We Are Not Human Individuals

Unbeknownst to many people, our emotions, cognition, behavior, and mental health are influenced by a large number of entities that reside in our bodies while pursuing their own interests, which need not coincide with ours. Such selfish entities include microbes, viruses, foreign human cells, and imprinted genes regulated by viruslike elements. This article provides a broad overview, aimed at a wide readership, of the consequences of our coexistence with these entities. Its aim is to show that we are not unitary individuals in control of ourselves but rather “holobionts” or superorganisms—meant here as collections of human and nonhuman elements that are to varying degrees integrated and, in an incessant struggle, jointly define who we are.

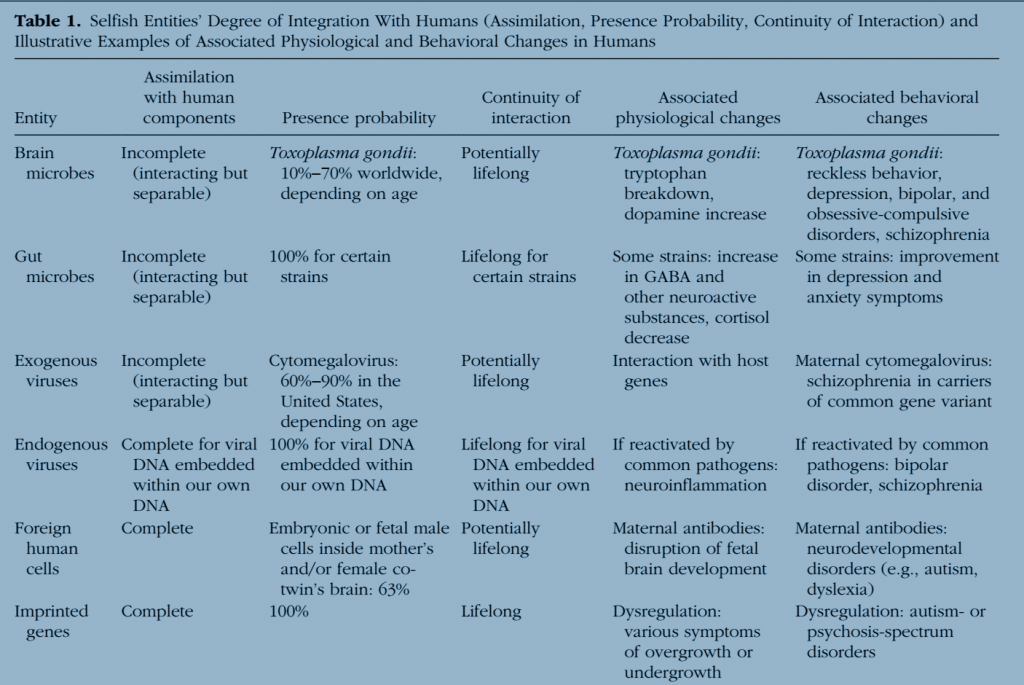

That is the first paragraph of “Humans as Superorganisms: How Microbes, Viruses, Imprinted Genes, and Other Selfish Entities Shape Our Behavior” by Peter Kramer and Paola Bressan (Padua). The article is a useful summary of various findings about nonhuman biological entities that exist in humans and affect our thoughts and behavior. The following table, from the article, provides some examples:

There are lots of interesting nuggets in the article (e.g., a possible explanation for this), but what comes through is just how much nonhuman activity there is going on in us. The authors take the prevalence of the phenomenon to support their conclusion about our nature:

Whereas our cohabitation with one or another of them may not pose a strong challenge to the commonly shared assumption that humans are unitary individuals, the presence of a large number and wide variety of such entities—and the power they have on us—renders this assumption untenable. We are not organisms but superorganisms, and understanding our behavior ultimately requires an understanding of the network of selfish entities that inhabit our body and actively interact with it. It is time to change the very concept we have of ourselves and to realize that one human individual is neither just human nor just one individual.

Does the evidence warrant changing “the very concept we have of ourselves”? What would that mean?

On one view, we haven’t learned anything fundamentally different about humans—we’ve just filled in the details about what we’re made of and what kinds of things influence us (and as it turns out, more of those influences are inside the “skin bag” than we might have thought). On the other hand, these findings do seem to interfere with a fairly common view about human nature and prospects for rational agency that informs a lot of philosophy. Are these philosophically interesting findings? At the very least, that is a philosophically interesting question.

(via Nadira Faber, who posted about this article at Practical Ethics)

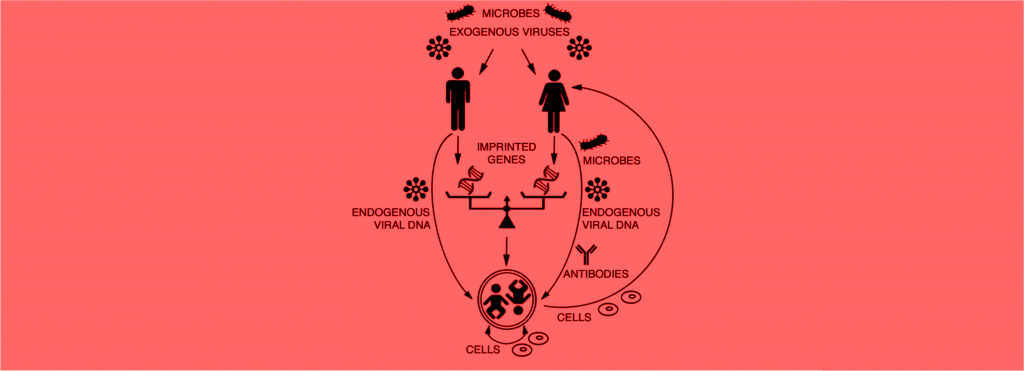

(image: Figure 1 from “Humans as Superorganisms” by Peter Kramer & Paola Bressan, with technical assistance by Nino Trainito)

Instead of saying that we are not human individuals, can’t we just say that a human individual is comprised of lot’s of different kinds of entities? The whole human/non-human distinction comes apart, for if you removed all the non-human parts of a human it would be dead.

is it philosophically interesting? deleuze built a lot of his career on it (and not just the part with guattari). so did simondon. the concept of a unitary self is just a fiction added post-factum to give coherence to the chaos that “we” otherwise “are”. so the real question is : is this philosophically interesting to those who haven’t yet read deleuze, and if so, will they now begin to read him seriously ?

was deleuze talking about symbiotic organisms, parasites etc.? is that his argument against the ‘pre-factum’ existence of a unitary self? if not, how does that go?

“the concept of a unitary self is just a fiction added post-factum to give coherence to the chaos that “we” otherwise “are”. so the real question is : is this philosophically interesting to those who haven’t yet read deleuze, and if so, will they now begin to read him seriously ?”

What an incredibly original thinker Deleuze was! After all, it’s not like Hume or Nietzsche put forth the idea that a unitary self is a delusion before him. Certainly no one founded a major world religion based on the idea in India 2500 years ago.

Since he wrote books on Hume and Nietzsche, I think your point is wasted on Deleuze.

The point was directed at felonius screwtape, who seemed to be tacitly suggesting that the idea originated with Deleuze. (Just so we’re clear.)

We are not individual humans following our own will if we are influenced by ideas circulating in our culture. Such as the idea that our behaviours can be determined by biological entities within our bodies

Our behaviors are not “determined,” they are the result of many factors interacting in complex ways, including the influence of nonhuman organisms incorporated into our bodies as well as the nonhuman organisms upon which we depend for the energy that runs all of our cellular processes, i.e., the photosynthetic activities of green plants that trap the energy of the sun and make it usable by animal life–and yes, I think that fact is philosophically interesting, or at least that one is not only scientifically but also philosophically ignorant if unaware of this dependence of human life upon “other” life. Another set of factors arises out of our being “superorganisms” in a different sense, individual organisms that function largely as members of larger groupings and are strongly affected by the beliefs and propensities of all the other human beings making up these social groupings, a fact that is also philosophically important to understand and come to terms with, since so much of our social world is created in this way, and could be altered in needed ways if our ability to change it is brought increasingly into consciousness. And a third set of factors, perhaps not yet well understood, are the neuropsychological events underlying agency, the reality of human choice.

I’d like to know more about what the authors mean by “organism” and what it is to be one before substantively weighing in, but my initial impression of this article is that there is nothing here that undermines my belief that I am a unitary organism. Sure, I may share the same space with lots of critters that influence how I behave, but that is also true of the city I live in–doesn’t make me any less of an individual human organism. Anyway, thanks for posting; I now have this marked in my “to read” pile.

Chart’s missing thetans.

And midichlorians.

I think what is meant by “organism” is a complex biological system with a self-sustaining form of organization, one that maintains its form and function within a narrow band of parameters for as long as it is alive, against the forces of entropy tending to break it down. (I think one needs to approach such entities with a certain kind of holistic perception to fully appreciate them–our heavily entrenched reductionistic stance has made them hard to “see” in the recent history of western philosophy.) How all this works is incompletely understood by science, although ways of intervening into such systems and making certain sorts of changes–the full effects of which we are unable to predict or “control” at the present time–have been developed by the technological branch of that human endeavor we know as science. The phenomenon of Life–instantiated not just in human life but in all life found on this planet–is surely worthy of philosophical investigation, especially at this time in our species’ evolutionary history, when our collective human activities, if continued along the same trajectory they are currently following, are putting the continued existence of all extant lifeforms on Earth in considerable doubt. Whether or not the Earth itself should be considered an “organism” in its own right is controversial, but biological organisms–plant, animal, fungal, protist–are, in my view, sufficiently well demarcated as to qualify as “individuals,” though such unitary individuals may also come together to function as, on the one hand, more and less well integrated superorganismal entities, e.g., in the human case, nation-states, corporations, political and religious groupings, soccer teams, etc, and on the other, ecosystems, or in the human case (recognizing our self-awareness and ability to choose the trajectories of our collective action) social-ecological systems.

So what exactly do the authors think is beknowest or bethinkest by many people? That every atom in our body is a well-oiled machine all working towards a common goal? We all know that’s true of the New England Patriots but I don’t think many people regarded individuals that way in the first place. So there’s probably no need to junk “individual” just yet.

I think Alfred Tauber’s work on how this kind of evidence changes our idea of Immunology is a great way to start getting a grip biologically and philosophically on this kind of problem: http://ndpr.nd.edu/news/31627-the-limits-of-the-self-immunology-and-biological-identity/

A host of causes, both environmental and genetic, contribute to our development. However, I’m not entirely clear how this claim supports the conclusion that we are not individuals.