Why To Discourage Laptops in Class (with slides you can show your students)

You may have seen various articles about how computers and phones in the classroom affect student performance.

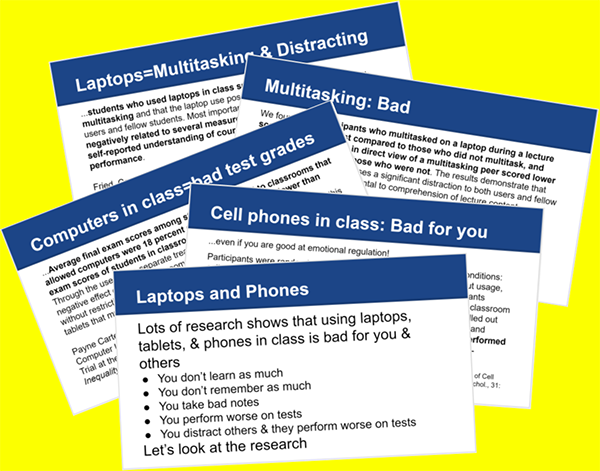

Andrew Mills, professor of philosophy at Otterbein University, summarizes this research for his students, and has generously made his slides on the subject available for other professors to use in their courses.

The slides are well-organized and taken together form a general argument against students using electronic devices in the classroom. (Of course, it may be the case that for certain individuals or in certain circumstances, the balance of reasons favors their use.)

None of the slides explicitly calls for a ban of such technology or any specific classroom technology policy; it leaves it up to professors to craft specific technology policies for their courses, or perhaps to just present the slides and let their students choose how to make use of the information therein.

You can view the slides here.

This is commented upon in the original post above, but I wanted to take a moment to stress this crucial distinction.

All of these studies operate on what is true “on average.” In any particular case, a laptop may be much more helpful for the student. For instance, take the claim that “students who took notes on laptops performed worse on conceptual questions than students who took notes longhand.” I don’t disbelieve that, but it’s very difficult for me to read my own handwriting, so notes I take longhand are pretty useless.

Isn’t the best option to leave it up to the students how to shape their learning, while providing them with this information to consider? My suspicion is that professors ban laptops mainly because they want their students to look at them more, rather than because the scientific data has solidified their intention to ban the use of laptops for every student without medical justification. I’ve had several classes where professors ban technology, citing one of these studies, totally blind to the fact that studies operate on aggregate averages rather than particular learning outcomes.

You say “professors ban laptops mainly because they want their students to look at them more” as if that’s a bad thing.

Joking aside: Having laptops and other electronic devices being used in the room pollutes the space for those not using them. You’ve got to accommodate the students who have legitimate reasons to use them, of course, but if you don’t try to keep the space as clean as possible by preventing all the students who don’t have such legitimate reasons from using their electronic devices in class, you are by neglect harming students in the class who would benefit from having an electronic-device-free space.

Also, it’s possible and perhaps even likely that there are students in the class who have gotten themselves into habits where they struggle to learn without using their electronic devices but who would benefit if given the incentive and opportunity to break those habits. The mere fact, if it is a fact, that some students find themselves in situations where they struggle to learn as well in class without their devices as they do with their devices does not in itself show that there is not an obligation that teachers have to try to keep the classroom space as device-free as possible.

I don’t ban laptops because I want my students to look at me more. I ban them because I want them to look at each other more.

And listen to each other more.

I will say one of my pet peeves as an undergrad were the professors who would go into long diatribes about how the best way of learning the material was X, with X usually some fairly ridiculous and convoluted process (frequently “take copious notes, then go home and rewrite those notes by hand”). Some people learn in different ways. And certainly I type about 4 times as fast as I handwrite, so laptops were far easier for me (though I barely took notes at all and learned better by just listening).

funny thing is that that is exactly what the vast majority of my A+ level students report doing: taking copious notes, rewriting their notes, reviewing their notes…

I thought I’d mention here that one explanation for why taking notes by hand helps with conceptual questions, etc. – and is more generally better than taking notes on a computer – has nothing to do with being able to ever look at those notes again.

The process of writing by hand is slower and more deliberate, and that in itself helps with the initial learning. So even if one were to write notes that were unreadable at a later date, you may still be better off than typing notes that can be read later on. It will turn on how valuable the later review really is relative to the first engagement.

There’s something to be said for the claim that the negative effects of laptop use being averages, with some individual students not (as) affected as the data would suggest. For example, as suggested above by GradStudent4, students with atrocious handwriting might benefit from digital notes in a way that the “average” student might not.

The usual response, also suggested above by sg, is to note the increasingly large body of research indicating that one student’s laptop use has a particularly deleterious effect on students around the laptop user, even if (especially if, according to some research) they themselves are not on laptops and that average effects are meaningful reasons for a ban.

What I find increasingly interesting about these debates is that most of the consideration tends to be given to typical students, rather than students who are entitled to accommodations under the ADA. Mills’ slides do a great job, for example, of laying out the research as a means of arguing against laptop use by a typical student. sg, above, notes that we have to accommodate legitimate laptop accommodations but quickly moves on to the larger point. (No knock on sg, BTW. It’s a comment on a blog and not a 7,000 word essay.) I move on from ADA concerns, in retrospect, more quickly than I would have liked to in work I’ve done on the topic.

I guess what troubles me is this. I worry that we’re not paying enough attention to the effects laptop bans have not on the occasional student who happens to fall outside of the mean, but on students who have legitimate disability-related reasons to have laptop access. I think my question can be asked in one of two ways: First, are laptop bans prima facie ableist? Second, what pedagogical design principles can we employ to avoid the negative effects of a laptop ban on disabled students if we were to ban laptops?

I type up notes myself for students with ADA documentation.

1. Yes, I think they are.

2. Having a ban with exemptions for disability isn’t enough (this forces anyone making use of the exemption to broadcast private information about themselves to the entire lecture hall).

3. I think that if an instructor really wants to give students an anti-laptop spiel (I don’t do this myself), the instructor should do something like present their reasons for thinking that most students shouldn’t use laptops, then discuss multiple reasons that a student might elect to use a laptop, despite this trend, and then allow students to use a laptop without explaining why they are doing so. This prevents students from making conclusions about disability just on the basis of observing some laptop use.

Students with diagnosed need for laptops get exemptions.

Thus singling them out for the whole class. This is problematic, at least to me.

What is going on in the classrooms? Why are students taking notes? There are books for them to read, they can take notes on those. If you are lecturing you can type out what you are saying, and the students can read it. Of course, students need to have a piece of paper, and a pen, to write stuff down, so they can organize their thoughts, and the thoughts of their fellow students. But that’s for what’s going on in the moment, not posterity.

If a student with a learning disability does need typed notes, and you can’t provide them, then another student can take the notes on a laptop. This is pretty standard here, so a student with a disability who, in fact, is given permission to use a laptop is not identified as having a disability but as taking notes for someone who has a disability.

I think providing this information is a great idea. But it just seems odd to REQUIRE any student do what has proven best for students, on average. On average most people get more work done if they do it in the morning. Many studies show this. But many of the greatest minds have sleept in until noon and worked all night. While students with disabilities is an interesting issue, it is easy to make an argument against bans without appealing to disabilities at all. If student, “Ted”, learns better with a laptop, he should be able to use it. I don’t really get other students finding it distracting. Even if they do find it distracting, that doesn’t seem grounds to ban Ted from taking notes, in his own desk, in the way he sees fit. Students are distracted by all sorts of things, such as good looking students, certain types of clothing, certain ways of speaking, etc. But none of these things should be banned.

Would you also say that it is wrong for a teacher to tell students that they are expected to arrive to a 12:00 class on time because some of the greatest minds have slept until noon and worked all night?

Is the argument (for those who want to ban laptops, and many do) really:

-Even though some students learn better by using laptops, overall more students would benefit if laptops are banned.

-We should always do what benefits the most students, even if it hurts other students (as long as they are not disabled) who happen to have a different learning style than the majority.

-Given the above, we should ban laptops.

Does anyone want to deny the first clause of the first premise?

The ‘always’ in premise 2 makes it too strong.

On another note, while it surely is legit to talk in terms of different “learning styles,” we should be wary of treating them as rigid, unchanging patterns that an individual is stuck with for a lifetime. In many cases what are called “learning styles” are mere habits, and creating learning spaces where habits are changed and people are transformed is as much a part of our work as teachers as is “transmitting content.” It’s hard to get that right, of course, but that’s why teachers make the big bucks.

I think a more charitable rendition of the argument would be:

1. Even though some students learn better by using laptops (including some who will not be able to give a good argument for that conclusion), overall more students would benefit if there was a general rule against laptop use, with exceptions in cases where students have a good argument for why they need one.

2. We should adopt rules in the classroom that have the best consequences, as long as we don’t violate any moral (or legal or contractual, I guess) side constraints–e.g., violate a student’s rights.

3. Students don’t have a moral or legal or contractual right to use a laptop in the classroom, at least in cases where they can’t give a good argument for why they need one.

4. Therefore, teachers should adopt a general rule against laptop use, with exceptions in cases where students have a good argument for why they need one.

This seems like a pretty good argument to me, I confess. What premises do people deny?

I attend a college in the US and I have an ADA accommodation for keyboarding in the classroom, for which I have been shamed by a professor in front of my peers.

First, ADA letters at my college inexplicably go out the first 1-2 week after classes begin. The explanation I have been given for this is that students may not know what accommodations they will need until they find out what requirements the course has. For some reason, they insist on making the letter as narrow as possible, so that if a particular accommodation doesn’t apply to a particular course that accommodation won’t be listed for that professor. This creates a terrible backlog where the letters are almost always late beyond the 1-2 weeks.

So, this means any accommodations used in the first couple of weeks of class have to be negotiated with the professor, with a promise that a letter is coming. The first week of class, actually the first lecture of class, however, is when the professor (and only young ones—never old professors) go over the information ad nauseam about how laptops are distracting.

In one course, the professor showed a video from some news organization on how laptops not only hurt an individual student’s performance but they also negatively impacted everyone around them—bringing down grades for everyone in the class.

Slowly, the sea of laptops were put away one by one, until there was only me sitting left—the single student with a laptop on his desk—looking like a complete misanthrope who wanted to throw down the GPA of the entire class over my refusal to put my computer away.

Was I supposed to at that point make a ground announcement of why I had my computer sitting out? I already have Tourette’s to contend with and have to worry about affecting others.

I now drop classes if I get a syllabus and see ridiculous pedanticism.

One professor had a quote from Hobbes next to her laptop policy:

“To hearken to a mans counsell, or discourse of what kind soever, is to Honour; as a signe we think him wise, or eloquent, or witty. To sleep, or go forth, or talk the while is to Dishonour.”

With Tourette’s and a note in my letter that I may step out of class from time to time, that was a minefield I chose not to enter.

As I said, I have only recently come across this problem, and it is only with younger “hotshot” professors.

Older professors tend to be nice, flexible, not hung up on the form but rather the content and effort, and have never hassled me about an accommodation.

I know this because I am a non-traditional student who started college in 2001, left on medical leave, and did not return until a couple of years ago, when this anti-laptop trend seemingly began. And there were plenty of students with laptops in 2001, too. All this hand-wringing about technology is a bit amnesic.

What happened to you in that one class sucks, and, with regard to accommodating students who are entitled to modifications of class during the first weeks of a semester when everything is a bureaucratic nightmare, I can’t imagine giving a student any grief if they communicate to me that they have a right to use a keyboard in class.

What happened to you in that one course seems to show that giving an “anti-laptop talk” in class in order to try to encourage students who don’t need their electronic devices in class to put them away is not the best policy.

Something like what Sophie Horowitz describes below (i.e., “to ban laptops, but then allow students to request an exception, whether it be for disability status or any other reason, including bad handwriting, etc.”) seems like a much better policy.

What I have done lately is to let students know that in general electronic devices are not allowed in class but that there important exceptions to that rule that include, of course, situations in which a student has official accommodations, but also include cases in which a student comes to me and makes a good argument for why they should be permitted to use such-and-such a device in class. If a student uses a device in class and it’s obvious to the other students that I notice it and do not object, the other students have no way of knowing whether the student is doing it because of some official ADA-related accommodation or because the student with the device came to me and made a good argument.

Your proposal would single-out and make visible all and only those students whose disability accommodation allows for laptop use. That’s not a great policy on my end.

I tell my students that research suggests that laptops are not great for note-taking for most people but that they’re great for some people. That the purpose of college is, in part, to learn how you work best and that it’s important to try out different learning strategies (i.e. what go you through high school is probably not going to work in college so try something new!).

That being said, I tell my students that they are adults and free to make their own decisions.

How does my proposal “single-out and make visible all and only those students whose disability accommodation allows for laptop use”?

What I tried to say above was that I tell my students that there are two kinds of exception to the “no electronic devices” rule: (1) students who have official accommodations and (2) students who come to me and make good arguments for why they should be permitted to use such-and-such a device in class.

I not-infrequently have students who do not have official accommodations communicate with me and ask to use a electronic device in class and give me reasons why they think they should be allowed to use it. Sometimes I tell these students without official accommodations no; other times I let them use a device in class, but I get them to commit to me directly not to be texting or looking online at stuff or whatever.

The approach you are describing seems good, too–but it runs the risk of creating a situation such as the one Marcus discusses in his post above in which “the sea of laptops” gets put away and inadvertently the students with official accommodations get revealed by default.

The reasons that the students who do not have official accommodations can give me that might get them permission to use an electronic device are varied. Sometimes its something like “the Kindle version of the book is 2/3 the price of renting a used paperback copy and I am struggling to afford the books and I promise I will not use my tablet for anything other than reading the book when we go over it in class” or “my spirit animal told me that I would learn better if I used my laptop to take notes and I always listen to my spirit animal and I think you should, too” or whatever. If the reason sounds good (and both of those reasons sound damn good to me), I let them use the device in class.

“I tell my students that they are adults and free to make their own decisions.”

I teach at a public institution where the government pays a considerable fraction of my salary, so I am responsible for inducing the students to learn whether they like it or not. They are adults, and if they don’t want to learn, they shouldn’t accept state subsidies for attending college. And I shouldn’t accept a salary under false pretenses.

Younger professors aren’t trying to be “hotshots.” They are trying to get evaluations that are mostly positive. In my experience, when students use laptops they don’t really understand lectures or engage in discussions, and so start to do poorly on assignments. Then, because they feel badly about this, they start doing even worse and stop showing up. At the end of the class they have had a bad experience and blame the professor. I am all in favor of accommodations for people who need them but learning requires change, and change is hard.

This is a genuine question about the disability accommodations argument. Even if allowing laptops benefits some disabled students, doesn’t it harm others? I haven’t been teaching that long, but I’ve gotten *many* disability accommodations requests that specify a “distraction-free environment.” (I have never gotten a disability accommodations requests specifying that the student needs a laptop. The closest I have gotten is a request for a note taker, which requires me to post notes or to allow a different student to use a laptop.) Surely one’s classmates checking facebook/shopping online/texting/etc. is a distraction, and allowing laptops makes the classroom less accessible for those students. So even if I only cared about making my classroom accessible for students with disabilities, a blanket policy of allowing laptops wouldn’t necessarily be the way to go. It seems prima facie a good idea to make the default be laptop-free and allow exceptions in a low-key and reasonable way. Is there something wrong with that argument? Are there lots more students who should be getting laptops as accommodations, but are not?

(fwiw my current policy is to ban laptops, but then allow students to request an exception, whether it be for disability status or any other reason, including bad handwriting, etc. I do make them come talk to me instead of just deciding on their own, because I think the latter would result in every student using their laptop. I know that system isn’t perfect.)

I don’t have a laptop ban in my classroom, and I’d like to make a general note about some commenters who do have a ban, who have posted in this thread.

Some of you have said that you make exemptions for students who come and make a good case to you about their laptop use. If you’re one of those instructors, I urge you to take another look at the comment by Marcus above, in particular ” … that was a minefield I chose not to enter”. It is not hard to find many more stories like this online if you do a bit of looking.

It takes a lot of work to signal to students that you’re a person worth trying to engage in this sort of conversation, and starting off the class with this anti-laptop slideshow (e.g.) signals the opposite.

Point well taken about it taking a lot of work to signal that stuff to students in the right way. And what Marcus describes above includes what sound like some bad calls on the part of faculty Marcus encountered.

But it is important to note that overall situation Marcus describes above is one in which there are already ADA accommodations in place. I don’t want to speak to Marcus’ case directly, since I don’t know the details of how things were handled at that institution, but for students who have such official accommodations, a simple “I have official accommodations that allow me to use such-and-such and the university is delayed at the start of the semester in terms of sending out the notices about my accommodations to faculty, but those notices are coming and I need to be able to utilize those accommodations in the meantime” email or verbal communication before class would seem to be all that should be needed there.

When I talk about a student needing to make a good case to me above, I am talking about students who don’t have official accommodations and are not in the process of applying for them but believe they do better in class when using their laptop or tablet or whatever and want to be allowed to use those devices.

My first year teaching I had a huge problem with students using laptops in seminars. They hid behind their screens, didn’t participate, and just furiously typed everything I said. This made classroom discussion (the point of the seminar) very difficult, if not impossible. The second year in the first class of term I explained that I strongly recommended students not use laptops and outlined the reasons. I said I wasn’t banning them, but strongly encouraging them not to use them unless necessary and that phones were not to be placed on tables/looked at during the seminar. Laptop usage went down from about 95% to 10-15% (estimates of course) and the class discussions were markedly better. I managed to realise most of the benefits of a ban without banning anything or requiring disabled students to justify their use/single themselves out.

I put this slideshow together not so much to make the argument for an outright ban, but rather to offer faculty who do want to ban (with, of course, exceptions) laptops resources to share with their students. I have found that if one does want to restrict or ban laptops, students who see the reasoning behind such a ban are more likely to accept it.

In other words, the approach with these slides is not “Here’s why you should ban laptops” but “If you do want to ban laptops, here are some studies to share with your students.”

Thank you for putting this together, Andrew! I have a laptop ban in my Intro class, and this will be extremely useful. Up to now, I just had a footnote on the syllabus with a couple references.

Have you ever been a peer observer in a class where professors allow laptops? I see 90% of laptop users watching videos without sound, while typing in a chat window, online shopping, scrolling through Instagram or Twitter. Those classes also seemed to have only a handful of people engaged with the person upfront, whether that was the professor or, in a few observations, a student presenter.

Before I started banning laptops I had numerous requests from students to ban them, for exactly this reason. I employed a student to sit at the back of a lecture class and monitor laptop use. After her report I have never had any hesitation in maintaining the ban.

Phones are worse.

Although I tell my students about these studies, I do not ban electronic devices. However, I ask anyone using them for note-taking purposes to (1) turn off their sound and internet access, and (2) to sit somewhere in the classroom which minimizes the visibility of their screens to others. That usually means the back of the classroom, though sometimes sitting in an row next to a sidewall has the same effect. This seems to me to get around all of the paternalistic concerns and the concerns about forcing students to reveal their disability or penmanship status.

I also always provide a detailed handout–really an outline–from which I lecture. This seems to me to have minimized the number of students who use electronic devices in my class since most of them just take notes of their handout. The few that do seem to be wasting their time on the internet, but I tend to be the only one who notices since they are sitting behind everyone else. If they are distracting others, I call them out and tell them to close it. If they are not, I do not say anything. I likewise do not call out people who try to surreptitiously check their phone underneath their desk, with the characteristic bizarre posture that gives it away. I instead tell them at the beginning of the term that so long as they are not distracting other students, they are free to waste their time and money not getting an education. Some still complain when they do not get good grades, but so it goes.

“they are free to waste their time and money not getting an education”

But most of them are wasting someone else’s money — the governments’, their parents, whatever. There are exceptions of course. But, in my experience, those exceptions aren’t looking to waste their time and money; they want help figuring out how not to.

That is why I present and explain these studies and provide detailed handouts (both in class and posted to the course website after class) for every class. They have everything they need in order to ‘figure out how not to’ waste their time and (their parents’, or the government’s) money. I think that it is important, though, that they make their own decision–that they figure it out. It is important to treat them as adults (and make such expectations known to them), even when they make what is likely to be the wrong choice despite our best efforts to explain to them the grounds on which one decision is better than another, again provided that an individual’s decision is not ruining it for the rest of them.

The third-party effects are sufficient to justify the ban in my opinion. But, really, I don’t see what is adult about wasting other people’s money. I tell them that directly — my job is to make you learn, and to create a classroom environment that optimizes the chances that you will do that. Because that’s what the university (and, ultimately, the government) is paying me to do. If they don’t like that, they can make the adult choice and take a different class — my university, probably like yours, has plenty of classes which are designed to allow students opportunity not to learn anything, if that’s what they want to do.

They have ample opportunity outside the classroom to make bad choices. And ample opportunity within it, too, for that matter — they can drift off (but cold calling helps prevent that), they can not to the reading (again, I have various devices to make that less likely), ultimately they can get bad grades. I am just taking certain choices out of their hands. Their employer will do the same.

(This sort of turned into a Dead-Poet’s-Society teaching statement. My apologies.)

I suppose we might differ on two things, but the differences seem to me to be fairly small:

(1) I think that I sufficiently minimize the possibility of third-party effects by forcing them to sit in positions in the classrooms in which their screens are not visible to other students and forcing them to close the devices if their use of them is distracting another student for some other reason.

(2) I do not think that my job is to ‘make them learn’ (I am likely unfairly nitpicking your language here, but I think that the point is worth making in this way to get at what I suspect is an underlying agreement between us that is important). I think that education is an essentially interpersonal exchange in which they must likewise do their part (that might be unfair language nitpicking on my part). Thinking is not something another can do for you. I assume by entering into my class they have made the adult choice to take on various responsibilities belonging to their part of exchange. I make that clear at the start of the term and throughout, and I do my best to engage them throughout class in order to fend off as much disinterest, laziness, exhaustion from all of the whirl of life, and the like as possible. I think of my job, though, not as making them learn but as provoking them to discover and develop their own talents. The liberal arts are, after all, the arts that free the mind. Yet that requires trusting students to hold up their end of the bargain, with all of the risk of failure that comes with it. Education, like a tango, takes two.

At least at my previous job at a less well-regard state university like yours, this worked very well for the vast majority of students, although I was no doubt benefiting from the fact that most of the courses they took were purely lecture-based whereas I forced them to interact with me and each other in every class. Still, in every class, some set of students would engage with me, their classmates, or the material. I suspect that in part the institutional culture of that university as a whole is to blame (which no doubt reflects the broader culture surrounding higher education in America). The broader consumerist culture of that university made some students act like they had purchased a product that I was there to give them, and their expectation of being passive recipients lead to a reinforcing dynamic where they got less out of the class than others and further tuned out. Thinking, for them, was not the point, and so they ended up not getting anything out of the class.

I think that opposing that culture is an important part of my job since I think that it is detrimental to the university as a whole and to the individual student as well. It does not establish the right mindset for someone to actually learn the skills necessary to be a thoughtful and autonomous adult. I’m in the middle of moving to an institution with a very different learning environment, with different course structures and where the expectations for a student to be self-motivated and self-disciplined are very high and made clear from the beginning. I went to a liberal arts college as an undergraduate with similar expectations. My sense from these experiences is that the difference in institutional culture around expectations for students makes a large difference in how students approach classes. The expectation of an interest in and commitment to learning reinforced that very interest and commitment. I’m not all that confident in my memory of my undergraduate years, though, so I don’t want to make too much of the claim about what it was in fact like. I just want to say that it is what education should be like. I think that it can only be that way if we trust and respect our students enough to expect them to hold up their end of the exchange.

An interesting approach: https://uwaterloo.ca/arts/blog/post/electronics-classroom-time-hit-escape-key

Laptops??? I retired years ago and cell phones were the bane then and now smart phones have to be more ubiquitous than laptops. Laptops were never an issue due to their visibility, but phones?? Yes. Same arguments, same problems, same arguments against and counter arguments apply to smart phones. Just a comment from a fossil as far as technology.

The essence of the issue remains the same and I do agree that the downsides far outweigh the positives here. Such technology (and this goes back to taping classes) allows students to disengage in the present since they can catch up later at home or the dorm (and do they? Maybe or not.).

I feel weird because a lot of the commenters here seem to hold their students in much higher regard than I do. Not because I think they’re idiots or children, but because I think they’re (for the most part) young and inexperienced. Part of our job as educators is not just to teach them material, but also to teach them how to come to teach themselves. Yes, it is true that what works best for each individual person, in terms of work habits and learning style, will vary somewhat. But it’s also true that if you take a very hands off “figure out what works best for you” approach, many of your students are just going to revert to habit. Which means laptops in which they “multitask” and catch up/crunch later. In other words, not only do they not really learn the course material, they also don’t learn how to teach themselves going forward, when they no longer have underpaid overworked teachers who have meticulously curated and prepared every module and policy for their benefit.

Also, if you don’t think most of the stuff people encounter on their laptops and smartphones is *designed* to draw their attention (away from your classroom activities), then you’re frankly naive. Malign me as a “young hotshot” if you want.

I discourage laptops or other electronic devices in my classes, but I also tell them that, when it comes to exams, they’ll only be responsible for things that appear on a handout or things that I write on the board. That is, at the same time that I’ve taken away their preferred method for taking detailed notes about everything being said I’ve also taken away the main reason why, in their mind, they absolutely must take detailed notes about everything that’s being said: anxiety about missing something that might, weeks or months later, appear on an exam. As a result, hardly anyone uses a laptop in my classes, even those students with an accommodation explicitly allowing their use. And, as far as I can tell from comments on evaluations, etc, many of them seem to appreciate the (what’s for them, very rare) opportunity to just be present in class and engage in discussion, only occasionally having to write stuff down.

But my classes are pitched to them as primarily aimed at teaching them how to engage in the activity of philosophy (with the philosophers we read, with me, and with each other), so my telling them not to worry about taking detailed notes makes pedagogical sense to them. (And, of course, this is only possible because my courses are *just* small enough to make it possible, between 30 and 35 students.)

Here’s a question philosophers should be able to grapple with, but I see many avoiding it (here and elsewhere). Or maybe I’m missing something big.

Suppose that, in a classroom of 30, one student has a documented disability that makes it impossible for him or her to take notes by hand, _and_ that this student insists on taking notes directly rather than having a note-taker do so. You agree to accommodate this exception to an electronics ban, but then the student complains that the fact that a laptop ban was in place would signal to the other students in class, some subsection of whom might, in theory at least, care about any of this, that the student has some sort of disability, and that this prospect makes the student uncomfortable. The student insists that you remove the ban this time and not put it in place for any future courses.

On the other hand, you are aware of the fact that, without the ban in place, the amount and sophistication of learning in your course for the remaining students, including (say) six of them who are very keen to learn, will be considerably reduced, and you will be far less effective in doing your job, which you feel passionately about.

Whose interests are stronger here? The interest of the disabled student _in not having other students know_ that he or she has some sort of condition (maybe a sprained wrist, maybe something else) requiring an accommodation? Or the interests of all the other students in class, and all the other people who will ever be affected by whether you have successfully taught the course, combined?

It seems that many people here and elsewhere assume that the answer is _obviously_ the interest of the disabled student in not letting anyone else in class figure out that he or she needs an accommodation easily trumps all the other interests. But even if, for some reason, that one student’s interest in keeping the accommodation concealed is so incredibly important, it’s not obvious to me at least why that should be.

Sorry, that last sentence was written ambiguously. I mean, even if we grant that there’s a very great importance in keeping someone’s disability concealed, and even if the importance of that end outweighs the interests of all the other students in having an environment that allows learning, and so on, it’s not _obvious_ to me why the one student’s interest outweighs all the others’ interests, combined. Perhaps it does outweigh them all, but I at least would like to hear an argument for that conclusion if that’s what’s being implied.

My initial response is to refuse to play with hypothetical situations. I haven’t really found them to be effective argumentative or rhetorical tools. However, I would say that students without documented disabilities requiring a laptop are always free, of their own volition, to choose or not to choose ways of learning that work for them. I’ve never seen it as my job to force them or manipulate them into learning. If after hearing that laptops typically (though not always) detract from learning and if after hearing that their high school learning strategies are unlikely to do them favors in college a student *still* chooses to use a laptop and to try and rely on things like rote memorization then I don’t see it as my duty to trick them into doing something different. They’re adults.

I don’t think this is a hypothetical case, CG. And why is it legitimate to refuse to think through hypothetical cases, anyway?

I share your general aversion to forcing students to learn in a particular way. But the point here is the downstream effect on other students, which we have very good reason to believe is severe.