certainly, a lot of people leave the other 90 alone once they’ve found something they like in the original ten. But I don’t see that as a strategy to be recommended.

Tom: Yes, there’s nothing like a little witticism to get upvotes and acclaim in this profession. Well done. But if we look at the actual passage in After Virtue from which that quote comes, we’ll see that MacIntyre isn’t denying that he ever relies on moral intuitions. He is discussing the limitations of such an approach. Context, dear boy.

JDV: I’m of the view that induction is a species of inference to the best explanation, so that you can actually avoid Humean skepticism. You don’t justify induction with induction, but rather, you employ induction as a tool when trying to explain phenomena. I think we *should* look for the best explanation among the 100, as you suggested. But the criterion for what counts as the best explanation, or even a sufficient one, is still in question, and something like the faculty of intuition seems to be involved in answering it. So more than just a tool for deciding which possible interpretation to investigate first, I might involve it in deciding which interpretation is best. It wouldn’t be the sole factor, obviously. But when a group of scientists, say, try to reach consensus on a theory, at some point they all have the same data and are all intelligent, so the consensus is a matter of a certain sort of *seeing* whether the theory seems good. But this is all vague and ultimately a huge issue.