Political Philosophy’s “Fantasy World”

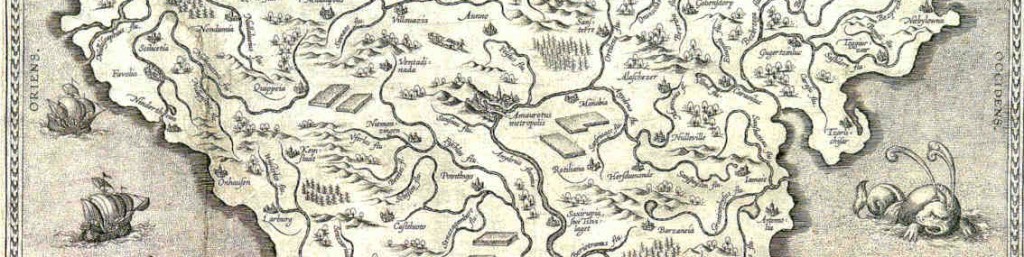

[M]ainstream political philosophy is seen as irrelevant… because of the bizarre way it has developed since Rawls (a bizarreness not recognized as such by its practitioners because of the aforementioned norms of disciplinary socialization). Social justice theory should be reconnected with its real-world roots, the correction of injustices, which means that rectificatory justice in non-ideal societies should be the theoretical priority, not distributive justice in ideal societies. Political philosophy needs to exit Rawlsland — a fantasy world in the same extraterrestrial league as Wonderland, Oz and Middle-earth (if not as much fun) — and return to planet Earth.

That’s Charles Mills, the John Evans Professor of Moral and Intellectual Philosophy at Northwestern University, in an interview with George Yancy in “The Stone” in The New York Times. Mills and Yancy discuss assorted issues in political philosophy, including idealization and racism in political philosophy’s past and present. An excerpt:

George Yancy: So, would it be fair to say that contemporary political philosophy, as engaged by many white philosophers, is a species of white racism?

Charles Mills.: That would be too strong, though I certainly wouldn’t want to discount the ongoing influence of personal racism (now more likely to be culturalist than biological — that’s another aspect of the postwar shift), especially given the alarming recent findings of cognitive psychology about the pervasiveness of implicit bias. But racialized causality can work more indirectly and structurally. You have a historically white discipline — in the United States, about 97 percent white demographically (and it’s worse in Europe), with no or hardly any people of color to raise awkward questions; you have a disciplinary bent towards abstraction, which in conjunction with the unrepresentative demographic base facilitates idealizing abstractions that abstract away from racial and other subordinations (this is Onora O’Neill’s insight from many years ago); you have a Western social justice tradition that for more than 90 percent of its history has excluded the majority of the population from equal consideration (see my former colleague Samuel Fleischacker’s A Short History of Distributive Justice, which demonstrates how recent the concept actually is); and of course you have norms of professional socialization that school the aspirant philosopher in what is supposed to be the appropriate way of approaching political philosophy, which over the past 40 years has been overwhelmingly shaped by Rawlsian “ideal theory,” the theory of a perfectly just society.

Rawls himself said in the opening pages of A Theory of Justice that we had to start with ideal theory because it was necessary for properly doing the really important thing: non-ideal theory, including the “pressing and urgent matter” of remedying injustice. But what was originally supposed to have been merely a tool has become an end in itself; the presumed antechamber to the real hall of debate is now its main site. Effectively, then, within the geography of the normative, ideal theory functions as a form of white flight. You don’t want to deal with the problems of race and the legacy of white supremacy, so, metaphorically, within the discourse of justice, you retreat from any spaces worryingly close to the inner cities and move instead to the safe and comfortable white spaces, the gated moral communities, of the segregated suburbs, from which they become normatively invisible.

The rest of the interview is here.

(art: map of Utopia by Ortelius, based on Thomas More’s Utopia)

What are some of the problems that non-ideal theorists are wrestling with these days? Would anyone mind suggesting what they take to be some of the agenda-setting articles from the recent literature?

I’m a fan of Mills’ “Ideal Theory as Ideology”, but I’m not convinced that ideal theory is the main problem. I think there are two methodological debates in political philosophy, though they are often lumped together: ideal/nonideal theory (mostly a debate among Rawlsians and other liberals), and realism/moralism (a debate that is emerging at the crossroads of analytic philosophy and critical theory, from seeds planted mostly by Raymond Geuss and Bernard Williams). Crudely, the ideal theory issue is about the extent to which we take into account feasibility constraints. The realism issue is about the sources of political normativity: do we derive political norms from pre-political moral commitments (intuitions, mostly), or is there a normativity internal to politics, with its own set of values and tied to an empirically-informed understanding of our political practices (think Machiavelli, Hume and Aristotle on some readings, Weber, etc.)? So in principle it’s possible to have ideal realist theory, nonideal moralist theory, etc.

The problems flagged by Mills seem to me more to do with moralism than with ideal theory. Reliance on moral commitments that are supposed to be justificatorily prior to normative political judgments tends to build ideological prejudices into supposedly impartial principles of justice. Okin’s feminist critique of Rawls can be read in this way, for instance. Even if we turn to nonideal theory these prejudices won’t go away if our method is moralistic, or “ethics-first”. As Geuss pithily puts it, paraphrasing Nietzsche: “Ethics is usually dead politics; the hand of a victor in some past conflict reaching out to try to extend its grip to the present and the future.”

I can’t speak for other people but my interests currently are in regards to consent and participation. Specifically, what is required for consent and how that is relevant for (a) determining whether some social identity groups are being excluded from fairly participating in governance and (b) thinking about what interventions might be employed to address the exclusion of some social identity groups from participating in governance.

P.S. My last comment was in response to Eugene’s question.

“Rawls himself said in the opening pages of A Theory of Justice that we had to start with ideal theory because it was necessary for properly doing the really important thing: non-ideal theory, including the ‘pressing and urgent matter’ of remedying injustice. But what was originally supposed to have been merely a tool has become an end in itself; the presumed antechamber to the real hall of debate is now its main site.”

I am not sure I agree with all of this critique. It is true that the past 40 or so years of political philosophy in the English-speaking world have been dominated by Rawls and refinements to various idealized projects in political philosophy. But this period has also seen the largest growth in applied philosophy, for example, in bio-medical ethics, business ethics, and normative analyses of social issues, public policy, and law, including issues of race, racism, as well as personal and institutional responses to racism, as well as transitional justice more generally. The real world has not been ignored. A lot of this work is done by philosophers who have taken the time to engage with practitioners or take up the relevant social science, and tries to be, in some sense, “practicable.” It is thus “non-ideal” in at least one sense that seems important to Mills.

That said, there is certainly room for more such work, and more work specifically on issues related to race. Additionally, there is no doubt a longstanding hierarchy in the field according to which more abstract moral and political philosophy is thought of as more prestigious, or challenging, or philosophically interesting, than applied work. My sense, though is that this has been eroding for quite some time, too, and that most people who work in these fields today consider the best applied work to be no less philosophically interesting than the best “ideal theory” work. (I think an interesting sociological and economic story can be told about the emergence of this hierarchy, but that is for another time.) Finally, there are questions about who is doing this philosophy, and the philosophical significance of the epistemic limitations of the field, given its lack of diversity.

Ideal theory was not invented by Rawls – it goes back to the very beginning of Western philosophy. My views about this are kind of unconventional but they include the judgment that ideal theory is really very important (I won’t go into it here, but see this for example.) So, unlike Mills, I am happy to see political and moral philosophers engage in ideal theory. But I think Mills is partly right. There are diminishing marginal returns in ironing out every tiny wrinkle in ideal theories and we ought not to whitewash the history of philosophy, nor ignore how the limit on perspectives has shaped the discipline, nor neglect the questions of “actual social justice.”

It’s difficult to get a good sense of Mills’s objections from this interview alone. Here are a few articles by Mills in which he develops his objections more fully:

“‘Ideal Theory’ as Ideology” (Hypatia 2005)

“Rawls on Race/Race in Rawls” (Southern J of Phil 2009)

“Retrieving Rawls for Racial Justice? Critique of Tommie Shelby” (Critical Phil of Race 2013)

I also recommend looking at some of Tommie Shelby’s work defending Rawls against Mills:

“Race and Social Justice: Rawlsian Considerations” (Fordham Law Review 2004)

“Racial Realities and Corrective Justice: A Reply to Charles Mills” (Critical Phil of Race 2013)

REPLY FROM CHARLES MILLS: Thanks to everybody for the comments.

As Walter points out, one is constrained by the limited space and restricted format of an interview. Thanks to him for the references. I would add, if anybody is interested in further sources, chapters 3 and 4 of my 2007 book with Carole Pateman, CONTRACT AND DOMINATION, where I attempt to modify Rawls’s contract for non-ideal theory (arguing for reparations for black Americans) and an essay published this year, “White Time: The Chronic Injustice of Ideal Theory,” where I suggest that “ideal theory” as it has come to be developed by the white political philosophy community is underpinned by a racialized temporality, and that this is in keeping with the long 2500-year history of a Western social justice tradition exclusionary of the majority of the population for more than 90 percent of its existence. (See Fleischacker’s book for documentation.) “White Time” can be found in a special issue of the Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race (Vol. 11, no. 1, Spring 2014), co-edited by Robert Gooding-Williams and myself on the theme of “Race in a ‘Postracial’ Epoch.”

Justin: Yes, you’re right of course that applied ethics has expanded considerably, but I do think (as you mention) that such work is seen as low-prestige in the profession, as compared with the putatively more demanding theorization of social justice. You suggest that this is changing–well, maybe. But even if it is, I still think one can legitimately ask why what is supposed to be the go-to location for normative debate about the “basic structure” of society ignores race and racial justice so thoroughly, especially in a society like our own to whose history and structure racial injustice has been so central.

Enzo: Glad to hear you like the “‘Ideal Theory’ as Ideology” essay. You’re certainly correct that these contrasts (ideal/non-ideal) are ambiguous, subsuming more than one set of debates and contrasting theoretical positions. An ironic manifestation of this is that neither of the two debates/contrasts you cite is the one I actually had in mind. The kind of “non-ideal” theory I meant was what Rawls refers to on p. 8 of the book (1999 edition) as “compensatory justice,” which I am reading as the same thing as Nozick’s “rectification of injustice in holdings” (ASU, pp. 152-53) and Aristotle’s “rectificatory justice.” The very fact that this sense of non-ideal theory is so absent from the recent debates about non-ideal theory vindicates my point, I would claim. My contention is that structural reform to achieve rectificatory racial justice in the United States (and elsewhere) for people of color is crucial, and that the non-discussion of these issues in the justice literature testifies to a “whiteness” not merely demographic but conceptual and theoretical. That’s one of the basic points I was trying to gt across in the interview.

Hope that helps to clarify things.