Hobbies of Philosophers: Meg Wallace

For the second installment of our Hobbies of Philosophers series, I talked with Meg Wallace (Kentucky). Meg works on metaphysics and philosophy of language, and her philosophy is super bad-ass. But today we are talking about her other life as an equally bad-ass aerialist. I spoke with Meg about what aerialism is all about, how she got involved with it, and how she combines these two seemingly disparate aspects of her life.

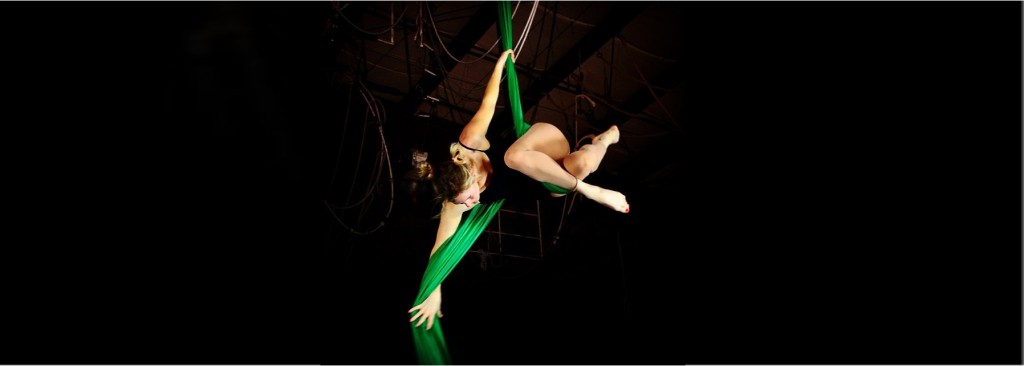

But here’s a description from Meg for the verbally inclined:

Aerial silks (also called aerial tissu or fabric) is an apparatus comprised of long strips of fabric suspended from above, usually from the ceiling (but sometimes a portable rig or other such structure). At our gym, the silks reach about 20ft high. Aerialists climb and manipulate the fabric, using it to assist in a kind of vertical dance. It is a combination of sport and art. Training and performing on silks takes a combination of strength, flexibility, grace, and courage. There is also the intellectual challenge of figuring out how to entwine yourself in intricate wraps and knots, without getting tangled up or falling out completely.

There are other aerial apparatuses I like to play on-–e.g., spanish web (or aerial rope or corde lisse), lyra (or aerial hoop), trapeze (both static and flying), etc.–-each of which is designed to highlight certain talents of the performer and requires specific skills. And there are non-aerial circus things I like to dabble in, too: I juggle a little and have just acquired my first fires fans (which are just what you think they are). But aerial silks are my favorite.

One of the neat things about the circus arts in general is that there is always some new apparatus or trick or skill to try. And given that these apparatuses and skills are weird and new, it is very likely that you will really suck at them when you start. But that’s sort of the point. There’s a very welcoming attitude in the circus arts, where everyone is encouraged to do these physically challenging, playful, non-practical skills, even if they’re silly and you’re really terrible at them. We do them anyway. And there’s a lot of laughter and cheering along the way.

If only we could all adopt this attitude and level of camaraderie in philosophy…

For the jealous among us, I asked Meg how one get involved in such a thing. Here’s what she had to say about that:

3(ish) years ago, my husband, Aaron, bought me a 6-week introduction to silks session for my birthday. I had seen pictures of people doing such things from time to time and thought that, because of my background of dance and yoga, I would love it. I didn’t realize at the time that I would become infatuated. I now train or teach aerials about 5 days a week.

In case it’s not clear yet why we should all join the circus, I asked Meg to try to narrow down (a) her favorite thing and (b) the most challenging thing about silks.

My favorite thing about silks is that very often—when doing drops, for example-–the goal is to wrap yourself in fabric, nearly 20 feet above the ground, hurl yourself headlong to the ground, and miss. It’s rebellion against death and gravity. It’s terrifying. And amazing.

The most challenging aspect of aerials is the combination of the physical strength it requires, with the intellectual challenge of manipulating yourself around the apparatus, all the while making it look as if it is the easiest thing in the world. Unlike many other sports, but very much like dance or the performing arts, the aerialist has to mask how much what she is doing hurts. The really incredible aerialists make it looks absolutely effortless. But they have the bruises and scars to prove otherwise.

Finally, I thought Meg would have some good thoughts about the relationship between aerials and philosophy, both in terms of similarities in how she approaches each part of her life and to what extent one is an escape from another. Before we hear from her about that please note that there is at least some overlap between her two lives, as Meg sometimes likes to impersonate modal operators:

Aerials and philosophy both require a lot of intellectual energy, confidence, and courage. When I am first learning a move in aerials, I can feel as mentally drained as when I am working on or presenting a philosophy paper. Also, I find that being in front of a bunch of smart philosophers, presenting my ideas, takes as much steel guts as hanging on to mere fabric with your bare hands 20 feet in the air.

Both require lots of hard work and practice. And they both give rise to that enveloping creative rush where you lose track of time and are surprised that hours have passed and that you forgot to eat dinner.

However, there are at least two important ways in which philosophy and aerials are different. First, very often when I am doing aerial moves that I know well, my mind is totally clear. I have no worries and I am (internally) very quiet and calm. In contrast, when I’m doing philosophy—even philosophy I’m very familiar with—my mind is a mad beehive.

This mind-clearing aspect of doing aerials has been particularly therapeutic for me. I have had a significant amount of personal loss in the last two years, so retreating to an activity where my mind can empty has been a welcome relief. Escaping by flying has contributed greatly to my mental well being.

I can relate to this, and it’s a large part of why I have a second life outside of philosophy myself. I recently participated in a sort of epic Facebook discussion about how to deal with the stress/difficulty/imposter syndrome surrounding philosophy, and almost everyone made mention of some kind of mind-clearing meditative activity being crucial to maintaining a kind of mental balance. Not everyone’s mind-clearing activities were as exciting as Meg’s, though.

As she mentioned, Meg teaches aerials too. And I got a cool bonus answer about the differences between teaching philosophy and teaching aerials, which seems like a good place to wrap up our conversation:

“When I am teaching aerials, especially to first time students, no one asks the question: Ok, fine, I see how you wrap the silk this way and that to do this super fancy move, but what is this good for? What can I do with this in the future? I’ve not heard a single person learning to juggle ask: Ok, I see that you have to do this and this to get the balls to all stay in the air, but what’s the point? How will this help me in my career?”

Maybe not all your readers will be aware of the background behind your two uses of the word “bad-ass” in the introduction. And maybe Wallace doesn’t want this background to be brought up any more, in which case feel free to delete this comment in moderation. But Wallace made a bit of a name for herself in the philosophical blogosphere about a decade ago, while still in grad school, for introducing the “wussy/bad-ass” distinction among philosophical views. Unfortunately, I can hardly find any unbroken links from 2004, but here’s a quotation that still exists:

http://torreywei.tumblr.com/post/7545250935/ive-currently-settled-on-three-elements-that-make