Challenges Facing Philosophy of Science

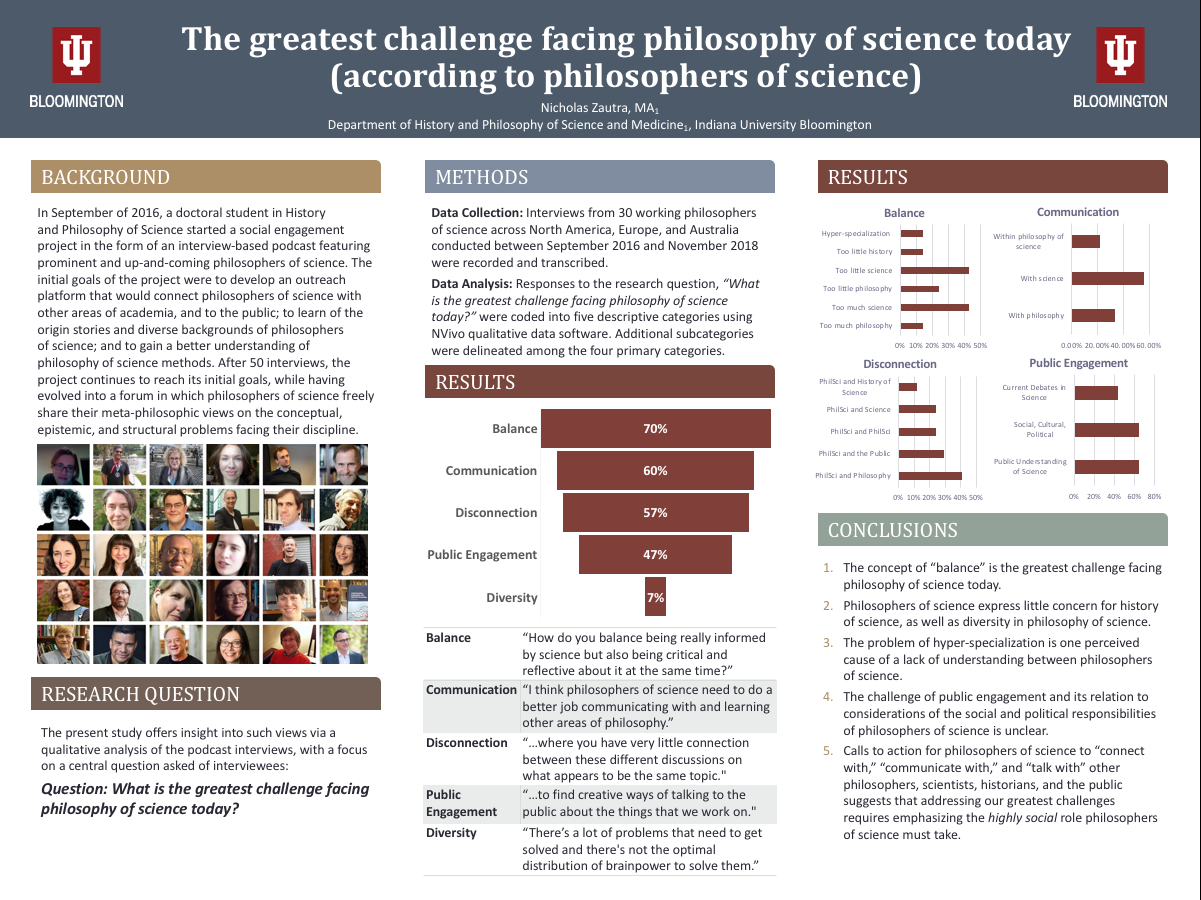

What are the most significant challenges facing philosophy of science today? Nick Zautra, a PhD student in the history and philosophy of science at Indiana University Bloomington, interviewed 30 philosophers of science over the past two years, asking them this question, and presented a summary of their answers at the recent 2018 Philosophy of Science Association (PSA) meeting.

Zautra, who hosts the Sci Phi Podcast (previously), found that the most common answer to the question were about “balance,” that is the challenge of “being really informed by science but also being critical and reflective about it at the same time.” Over 40% of the answers categorized into this group expressed a concern about philosophy of science involving “too little science.” Roughly the same proportion of answers expressed a concern about philosophy of science involving “too much science”. The third most prominent concern expressed was “too little philosophy.”

Besides “balance,” other challenges to philosophy of science noted by his interviewees included improving communication with other areas of philosophy, addressing the apparent “disconnection” between different discussions of the same topic, finding better ways to engage with the public, and improving diversity in the field.

Here is an image of the poster Zautra designed to share the results of his survey at the PSA meeting:

I asked Zautra what philosophers who are not working in philosophy of science should take from his findings. He replied:

I think what is most important for philosophers in other subfields to know is that philosophers of science are concerned about the disconnection between more traditional metaphysics and epistemology, on the one hand, and on the other, philosophy of science. Misunderstanding and miscommunication between, for example, metaphysics and philosophy of physics, and epistemology and philosophy of cognitive science is seen as a real problem. Philosophical work across the board is perceived to be weakened as a result. Philosophers of science would like to see relationships between more traditional M&E philosophy and philosophy of science improved (so much so that they’re writing papers about it). I think meeting this challenge begins with philosophers of science recognizing their highly social role as cross-disciplinary researchers. Not only must they communicate and engage with the scientists, but they must also work closely with their more traditional M&E colleagues who could help them to better make sense of and/or point them to relevant literature concerning the philosophical implications of their work. In turn, it would be fantastic if traditional M&E folks would be open to finding common ground on philosophical problems of which philosophers of science may contribute.

He added that concerns similar to those had by philosophers of science might arise for philosophers in other areas:

It’s difficult to say without speaking directly to philosophers in other subfields how generalizable the perceived challenges in philosophy of science are to other areas in philosophy. But I think the results from this study might be a good starting template to begin thinking about what more traditional M&E philosophers might consider to be their greatest challenges. Is there an issue with “balance” in Ethics? Are there communication problems between philosophers of mind and epistemologists? Is their a problem of “hyper-specialization” in philosophy? Does philosophy lack a sense of unity? Do philosophers across disciplines, and even in the same discipline seem to be talking past one another? Do philosophers consider diversity an epistemic issue? How should philosophers engage with the public?

Thoughts from philosophers—in philosophy of science or not—and scientists welcome.

I’m not at all sure that “balance” is what should be sought, or even whether it is possible. I don’t expect scientists to be experts in philosophy nor philosophers to know the ins and outs of the latest science research. In my own work on Time as a philosopher, as described in my just-published book, I show that even though philosophy can run parallel with science by coming to similar conclusions but from a different angle, it is not the philosopher’s function to “back up” scientific findings. Philosophy stands on its own as a discipline while being part of a commonality of knowledge.

Ronald Green

“Time To Tell: a look at how we tick” (iff Books, 2018)

From Zautra’s reply:

“meeting this challenge begins with philosophers of science recognizing their highly social role as cross-disciplinary researchers. Not only must they communicate and engage with the scientists, but they must also work closely with their more traditional M&E colleagues who could help them to better make sense of and/or point them to relevant literature concerning the philosophical implications of their work.”

As collective advice to the discipline, this sounds sensible, but not necessarily as advice to individual researchers. One goal of philosophy of science is to connect to, inform, and be informed by, metaphysics. But another is to contribute to the progress of a given scientific field by helping with its conceptual issues. For the latter, I’m not at all convinced that the marginal benefit from engaging more deeply in M&E exceeds the marginal benefit from spending more time learning the science.

For background, I a STEM field academic with an interest and appreciation for philosophy. I appreciate the intellectual rigor with which the field of academic philosophy is practiced, and I want to be clear up front that my comments are presented as a sincere criticism made from a person who respects the field and understands I am not an expert in it, so I accept I may have an incomplete or inaccurate perspective.

That said, these are my observations about the philosophy of science from the perspective of a scientist. Valid philosophical academic work needs to be made by philosophers who have a scientifically expert understanding of the subject they are writing about. I have trouble taking philosophical musings about the nature of time seriously from anyone who doesn’t thoroughly understand a Lorentz transformation. I cannot see how someone without a firm grasp of the latest neuroscientific research on perception has a lot to offer in conceptual elucidation of the subject. Philosophers with a very poor grasp of scientific findings are responsible for a lot of very widespread public misunderstandings about scientific discoveries and it can be very frustrating for scientists. (And to be fair, journalists are responsible for far more nonsense than philosophers.)

I realize that maintaining that level of expertise in two somewhat disparate fields is a lot to ask, but understanding tensor calculus is not incidental to general relativity and its fundamental philosophical underpinnings. This dearth of a true understanding of the science applies to much of what I read in the philosophy of science. As I stated initially, I’m open to the possibility that I’m mistaken, but I see a lot of woo coming out of this field.

I would like to share an amusing comment on the topic made by a colleague over lunch.

“It is an unfortunate situation in which we have philosophers publishing bad science and scientists producing bad philosophy.”

I understand your point. But if you require philosophers to have an “scientifically expert understanding” of science, then surely we need to expect scientists to be as such when they refer to philosophy, especially when they do so disparagingly not knowing the basics of philosophical thought. The point, though, is that they are separate disciplines, albeit part of a unity of knowledge yet different prisms of that knowledge.

You are right that philosophers should not discuss matters that they don’t know about. The problem is, as you stated in a later post, when we have a “situation in which we have philosophers publishing bad science and scientists producing bad philosophy.” But philosophy and science, being disparate disciplines, should be looking at what they know. So when it comes to Time, physicists examine what Time *is*, whereas philosophers are concerned with what Time *does*.

We need to stop the woo on both sides.

Let me start by saying that I did not initially notice that you are the author of a philosophy piece on the subject of time. I am not familiar with either you or your work and I apologize if it seemed my comment about time in the initial post was an oblique jab at you. It definitely was not.

Regarding your comment, it does not seem fair to compare a request for rigor and understanding in an academic publication to a comment on a blog. I am trying to have a polite conversation, whereas an academic publication has somewhat more lofty goals (one hopes). Further, I took several philosophy courses as an undergrad and feel I have a pretty good grasp of the basics of philosophical thought, and I am confident most philosophers of science have a good grasp on the basics of the science they are writing about.

Believe it or not, mathmateical equations actually do describe what time does, as well as what it is. There are a number of ways to interpret the scientific understanding of these equations if one understands the maths, and theoretical physics is in desperate need of new thought right now. If one is truly attempting to add to the depth and breadth of human knowledge in a substantive and meaningful manner (as opposed to writing for entertainment, financial gain, add to CV, ect.), then it isn’t clear to me how someone can accomplish that without truly understanding the science.

I don’t think the situations are symmetric. It’s true that physicists in particular often say very silly things about philosophy in popular and semi-popular writings. But I have come across extremely few cases (there are a few) where physicists in the peer-reviewed physics literature say something that makes an improper or false assumption about some piece of philosophy knowledge.* I have come across a great many cases in the peer-reviewed philosophy literature where there is consequential error or ignorance about a matter of physics knowledge.

* Distinguish this from the claim that conceptual clarity is sometimes lacking in the physics literature, and that literature would benefit from the application of philosophical methods. (I have some time for that view, though it can be overstated.)

Honestly, looking from outside the academic world, and thinking about entering it, this whole conversation is very concerning to me. Instead of working together, of learning everything that you can on said subject (from every perspective! What would the ancient philosophers would say about studying only one small angle of the world!), every researcher stays in his own field, always thinking that it has supremacy (yes, physics doesn’t “own” time, neither does mathematics or philosophy, that’s why it was called philosophy of nature, that encompassed it all, or have you all forgotten your roots?). This truly saddens me.

Consider the question of whether modern physics implies that the “moving now” along the time dimension (our experience of change) is an “illusion,” as suggested by some physicists and at least accepted by some philosophers and rejected by others. This seems to me to be a very hard question partly because answering it requires both an expert understanding of the relevant theories from physics and a substantial understanding of if, when, and how a scientific theory could have that kind of metaphysical implications in the first place. It’s not obvious that a single individual can possess the required understanding from both fields. Rather than making somewhat unrealistic demands of individual scientists and philosophers, maybe what we need is more cooperation. (I think there is more of that in the philosophy of science already, than in other areas of philosophy, but I may be wrong.)

“Philosophers with a very poor grasp of scientific findings are responsible for a lot of very widespread public misunderstandings about scientific discoveries…”

I very much doubt that.

Babette Babich’s take:

https://www.academia.edu/34857869/Hermeneutics_and_its_Discontents_in_Philosophy_of_Science_On_Bruno_Latour_the_Science_Wars_Mockery_and_Immortal_Models

Seems to me that if one is attempting to say something significant about philosophy of x, then one should know everything that one could about x. Meta-knowledge can’t claim anything like authority unless one knows what one is talking about. I studied for many years to say anything of merit about special relativity with respect to the philosophy of time (and only modestly contributed), but I would be a dolt to try and contribute to literature about (e.g.) relativistic quantum mechanics. One should be at least competent–and better, master–any x to philosophize about x in a helpful way.

Given my own experience, I would add that it’s quite unlikely that philosophers of science can get by with merely consulting scientists. The problem is that scientists generally don’t know and don’t care about the minutia that matters to philosophers, precisely because none of it makes an empirical difference. Physicists will typically just tell you that totally distinct mathematical frameworks are the same because they don’t make an empirical difference, even if they’re naturally interpreted as presupposing entirely different ontologies. For that matter, they’ll typically deny that quantum physics has an ontology (or say something downright inconsistent or otherwise crazy). Try asking a physicist if they can get by with only constructive mathematics and they probably won’t have the foggiest idea what you’re talking about. Clarify and they’ll look at you like you’re a crazy idiot for being skeptical of indirect proof. They generally won’t be aware of alternative frameworks if they aren’t convenient to use and will probably tell you that there is only one way to approach a problem simply because it was the way they were taught. In fact, communication with physicists can be misleading and counterproductive because both parties are likely to be unaware of the fact they are talking at cross purposes. Sometimes in the midst of these conversations I am made to wonder if one of us is actually Wittgenstein’s lion.

I think you *can* consult, but you need a reasonably strong grounding in the science yourself in order to speak the language, and you need to recognize that the questions you’re interested in overlap but aren’t identical to the questions the scientist is interested in.

Case in point: you say, “[p]hysicists will typically just tell you that totally distinct mathematical frameworks are the same because they don’t make an empirical difference, even if they’re naturally interpreted as presupposing entirely different ontologies.” Here, “empirically equivalent” means something finer-grained than van Fraasen’s notion; it’s something like “there’s a systematic content-preserving translation manual between these mathematical frameworks, in a way that leaves in-principle-empirically-relevant content unchanged”. So then you can either (a) dispute that it’s actually true that the two mathematical frameworks are intertranslatable, (b) take the existence of that intertranslatability as evidence that we need a coarser-grained metaphysics (that’s how I think about French/Ladyman/Ross-style ontic structural realism), or (c) recognize that science (and not just empirical data) underdetermines metaphysics, in which case of course scientists aren’t going to have any further contribution to make as to which ontology is right.

In my experience physicists mean something far less sophisticated, to the effect of “you can use either framework to solve problems and they will both get you the right results in experiments once you account for the various ways in which they idealize things”. I think the more basic problem is that you can’t really ask them the right sorts of questions because they don’t think of the theories as formal languages that imply things. When you talk to them of what the theory implies they usually take you to be asking about what experiments you can construct to test it. For instance, they’re pretty callous and handwavy about infinity and renormalization. They wouldn’t care if you can come up with a framework in which you don’t get infinite physical magnitudes unless it also happens to be more convenient to work with (which it probably won’t be). You just ignore infinities when they come up. Then again, I really only know experimentalists. Theoreticians might be more sensitive to these things.

Very valuable article!

Lee Smolin in “The Trouble With Physics: The Rise of String Theory, The Fall of a Science, and

What Comes Next” well presented the situation in fundamental physics, and Morris Kline in “Mathematics. Loss of Certainty” – in mathematics.

№1 problem for philosophy and science – the ontological justification (basification) of mathematics (knowledge). But mathematicians and physicists sweep this age-old problem under the carpet. Here new ontological ideas are needed to understand matter, space, time, information, consciousness.

Just look at the philosophical themes of the FQXi’s contests for the years 2008-2017

https://fqxi.org/community/essay/closed

There are two good covenant physicist and philosopher:

“Philosophy is too important to be left to the philosophers.” (John Archibald Wheeler)

“An educated people without a metaphysics is like a richly decorated temple without a holy of holies.” (G.Hegel)

Conclusion: physicists and philosophers must work together to overcome the crisis of understanding in the foundations of knowledge.

I also like

“No science can safely be abandoned entirely to its own devotees.”–John Venn

I’m also from the science rather than philosophy side of things. As others have said, I think the best place for mutual interactions is in philosophy of/in science X, where the contribution from philosophy can be on multiple fronts. Consider epidemiology, where there is much interest in causation, inference and bias in thinking.

A) Look at Table 1 of

https://jech.bmj.com/content/jech/58/8/635.full.pdf

(some of this may appear in informal logic survey subjects)

B) See the contributions of Clark Glymour and collaborators in

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.134.1601&rep=rep1&type=pdf

(it is possible that some might argue this has already strayed too far from philosophy qua philosophy, but there are many issues of relevance)

C) Look at the genetic correlation in Figure 6 of

https://www.biorxiv.org/content/biorxiv/early/2018/10/30/457515.full.pdf

where we see, for example, a (negative) genetic correlation of -0.7 between IQ and supporting the Labour Party, as well as being born in the coal mining areas.

To sensibly interpret the latter in terms of causation (especially if one is looking at results from mendelian randomization), one needs a certain amount of statistics and genetics knowledge, but the issues are to some extent philosophical in nature – are genes causes, how does one interpret genetic differences and variances, are historical population movements causes. They do not need knee-jerk responses about social construction of IQ tests and so forth.

That was my point: that the sides are not symmetric. To imply that this is a good situation is problematic on its own, and it is endemic in a world in which the humanities are looked down upon as somehow inferior to science. It is the culture of “shut up, and calculate.” Typical of this attitude is that of John Archibald Wheeler quoted above: “Philosophy is too important to be left to the philosophers.” What would scientists say to an eminent philosopher saying, “Science is too important to be left to the scientists.”? Unimaginable, isn’t it? Why? Because scientists have more to say about how the world “really” is?

Scientists have no more idea about “the underlying nature of reality” than philosophers do, even though our materialistic world believes that only science can tell us what is really important. This is being reinforced by scientists, who really believe – and say – that philosophy has nothing further to add, and that calculations and measurements say it all. Theirs is world that have nothing to say about morality, ethics, feelings, etc. In short a world bereft of humans. At the least they are dismissive of philosophy itself in case it disturbs calculations. So we have Lawrence Krauss, who, when positing a universe that arose from nothing, stating that he doesn’t mean “nothing that philosophers mean.” As a demeaning remark it doesn’t mean much. But his theory stands or falls on what “nothing” is (or isn’t). If nothing is something, a universe simply does not come from nothing. Krauss dismisses philosophy at his peril.

Unless we make science and philosophy symmetric and realize that both are equally important in an ever more chaotic world, where science is becoming politicized because there are no checks and balances from “thinkers”, we are on a difficult path. We may as well relax, watch reality shows and perhaps even vote in politicians who perform best.

I agree whole heartedly with Vladimir Rogozhin’s last paragraph.

As in other fields of thought, the greatest challenge nowadays, is to realize how important moods are for all and any inquiry. Moods truly direct inquiry, and what is viewed as valid fields of studies or significant objections.

‘Moods’ or methods?

As someone with their foot in both camps but seemingly more in the science camp, my impression is that scientists will often take mistakes about the details as reasons to object to the wider picture when it is very clearly irrelevant to the point. While philosophers should aim for accuracy, their claims rarely hinge on a single empirical fact. Scientists who are looking for a reason to confirm their doubts about philosophers will latch on to something as minor as a phrasing they’re uncomfortable with.

On the other hand, while I occasionally encounter work that I consider inefficient in philosophy of science due to either lack of domain knowledge or technical skill (I was able to code up a model that someone at the PSA was getting at within the space of their talk whereas they saw it as a stretch goal). Rarely do I encounter work that is scientifically flawed.