Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Social Philosophy Course

Martin Luther King, Jr. was a visiting professor at Morehouse College in the early 1960’s.* While there, he taught a senior seminar in social and political philosophy. What was on the syllabus?

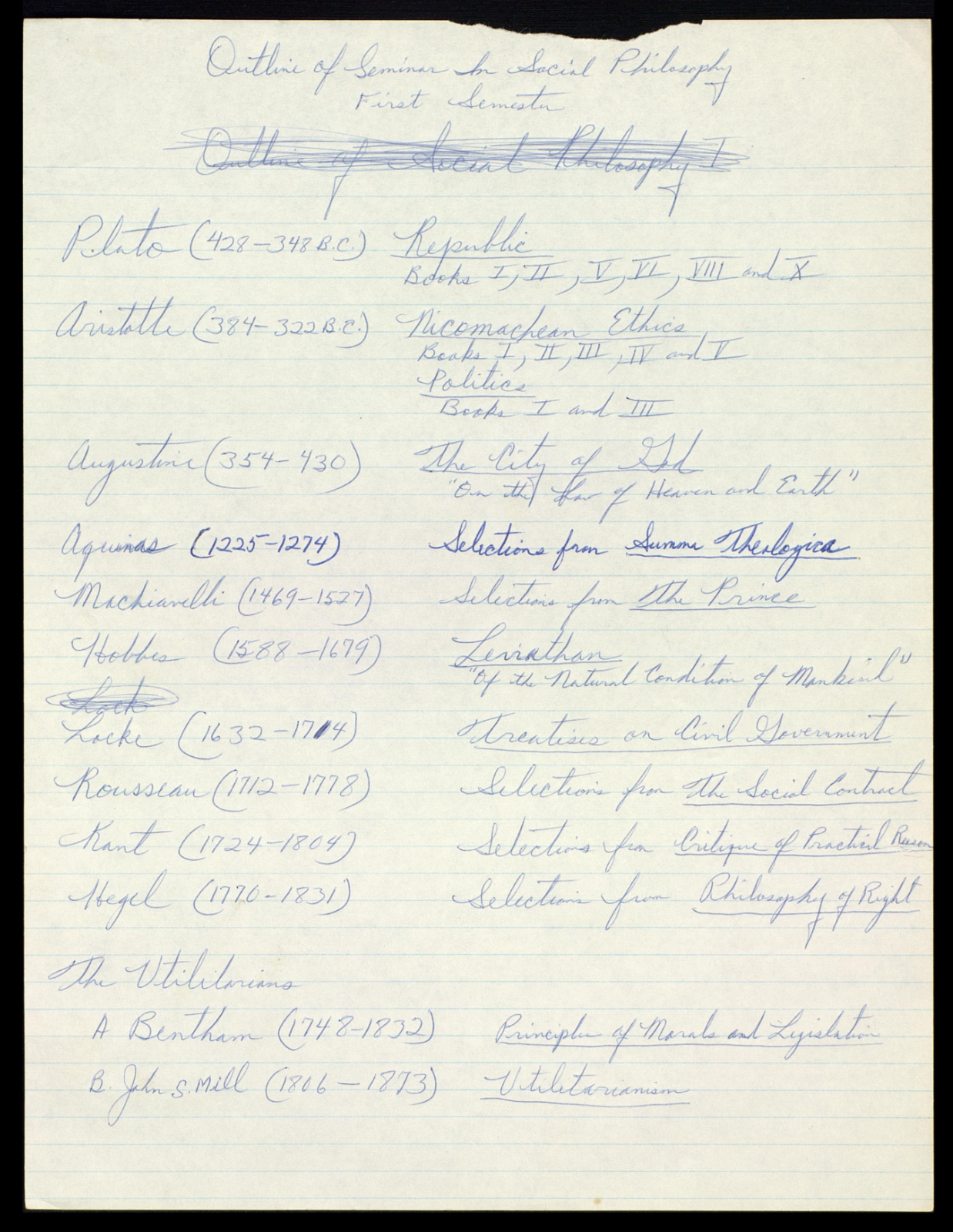

Here’s his outline for the first semester of the course, from the King Center:

He includes material from Plato, Aristotle, Augustine, Aquinas, Machiavelli, Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau, Kant, Hegel, Bentham, and Mill.

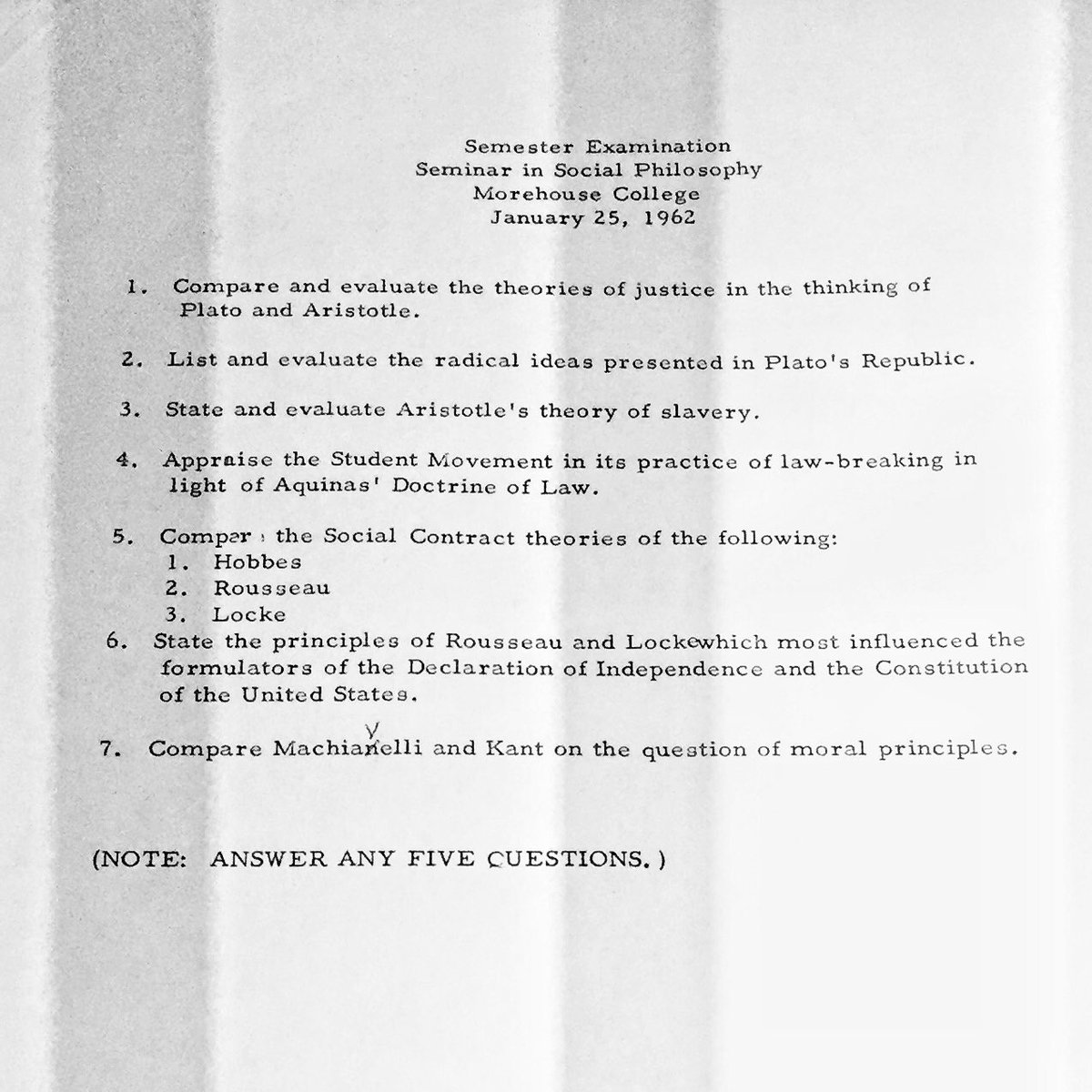

Here is an exam given in the course:

Thanks to various readers and tweeters for bringing this to my attention.

Readers may be interested in the forthcoming collection, To Shape a New World: Essays on the Political Philosophy of Martin Luther King, edited by Tommie Shelby and Brandon Terry (Harvard). Shelby and Terry discussed the book and King’s political philosophy on WBUR’s “Radio Boston” yesterday.

(*Morehouse says the course took place in 1960; the King Center says 1961-62. The exam’s date of January 25, 1962, suggests the course began in Fall 1961.)

[This post was originally published in 2018.]

Now THAT is what a syllabus should look like.

Pretty hilarious to consider the recent posts and comments regarding the Intro syllabus that was posted for our consideration. I wonder if those who supported using that syllabus and who went after critics would have been prepared to tell MLK all about “dead white male” philosophers and how teaching classics “alienates” people of color and other marginalized communities. Then again, I quoted Du Bois who felt similarly to MLK about the philosophical classics and it didn’t seem to have much effect, so perhaps they would have.

Hi Daniel (if I may),

Dr King’s final examination suggests that he may have taught those dead white male philosophers a bit differently than many contemporary instructors do. What types of “radical ideas” in Plato’s Republic do you think Dr. King emphasized to his students? Do seminars on political theory typically discuss Aristotle’s theory of slavery in depth, and if so, do you think they would teach the material in the same way that Dr. King would? Does Dr. King’s fourth question about “law breaking” indicate that he might have emphasized different parts of Aquinas than are often taught? Do you think Dr. King’s discussion of the Declaration of Independence and US Constitution might have differed from how those documents are often discussed in many political theory courses?

A lot of the discussion on this blog has emphasized that *how a course is taught* cannot be assessed by a cursory examination of the reading list. Discussion questions, lecture content, forms of assessment, and instructor behavior, among other things, matter a lot. I conjecture that Dr. King’s political philosophy class, despite containing only dead white men on the reading list, might have been considerably more radical than courses taught now that incorporate contemporary feminist and critical race theory.

Like many readers of this blog, I think many different styles of teaching are *permissible* given what we currently know about student motivation, ability, and so on. Although I am trying to incorporate “non-traditional” authors onto some of my reading lists, I currently teach classes in which students read only dead white men. I don’t think I am doing students harm, and in fact, I think my students enjoy and learn a lot from those classes. Further, I, like many folks who I think you’re criticizing, would not chastise a fellow philosophy instructor for teaching a course with a reading list containing only dead white men, especially because many professional philosophers (a) have little training outside the “canon” and thus (b) need to do independent research if they wish to incorporate philosophical works written by women and people of color prior to the 20th century. In previous posts on this blog, many have simply defended that it is *permissible* to teach a themed introductory course with an non-traditional reading list.. Similarly,, I think many would defend Dr. King’s syllabus to teach a non-traditional political philosophy class with a traditional reading list. And so on for a variety of other course designs.

I was speaking quite specifically about the debate in the comments section after the first post and then the follow-up post, referencing the same subject.

In the course of that discussion it was quite clear that many were *not* simply saying that teaching a course like the one described is “permissible,” but that teaching the classic material today is a mistake, and on several occasions that doing so in some way “alienates” various marginalized communities.

As for the rest of your questions, I don’t know how MLK taught the material nor do I know how many other people do, so to answer you would just be to engage in baseless speculation. All of my arguments in the previous discussion had to do with what I think is appropriate in an Introductory level syllabus, for a course that is very likely going to be part of General Education and may be the only course in philosophy a student takes in their academic career. Given the general thinning out of arts, language, and humane-letters education in college, I maintain(ed) that it is especially important today that students experience Plato, Aristotle, Descartes, Kant, Mill and the like. But from some of the responses I got — one exceedingly confused person described my standard-as-hell, historically based reading list as “bizarre” — you’d have thought I’d made some wild, crazy suggestion.

How do contemporary instructors teach these texts? Your opening sentence requires that you have some answer to this question determinate enough to allow you to interpret King’s test as suggesting that he taught them quite differently. So I’m curious to know what your answer to this question is, and why you think you are in a position to know it.

In my experience as one who teaches more than a few of those texts and who knows plenty of others who teach many of those texts, I can say:

1. King probably has in mind the sexual egalitarianism of the guardian class as well as the abolition of the family and private property in those classes. Those proposals are central to the dialogue and typically a major part of my teaching of them.

2. I have published on Aristotle’s theory of slavery and find it to be an unavoidable and productive topic for discussion. I’m not aware of anyone who teaches Aristotle’s Politics but ignores the defense of slavery. I don’t know how King taught it, but I would not be surprised if he (or many other African Americans) taught it quite differently than I would. But apart from King’s being more interesting than I am, I’m not sure why this would matter; I typically discuss the uses to which Aristotle’s authority was put to defend the exploitation and enslavement of natives in the New World and of Africans (I have also taught Sepulveda and Las Casas’ debate about the ‘Indians’). Is this markedly different from what you imagine King doing? If so, why do you suppose so?

3. The question about law-breaking is hard to avoid if one reads the Treatise on Law, which is often the only part of the Summa that anyone reads in college courses (apart from the 5 Ways). When I teach it, I sometimes explicitly compare and contrast King’s view in the Letter from a Birmingham Jail, which cites it and draws on it but sets out quite a different and more demanding set of conditions for justified disobedience. I’m virtually certain that King would have been more interesting to listen to on this subject than I am, but how different is this than what you have in mind?

4. When I have taught Locke, I have discussed the relationship of the central ideas of the Second Treatise to the Declaration and Constitution. Since I have never taught a course that focuses on either of those American documents, I typically stick to simple points. Someone focusing on the American documents would no doubt teach them quite differently. I’m not sure what dramatic differences you envision between King’s teaching and that of contemporary philosophers and political theorists teaching Locke (or Rousseau, or…). Are you imagining, for instance, that teachers these days just ignore the role of slavery in the American founding and the severe contradictions it involved? On my understanding, such topics are standard.

I don’t think I’m doing anything wildly different from most folks who teach these texts, particularly not from people who specialize in the history of philosophy. I’m sure King’s class would have been different than mine, but I’m not seeing any reason to think that he approached them any differently than I do.

You must be supposing something quite different either in King’s teaching or in standard contemporary teaching. What is it?

Hi Daniel,

I think there’s some important context which might change the interpretation that someone may otherwise draw concerning Dr. King’s syllabus. This course is being taught at a historically black college to a student body that was predominantly *black. Given the year and material presented, what seems clear to me is that Dr. King was not just trying to teach these students philosophy, but teach these students the philosophy that they could use to communicate across racial divides with the white population. There was, for lack of better term, a language of the justification of segregation and white supremacy. There was an education level, and an academic background, that people in power at the time (and still, now) used. In order to engage and fight those people, it is possible, and I think likely, that Dr. King recognized he needed to teach his students the same historical sources (with clearly a different focus). He likely believed that there was greater power in engaging people who would justify their beliefs by appeals to principles of Hobbes, Rousseau, Bentham, Mill, etc, by engaging directly with the ideas of those very thinkers. To claim “an unjust law is no law at all” is to leverage the ideas of Augustine, a language white religious oppressors understood, against the ideas of Plato.

I have little doubt that in today’s climate, where higher education is somewhat readily more available to African Americans (than it was in the early 1960’s–I want to be clear), Dr. King would be a strong advocate for a diversified syllabus. I have little doubt that he also recognized that a resistance that understands the language of its oppressors is likely to be stronger and more effective than a resistance that does not.

*I have little knowledge of the racial demographics of historically black colleges in the early 60’s.

The suggestion that King regarded these texts as containing simply the voices of his oppressors would seem to require a pretty cynical interpretation of the Letter from a Birmingham Jail, where he explicitly endorses aspects of Aquinas’ views about law and obedience yet also articulates a view subtly different from (and rather more restrictive, as it happens) than Aquinas’. The natural, non-cynical interpretation would be that he learned from reading Aquinas, both in finding some things to agree with and in refining his own views in response. It is of course possible that he really believed that Aquinas et al. were of no value to his students apart from the strategic rhetorical value of being able to quote the oppressor against himself. But we’d need some reason to think so, and none has been given. Perhaps King was just not wedded to a fundamentally Manichean view of the world that divides it up into the oppressed, who are the ally, and the oppressors, who are the enemy; perhaps King was capable of recognizing the moral complexity of people and ideas. That used to be a hallmark of American liberals, but alas, those days seem to have passed.

//simply//

That’s your word, that’s not what your interlocutor said or implied.

You are a better man than me Matthew. I read Kaufman’s comment as trying to be a “gotcha” against “the woke left.” About as worthy of response as a trolling on Twitter. I think if anyone doesn’t see the massive under enrollment of people of color in philosophy classes and the major itself, they simply are in denial. And if they do but think nothing needs to change, well that’s the very definition of insanity. There’s far more going on in these numbers then can be explained by disparate college attendance alone.

A rather odd definition of insanity.

Both sides of this debate seem wedded to the assumption that there’s one best way to teach “intro” or other classes, but disagree on what “best practices” are and why. This is pretty obviously false. There are a lot of very good ways to teach most survey classes and a lot of different reading lists that might work. Also, you can’t possibly teach every thinker you’d like to teach and there are many different considerations both for and against most people you might include on a syllabus reading list. In an ideal world where we have infinite time to get up to speed on every interesting thinker in human history, our classes last for at least 4 semesters, and all our students received a solid high school education and have no distractions we might teach students Plato, Aristotle, Kant, Descartes, Confucius, al-Ghazali, the Bhagavad Gita, Gandhi and who knows who and what else. But most of us have a very limited amount of time to familiarize ourselves with new stuff, students have so many distractions and wildly varying levels of preparation for college, and we get 15 weeks. Given that I wouldn’t assume that anyone who doesn’t put Confucius, Zhuangzi, al-Ghazali or whomever on an intro syllabus must be some sort of knuckle dragging racist or backwards chauvinist. But by the same token I think it quite possible that someone who teaches an intro or a survey class on political philosophy that’s missing Plato, Aristotle, Kant, Descartes, Mill or even every single one of those guys has still done an excellent job teaching that class. I certainly wouldn’t say they’ve done their students a disservice. I’ve known profs who stubbornly put some classic on their syllabus every single semester even though they can never motivate any real interest in it in their students or get them to take much away from it. Now that strikes me as a clear disservice.

The exam is very interesting. It looks to me as if MLK deliberately set it up to give his students two strategic options :

1) To address the burning issues of the day via a critical dialogue (sometimes, one suspects, a ferociously critical dialogue) with a set of famous political thinkers of the past, all of them (at it happens) dead white males.

2) To discuss these thinkers in a relatively abstract, theoretical and historical way if they felt uncomfortable with option 1).

Why do I say this? Well students have to answer seven out of five questions only two of which (maybe only one of which ) could not be answered competently by a student who studiously avoided any mention of contemporary issues.

Thus King was fostering the development of radical ideas and challenging his students to apply the political philosophy that they were learning and developing to the present and whilst *at the same time* allowing them to pass the course with credit if they did not feel like taking up the challenge.

Why did he do it this way? I suspect a respect for the autonomy students. Did King have a political agenda? Of course he did. He was passionately committed to a wide range of radical causes. Was he out to attract recruits and supporters to the civil rights cause? Of course he was, especially as he was teaching at what was in those days was probably not just an Historically Black College but a Black College tout court. But he only wanted recruits and supporters who had come to the cause out of a reasoned conviction, not because they had been intellectually pressured, bamboozled or bedazzled by a charismatic professor. Thus the course seems to provide ‘spaces’ for those who might dissent from his agenda, either because they didn’t agree with him or because they were just not interested. His OBJECT was to help students to think for themselves about a range of political issues and to acquire a working knowledge of a range of political classics. His HOPE was that these autonomous critical thinkers would wind up agreeing with him and committing to the cause. But he did not want to compromise their autonomy in order to secure that agreement.

I think you mean 5 out of 7, not 7 out of 5. Just kidding… 🙂

Aargh! Like I said, I stink as a proof reader. Yes of course, five or maybe even six out the seven questions could have been answered without contemporary reference.

I totally stink as a typist and proof-reader. My fourth paragraph should read:

Thus King was fostering the development of radical ideas and challenging his students to apply the political philosophy that they were learning and developing to the present whilst *at the same time* allowing them to pass the course with credit if they did not feel like taking up the challenge.

Me, too. See previous joking post to your site. But overall, your comments are very good and I agree entirely. Could anyone assign all those readings nowadays? Not in my experience after 30+ years – one anthology, maybe.

Thanks for this!

But I’d love to know: what was in the SECOND semester??? 🙂

Hegel and the utilitarians?

And I second the thanks — fascinating!

There is a reason Hegel is on the list…..because King says that Hegel is his favorite philosopher. Here is a link for those interested.

http://www.autodidactproject.org/other/hegel-mlk2.html

Just a question that I suspect some of you can answer. How widely known would King have been to his students at the time? Would there have been any increase in “fame-level” that might have occurred it it were 1960 vs. 1961=62 date? Would anyone have set there and thought, Man, I’m getting a course from Martin Luther King?

My exams are way too easy.

When I look back at exams and syllabi people have shared with me from mid 20th century, I’m always struck by the degree of independent work required of the student. Often a list of books is given, as opposed to specific pages to be read on specific dates, and these books form the content of lecture (which may include discussion or Q&A, or a separate section for discussion might be assigned, like a lab). Exams might require multiple essays focused on major themes, requiring sophisticated synthesis as well as selection of relevant evidence. The experience must have been quite different from what many students experience today, with detailed lists of readings, notes, outlines, and steps to be taken in completing assessments, not to mention things like rubrics and learning outcomes.

This is an excellent and much-overlooked point, Laura.

I think we need to keep it in mind when assessing evidence that university does a very poor job of teaching students anything important. Unfortunately, the research generally seems to have been done quite recently, when things had degenerated to the point we’re at now. King’s course took place within living memory, and I’m old enough to have seen things at about the halfway point between then and now. I think the slide has been pretty consistent, given that the rigor of the courses that generally seem to have been around in the early 1990s was about halfway between what we tend to offer now and what we see in this syllabus.

If only the long arc of the undergraduate universe could also bend in the right direction!

I don’t think the arguments that a typical undergraduate education is worthless are incorrect, but I think they are incomplete. They tend to discuss only the way things are now, but often implicitly treat that as though it represented everything a university education could be. We could do so much better, even though our incoming students tend to arrive with much worse preparation. But the incentive structure in postsecondary education is positively counterproductive here.

It’s notable that in 1960, only 41% of Americans had graduated high school, and only 7.7% had graduated college.

https://www.statista.com/statistics/184260/educational-attainment-in-the-us/

There were fewer institutions of higher education then (many prominent public universities didn’t exist, like UI-Chicago, UM-Baltimore County, George Mason University, and half the UC’s and UT’s) and many of the universities that did had far fewer students, even proportional to the population.

The few people that did attend university in 1960 were likely among the best prepared students from the most rigorous high schools, rather than constituting a signification fraction of the graduating class from nearly all high schools.

Additionally, the Federal Work-Study Program aimed at enabling low-income students to work part-time while attending college was only founded in 1964. It’s likely that almost all students at almost all colleges in the mid-century were able to devote a higher fraction of their time to studies than a large number of contemporary students.

Good point, and a nice set-up to a variant on the Repugnant Conclusion. Suppose that you could increase the proportion of people who attend university as far as you like — even to 100% — but that, as you get closer and closer to that percentage, the amount of time the students spend thinking about the material they’re learning decreases exponentially. When you hit 100%, the total amount of time each student spends thinking about all the material covered in his or her entire time at university is one millisecond. And so on.

What we really need to know in the real world though is whether the proportion of time that the best students spend studying and the quality of their preparation and the quality of the education they get has significantly declined. It seems quite possible to me that it has not.

If not, we’ve really made a Pareto improvement (or very close to one): Good students are still good students and get good educations (however much of that is based on unearned privilege), while not so good students, including those who are not so good for unfair reasons to do with poverty/not richness etc., at least get some education.

And that possibility is consistent with it seeming to almost all lecturers that there has been significant decline because the vast majority of their students are worse prepared and have less time and so on. We need hard data here.

My preference, for what it’s worth:

1. We begin by raising standards in the K-12 system, to ensure that most people never have to go to college. Most jobs do not really need what college or university uniquely prepares people to do. This approach saves everyone, especially the poorer members of society, plenty of time and money.

2. This will greatly reduce the number of people who need to attend college, and the total cost of providing all such people with a great college education. That will make it easier to invest in finding the people who will benefit the most by going to college, and benefit society the most by doing so. We can then take steps to ensure that they make it to college, if they cannot afford to do so already.

3. Meanwhile, we can do our best to give all K-12 students, particularly those from poorer backgrounds, the rigorous teaching and other resources they need to excel at what they do.

I seem to remember seeing somewhere that the amount of time university students spend on their studies has indeed greatly declined. But whether or not it’s clear that it has, there is ample evidence of things going very wrong at university. For instance: twelve years ago, I contacted the bookstore in alarm when I saw that they only had seven copies of the required textbook for a course I was about to teach (the course had almost thirty students). The bookstore manager told me that most students don’t buy the texts. I at first wondered whether they are just finding online copies or borrowing the book from the library. But I later was told by one of my students that, even though he had taken a dozen philosophy courses before mine, he had never read a word of any of the readings in any of his courses until my course, and that he only started in my course because I made it impossible to pass otherwise.

I’m pretty sure that this could not have been standard practice decades ago, for the very simple reason that students used to get chucked out of school for being bad students. That no longer seems to happen.

Your proposal re K-12 may have some or a lot of merit, but I wonder how realistic it is in the U.S. context, where so many employers require bachelor’s degrees for jobs even though they’re probably not necessary in a lot of cases. Even if K-12 education were greatly improved, one would still have to get businesses to change their practices in this respect, which would likely prove difficult. I suppose it may be worth trying, though.

Also, wouldn’t you have to ask more than one student why many of them don’t buy the textbook in the bookstore? Textbooks are often v. expensive, and they may find alternatives, such as buying a used or older copy online. As for the student who had taken a dozen philosophy courses without doing any of the reading, do you think this is anything other than an extreme case? (If it is something other than an extreme case, I’d say that something may be pretty wrong at Rutgers, and perhaps not only there.)

I’ve talked to quite a few people at different schools (though not perhaps the most elite schools), and have heard similar things. So I think this is a general trend and not some local aberration.

Also, some students I’ve spoken with transferred in from other colleges and universities and said that those other places tended to be less rigorous.

You’re right that it would be useful to find out from more students whether they make a point of doing the readings. I’ve asked a few students about this and they’ve told me that some of the students they know of do the readings while others don’t. A few years ago, I was introduced to one student who had distinguished herself by taking a full courseload while working 40 hours per week, and she still managed to get straight-A grades. I asked her how she managed to do it, and she said that it was all a matter of taking ‘the right courses’. When I asked her what she meant by that, she explained that, in the ‘right’ course, you could get good grades just by writing essays based on what was discussed in class without having to do any of your own reading.

About that student who told me that mine was the first course for which he’d done any reading, out of dozens: he had transferred in from a community college, as I recall, and might have taken half his courses there. I’ve taught at community colleges and tried to make my courses just as rigorous as mine are now, but perhaps things have changed over the last twenty years or so. Anyway, even if this guy was the only student I’ve ever had who had made a point of never doing his readings, the fact remains that he somehow didn’t get booted out of school for that after years of doing it. How is that possible? I think I have fairly good grounds for thinking that at least several people out there don’t really care all that much if some of the students they give passing grades to just do this. In fact, many things people have written here on Daily Nous and on a couple of Facebook groups I belong to more or less admit this.

In all honesty, it looks like he was half-assing it on some of these exam questions. Now, maybe he’d say he was busy with out-of-class projects, but so are we all.