The Distant Future of Philosophy

Philosophy, like any human activity, is influenced by the circumstances in which it takes place. Technological, scientific, economic, political, cultural, social, etc., factors influence how philosophy is conducted and at least some of which questions philosophers take up. Philosophy is also the product of its history, with the philosophical agenda of each era strongly influenced by the choices, ideas, arguments, and questions of earlier philosophers.

Since the circumstances and history of philosophy will be different in the future, it is reasonable to ask whether philosophy will be different in the future, and if so, how.

Will there be philosophy in 100 or 1000 or 10,000 years? If so, what will its methods be? What questions (or kinds of questions) will philosophers take up? What will philosophy’s institutions be? And should our thoughts about the distant future of philosophy influence how we do and think of philosophy today? What do you think?

Here’s a different, more abstract, and possibly less helpful way to think about philosophy’s future. Call it the Pessimistic Dilemma of philosophy’s future:

Assume there is a finite number of fundamental philosophical questions. In the distant future, such questions either will or will not be satisfactorily answered or dismissed (perhaps to other disciplines or domains of inquiry). If such questions have been satisfactorily answered or dismissed, then philosophy as a fundamental problem-solving enterprise will have no further future. If such questions have not been satisfactorily answered or dismissed, then we will have (even more) very strong inductive evidence that they cannot be answered or dismissed, in which case we should give up on trying to answer them, and so philosophy as a fundamental problem-solving enterprise will have no further future.

In short, if philosophy makes progress or if it doesn’t, its future doesn’t look so good.

(The dilemma rests on a couple of assumptions that may be false. One of those assumptions, stated at the start, is that there is a finite number of fundamental philosophical questions. Another is that philosophy is a “problem-solving enterprise.” That may sound like a weird assumption, given how little consensus there is on which, if any, philosophical problems have been solved. But nonetheless, I do believe it is the understanding of philosophy that a lot of “analytic” philosophers have. We take ourselves to be providing answers to questions about what really is the case, and not merely engaging in an activity of self-expression.)

Of course, the first horn of the dilemma needn’t be understood as bad for philosophy. If philosophers do answer fundamental philosophical questions successfully, such that we needn’t investigate them anymore, then that could count as a triumph—but a triumphant end, nonetheless.

Does the end of philosophy strike you as bad? I think philosophers tend to have a view that philosophy is something that we—that cultures—should always have. But such a view, in conjunction with there being a finite number of fundamental philosophical questions, puts pressure on the conception of philosophy as an enterprise the aim of which is to answer such questions.

Another possibility is that, even after the fundamental questions have been answered, there would remain plenty of interesting and fertile non-fundamental philosophical questions for philosophers to take up, and so philosophy would not be over. It would just be very different.

I would love to know what form future philosophy will have. I suspect that some combination of economic pressure and political orthodoxy will result in the disappearance of philosophy departments as we know them. After all, we don’t make money and we keep questioning everything. I don’t know how many philosophical questions will be “satisfactorily answered” in the next hundred of thousand years. It is disheartening how little philosophers can agree on after two and a half thousand years or so and it would not be surprising to find that we agree on even less after another thousand. Yet the questions philosophers deal with are so important, I can’t see humans just giving up on them if there is even a chance of answering them. If there are people in a thousand years, they will ask themselves “how should I live?” and will be forced to make some kind of decision on the matter. I believe that philosophy is inescapable.

I love this question. I have little idea how to answer it, but I very much doubt that the answer depends on how many “problems” there are in philosophy or whether such problems will ever be “exhausted” or “solved”. It seems to me that as long as there are incarnate humans (at least ones that are biologically similar to us now), there will be humans pondering fundamental questions.

But here’s what I wonder:

1. Is philosophy essentially tied to writing? If so, what if there comes a point when writing ceases to exist?

2. Will colleges & universities exist in 1000 or 10,000 years? If not, what form could/would philosophy take?

3. Does philosophy require some degree (however modest) of economic or political or cultural stability in order to exist? If so, would future cataclysmic events (climatological, military, etc.) lead to the destruction of philosophy?

Hi Dan, I’m indeed into the future of philosophy as much as you and every single person who left at least a comment under this significant text. As the writer said above, is there finite questions to ask or do we all have countless questions to ask about the universe and existence? On top of that, who are we going to direct our questionings and our theories to, philosophy is not a discipline that leads its stuff in departments or bureaus? Philosophers and thinker have been questioning life and death since the sedentary life started and the first cities established; (so we get that philosophy is pretty much related to architecture) is the questions that should ask by philosophers superseded by those who studies on science or creating stuffs on science? I really wish to strike up a conversation on that topic.

This is a very interesting post. What do you think about the idea that philosophy can be a part of yogic practice? On this view, the practice of philosophy is not just about answering questions, but also about perfecting one aspect of the nature (namely, the mind). A mind that has been ‘tuned’ by philosophical practice might be a better instrument for self-expression and understanding (e.g. by helping with clarity of thought), though the process of understanding may not be limited to traditionally ‘philosophical’ methods.

I wonder how it might be different if we substitute “philosophy” with “science”. E.g.: Suppose there is a finite number of fundamental scientific questions … (indeed, scientists, or at least physicists, in late 19th century believed that almost all the fundamental questions had been settled by Newtonian mechanics. Suppose, counterfactually, they were right about it. Then…)

Philosophy has already ended several times (e.g., Hegel, Wittgenstein…). Yet, here we are.

The radical ahistoricism of this question and its underlying assumptions is unfortunate, even if unsurprising.

@anon female grad student

How is the question ahistorical? This is the first sentence of the post: “Philosophy, like any human activity, is influenced by the circumstances in which it takes place.” Or am I missing something here?

Some replies:

Dan: to answer your questions – (1) No, philosophy isn’t essentially tied to writing (see, e.g., Socrates). (2) All I can say is that they certainly will not exist in their current form. (3) Yes, I think.

Komal: I accept that some people find philosophy to be a kind of intellectual self-improvement. Some people find philosophy therapeutic even (I don’t: I usually find it to be some combination of fun and disturbing). Maybe these are possibilities for the future of philosophy, but they are rather different from what a lot of philosophers today think philosophy is up to (the problem-solving model).

L: I thought about how the dilemma would work if we substituted in, say, physics for philosophy. I think most would argue that the second horn would not apply, and that the “dismissed to other disciplines” part of the first horn also would not apply.

anon female grad: could elaborate on what you mean by “the radical ahistoricism of the question,” and/or suggest an alternative way of framing the question?

Some interesting research has been done in moral and political philosophy related to the points you raise in the first two paragraphs:

http://fqp.luiss.it/category/numero/2014-4-2/

One wouldn’t count it as a bad thing if a science solved all its problems. It would be a “triumphant end, but an end nevertheless”. Endings are not necessarily bad, are they?

But Justin (if I may), aren’t you also taking for granted that – let’s put it this way – a worthy question is only one that accepts a definitive answer? Furthermore, I believe we could make the case for the thesis that what we take as «fundamental questions» are also subject to historical and circumstancial influences. If we take the Sciences as an example, that much gets clear. And oh, Science will always need (new) Philosophy! 🙂

Right, Jonathan — that strikes me as another reason science doesn’t fit into the dilemma the way philosophy does (though I do wonder if scientists would take a less sanguine view about science’s end, that they would feel about science what we tend to feel about philosophy).

João – Sort of. I am assuming that the model of philosophy as a problem-solving enterprise takes at least some fundamental philosophical questions to have “definitive” answers (though we may not now know what they are). But I do think my initial remarks put some pressure on the problem-solving model, which makes me uneasy. Also, I agree that what we take as philosophy’s “fundamental questions” are subject to historical and circumstantial influences; but it doesn’t follow from that that philosophy’s fundamental questions are, in fact, subject to historical and circumstantial influences.

Interesting post. Another assumption that the dilemma seems to rely on is that progress made in answering fundamental philosophical questions at one point in time will be easily accessible to future generations. (I suspect what I will go on to say here relates to what ‘anon female grad student’ was getting at with her comment.) And that assumption seems like it can be reasonably questioned. As you mention at the outset, philosophy (like all intellectual activities) is always embedded in a particular social (economic/technological/etc.) context and that can make it difficult for people to access the insights of philosophers from different times/social contexts (and the same problem can arise in interpreting philosophers from the same time but different social/intellectual contexts). And even if we can be sure that we have clearly understood what some philosopher from the past meant when they said such-and-such (no mean feat!) we still face the task of evaluating the relevant idea or argument, which will require us to do more philosophy.

So, from this perspective, even if philosophy is a “problem solving enterprise” and all the fundamental philosophical questions had been successfully answered in one age it could still be the case that people would need to re-make that progress again in the future, thereby, undermining the first horn of the dilemma. And the second horn is also threatened because, from this perspective, the mere fact that we don’t now have a correct answer to a philosophical question is not a good reason to conclude that such an answer wasn’t given by some (known) past philosopher.

One good worry with the line I just tried out is this: why doesn’t the same problem arise for other problem solving enterprises like math or science? The activities of math and science are always embedded in a social context and yet it seems that (barring events like the destruction of libraries) progress in answering mathematical and scientific questions can be passed down through the generations very well. Perhaps if one pushed enough on this worry then one would be forced to give up either the assumption that philosophy is a problem solving exercise or the assumption that the fact that philosophy is always situated in a particular social context is a barrier to communicating philosophical progress across different times/social contexts (and if one just gave up the second assumption then the dilemma would be back in business). I don’t know what to think about any of this stuff in the end but maybe there’s room for a position where we can keep both of these assumptions whilst explaining the asymmetry with maths/science by identifying relevant features of philosophical questions that make their answers harder to communicate across different social contexts (maybe philosophical questions are difficult in a way that is distinctive from the ways in which questions in maths and science are difficult, or maybe philosophical reasoning is more sensitive to ideology and bias or…).

Sorry for being abstruse—with respect to history: the idea that there are timeless fundamental questions is an odd one (although, to be fair, that’s admitted as a presupposition) … think of a (non-triumphalist) Hegelian picture, according to which the most fundamental problems in any given age are going to be determined fully by the “geist” of that age (the culture, underlying ideas, whatever you want to call it). One doesn’t need the strong claim of full determinism; if the fundamental problems to be at least partially constituted by cultural factors, then new cultures -> new fundamental problems. In fact, it would be the “progress” which itself creates new problems.

Relatedly, as cultures change, so does the human condition. If some of the “fundamental questions” of philosophy are about the human condition, then changes in the human condition would be changes in those questions—or at least, in the answers to those questions.

Moreover, I think part of understanding what and who we are is understanding how we got to the present moment. And as the present moment is always changing, that history is always growing and being reinterpreted according to the values and categories of the present moment, which are themselves always in flux. Again, one doesn’t need to be a strong cultural relativist to get behind these claims. I’m a firm believer in timeless truths, but I’m not a believer in timeless expression (or easy translation) of those truths.

Re #1: It’s true that Socrates did not write philosophy himself, but he lived in a culture with writing, including written philosophy (which he presumably read some of). Could someone who lives in a culture devoid of writing–including a hypothetical culture of the future–do philosophy?

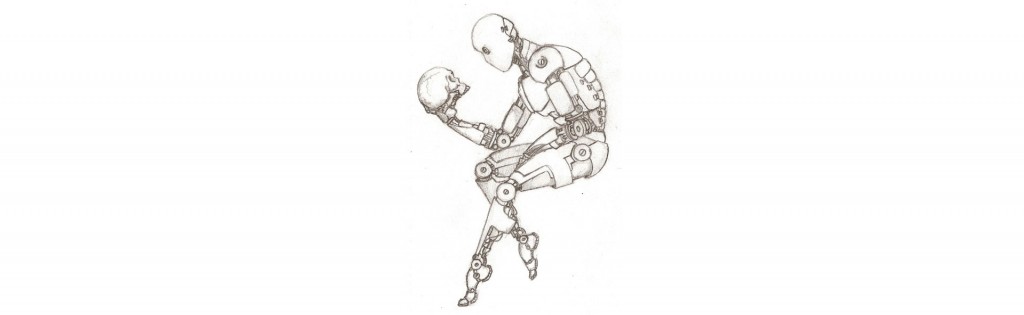

I think when considering 1000 years into the future (and even more if it’s 10000), the question of what sort of being will be doing philosophy (which goes beyond cultural differences) becomes an issue and makes it even harder to try to make predictions about what philosophers will be doing.

For example, maybe AI will by then be so much better at philosophy (and/or physics, math, etc.) than any humans could be, that human philosophers (or physicists, etc. ) could at best study some of the conclusions reached by AI, and the new questions asked by them.

Even if it’s not AI, philosophers could be GM humans much better at science, logic, etc., than we are today, or post-humans resulting from integration between GM humans and computers, etc.

The pessimistic dilemma doesn’t seem like much of a threat. Justin rightly points out how it rests on two assumptions, both of which I find questionable. A third assumption (which may just be just a version of the first) is that it is possible for their *not* to be fundamental philosophical questions with the potential to plague us in any given form of life we might take on. We’re better off understanding philosophy analogously to the way Kuhn understands science: there’s the excellence of “normal” philosophy solving puzzles within paradigms, and then there the philosophical work involved in the breakdown of one paradigm and the transition to another. (A philosopher made this analogy recently but I don’t remember who it was.) A paradigm by definition involves fundamental philosophical problems and, as philosophy is never free of paradigms, we will never run out of fundamental problems.

Many of the preceding comments have focused on the idealized nature of Justin’s assumptions. While I agree that these are idealizations, I’d like to offer an answer that stays within the strictures of those assumptions, if for no other reason than that it might reflect on philosophy’s present self-conception. To me, it seems that a natural response to the dilemma is for future philosophers to abandon what Justin called “fundamental” philosophical questions, and to devote their research efforts to either (a) fundamental non-philosophical questions or (b) non-fundamental philosophical questions. I might treat certain philosophers of science as already doing (a) (and I think that we can read many past philosophers as having done (a), though probably with the understanding (or misunderstanding?) that the questions were philosophical), and most (all?) applied ethicists as already doing (b). Some interesting questions are how Justin’s dilemma would effect philosophical pursuits of (a) and (b), particularly when a fundamental philosophical question is handed off to another discipline, and exactly what makes a question a fundamental/philosophical.

> We take ourselves to be providing answers to questions about what really is the case, and not merely engaging in an activity of self-expression.

Might there not be alternatives to this dichotomy?

I would like to argue that philosophy may, throughout its course, answer a few questions, but that this is neither the purpose nor the main benefit to be derived from the philosophical project. At the same time, I don’t think such a position forces me to accept that philosophers are “merely engaging in an activity of self-expression.” I will list a few of the possibilities, as I see them.

(Side note before we get started: Not that the bias of “merely” behind “self-expression” ought to be seen as necessary, either. I can think of more than one philosopher who was self-confessedly engaging in a project of self-expression, whose works did a great deal to get us closer to the truth.)

1. Can it be that there is something about the way the human mind works that it will ever need the services of philosophers. If every “answer that we find is the basis of a brand-new cliche”, perhaps philosophers can be thought of as the custodians of the furniture of our minds. Always vigilantly struggling against the dust which never takes a day off from accumulating on that furniture?

2. What about those of us who are strong skeptics, not (anti-realists), who affirm that there is truth out there, but that we primates are never going to reach a place where we can satisfyingly claim to own it. We can never get there, but we can always be getting closer. We don’t believe in answers, but we do believe in truth. The formula under which we operate is “Objective truth exists, and the best subjects can do is get closer and closer to expressing it.”

3. Or, here is another alternative: What if we think of the history of philosophy as the progressive accumulation of education. Is it possible to understand a modern philosopher without understanding Nietzsche? Is it possible to understand Nietzsche without understanding Plato? I’m not just saying “understand them” as “realize what they were thinking. I mean “understand them” the in the sense of letting their enlightenment be the furthest development one has made so far on this journey towards truth.

> He that writeth in blood and proverbs doth not want to be read, but learnt by heart.

Perhaps ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny in this regard, and growing up philosophically is like embryonic development. One must pass through the stages. Climb every dangerous crag. There is no helicopter ride to the top, and all minds must make their own journey up this sometimes dangerous trail.

If this is the case, a richer description, defense, or attack on any position will lead to greater enlightenment on every step of this trail (notice, in these mixed metaphors of mine, I haven’t argued that the job of the philosopher is to build something higher than the mountain itself… their job is just to get up there.) The Universe, Richard Feynman once said, is “infinite in all directions.” He meant, by this, not that it goes on forever to the left and to the right, but that it can be “zoomed into” forever at any point. If every step up this mountain can be reworked, rethought, reexamined, denounced, made the central focus, or skipped over, how can this project ever end?

This exercise of philosophy is a personal, erotic, and self-expressive mission to get to the truth. Not a puzzle or set of puzzles which can be “solved” and disregarded. It is an expression of life. As long as life persists, I imagine there will be a need for, and expression of philosophy.

(Postscript, signing off: As always, I’m probably completely wrong about all of this, and I would very much welcome any and all criticisms as they will undoubtedly aid me in my search for the truth.)