A Charmed Circle

The profession runs on reputation — basically the shared perception that you’re a smart guy. But how do you get reputation? Not by having a chair at a major school; that helps your visibility, but doesn’t protect you from being perceived as none too bright…. Nor does having the support of a powerful person do very much; you can be the favorite student of the top person in your subfield, but that won’t do more than get your foot in the door.

Instead, reputation comes out of clever papers and snappy seminar presentations. There are problems with that, which I’ll get to. But the point for now is that while it may seem like a vague concept, within each subfield everyone knows who the top guns are, and there’s a very steep slope downward from the few people at the very pinnacle and the next level.

Having sufficient reputation gets you into a charmed circle; as I wrote in that old essay, “In the modern academic world there tends, in any given field — whether it is international finance, Jane Austen studies, or some branch of endocrinology — to be a ‘circuit’, the people who get invited to speak at academic conferences, who form a sort of de facto nomenklatura. I used to refer to the circuit in international economics as the ‘floating crap game’. It’s hard to get onto the circuit — it takes at least two really good papers, one to get noticed and a second to show that the first wasn’t a fluke — but once you are in, the constant round of conferences and invited papers makes it easy to stay in.”

…It’s hierarchical; it can be very frustrating to people who haven’t managed to get in on the floating crap game.

That’s Paul Krugman, writing about academic prestige and its perks in his column in The New York Times. He focuses, naturally, on economics, but I would imagine that some readers see a “charmed circle” in philosophy, too, even if its entry criteria differ from economics. (via Mark Alfano)

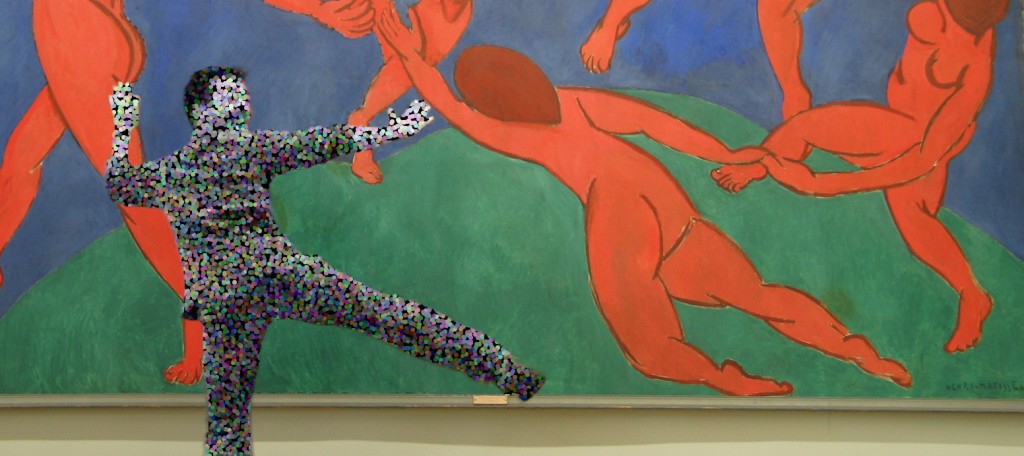

(art: photo of Dance by Henri Matisse with patron at The Hermitage, via Kevin Winston, altered)

There surely are plenty of charmed circles in academic philosophy, but my sense is that in philosophy, “having the support of powerful persons” or having a tenure-stream position at a major school goes a very long way towards being granted access to these circles. One need only consider the extent to which the proteges of famous people have access to networking, to being invited to contribute to OUP or CUP volumes, etc.

If anything Krugman underplays the role of patronage. *Merely* a foot in the door? In philosophy that means being hired as an ABD at a great school on the basis of one’s committe’s network. Without this it’s extremely hard to make a big splash. It’s almost a necessary condition.

Anyway, the frustration at the job market stems precisely from the fact that many people get given these fantastic opportunities, perform less well than those with worse jobs (higher teaching load, less reputation halo to help with publishing, etc.), and still end up better off, i.e. with tenure at better institutions.

“The frustration at the job market stems precisely from the fact that many people get given these fantastic opportunities, perform less well than those with worse jobs (higher teaching load, less reputation halo to help with publishing, etc.), and still end up better off, i.e. with tenure at better institutions.”

Sorry, no. My frustration with the job market – and that of many candidates – stems from the fact that there are not enough (decent, non-exploitative) jobs. This results in a number of pathologies that create needless work and anxiety for job applicants, placement directors, and search committees. We have to spend more time ‘sell ourselves’ and less time doing real philosophy. Candidates must apply to all jobs, because they cannot reasonably determine in advance that they have a good chance of getting any particular kind of job. Graduate education, and the business of reviewing and publishing articles, must adjust itself to the market needs of graduate students, rather than focusing on what best promotes philosophical learning and the dissemination of information.

From this perspective, the small number of people who may get better and worse (tenure-track, non-exploitative) jobs than you think they deserve is just a side-show. Under present conditions, the guaranteed outcome of the job market is that a large percentage of candidates won’t get the job they deserve, no matter how the current pool of open positions is distributed. Indeed, a large percentage will continue to get jobs that are worse than any professional educator deserves.