Philosophical Diversity in U.S. Philosophy Departments (Updated)

The vast majority of philosophy departments in the United States offer courses only on philosophy derived from Europe and the English-speaking world. For example, of the 118 doctoral programs in philosophy in the United States and Canada, only 10 percent have a specialist in Chinese philosophy as part of their regular faculty. Most philosophy departments also offer no courses on Africana, Indian, Islamic, Jewish, Latin American, Native American or other non-European traditions. Indeed, of the top 50 philosophy doctoral programs in the English-speaking world, only 15 percent have any regular faculty members who teach any non-Western philosophy.

Given the importance of non-European traditions in both the history of world philosophy and in the contemporary world, and given the increasing numbers of students in our colleges and universities from non-European backgrounds, this is astonishing. No other humanities discipline demonstrates this systematic neglect of most of the civilizations in its domain. The present situation is hard to justify morally, politically, epistemically or as good educational and research training practice…

Many philosophers and many departments simply ignore arguments for greater diversity; others respond with arguments for Eurocentrism that we and many others have refuted elsewhere. The profession as a whole remains resolutely Eurocentric. It therefore seems futile to rehearse arguments for greater diversity one more time, however compelling we find them.

Instead, we ask those who sincerely believe that it does make sense to organize our discipline entirely around European and American figures and texts to pursue this agenda with honesty and openness. We therefore suggest that any department that regularly offers courses only on Western philosophy should rename itself “Department of European and American Philosophy.” This simple change would make the domain and mission of these departments clear, and would signal their true intellectual commitments to students and colleagues.

That’s Jay Garfield (Yale-NUS) and Bryan Van Norden (Vassar) in “If Philosophy Won’t Diversify, Let’s Call It What It Really Is” (New York Times). They add, “Of course, we believe that renaming departments would not be nearly as valuable as actually broadening the philosophical curriculum and retaining the name ‘philosophy.'”

Meanwhile, the latest issue of the American Philosophical Association Newsletter on Asian and Asian-American Philosophers and Philosophies is focused on the status of Asian philosophy in the discipline in the United States.

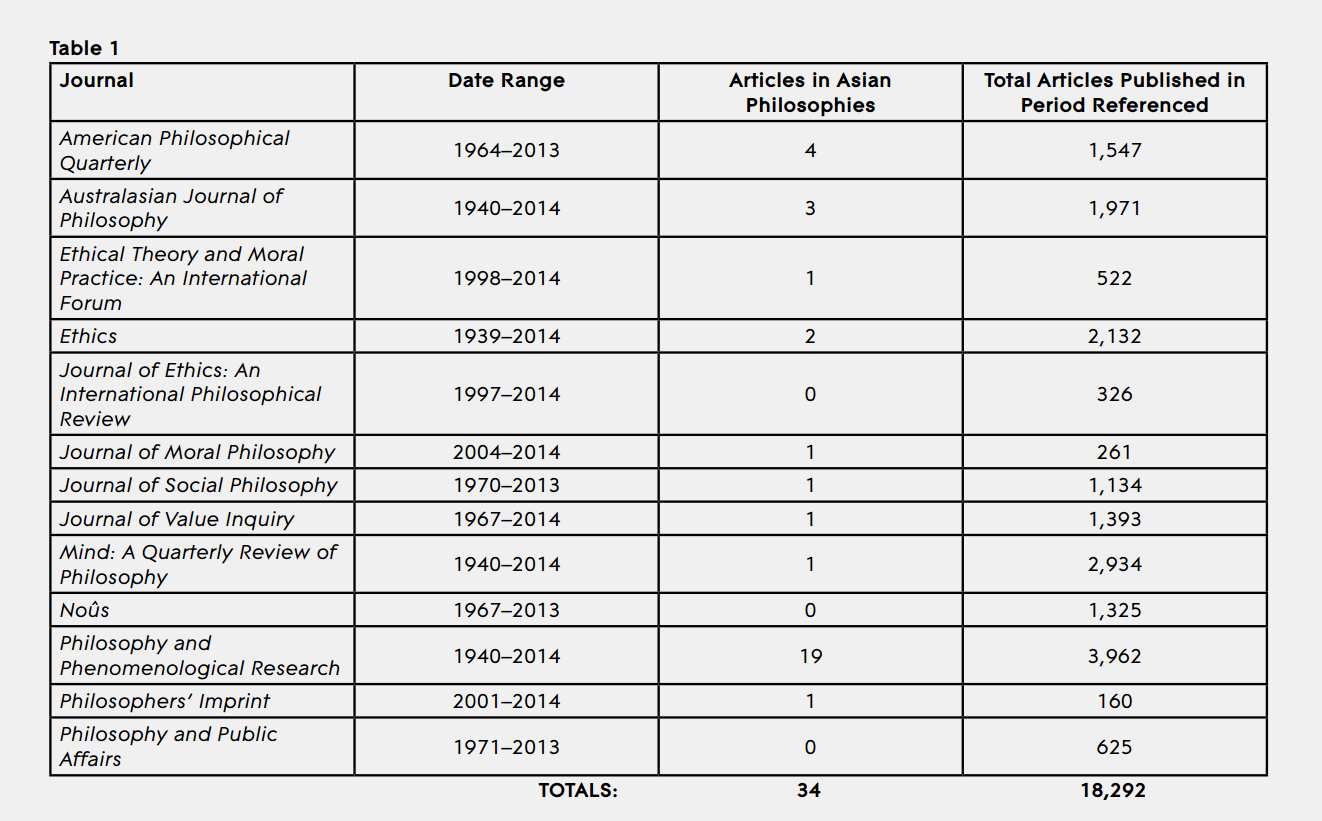

Amy Olberding (Oklahoma), guest editor of the issue, presents some data on how often work that engages substantially with Asian philosophy appears in a number of “mainstream” journals. The numbers are astonishingly small:

(from “Chinese Philosophy and Wider

Philosophical Discourses: Including

Chinese Philosophy in General Audience

Philosophy Journals” by Amy Olberding)

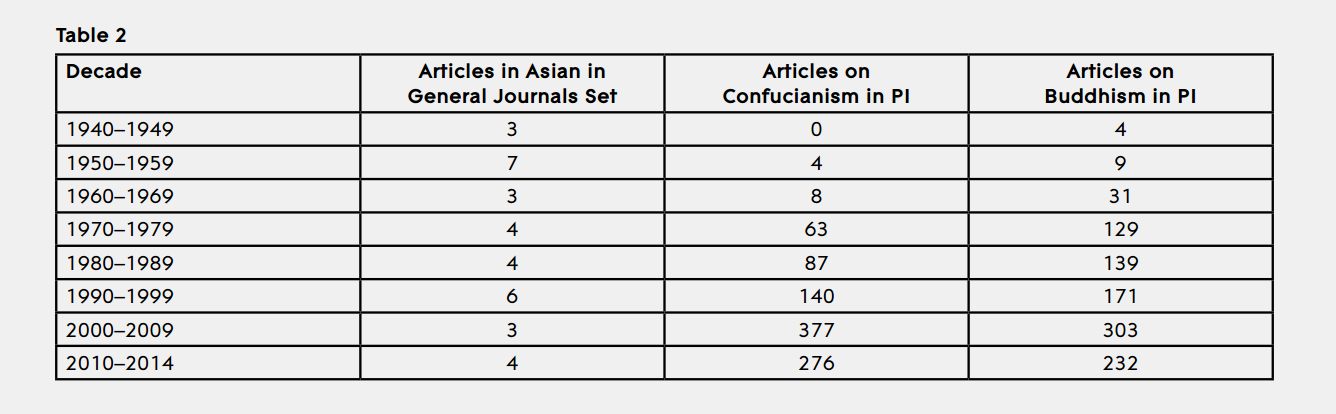

She notes that while the number of total articles on or engaging with Asian philosophical traditions has increased over the past 70 or so years, that is owed to the establishment of specialist journals. There has been virtually no increase in the number of articles in that category published in general journals, as is apparent from Table 2, which compares that number with the number of such articles in Philosopher’s Index (PI):

(from “Chinese Philosophy and Wider

Philosophical Discourses: Including

Chinese Philosophy in General Audience

Philosophy Journals” by Amy Olberding)

One downside of this is that if specialist journals are where nearly all such work is published, these “conversations risk becoming wholly private, uncoupled from wider philosophical discourses.”

Olberding countenances various reasons for these numbers. One is that “most of these journals receive submissions in Asian philosophy comparably rarely,” according to their editors. Yet this is likely the product of a self-reinforcing process, as she explains:

Low submission rates are, however, in many respects unsurprising given that the percentage of philosophers both trained in Asian philosophy and likely to produce general audience research is small. But here, too, it would be hasty to think that this is the only or principal problem. After all, work in Asian philosophy has dramatically increased in recent decades and yet there is no corresponding sign of this in the general journals. Insofar as these journals are not seeing an increase in submission rates of work in Asian philosophy, this may owe to the journals’ track records. That is, these journals’ historically low publication rates for work in Asian philosophy will have considerable influence on the likelihood of their receiving submissions in the area. Most basically, philosophers of all stripes will incline toward submitting their work in the journals they most frequently use in performing their research. Since the general audience journals rarely publish in Asian philosophy, specialists are simply unlikely to identify their work as viable for these outlets. More potently, few philosophers will submit their work to journals that rarely or never publish “work like mine” or, indeed, are perceived to exhibit a bias against “work like mine.” There is, in other words, a vicious cycle we cannot discount: the absence of Asian philosophy from a journal’s prior issues will depress submissions going forward, producing yet more issues in which the work is absent.

Importantly, she highlights the professional consequences of these publication facts:

We inhabit a world in which myriad professional goods—goods ranging from winning jobs to achieving tenure and promotion, as well as other markers of status, such as acquiring research funding or winning awards—are significantly influenced by one’s success in securing publications in the best outlets possible. Insofar as the profession counts publishing in the most “prominent” or “top” general journals as one of the most direct pathways to “prominent” or “top” status for individual philosophers,13 we should not expect anyone working significantly with Asian philosophical sources to succeed in this way.

The current issue of the newsletter also contains articles by David B. Wong (Duke), Erin M. Cline (Georgetown), Alexus McLeod (Connecticut), Yong Huang (Chinese University of Hong Kong), and Bryan Van Norden (Vassar). You can read the whole thing here.

UPDATE: Commentary elsewhere:

- The “All Lives Matter” response— “Huge stretches of European philosophy… are also neglected in many of the top 50 PhD programs”—at Leiter Reports.

- The “Don’t Be Presumptuous” response— “One complicating factor the authors do not address however is that in many cases there has been a long and contentious history surrounding the question whether the category of ‘philosophy’ is one that representatives of non-European intellectual traditions would even want, or would have wanted, to adopt as a description of what they are doing” — at the blog of Justin E.H. Smith.

- The “Be More Radical” response—“Diversity talk only gets us so far. The gaze needs to stop being so neutral. It needs to be deeply critical and decolonizing”—at the blog of John E. Drabinski.

- The “Red Herring” response—“While there is, indeed, a fairly narrow historical canon in professional philosophy, this canon is not central to philosophical education, philosophical method, and professional advancement/success within analytical philosophy”—at Digressions & Impressions.

- The “Up Periscope” response—“Far too many philosophers… are… scared of the cooties they’d pick up by actually knowing the first thing about the history of almost all the other humanities disciplines”—at John Protevi’s Blog.

- The “Pardon Me, Gentlemen” response—“Even as the arguments are made that ‘Western’ is an inadequate descriptor of ‘philosophy’ in the U.S…. mentions of that same tradition’s constitutive patriarchy and heteronormativity are more or less relegated to ‘et al’ status” at ReadMoreWriteMoreThinkMoreBeMore.

“If Philosophy Won’t Diversify, Let’s Call It What It Really Is”

A brilliant idea! The best I’ve heard for a long time. It could be a real game-changer.

“Indeed, of the top 50 philosophy doctoral programs in the English-speaking world, only 15 percent have any regular faculty members who teach any non-Western philosophy.”

Does anyone know the source of the information for this claim?

In an op-ed in the LA Times, Eric Schwitzgebel (UC Riverside) says: “In the United States, there are about 100 doctorate-granting programs in philosophy. By my count, only seven have a permanent member of the philosophy faculty who specializes in Chinese philosophy.”

One could teach a subject at the graduate level without specializing in one’s research on it, so, while related, this doesn’t quite answer your question.

This is what I was wondering as well. I incorporate non-Western philosophy into my classes. I am certainly not a specialist in any area of non-W phil. I doubt I would have been counted (how would they know).

I am very ignorant of non-Western philosophical traditions and perhaps this post will only expose my ignorance. Perhaps someone who knows non-Western traditions better will comment on my post.

However, I am under the impression that the best arguments are generally to be found in Western philosophy. When I last read Confucius, just to take an example, I don’t recall finding any arguments at all. That doesn’t make Confucius unworthy of study, but it does make him a lot less philosophically (as opposed to anthropologically) interesting to me.

Confucius certainly does not look much like a philosopher if one approaches him with expectations based on experiences with philosophers in the Western tradition. But what if instead of starting by trying to identify specific claims and supporting arguments, we take a different approach? If you had to pick one thinker who exerted the most influence on Chinese culture, whom would it be? Confucius is undoubtedly at least a strong candidate. Ok, what explains this? What did Confucius say, and how did this affect later thinkers? Isn’t this the same kind of question we ask about, for example, Plato?

I sometimes tell students that “what is philosophy?” can itself be a good philosophical question. When we approach Confucius, we could always decide that he does or doesn’t count as a philosopher by trying to find content that fits our concept of philosophy. But we could also consider broadening our concept of what should count as philosophy.

This response seems a little underwhelming. Philosophy and “what exerts influence on culture” are just not the same thing. After all, religion is not philosophy, but religion (in the “West”, Christianity) has influenced culture vastly more than philosophy. (Of course, religious thinkers sometimes make philosophical claims, and philosophers sometimes make claims about religion, but they’re still not the same thing.) If it’s really true that Confucius doesn’t give arguments, then he’s really doing a different thing than the authors studied in philosophy departments in the US. (I mean, even Nietzsche–not someone studies much in US departments–gives arguments from time to time, and he self-consciously claimed to be doing “something else”, not philosophy.)

If Confucius seems opaque, I encourage you to read the sizable secondary literature or introduction-style texts that address him. But he is, perhaps perversely, the least compelling example for making a case that argument is absent from early China – authorship of works commonly identified as “by Confucius” is not simple so I’m not even sure what “reading Confucius” may mean here. More to the point, there’s just no credible case to be made that, e.g., Xunzi, Mengzi, or Zhuangzi have no arguments. Part of the problem here is that people know so very little about Chinese philosophy that they don’t even know where to look when looking to discount it. Sorry to sound cranky but the fact that conversations about these issues immediately devolve into discussions of whether there’s any THERE there – any philosophy IN the rest of the world – is part of the problem. Armchair speculation about this among those who have almost no exposure to any of it is really of limited utility and I share Jay’s and Bryan’s reluctance to accept that we need to demonstrate (again and again) that there is a THERE there.

Amy is right. I am no expert on Chinese philosophy, but I include texts from Mengzi and Wang Yangming when I teach Ethics. I do so not in order to fill some non-Euro quota on my syllabus, but because these two philosophers have seriously argued and worthwhile things to say about moral sentiments. Looking at Indian and Buddhist philosophy, Nagarjuna’s claims in his MMK (I’ve taught Garfield’s translation) are as profound and as well argued as any found in the Western canon. May I also recommend that doubters take a look at the interesting work of Graham Priest on Buddhist logic.

The Analects may not be the best source if you’re looking for explicit argumentation. The text is not polemical with respect to any philosophical position or worldview. It’s a universe unto itself. For argument, try the Mozi or some of the Zhuangzi, for example. That said, to understand or even to notice the argumentation found in there one will need to understand the broader cultural and intellectual background. Here, Confucius is indispensable. I recommend Chad Hansen’s A Daoist Theory of Chinese Thought which highlights the polemical and critical aspect of early Chinese thought.

To me the issue would not be Asian philosophy but just philosophy. The arguments for Taoism can be found in Sufism; the arguments for Eckhart’s philosophy can be found in Buddhism; the Upanishads are argued for by Schrodinger, etc.. It is the ‘perennial’ philosophy that is not taught and this can be found everywhere. It could easily argued that Asian philosophy normalises on ‘nondualism’ such that Zhuangzi and Lao Tsu would belong in the same school as Spira and MacFarlane. A million websites discuss and endorse this view and arguments range from Nagarjuna’s total destruction of extreme views to Brown’s simple ‘calculus of indications’ to Bradley’s argument against the reality of distinctions. They are all largely ignored by the curriculum.

I cannot think of an argument more important to philosophy than Nagarjuna’s, the subject of Jay Garfield’s ambitious book and no doubt part of what he had in mind by his criticisms, but this is not Asian philosophy. It is just philosophy. It is as relevant in Kansas today as it was in Tibet in the second century. It is not just Asian philosophy that is ignored but an entire world-view wherever it appears.

It appears more clearly and regularly in Asian philosophy, however, and so is less easy to avoid. Roman Christianity saw it as an heresy and largely still does and so European philosophers have usually been wise enough to say little, while Islam is famous for putting its its supporters to death in horrible ways. This problem of censorship and fear is usually absent from Asian philosophy but the philosophy would be no more local to Asia or anywhere else than quantum theory. Which is not to say that Asian philosophy is not a study in its own right.

It would be more accurate to say “We therefore suggest that any department that regularly offers courses only on Western philosophy should rename itself Department of European and *Anglo*-American Philosophy’.'”, since both Latin America and “Native America” could be interpreted (wrongly, in this case) to be included in the expression “American Philosophy.”

And African-America. (That is, African-American philosophy would also be wrongly interpreted to be included in the expression “American Philosophy” in this case.)

Actually, now that I think about it, it might be good to just put “White” somewhere in the new department heading.

This is a great idea.

And the mathematics department should be renamed, “Department of White Male Mathematics”.

This will be an excellent way to get more women and racial minorities into math.

Yes, because there aren’t any relevant differences between mathematics and philosophy for explaining why attending to non-Anglo/European traditions is important in the latter but not the former. But, if we’re going to be glib about it, I suggest that someone who purports to be an abstract entity should stick to what they know and butt out of human matters altogether.

This whole exchange seems sort of unserious, but if it’s not I would be interested in seeing the relevant differences spelled out. (I don’t mean to implicate that I doubt they exist.)

Perhaps rename philosophy departments as the “Department of Whitewashed Intellectual History and Practices”?

“The vast majority of philosophy departments in the United States offer courses only on philosophy derived from Europe and the English-speaking world.”

This is only plausible if we regard philosophy of science and of the specific sciences (physics, cognitive science, biology…), and by extension those sciences themselves, as the property of Europe and the English-speaking world. That buys tacitly into a pernicious cultural relativism about science that really needs to be avoided.

Great example of using philosophy of science to shield the cultural Eurocentrism in philosophy departments. If one is really worried about avoiding cultural relativism about science, then philosophy of science should be in a separate department from where metaphysics, ethics, aesthetics, history of philosophy, etc. are taught. It’s very simple: Plato’s theory of forms, or Kant’s noumenal realm is no more scientific than discussion of the Tao or Brahman. So it’s unclear why philosophers of science seem ok sharing department spaces with people who talk about the theory of forms but not the Tao. If anything, philosophers of science should push for more diversity in philosophy departments, so that it is clear which aspects of philosophy are culturally intertwined and which aren’t; then we can truly appreciate the non-culturally-relativistic features of science. Otherwise, philosophy of science is being used dubiously to give a veneer of universality to highly cultural specific aspects of Western philosophy.

I don’t understand this reply. I took Wallace to be claiming that the philosophies of science–philosophy of biology/physics/etc.–which are offered in most philosophy departments, are not tied to any particularly European or English-speaking outlook. I don’t know whether that’s true, but I didn’t read the post as trying to give “a veneer of universality” to other “highly culturally specific” areas of philosophy. It’s just a claim about the philosophies of science and philosophy of science more generally.

It’s simple. Imagine an Anglo-American department didn’t have any philosophers of science in it; it only has people who do metaphysics, ethics, history, etc. Then it is natural to say that department is culturally biased. Add philosophers of science to the department who don’t focus on any Western philosophy directly; so it is clear they are simply doing meta-science, not anything specificially Western. Now the fact that the metaphysicians and ethicists share the same department as the philosophers of science makes it seem as if the former are also doing something universal. Philosophy of science (and logic, etc.) is used as a cover to protect the department focusing on stuff which is obviously Western focused.

This is even more so when the same people do philosophy of science _and_ metaphysics (say, Lewis), or philosophy of science _and_ ethics (say, Putnam), as if the categories from both are interchangeable, and so the concepts of Western philosophy are somehow universal. Wallace writes as if philosophy of science is neutral in these issues of diversity. But it isn’t neutral if it is functioning (not intentionally or explicitly) as a cover. It’s great that philosophy of science aims to be neutral; but to achieve that it has to clearly dimarcate itself more from the culturally biased parts of the philosophy department.

@JDRox: you read it as intended.

I don’t think I said anything about cultural Eurocentrism one way or another. It was a straightforwardly factual comment: since a large fraction of philosophy departments in the US offer courses in general philosophy of science and philosophy of various specific sciences, it’s only true that “the vast majority of philosophy departments in the United States offer courses in philosophy derived from Europe and the English-speaking world” if we regard philosophy of science, and by extension (and pace JT below) science itself, as so derived, which we should not. So the claim made is false. Whether philosophers of science should move to another department, fight for diversity in other bits of philosophy, or anything else, doesn’t affect that argument.

The claim made by the authors is not false. You are reading it in a certain way so as to make the authors sound imprecise or uncareful – which they were not in their piece. They didn’t say: “the vast majority of philosophy departments in the U.S. offer courses ONLY in philosophy derived from Europe…” What they said in the claim, understood in the context of their piece, is clear: “the vast majority of philosophy departments in the US offer courses in philosophy [understood as philosophy which has counterparts in others traditions] derived ONLY from Europe..”

It is an important fact that there are classes taught in philosophy departments which are clearly universal and which aren’t Western (philosophy of physics, logic, etc. — what all is included in that “etc.” is an interesting, open issue). But it just unhelpful to make it seem like the authors somehow deny or overlook this fact. A philosopher of science might feel wronged that their work is being unjustly implicated in the author’s criticisms of current philosophy departments. Fine. Then let those philosophers of science themselves make clear how their work is distinct from the purely Western basis in metaphysics, ethics, etc. in their departments. Let the philosophers of science be as critical of their colleagues in their departments who claim to do universal metaphysics or ethics; otherwise, it is not these authors unjustly implicating them, but the philosophers of sciences implicating themselves through their silence.

You only make the authors’ claim true by interpolating a qualifier (“[understood as philosophy which has counterparts in others traditions]”) which is nowhere in their article and is in contradiction with their proposal to rename departments.

The ethical obligations of philosophers of science (or mathematicians, for that matter) towards curriculum diversity in those parts of a university’s curriculum that are culturally localised has no bearing on whether their own work is culturally neutral.

The qualifier is nowhere in the article because the qualifier is the whole context of the article. The majority of a philosophy department is not concerned with philosophy of physics or logic, or philosophy of science; that is a fact (this is no claim about the importance of phil physics). The majority is concerned with questions about the human condition which are culturally infused. Most of the time when “philosophy” is used it is meant to pick out that culturally infused part, and that is what normally the professors and lay public talk about, and which the authors are referencing.

If we are going to talk about philosophy of science in the context of the article, it is about more than the ethical obligations of philosophers of science. Obviously philosophy of science has the science part, and the philosophy part. Where is the philosophy part coming from: from pure reason? This makes sense when talking about phil of physics or logic.

But what about sciences which are about humans: psychology, anthropology, etc? In these cases the philosophy part and even the “folk psychology” part are often culturally infused with ideas imbued through the Western texts, and treated as if it were universal common sense. Russell, Carnap, Quine did this all the time, and they were given a pass because they were stellar logicians and philosophers of science, as if their pure, pristine logical mind is relevant, and their lack of knowledge of other traditions is irrelevant, even when they are talking about the mind, or free will, or ethics. This is to gain the sense of universality on the mind, free will, etc. through, in Russell’s phrase, theft rather than honest toil.

“Most of the time when “philosophy” is used it is meant to pick out that culturally infused part, and that is what normally the professors and lay public talk about, and which the authors are referencing.”

That conception of philosophy is as limiting, in its own way, as the conception that the only culturally-infused part of philosophy should be the part infused by Anglophone/European philosophy. It often seems tacit in these discussions of the philosophy curriculum and is one main reason why I tend to make these interventions. It is, I suppose, at least clarifying to see it made explicit.

(Apropos the question of whether the authors’ article tacitly restricts to culturally-infused philosophy: I notice that they don’t propose renaming departments “the department of Anglo-American, European and culturally-neutral philosophy”. I don’t see how it’s possible to read their article without assuming either that they’ve forgotten about philosophy of science entirely, or included it in Anglo-American and European philosophy.)

I am not defending the practice of equating philosophy with culturally infused philosophy. Yes, these debates and public discussion would be better off if there was a clear sense that there is already a culturally neutral philosophy (phil physics, logic) in phil depts, and which is distinct from the culturally infused philosophy in phil depts. I agree making this distinction explicit is important, and it would bring out better just which parts of phil dept are culturally infused and which are not. It would be great if more philosophers wrote about that to raise people’s awareness of it.

The vast majority of work done in modern epistemology, metaphysics, and philosophy of language also have little to do with any distinctively European way of looking at the world and are heavily influenced by mathematics and the sciences.

How is it determined that, say, current metaphysics in Anglo-American departments has little to do with anything distinctively European? is it because the metaphysicans aren’t racists, and so wouldn’t let any cultural biases interfere with their work? Of course that is a non-starter. Is it because they use logic and philosophy of science? That’s doesn’t prove it either. Not denying current metaphysics is influenced by universal things like logic and science. Am denying current metaphysics is ONLY influenced by universal things like logic. A great deal of current metaphysics is also culturally baised, insofar as it is influenced by Aristotle, Leibniz, etc. Not denying there are universal elements in Aristotle, et al. But there is no way to tell which parts of Aristotle are universal without connecting it other traditions. Don’t care how famous and brilliant Russell or Lewis are: I am not going to just take their word that the parts of the Western tradition they use are the universal parts. There has to be an independent way of checking that. No amount of logic and science will do that by themselves. Nothing short of a pluralistic department can do that.

Too many 20th century philosophers, including the greats, hid behind philosophy of science as a way to make their philosophy seem universal. That is not going to cut it in the 21st century.

Isn’t the more interesting question whether it’s true, justified, and interesting?

Of course, the issue is whether a given metaphysical view is justified. To determine that we have to whittle away the parts of the view which are universal, and which are not. The push for diversity is one important way of determining if a given view in philosophy, Western or non-Western, is justified, a way to remove the unjustified parochial part from the justified universal part. To ignore pluralism in the name of reasons and justification is like (to use a famous example) trying to determine if what is said in a newspaper is correct by checking other copies of the same edition of that paper.

Doesn’t the answer to that question depend on the proper and actual determinants of truth, justification, and interestingness? And wouldn’t supposing that one’s cultural outlook makes no difference to either what is in fact true, justified, and interesting or what one takes to be true, justified, and interesting beg the question in favour of the thought you sought to defend in the first place?

“This is only plausible if we regard philosophy of science and of the specific sciences (physics, cognitive science, biology…), and by extension those sciences themselves, as the property of Europe and the English-speaking world. That buys tacitly into a pernicious cultural relativism about science that really needs to be avoided.”

That is a rather obtuse and uncharitable reading of Garfield and Norden’s point. Even if it were to be conceded that the philosophy of science (broadly construed to include subfields devoted to specific sciences) and the sciences themselves are not bound to the intellectual tradition of any particular culture or region, they are right to draw attention to the fact that the philosophical contributions of non-Anglo/European traditions w.r.t. other areas of philosophy have been unjustifiably neglected by most Anglo/European philosophers out of sheer ignorance, prejudice, or some combination of the two. (Predictably, but nonetheless disappointingly, many of the pointed questons about and objections to their proposal here take the form of something like ‘The works in X tradition don’t seem to be truly philosophical, even though I haven’t bothered to carefully examine them myself’.) Their proposal is for those inclined to remain ignorant about non-Anglo/European philosophies and disengaged with works in these traditions to call the spade a ‘spade’ and openly declare their parochial philosophical outlook, and I’ve yet to see anything to suggest that this is in anyway unreasonable.

In any case, it’s not clear this concession should be made in the first place. First, I don’t see why rejecting cultural relativism about the sciences entails that the philosophy of science as practised in most Anglo/European departments isn’t too narrowly confined to the Anglo/European philosophical tradition or that philosophical study of science wouldn’t benefit from the insights of thinkers in other traditions. Science may rise about cultural differences, but whether this is true of the philosophical tools and methods applied by Anglo/European philosophers to answer philosophical questions about science is clearly another matter. Second, not only should we disentangle science from the philosophy of science in this regard, there is also reason to do the same for certain scientific disciplines like psychology, where many studies only or disproportionately involve WEIRD participants due to pragmatic considerations. While the conclusions of physics can straightforwardly claim to be universal, it is less clear whether all other sciences can do the same.

Garfield and Norden may be right to draw attention to a particular issue; that’s compatible with them making false claims in their discussion of that issue. (It’s not uncharitable to point out when specific claims are false; it might be uncharitable to draw inferences from that falsehood towards their larger project, but I was silent on that project.)

It’s entirely plausible that people would do better philosophy of science if they learned more non-Western philosophy; but there are lots of things people could learn that would improve their philosophy of science, without broader conclusions following from it. (I think most philosophers of physics could usefully learn more perturbation theory, but that doesn’t translate to a cultural bias.) For the sake of argument (though only for that) let me concede the point about psychology; I work in philosophy of physics, and I find accusations of cultural bias in that context more bemusing than anything else.

2 Quick thoughts.

Why the focus on graduate programs alone? I’ve taught in several undergrad philosophy programs and ALL had a member who taught non-western philosophy (even if they didn’t publish exclusively on non-western topics). I think the percentages of undergrad departments offering non-western phil. would be significantly higher than 15%.

Now, if I were today to apply to grad schools in my AOS, I don’t believe more than 15% of programs would be a good match. Why would we expect or demand a higher percentage for Chinese Philosophy?

Just so people know, Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal is about to publish a dedicated issue on Asian bioethics, and we also have other articles by Asian scholars and on Asian traditions in the pipeline. We are very excited about this!

Could someone who knows, since I do not, link to or recommend some resource which is persuasive as to why I or anyone else working within the Western philosophical tradition ought to invest my time in examining the thought of some other tradition? What insights do they bring to bear on the perennial questions which necessarily, if these different traditions are to be considered as having something in common (and thence deserving of a common name), ground the philosophical endeavor in the first place?

E.g., why is there something rather than nothing, what is the human being, how should life be lived, what do we mean by “knowledge”, and so forth.

Joel Kupperman has an article: “Why Ethical Philosophy Needs to Be Comparative.” It might go part of the way to answering your question.

Brian K ,

I have been very impressed in this regard by Hagop Sarkissian’s work on Confucianism. Here is one example: http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/p/pod/dod-idx/minor-tweaks-major-payoffs-the-problems-and-promise.pdf?c=phimp;idno=3521354.0010.009

Early Daoism. Sorry for the typo.

I’d say that only serious comparison shows which problems are truly perennial. As to persuasive literature… Chris Fraser has done work on knowledge in early China that might interest you. Chad Hansen has an interesting essay on how Chinese metaethics can help us build a naturalist normative theory (Ethics in Early China; there’s more good stuff in the anthology). Don’t know if this is your cup of tea. For an insight on how to live, the Zhuangzi. Hans-Georg Moeller has great stuff on the text and Early Daoi in general. Confucian role ethics could be another area worth your attention. Cheers!

Brian K – I’d be glad to oblige.

Anything on the perennial philosophy would do but it is not easy to suggest a starting point since it depends where we’re starting. Jay Garfield’s book on Nagarjuna would be one recommendation although it is is monstrously complex and there are simpler and clearer explanations.

The reason for investing some time would be that the perennial philosophy represents a solution for philosophy and is not just a collection of intractable problems. This solution has never been falsified, hence ‘Perennial’. Googling ‘nondualism’ should generate a large library of material. Perhaps Professor Radhakrishan’s ‘Philosophy of the Upanishads’ would be useful. Bradley’s ”Appearance and Reality’ is a favorite of mine for his elegant prose.

The point of the study would be that metaphysics is solved in this other philosophy so it represent a means of progress. I wouldn’t expect you to believe this assertion but it is demonstrable. Not seeing this would be the price of the partisan curriculum that Garfield complains about.

Perhaps I misunderstand the meaning of “perennial” in this context, but it would seem weird to claim that only the western philosophical tradition has raised and investigated the “perennial questions.” That would make such questions seem “culturally and historically specific” rather than “perennial.” Or, if there are truly perennial question to which only the western tradition has productively contributed (such that those in the western tradition can confidently decline to invest their time in learning about anything outside that tradition), then that sounds like a claim for western superiority. Disclaimer: I have serious doubts about the existence of perennial questions. But I don’t see how someone can both (1) believe that they exist and (2) not already assume that a diversity of cultures have contributed meaningfully to them and that these various contributions are worth the investment of our time to learn about (if we really intend to dedicate our time toward the full and robust investigation of perennial questions).

Perhaps people don’t know because they’ve never thought to look, but the SEP has a number of articles on non-Western traditions, as well as more specific disciplinary questions (Indian Epistemology, Indian and Tibetan Buddhist Ethics, the Kyoto School, etc). There’s often a great deal of topical overlap with the kind of “real philosophy” that gets trotted out as the standard in these discussions. As a starting place and a source of procrastination, they might be helpful to people who are looking for that sort of thing.

It is worth thinking about what we are really asking for here. To my knowledge, there are good philosophers and researches in asian philosophy in many universities, just not in the philosophy departments. People doing asian philosophy are usually affiliated with religious studies, divinity school, east asian studies, south asian studies, etc. It is just some kind of unfortunate division that separates people apart (in different departments). And there are good papers and books published, just not in most “philosophy” journals. So we need to be a little more cautious here. I am not sure whether it is a well-justified idea that asian philosophy should be included in philosophy departments; and I am not sure the best way to diversify philosophy is to diversify philosophy within philosophy departments.

To me the real problem is that people in philosophy departments do not pay enough attention to non-western philosophy, and some people even devalue the non-western philosophy. The urgent thing to do is that people should be aware of other approaches to philosophy and open their eyes to those approaches, recognizing that there are good philosophers doing non-western philosophy in departments other than philosophy. We should also be more inclusive in terms of courses, publications, conferences, and researches. Even if they may be called “interdisciplinary” studies, we should tell ourselves that they are all real philosophical studies.

I think this increased pressure on diversifying philosophy is more symptomatic of the way people in US, esp. people coming from the wave of immigration since 90’s struggle with their own identity and reasons for being in US and Western Europe. Philosophy in Asia (esp. China and India) is in many ways increasingly taking on the shape and form of “Eurocentric” analytic philosophy, both in its approach to contemporary problems and to its own history. I think philosophy has a choice – go the way of CompLit departments – with no standards as to what still counts as literature, and no standards of canon, thought, or rigor of work – but very diverse – to the point that there is no point. Or it can go the way of linguistics where white male jewish generative grammar is generally thought to be the way to go and diversity comes from ideas and interests of people of whatever ethnicity. One more thought – the opinion piece is so condescending and self-righteous, it almost made me angry. And not only because it confuses doing philosophy, contemporary, with research in history of philosophy – I demand more Byzantine, Russian and Hungarian philosophy since, as far as I can see, in comparison to those, Asian and African philosophy are overrepresented!

Chinese universities tend to teach Western and Chinese philosophy as separate paths or specialties. Both are taught at Philosophy Departments (Marxism tends to be the third path). Why not try something similar?

Philosopher John Drabinski, Professor of Black Studies at Amherst College, has written a response to Garfield and Norden. I posted about it on Discrimination and Disadvantage: http://philosophycommons.typepad.com/disability_and_disadvanta/2016/05/drabinski-on-diversity-neutrality-and-philosophy.html

I grade my students’ papers by the quality of the arguments. So, it is presumed by me that quality of philosophy depends on quality of arguments.

It is an observable fact, moreover, that the argumentation in non-Western (and Continental) philosophy is more enthymematic. (Not always, but typically.) Moreover, enthymemes are normally poorer quality arguments.

So normally, non-Western philosophy comes out as poorer in quality.

And poorer quality philosophy deserves less attention in the philosophy curriculum.

Having said that, however, I think it would be good to distinguish between “dialectics” as a discipline (where quality of argumentation is supreme).–versus a broader notion of philosophy, where “philosophy” means something like “worldview.” Philosophy, on this broader conception, SHOULD be more inclusive. But this is not to say that “dialectics” has no place as an academic discipline.

It would be unsurprising, by the way, if dialectics currently ended up more “white.” Becoming skilled in argument requires education, and educational opportunities are diminished for those who are not white. But the solution is not to devalue argumentative skill. The solution is to ensure more educational opportunities.

So let a thousand flowers bloom in “philosophy.” Just make sure that one of the flowers is dialectics.

I’m not sure if one could observe any such empirical facts by tossing out speculations from the armchair–other than, perhaps, certain facts about the armchair. I highly suspect that you are exactly what Amy Olberding had in mind when she wrote her comment above.

Olberding explicitly spoke of those who thought there were “no arguments” in the non-Western canon. Clearly that view is indefensible.

My view is rather that, for the most part, the arguments there are more enthymematic.

And I object to your armchair assessment that my assessment is merely from the armchair!

“My view is rather that, for the most part, the arguments there are more enthymematic.”

“It is an observable fact, moreover, that the argumentation in non-Western (and Continental) philosophy is more enthymematic. (Not always, but typically.) Moreover, enthymemes are normally poorer quality arguments.”

Where is the argument for these premises?

“I grade my students’ papers by the quality of the arguments. So, it is presumed by me that quality of philosophy depends on quality of arguments.

It is an observable fact, moreover, that the argumentation in non-Western (and Continental) philosophy is more enthymematic. (Not always, but typically.) Moreover, enthymemes are normally poorer quality arguments.

So normally, non-Western philosophy comes out as poorer in quality.

And poorer quality philosophy deserves less attention in the philosophy curriculum”

This is a very poor enthymeme. It is hard to establish the scope of “not always, but typically,” so you may disagree, but I hope that a quick read of this article and related ones will show you that at least one non-western tradition typically proceeds according to rigorous argumentation. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/logic-india/

A quick thought: I notice that they did not mention any philosophy of religion journals. I know that Faith and Philosophy (perhaps the top phil of rel journal) has done issues on e.g. Hindu philosophy in the past, so perhaps that would alter the data. (Which isn’t to say that I’m convinced that this is a major problem, it’s just an observation.)

In response to Amy Olberding’s analysis, the paucity of work that engages substantively with Asian philosophy in mainstream journals has a rather simple explanation: junior philosophers specializing in some area of Asian philosophy too need to get published so they can secure tenure, and there are risks associated with submitting work in Asian philosophy to mainstream venues with no real track record of publication in that area. The conversations in any subfield of Asian philosophy these days are highly technical and presume familiarity with the relevant literature, so it’s only natural that juniors would seek to enter those conversations where they actually happen: in the specialist journals. I agree that in the long term that breeds insularity, but for small subfields that’s often the only way to keep the conversation going (and sometimes the subfield alive).

I don’t think this isolationism is good in the long term, though, but without journals like Philosophy East and West, Journal of Chinese Philosophy, Journal of Indian Philosophy, and a handful of others, I doubt these subfields would have survived, let alone thrived. Is it time to bring some of this great work into the mainstream? Of course! But don’t expect that everybody will rush in and read Nagarjuna, Mozi, or Gangesa if their ideas were all of a sudden engaged with in the mainstream journals.

Christian,

I’m not sure I’m reading your objection correctly, but I well grant that junior folks have little incentive to try their hands at “mainstream” journals. Indeed, I think the risks of that prohibitively high given that publishing rates are so low for work in Asian philosophies in these outlets. I don’t think this does explain the wider phenomenon though. As I note in the article, there is no increase evident in the general journals to correspond to the increase in the specialist outlets – surely that’s not all due to prudent strategy on the part of junior scholars? I find it hard to believe the explanation really is that simple and do discuss other likely issues in the article.

I likewise don’t expect people to flock to Mozi if he shows up in general journals. However, every *single* time this sort of conversation comes up in philosophy, people (some well-meaning, some not) chime in to ask where they might find all this non-western philosophy being touted as useful. This leads me to think that barring interventions via general journals, people simply do not and will not encounter the work (pace Garfield’s and Van Norden’s argument, they’re unlikely to encounter specialists roaming their departments!). My hope is that if it does get better included in general journals, it will simply become less mysterious, less hidden, and more familiar. And, if you simply take the comparisons with Aristotle seriously, that there are highly technical specialist conversations happening need be no barrier to more generally accessible work appearing elsewhere and in less devotedly specialist outlets.

Amy: Don’t get me wrong. I greatly appreciate your efforts in highlighting the disparity between how Asian philosophy shows up to insiders (certainly, as a flourishing enterprise) and its perception by the mainstream of our profession. Those are valuable statistics, indeed, and no doubt going forward will help many in negotiating whether and where to submit papers that, while engaging with Indian, Chinese, or Buddhist ideas and arguments, are aimed at a mainstream audience. I simply pointed out what I take to be a matter of fact: that small and emerging subfields in philosophy (and, I imagine, in all other disciplines) often need their own publishing outlets to get established, let alone thrive. Obviously, I agree that half a century or so of serious systematic engagement with Asian materials has amassed enough evidence that these philosophical traditions have much to contribute to our present concerns, and are worth engaging with for more than just purely intellectual reasons. Your reasons for why this should happen, and the benefits that our profession would accrue thereon, are perfectly clear.

My initial objection was about the diagnosis of the problem, not the proposed solution. Anecdotal stories about desk rejections may be a symptom of lingering parochialism in our discipline, but I don’t think they explain the wider phenomenon. The increase in Asian philosophy output is largely a factor of the hospitable environments provided by the specialist journals (and, of course, the top academic presses), and should be recognized as such. Should work in Chinese virtue ethics or Buddhist philosophy of mind go mainstream? Of course. Are the general journals the best venue for that? It depends. If a journal signals that it intends to broaden its scope, then yes. If not, it’s wasted effort.

Is it the case that had general journals been more hospitable we would not have seen new ones, like Comparative Philosophy, spring up? I don’t know. But now that Mind, for instance, has announced it would publish work in all areas, periods, and traditions of philosophy relevant to its scope, we have good reasons to be optimistic that things will get better as we go forward.

The other side of “diversifying philosophy” is including other researches into the territory of “philosophy”. And this may not be welcomed by those who are included. I do not know other traditions but in China, some philosophers doing Chinese philosophy hesitate to think of themselves “philosophers”. The reason is simple: they think “philosophy” is western by nature. And there is no term in Chinese directly translating “philosophy” and the current translation was from Japanese in late 19 or early 20 century. There is even an ongoing debate in China about whether the term “Chinese philosophy” is legitimate. Some people think the so-called “Chinese philosophy” should be more like the “history of thought” or “history of ideas”, and they really resist the term “Chinese philosophy”.

I am not taking a position here, just mention another layer of complication.

The difference between appearance and reality is an example of a philosophical problem that has been considered by both Eastern and Western philosophy, and that may be further illuminated by studying both Eastern and Western traditions. There are arguments made by Vedanta and Buddhist philosophy about the nature of the difference between appearance and reality that are just as compelling as those that can be found in the work of Western philosophers such as Plato, Schopenhauer, Bradley, Russell, and Putnam.

Whenever conversations take place about the relative merits of different philosophical traditions or related concerns about the focus of the discipline in English-speaking universities, at least a few reactions from (presumably) philosophers trained in the mainstream Anglo-American tradition of the following form seem to pop up: *disclaimer about the speaker’s substantive ignorance of X philosophical tradition*, *seamless transition to pontification about the general character of the X philosophical tradition*. The obvious question seems to be, “Which aspect of the famed rigor of analytic philosophy teaches that this is good scholarly practice?”

This may be a tangent, but some of the discussion above seems to be about style. Stanley Cavell has sought to claim thinkers like Emerson and Thoureau as philosophers, but I wonder where this project stands and goes and how it relates to the education of professors of philosophy? When I think of writers like James Baldwin, Ta-Nehisi Coates or June Jordan amongst many others, I find the thinking deeply philosophical, but philosophic in a certain key. Where are spaces for this thinking? Departments of American Studies? Again, American philosophy was briefly mentioned in the article, but I find the question of philosophical style important in a broader way, even though I use American thinking as illustrative here. Can one think philosophically and yet not be consider a philosopher? Cavell has argued that there is a question worth considering here and I wonder how this line of thought relates to the current discussion.

As I explained in more detail on the leiterreports, the IEP article on Wiredu that Van Norden and Garfield link to is a total mess It’s outrageous to link to that as evidence that Wiredu belongs in the canon alongside Hume. Wiredu often gets this kind of treatment from advocates of more diversity in the canon. But given the kind of evidence of his greatness that is always offered, I find it hard to believe that the diversity advocates have read him carefully and assessed him based on philosophical standards.

To avoid a couple of misunderstandings: (a) Wiredu could be a great thinker with bad expositors. I’m not objecting to him, but only to how he’s used by people like Van Norden and Garfield. And (b) These points are independent of Van Norden and Garfield’s claims about Confucius, Vedanta thinkers, and other non-westerners.

The sheer and near-total ignorance of Indian, Chinese, and Tibetan philosophy on this thread is not surprising. What is surprising is the parochial attitude people are taking to material they have not even read, far less attempted to comprehend.

Well…. no. On second thought, it isn’t surprising at all. Scandalous, deplorable, and gratuitous; but not surprising.

I do not agree with people who claim that, somehow, only Greeks “investigate these problems through careful, extended, and rigorous argumentation.” I find that highly unlikely and the bits I know of Indian and Chinese philosophy indicate otherwise. However, here are some questions:

1) Philosophy is, in one way or another, a theoretical discipline. If you disagree with this, of course, the rest of the question is irrelevant. Every theoretical discipline assumes a certain basic conceptual framework which includes methodology (what counts as argument), some basic commitments (say, to there being matter), and some basic agreement on what constitutes a problem (say, that if a conclusion conflicts with experience, we have a problem worth thinking about further), and so on. This conceptual framework is not static or precise, but it is almost always historically rooted. Concepts, problems, issues, do not come from nowhere. And the way in which we think – whether within the framework or about it – often involves, and generally is most illuminating when it involves, thinking about its own history. This is because philosophy is not only theoretical discipline – it is also a cultural product and a matter of tradition. THe way philosophy is done in US and Europe, goes back to Plato and Aristotle – this is its tradtion. The path is often complicated, involving various “revolutions” and reconceptualizations, rediscoveries, and translations, but there is little doubt that that is so. It also so happens that these two were already classics in Ancient times and we have their works (well, Plato’s for sure – Plato and Plotinus are I think the only two Ancient Greeks we have complete works of). The study of most other Ancient GReek and ROman figures is much more neglected outside specialists. In any case, from this point of view, Indian Chinese, Persian, or Korean philosophy simply is neither as relevant nor as illuminating for people working in the Western tradition. These are traditions that have often quite different frameworks, their own histories and so on. To bring them to relevance inevitably leads to what I like to call making them into bad versions of contemporary philosophers. It is often a kind of funny exercise. It happens in Western philosophy itself – redescribing Aristotle in terms of contemporary philosophy of mind or language, for example. Forget that his conceptions of matter, basic causal structure of the world, or of the role of experience are not shared by us anymore. But at least in his case, we can go back to the text and come to understand it without such distortions, partially because, despite all this, his methodology, basic concepts and so on are predecessors to what we do. And this is usually more interesting too though often, obviously, he comes out of only antiquarian interest (though still interesting – his physics is completely rational and completely wrong!).

2) when people talk of Indian, Chinese and so on philosophy they often talk of old or Ancient texts, history. But they talk about as if it should be taken account by people who do contemporart philosophy. But where does this “should” come from? Nobody thinks people should take into account the hisorty of Western philosophy – just that it might be good if they did. For reasons in (1), I do not see this should. How about contemporary Indian philosophy?

3) Personally, I would like to see more Indian and Chinese philosophy in particular. Done in the way we do Greek philosophy -as proper history. But the arguments that are used to argue for it I find off-putting – as if these traditions were only interesting because of identity issues.

I cannot speak to other kinds of neglected “non-Western” philosophy, but I have always had a rather robust side interest, and love, of ancient Chinese philosophy (my AOS is philosophy of cognitive science). For those expressing a skeptical note about what Chinese philosophy has to offer, or would like some pointers, here are some topics/readings, which are comparative, and I have found very interesting.

1. Compare and contrast Confucian and ancient Greek virtue ethics. I confess to finding the views of Kongzi (Confucius), Mengzi, and Xunzi to have many strengths over the views of Plato and Aristotle. For a great read on the topic, see Jiyuan Yu’s (2007) The Ethics of Confucius and Aristotle: Mirrors of Virtues, Routledge.

2. Compare and contrast Confucian and early Modern discussions of human nature. In a nutshell: Mengzi is Rousseau, and Xunzi is (a more plausible version of) Hobbes (more or less). The parallels here are striking. Xunzi anticipated Hobbes’ original position argument by centuries (or so it seems to me), and Mengzi and Rousseau even use some of the same metaphors (e.g. moral development and nurturing plants). An excellent paper on this topic is Eric Schwitzgebel’s (2007) “Human Nature and Moral Development in Mencius, Xunzi, Hobbes, and Rousseau”, History of Philosophy Quarterly.

3. Compare and contrast Doaist skepticism about reasons and argumentation Cartesian and Humean skepticism. The Inner Chapters of Zhuangzi are truly bizarre, and an absolute joy to read. There are interesting issues of meta-level indeterminacy in how to interpret his views, or rather, non-views. See David Wong (2005) “Zhuangzi and the Obsession with Being Right.”, History of Philosophy Quarterly.

4. Views in the Confucian tradition on moral self-cultivation. See PJ Ivanhoe (1993) Confucian Moral Self-Cultrivation.

5. Finally, I second the above comment that Hagop Sarkissian is doing a lot of excellent work on a whole host of topics: http://www.hagopsarkissian.com/

If you have never read Chinese philosophy, pick up Van Norden and Ivanhoe’s Readings in Classical Chinese Philosophy (it contains excerpts from the main 7 figures from the classic period). I think AC Graham’s Disputers of the Doa is still a great introduction to careful philosophical discussion of the ideas from the classic period.

Disclaimer: I am not an expert on ancient Chinese philosophy (it’s more like a secondary AOC). So I would encourage others with more background than myself in non-Western philosophy to offer up other suggestions as well.

Yes, Sarkissian’s work is really cool! Glad to see it getting mentioned around here.

I want to second JBR’s basic point, and take it further. My AOS is moral psychology. I think it’s fair to say that anyone seriously interested in moral psychology ignores the major classical Chinese philosophers at their own peril. The classical Chinese philosophers are, quite simply, among the greatest moral psychologists the world has to offer.

The difficulty I have with the discussion is the idea that ‘Asian’ philosophy is something philosophers can choose to study or ignore.

If by ‘Asian’ philosophy we mean that of the Upanishads, the Tao Te Ching, the Conference of the Birds, the Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way and the countless other available texts that endorse the same view, then we are talking about a quite different set of claims about the world, a different way of solving philosophical problems and a way of coming to a knowledge of truth and ‘Being, Consciousness, Bliss’. We are talking about understanding consciousness and psycho-physical phenomena and solving metaphysics once and for all. We are not talking about just doing the same old thinking in a different language. .

To see this as a matter of geography or culture would simply compound an error. It would be a matter of taking a whole different approach to describing, understanding and investigating the world and our place in it. , one that does not fall foul of the all the problems associated with the ‘European’ philosophical mind-set but offers solutions and understanding. Where a theory is a challenge to our view it should not matter where it originates but whether it is any good. If we do not know whether it is any good and yet dismiss it from our studies on the grounds of it country of origin then this would be a matter of basic scholarship.

If departments are renamed to make clear that they are not studying the whole of philosophy this would be helpful and might even clear up some confusion. It would not solve the underlying problem that motivates the target article, however, which would be the failure of the department to know its enemy and its inability to explain what it wrong with the solution to philosophy that it offers to us. I wonder how many of those who feel that Asian philosophy is not important would be able to list even five claims that it makes let alone be able to refute them. The authors seem right to suggest we should name the department by its mind-set and not continue with a name that suggests it studies all philosophical ideas equally and openly. The discussion here makes it completely clear that this is not the case.

For me this would be the most serious and important issue in the whole of the academic world, but as I’m in danger of becoming a troll I’ll attempt to stop banging on about it here.

There are also broadly pragmatic reasons for encouraging greater diversity in certain respects: I’m more than happy to appropriate diverse philosophical viewpoints from a variety of traditions if they’ll help advance my particular research agenda. So, Kerry McKenzie and I have advocated this ‘toolbox’ approach to so-called ‘apriori’ or non-naturalistic metaphysics which treats the latter as a set of potential tools that the philosopher of science/physics can appropriate for her own nefarious purposes (I used to call it ‘the Viking approach’ but that was deemed rather insensitive). And I think this approach can be extended to non-‘Anglo-American’ philosophical traditions.

Here”s a bad example: Capra’s Tao of Physics (Capra once gave a talk in the dept where I was a postgrad; it was embarrassing.) Here’s a better one: London and Bauer’s response to the measurement problem in QM is typically seen as a presentation of the standard ‘consciousness collapses the wave function’ solution and it was so regarded by Putnam who then critically hammered it. Except London started off as a philosophy student in the Husserlian phenomenological tradition, and what he meant by ‘consciousness’ was quite different from Putnam thought he meant. And that raises the possibility of an entirely different proposal but to develop it you’re going to have to get to serious grips with that particular tradition … (ax grinding over)

Of course it can be objected that I am just appropriating philosophical artefacts for any own ends without due consideration of their cultural context (in the grand tradition of British imperialism). Thats true but I don’t think I need to engage in such considerations to make use of these devices (and if I did, where would such consideration end?). And, of course, this is not to deny that there may be other reasons for encouraging greater diversity, again in certain respects (including improving student recruitment – another pragmatic reason).

Having said all that, I also agree with David Wallace. And I doubt that changing names will have any impact on anything whatsoever.

cheers,

Steven

I don’t know which is more disturbing, On the one hand, there is the fact that I received such a hostile reaction for expressing a concern regarding arguments in non-Western philosophy (and only a spectacularly uncharitable reading of my post would take it as “pontificating” when I confessed my ignorance and asked to be corrected by people who knew better). Or maybe it is more disturbing that I received such a hostile reaction for expressing a concern that, based on the posts here, seems justified. It sounds like there are arguments in, say, Chinese philosophy, but that a significant proportion of what goes as “Chinese philosophy” makes little use of argument, including Confucius, whose absence in Western philosophy departments is given by the original article as an example of what is missing. How big the “diversity problem” is regarding Chinese philosophy, then, is going to depend on what is being rightly overlooked and what is being wrongly overlooked. Diversifying for the sake of collecting new arguments may well be justified, but let’s be clear on what this diversity is supposed to capture and what it isn’t. We could make science less “white” by expanding our notion of what counts as science, but we should keep on eye on what science should be.

I apologize if mine is the hostile response to which Hey Nonny Mouse refers. I don’t usually participate in blog conversations of this sort because they so amplify my alienation from the wider field and render me impatient. Not the commenter’s fault, to be sure, and I expect I released some accumulated temper in my earlier remarks. But now that I’m in this conversation let me just explain how these sorts of conversations read to me and how, it seems to me, they repeat endlessly. On my most cynical days, I think we can dispense with any further conversations about including non-western traditions. For here are all the conversations:

Someone proposes expanding the field to better incorporate non-western sources.

The conversation will then go on with the following ingredients, mixed in various proportions and orders:

a) someone(s) will simultaneously profess not to know non-western sources and express skepticism that the sources are philosophical;

b) someone(s) will offer argument that – hey! – there are some good things out there and here’s a list of some (which, if ensuing future iterations of nearly identical blog conversations are indication, most everyone will ignore);

c) someone(s) will make claims along the lines of “I once read something in that area and it wasn’t very good” and thereby ostensibly settle the matter for us all;

d) someone(s) will offer incredibly condescending remarks purporting to explain what philosophy is (once and for all! in a blog comment!) and, well, there it is, non-western stuff just, alas, doesn’t fit (not that there’s anything wrong with that!);

e) someone(s) will offer patronizing paths toward normality for the deviant folk studying non-western traditions (e.g., if you could just justify yourselves to us with reference to forms and styles we find completely familiar and won’t overtax us, then you could belong too);

f) someone(s) will claim as unexceptional fact that philosophy isn’t western at all but cosmopolitan, universal, objective, physics-like (pick your own wildly ambitious poison here) and so must for its own good purity eschew things bearing cultural labels;

g) someone(s) will play precision-mongerer and take issue with some minutiae in any proposed expansion and insist that change ought stop dead in its tracks till we sort out this tiny detail;

h) someone(s) will point out that as mere mortals with limited budgets, we can’t be expected to do everything (or presumably even anything where non-western traditions are concerned);

i) the entire conversation will expire under the weight of all of this until next time someone resurrects it like, zombie-like, to “live” all over again in our consideration with all of the points a)-h) to be repeated.

What you won’t find in any of these conversations: reasonable intellectual humility, anything like the inveterate curiosity philosophy purportedly cultivates, or responsiveness to epistemic authority and expertise. I submit the following question: Who would be best positioned to *know* or authoritatively make recommendations about what, if any, non-western philosophy should be included in US departments? Answer: Trained philosophers who have expertise in the non-western philosophical domains under consideration. Now since this is, after all, philosophy, I don’t expect complete deference to authority but even a modicum of intellectual humility, curiosity, and respect for epistemic authority would be a nice change. Put more plainly, Bryan Van Norden and Jay Garfield are *philosophers* and *experts* in Chinese and Buddhist traditions (respectively) and think there’s something worth incorporating here. Their compatriots with relevant training do too. I do wish all the folks on this thread trying to *school* all these folks would at least pause to recognize that you are interacting with *other philosophers who in fact know more that is salient than you do.* If we saw even a little of that, maybe the zombie would finally die. Until then, I will make a bingo card of the above and await the next installment of the zombie chronicles.

I believe the hostile response to which Hey Nonny Mouse is referring to is mine. Indeed, my language was a bit inflammatory, and for that I apologize. On reflection, such language probably has as little place in a discussion amongst philosophers as do the types of responses that Amy lists here, for the reasons she gives regarding epistemic humility. It is to such responses here and on other blogs that I was reacting.

j) someone(s) will offer glib and cynical caricatures of far more nuanced views and sincere questions in an attempt to convince everyone that the issue, which is in fact difficult and worth discussing, is so clear-cut that only the most arrogant, parochial philosophers would engage in any way but to express agreement.

I think that many philosophers do not include non-Anglo-American voices in their teaching mainly due to ignorance, rather than committed narrow-mindedness or malice. The American Association of Philosophy Teachers is working against the ignorance. Our twenty-first biennial workshop-conference, this summer in Michigan, has two aspects which some readers might find interesting:

We have a theme for the conference, inclusive pedagogies, to which many of our workshops and three plenary sessions will speak. Selected papers will be published in a special issue of our AAPT Studies in Pedagogy. (Unfortunately, submissions are now closed.)

One of the plenary sessions is a panel, organized by the Society for Teaching Comparative Philosophy, which, “will explore some of the basic theoretical background useful for non-specialists who are interested in including non-Western and comparative resources in their classrooms, followed by some example modules that we as comparativists use in our own classes at both the introductory and upper levels.”

http://philosophyteachers.org/conference/

The AAPT is a collegial community of engaged teacher-scholars, dedicated to sharing ideas, experiences, and advice about teaching philosophy, and to the support and encouragement of both new and experienced philosophy teachers.

russell marcus

Chair, Program Committee

American Association of Philosophy Teachers

The discussion is getting rather heated, which seems a good thing for such an important topic. There are are all sorts of complications here, and perhaps nobody can be criticised too harshly for not knowing the literature unless they also criticise it. The marketing of Asian philosophy could be better.

The ‘phrase ‘Asian philosophy’ can only make sense to a tourist. Anyone who is doing philosophy is doing the same philosophy, albeit they may be doing it well or badly. For Asian philosophy there is what is true and what is false. Lao Tsu is an Asian who is a philosopher. If his philosophy is correct then it is correct everywhere.

The idea that universities should teach more Asian philosophy is, therefore, evidence that not enough is taught. It would be Huxley’s ‘Perennial’ philosophy, the philosophy which is not just Asian but on which all mystical philosophies normalise, that is not studied.

It has to be said that this other tradition of philosophy has not explained itself well in terms that can be understood without a considerable amount of study. There is a good reason for this but the fact remains, and the effect is not unpredictable. It would certainly be unfair to criticise the man on in the street for knowing nothing about it, or even a genius working in computers or economics.

In philosophy the situation is different. Here the difficulty of the topic might be expected to be a professional challenge. That so few people even read the .literature is bound to to seem astonishing to to someone who does, and even at times infuriating, as we see. There is a need for an intermediate literature that bridges the gap between the two world-view.

Jay Garfield’s book on Nagarjuna would be a contribution but is too complex for this reader. I’m not sure it’s any easier than Nagarjuna himself. There are simpler books. It seems to me that the whole of Asian philosophy would have to be contained and explained in any book that explains Nagarjuna correctly.

The topics are difficult and a lot of work remains to be done before it could become fair to criticise scholars generally where they do not know about this stuff. Philosophers as a sub-set can be criticised, but perhaps only since the internet came along. Schopenhauer had to read the Baghavad Gita in Latin!

The crucial point for me would be that if university philosophers do not study ‘Asian’ philosophy then this intermediate (In the sense of ‘mediating’ and not ‘mid-level’) literature will not be written. This is difficult stuff and not everyone would be able to deal it. The Buddha tells us not to bother but a scholar cannot take this approach. So the curriculum would be a vital and important issue, and one about which some people may get a bit hot under the collar. We wouldn’t have to believe that this other philosophy is any good, just know what it is. Otherwise it might be correct and we would not know it, which is surely not a position in which any philosopher would be content to remain. It is surely very odd that the worst-known philosophy in so many departments is the oldest one.