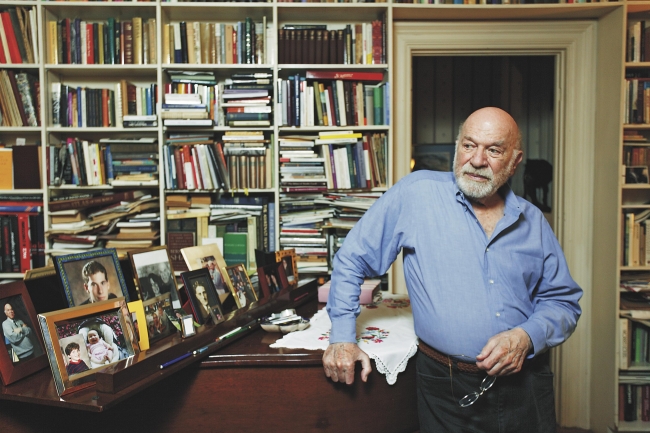

Stanley Cavell (1926-2018) (updated)

Philosopher Stanley Cavell, Walter M. Cabot Professor of Aesthetics and the General Theory of Value, Emeritus, at Harvard University, has died.

Cavell was known for his wide-ranging and tradition-crossing work on aesthetics, language, literature, film, morality, and the history of philosophy, and for his more literary and personal style of writing philosophy.

An undergraduate who studied music at the University of California, Berkeley, and then at Julliard, Cavell turned his focus to philosophy, attending UCLA and getting his PhD from Harvard. He taught at Berkeley for several years, before moving to Harvard, where he taught since 1963.

If you come across links to memorial notices or obituaries elsewhere, please share them in the comments.

Below is an interview with Cavell.

UPDATE:

Ned Hall, chair of the Department of Philosophy at Harvard, shared the following, which was written on June 19th:

I write to share the news of a great loss to our community. Stanley Cavell, Walter M. Cabot Professor of Aesthetics and the General Theory of Value, Emeritus, died peacefully this morning. Professor Cavell was 91 years old and would have turned 92 on September 1st.

This leads to a second way in which Cavell’s thinking in aesthetics was original: the connections he drew between traditional problems of philosophy and issues in the rest of culture. His very first book, and one of his best, is a collection of essays titled Must We Mean What We Say? Like all of Cavell’s works, it is difficult to summarize, but one of its main themes is the connection between the problems that were exercising analytic philosophers at the time—whether language is always ‘public’ or can be ‘private’, to what extent linguistic meaning is ‘conventional,’ whether we can ever know what another person is thinking or feeling—and issues that arose in the practice of the arts themselves: whether an audience can share an experience of a work, or whether we are left to our own private fantasies; whether the traditional art-forms were still ways of creating art, or could now only produce banal copies; under what conditions art can disclose an artist’s experience, and whether it has to.

UPDATE 3:

Abe Stone (UC Santa Cruz) has written an obituary for Cavell at Digressions & Impressions. An excerpt:

Cavell’s death comes at a time when, though some think that Western philosophy has entered a golden age, others of us fear that it may have ended, that there is and will be no next member of the series after Cavell, after Lewis, after Derrida. But then, on the other hand: it also comes at a time when, having tried (but: fairly tried?) doing good, we find, strange as it may seem, that it does not agree with our Constitution. It comes, in other words, at a time when we may ask: why attempt to follow such teachers? Why not reject them and begin anew?

Cavell was a highly distinctive presence on the philosophical scene. I never met him or even set eyes on him, but I read some of his work, mainly on film and literature. It struck me as very interesting, but I found it extremely hard to understand. His mind seemed to work very differently from mine. I wonder if other readers had the same experience.

I have absolutely had the same experience. Even after many readings I find books such as The World Viewed to be extremely slippery, where I have trouble identifying the principal commitments and conclusions. On the other hand, many of the greatest philosophers are difficult to pin down in precise terms although one can discern what they are up to generally speaking. Cavell’s books will continue to be read as primary sources over and above their contribution to scholarship. This should be a testament to his power and influence. In my opinion he was one of the last great philosophers of the 20th century.

It seems to me that in his writings on film and literature Cavell often writes through descriptions of experiences rather than by making arguments. In his work on these subjects he writes from a classical perspective in which philosophy does not need to be sharply distinguished from other humanities in its ability to convey truth.

try this one:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uazq9Fm6gg4

I’ve had this experience too.

My two cents:

Cent 1: Cavell is not a philosopher that answers our questions; (like Wittgenstein, I guess) he is a philosopher who (takes himself to) teache us new questions. That’s partly why it is not clear how, and to what, what he says is relevant. I think he thought, however, that the questions he is trying to teach us–the ones we don’t know how to ask, and don’t see as relevant–are more basic, somehow; so that if we don’t learn to ask them, we might never discover the problems with the questions we are asking (those he does not answer).

Cent 2: There are (at least two ways) into his philosophy: through Wittgenstein, and through phenomenology. The one through Wittgenstein is more straightforward, I think. As a starting point, I would recommend his “The Availability of Wittgenstein’s Philosophy” in his early collection of essays: “Must We Mean What We Say?”

This is excellently put and the advice re: a starting point with Cavell is good.

I first encountered him through Aesthetics, as a graduate student, but as my interest in — and sympathy for — the later Wittgenstein grew, Cavell began to take on a greater significance for my thinking.

Cavell was one of the best we had.

I noticed his pronunciation of “t” the English way not the American.

He advised my senior thesis on Nietzsche and Madhyamaka — he was a smart guy, very perceptive.

He reminds me of Rogers Albritton, also very smart and perceptive, and a great asker of questions. But Albritton wrote little and was easier to understand. Both were keen exponents of Wittgenshtein (as Cavell pronounced it).

That’s how most German speakers would pronounce it too. This is especially true in Austria, where Wittgenstein was from.

Yeah if one speaks German it’s kind of second nature to say it that way. To me at least Wittgenstine sounds only somewhat less weird than Desscartez or Caymuss. I certainly wouldn’t take it to be an affectation.

Other obits:

NYT: https://nyti.ms/2MJqzqF?smid=nytcore-ios-share

NYRB: http://www.nybooks.com/daily/2018/06/20/stanley-cavell-1926-2018/

New Republic: https://newrepublic.com/minutes/149249/stanley-cavell-philosopher-style

LRB blog: https://www.lrb.co.uk/blog/2018/06/20/the-editors/stanley-cavell/

L’Ara: https://llegim.ara.cat/actualitat/Mor-filosof-nord-america-Stanley-Cavell_0_2037396406.html

Liberation: http://www.liberation.fr/debats/2018/06/20/stanley-cavell-the-end_1660627

Suddeutsche Zeitung: http://www.sueddeutsche.de/kultur/nachruf-auf-stanley-cavell-finde-deine-stimme-1.4023979?reduced=true

France Culture: https://www.franceculture.fr/emissions/le-journal-de-la-philo/le-journal-de-la-philo-du-jeudi-21-juin-2018

NZZ: https://www.nzz.ch/feuilleton/nachruf-stanley-cavell-die-eigene-stimme-ld.1316536

Indeed, and that is no doubt the reason Cavell pronounced it that way (as I insist on always pronouncing Italian words with strict Italian pronunciation even if it is unfamiliar to English speakers). But it sounds somewhat mannered to the English ear and the name is not commonly so pronounced by English speakers (you should hear my pronunciation of “cognoscenti”).

It should be remembered that Stanley Cavell, among many others, chose to take part in the Mississippi Freedom Summer in 1964.

Cavell did this, after, not before, the killings of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner.

So, he had no idea whether or not he’d be targeted too.

And yet he went.

I was a TA four years for Cavell and Albritton in Humanities 5. Yes, Albritton was clearer and Cavell sometimes confounding.

I came under Cavell’s spell, though I was never close to him,, and suppose I still am. Besides Wittgenstein’s influence, It’s important to remember Austin’s imortance to him– and also Cavell’s seriousness about scepticism. Perhaps Coira Diamond’s “the difficulty of reality” is relevant.

But I’d just like to imagine Cavell’s relation to movies. He watched a lot of movies, often alone, in the days when movie going was not like going to the multiplex circus overwhelming you with entertainment, but when it was rather more like going to church. You were alone among strangers in the dark, watching, taken up by, a (usually) black and white vision/dream/other way of seeing and being in the world. (I think of Cavell watching Bergman’s “Smiles of a Summer Night.”)

Then you walked out into the daylight, alone, back to your life, ordinary life, reality– though somehow changed. Like Plato’s Cave, like reading The Investigations for the first time, like Austin bring everything down to earth.

That’s my sense of Cavell’s feel for the bewitchment of philosophy, the temptation of scepticism, the return to the ordinary,

the renewal of life –though no doubt i’ve overdone it.

I like those comments, especially about the oscillation between the ordinary and the extraordinary–dreams, movies, skepticism, philosophical transports or trances. Which world should we live in? Wittgenstein is all about this oscillation, which seems unavoidable.

BBCR3 interview with Alice Crary and Stephen Mulhall about political and literary importance of Cavell’s life and work (first 13 or so minutes of a segment titled, “The Working Lunch and Food in History”): https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b0b7my5n