Philosophy Journal Hosts Debate on “Jewish Influence” (updates: Article Retracted; Journal Gets New Editor)

Have Jews insinuated themselves into positions of power and influence in politics and culture because they are innately gifted with higher IQs, or is it also because they are ethnocentric and hypocritical networkers good at using non-Jews in their self-serving mission of “transforming America contrary to white interests”? Race science and/or conspiracy theory? This—pardon the editorializing—outrageous question is currently under discussion in the pages of the academic philosophy journal Philosophia.

Welcome to 2022.

January 1st saw the online publication of “The ‘Default Hypothesis’ Fails to Explain Jewish Influence” by Kevin MacDonald, who is described on Wikipedia as an “anti-Semitic conspiracy theorist, white supremacist, and retired professor of evolutionary psychology.” MacDonald’s 32-page article is a response to a piece by Nathan Cofnas, “The Anti-Jewish Narrative,” that Philosophia published last February, and which is one of a series of pieces in which Cofnas critiques McDonald.

Both MacDonald and Cofnas are preoccupied with the question: “Did Jews create liberal multiculturalism to advance their ethnic interests?” (Cofnas, p.1332).

Cofnas’s take on that issue is ultimately based on his claim that “Jews are overrepresented in all intellectual movements and activities that are not overtly anti-Semitic primarily because they have high mean IQs” (Cofnas, p.1331). This is part of his view that there is “legitimate science on race differences” (Cofnas, p. 1332) in regard to intelligence (previously).

Cofnas characterizes MacDonald as claiming that “intelligent, ethnocentric Jews created liberal intellectual and political movements to promote Jewish interests at the expense of gentiles” (Cofnas, pp. 1330-31). MacDonald posits ethnocentric “ethnic networking” (MacDonald, p.2), “Jewish hypocrisy” (p.9), “Jewish activism” (throughout), and efforts to “recruit gentiles as ‘window dressing’ to conceal the extent of Jewish dominance” (p.3) in leftwing organizations, among other things, as elements of the Jewish conspiracy.

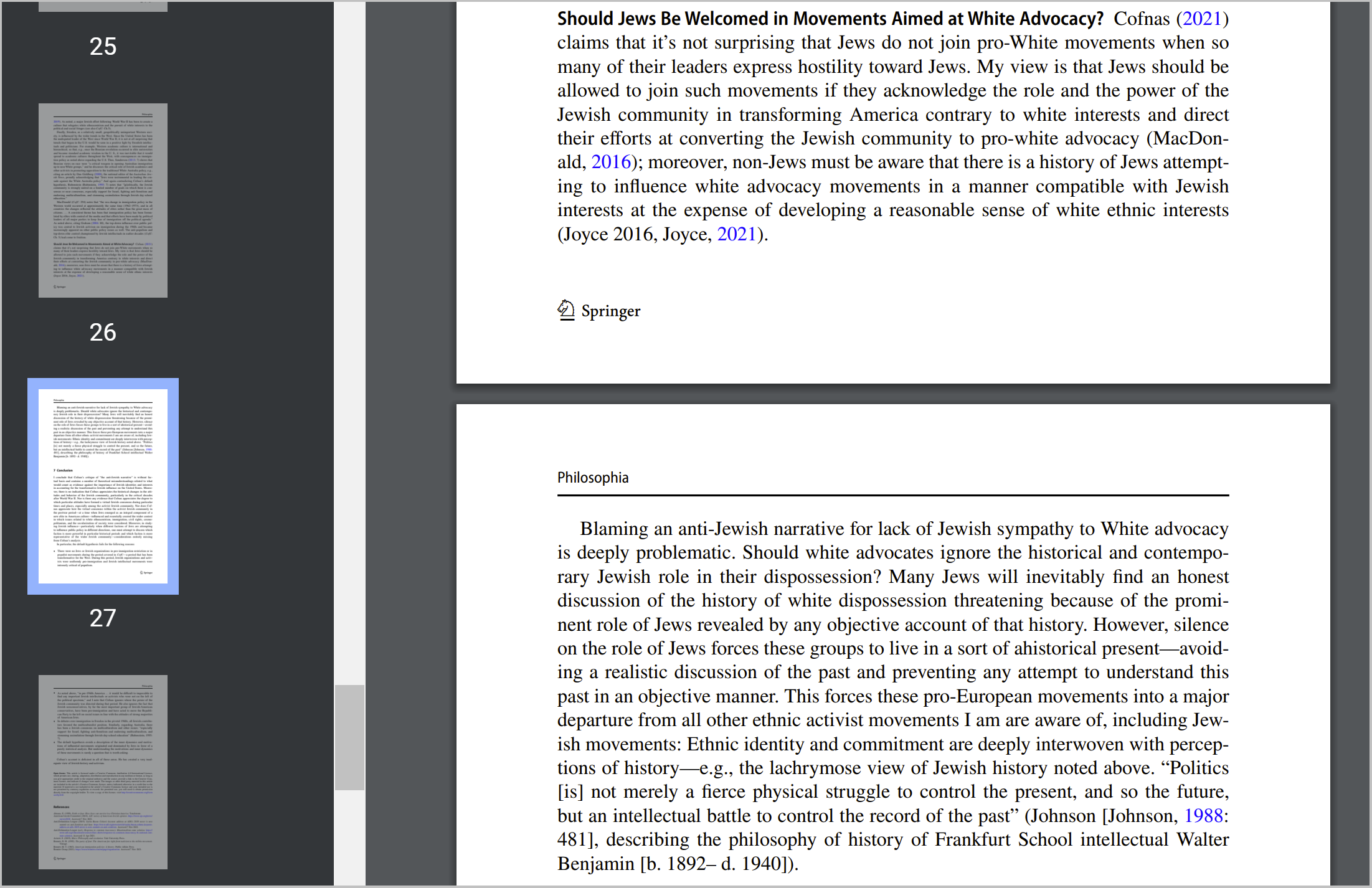

MacDonald also takes up the question of whether Jews should be welcomed by white supremacists. Here is his answer, which I reproduce as a screenshot for those who might otherwise be incredulous that an academic journal published these words:

Did I mention that Philosophia‘s subtitle is “Philosophical Quarterly of Israel“? One might wonder to what extent Cofnas and MacDonald consider the publication of their articles in an Israel-based journal evidence against the presumptions of their debate.

Philosophia is edited by Asa Kasher (Tel Aviv). In response to questions about the publication of these articles, he wrote that the papers were refereed prior to publication, but that it was “a mistake” to publish them, explaining that he was “not aware of the general background of the debate” and that he is “sorry for treating the discussion as an ordinary philosophical debate.” He added that further comments from him may be forthcoming.

Yesterday, Moti Mizrahi (Florida Institute of Technology) who was until last night the associate editor of Philosophia, wrote on Twitter: “I had nothing to do with the publication of this [MacDonald’s] paper in Philosophia. I’ve asked the EiC to reconsider its publication in Philosophia.” Later in the day, he announced his resignation from the journal.

Readers may recall that Philosophia was in the news in 2020 for another paper that was published by “mistake.” Dr. Kasher informs me that he “asked Springer to start a procedure of retracting” that paper, though it remains online.

UPDATE 1 (1/3/22): The first sentence of this post has now been changed to better distinguish between the views of Cofnas and MacDonald.

UPDATE 2 (1/5/22): The following editorial note has been added to webpage for MacDonald’s article:

UPDATE 3 (1/7/22): A person has claimed to be one of the referees for the MacDonald’s paper published in Philosophia, saying that he sent the manuscript back to for revisions a few times, but conveying that he approves of its publication:

Edward Dutton appears to be a self-taught evolutionary psychologist with a PhD in religious studies. According to his Wikipedia entry:

he has written controversial racialist articles for fringe far-right journals such as Mankind Quarterly and OpenPsych, as well as articles for mainstream scientific journals such as Personality and Individual Differences and Intelligence. Some of the books Dutton has authored have been published by Washington Summit Publishers operated by neo-Nazi Richard B. Spencer… Dutton wrote a paper in defense of Kevin MacDonald’s Culture of Critique series, which claims that Jewish people are biologically ethnocentric to the detriment of other groups…

Dutton was previously editor-in-chief of the pseudoscientific journal Mankind Quarterly. He currently sits on their Advisory Board. He is currently an editor of the Radix Journal, founded by American white supremacist Richard B. Spencer.

He does not appear to have any formal graduate training in philosophy, science, sociology, history, or any discipline related to the content of the article he claims to have refereed.

I have written to Philosophia’s editor-in-chief, Asa Kasher, asking whether Dutton was in fact one of the referees, and if so, why. I’ll let you know if I hear back.

(via Lewis Powell, who shared the news in a comment)

UPDATE 4 (1/11/22): A representative of Springer, responding to inquiries, informs me that the Research Integrity Group at Springer Nature is working with the Editor-in-Chief to investigate the concerns and, reiterating the statement placed on the page of MacDonald’s article, “editorial action will be taken as appropriate once investigation of the concerns is complete and all parties have been given an opportunity to respond in full.”

UPDATE 5 (1/13/22): A representative of Springer, responding to an inquiry about a 2020 article that the editor of Philosophia initially said had been published by mistake, writes that “This case was investigated with the support of the Springer Nature Research Integrity Group, which concluded that the peer review process was sufficient, but also noted that the article was submitted under an alias. The editorial note that has been added to the article reflects this.”

UPDATE 6 (6/29/22): “The ‘Default Hypothesis’ Fails to Explain Jewish Influence” by Kevin MacDonald has been retracted, effective June 3rd, 2022. A representative of Springer wrote in to share the retraction notice, which reads:

The Editor-in-Chief has retracted this article. After publication concerns were raised regarding the content in this article and the validity of its arguments. Post-publication peer review concluded that the article does not establish a consistent methodology or document its claims with well-established sources. The article also makes several comparative claims without providing appropriate comparison data. Kevin MacDonald does not agree to this retraction. The online version of this article contains the full text of the retracted article as supplementary information.

Springer has not yet provided any explicit response to concerns about the editor’s selection of Edward Dutton as a referee for the paper (see update 3, above).

UPDATE 7 (7/2/22): In response to inquiries regarding Philosophia editor-in-chief Asa Kasher’s choice of Edward Dutton as a referee for MacDonald’s paper (see update 3, above), a representative of Springer writes:

All concerns have been passed on to the Editor in Chief and we know that he has considered them carefully and is committed to rigorous editorial standards for the journal. We can’t comment on specifics relating to reviewers as we treat this as confidential.

UPDATE 8 (7/29/22): Philosophia will have a new editor-in-chief beginning August 1st, 2022: Mitchell Green, professor of philosophy at the University of Connecticut. Further details about changes to the rest of the journal’s editorial team will be forthcoming.

Note: Comments on this post must be made by people using their real names (first, last) and, as usual, working email addresses (email addresses are not published). Comments are moderated and may take some time to appear. Please consult the comments policy for other commenting requirements and guidance.

It’s better to have these things out in the open and subject to criticism (as in, better for all concerned in the long run), unless you are suggesting that ethnic interests don’t exist or aren’t motives of action that help to shape cultures, or that they can’t be discussed sensibly and frankly.

By way or comparison, we haven’t generally censored discussions of class interests, or gender interests, in academic journals, at least in recent years, though there was a time when they were largely absent at least from Western philosophy journals (prior to the founding of Radical Philosophy in the UK, say).

I’ve seen comparable discussions of “white privilege/supremacy” on the APA blog, for example. See here:

https://blog.apaonline.org/tag/white-supremacy/

Discussions of ‘white privilege/supremacy’ are not remotely the same thing as discussions of ‘ethnic interests’, because the whole point of the former discussions is that the dividing lines involved are socially constructed by the same processes that construct the shared interests. There’s no pre-social entity called ‘white people’ that has a set of interests: the interests of people invested in whiteness are interests in preserving the social structure that counts them as ‘white’ and others as not. In that sense they’re not ethnic interests, and I think it’s precisely right that “ethnic interests don’t exist”.

Doesn’t everyone have an interest in not being unfairly discriminated against?

If everyone has that interest, then in what sense is it an “ethnic interest”?

Everyone has an interest in not being unfairly discriminated against because of their ethnicity.

Luke, can you explain yourself a bit more? I’m not quite sure what you’re arguing. You write “there’s no pre-social entity called ‘white people.'” I hardly see why this matters. Are you arguing that there are no white people because whiteness is socially constructed? Because, if there are white people–even if only via social reification–then, like with ethnicities (which also don’t exist pre-socially), races are meaningful identity categories related to genetic heritage that people place themselves into.

It seems, then, that discussions about white hegemony, and the systems and ideologies designed to maintain it, are very analogous to the discussion of concern here. After all, most discussants who throw around concepts like white hegemony/privilege treat “white people” as a real established category rather than, as you suggest, center their thoughts around the social construction of whiteness itself (though this is indeed a point of focus for some).

In other words, it seems like the distinction you rely on is not a meaningful one for present purposes, and to a certain extent, that the distinction is largely illusory. Or perhaps I’m confused and I just need clarification. . . .

Hi Edward, well for a start I don’t think they’re analogous, because it’s a central element of Cofnas and MacDonald’s arguments to advance *genetic* explanations of group behaviour, in terms of the individual traits that members inherently have. Explanations that appeal to, e.g., white privilege don’t appeal to any such intrinsic traits of white people, but to how they are socially situated and the impact that has.

Thanks Luke. I’m still dubious. A racial taxonomy is socially constructed through the gerrymandering of certain inherent traits into social importance. Sort of like how we “see” constellations in stars randomly scattered in the sky: there may not be a large dipper in the sky, but the stars are indeed there.

Similarly, it’s undeniably the case that when people use the phrase “white privilege” they are overwhelmingly referring to privileges that people have because of inherent traits that correspond to the classification that’s been ascribed social importance (whiteness). That is, race can be socially constructed in an important sense but at once be conceptually founded upon real inherent differences.

All of this is to say: of course claims that white people do X or Y bad thing are generally claims against a group of people characterized by inherent commonalities.

If at one point in time, a group of people wasn’t included among “white people” and then decades later they were, but this wasn’t a byproduct of a change in that group’s “inherent traits” becoming more similar to the rest of “white people”, and instead it was the result of shifting social norms around whether to exclude them when people say “white people supported this candidate in large numbers” or “realtors only sell houses in this neighborhood to white people” (just for example), that might help you understand how you could get a social view which isn’t simply an inherent trait view.

And then the people in that group get the privilege of buying houses in other neighborhoods than before or joining a country club or not seeing a sign that says “No [Xs] or Dogs allowed” on a storefront, without any change in the inherent traits of the group.

I’m not an expert on this stuff so I may have gotten the exact structure of the view wrong.

Anyway, I’m less dubious than you are that we can distinguish hereditarian racial realism from social construction style views.

(I imagine a lot has been written about this and people who are interested could probably read up on it?)

As an American White Jew, this is not only true, but something that comes with an extra edge. My being a Jew makes me a member of an ethnoreligious minority, especially having been born Jewish. My skin is light, and some degree of my genetic ancestry is European, specifically Slavic/Ukrainian in that hinted-at regard when called White (this is not important to being a Jew or not, but for those who still think we’re somehow European colonizers in a post-colonial age, they seem to think it is). This doesn’t matter to White supremacists. If it did, we’d have the ability to walk around without harassment in many places where we are, in actuality, not (completely) safe. And since many (though by no means all) Jews are erasively labeled as White, or rather, to be clear, European, other minorities treat us like we’re part of the top, not at all a minority. This has the extra effect of erasing non-White Jews from the public perception entirely.

Regardless of whether or not race is a real thing or a social construct, it will continue to have extreme detrimental impacts on anyone who is not fully accepted as White, more extreme as one is less and less identified by others as White. It falls on everyone to recognize this, even if one’s “Whiteness” does not seem to bring any genuine benefits or “privileges”, and especially when it comes to acting like any amount of ordinary in-group expectations are grounds to spread conspiratorial assertions.

And of course, I want to take the time to thank Daily Nous for raising attention to issues of antisemitism and upholding professional ethical standards expected of journalists and philosophers.

“Niven’s Law: No cause is so noble that it won’t attract fuggheads.” – Larry Niven

Edward, even if you are right on this point (I’m not convinced), it doesn’t follow that the inherent traits that on your view ultimately ground the characteristics used for sorting people into the socially constructed categories are the same traits that explain the sort of behaviors that interest MacDonald and evidently Cofnas.

Moti, I’m not sure why this matters. It seems here the issue is more simple that some are making it out to be: is it fair to suggest that discussions of things white people do to further their group interests are comparable to discussions about what ethnicities may do to further their group interests? Of course they’re comparable, regardless of the role of social construction in either context. I suspect that some conceptual muddying of the waters is necessary to argue otherwise.

Putting it differently, I’m not comparing the work of MacDonald/Cofnas with discussions of white supremacy and asserting that they’re both in principle doing the exact same thing. I’m simply addressing the more general point raised above by the OP that the academy deems it generally fine to openly discuss group behavior (including groups defined largely by ultimate reference to inherent traits, such as “white people”) as motivated by that group’s interests. This general proposition seems sound.

This, of course, is not to suggest any view on my part that Jews behave in a manner that furthers their collective self-interests. It’s just an elephant in the room that academics do make these claims all the time about men, white people, etc., and we ought not to tie ourselves up in theoretical knots to avoid recognizing this fact.

Edward, I don’t think they are comparable because (among other reasons) the causal stories are so different in the two cases (anti-Semitism vs studies of colonialism or white supremacy). There may be superficial similarities (i.e., in both cases it is claimed that one group has sought dominance).

In any case, I don’t like race-based accounts of social processes, since I think race is less fundamental than other variables.

“Whiteness studies,” to which you (and others, I believe) seem to be objecting risks making it sound as if there is something distinctive about whiteness that gives rise to the kind of violence, domination, exploitation, etc. well-documented by scholars in those areas (and lots of other areas). I think that’s what people often object to about talk of “whiteness.” It’s an unfortunate label, in my view, since the phenomenon it purports to study is only very contingently white (in the racial sense of “white”).

And then it appears sensible to ask “well, why not ask about the Jews, or anyone else, if it’s open season on whites?” I think this is just an unfortunate artifact of an unfortunate label.

Edward, do you really not see the relevant difference between:

“Only green-haired people become doctors because only green-haired people are smart enough to understand medicine”

and

“Only green-haired people become doctors because the ‘Green Hair Rulez’ club burns down the house of any non-green-haired person who studies medicine”

?

Like, yes, in some sense ‘being green-haired’, an inherent trait of green-haired people, is explanatory in both cases, but the explanatory role played is radically different.

Luke, the original post stated this:

“It’s better to have these things out in the open and subject to criticism . . . unless you are suggesting that ethnic interests don’t exist or aren’t motives of action that help to shape cultures . . . . By way or comparison, we haven’t generally censored discussions of class interests, or gender interests . . . . I’ve seen comparable discussions of “white privilege/supremacy” on the APA blog.”

You chimed in rejecting the comparison as not even “remotely” apt. Yet, from my perspective, nothing you’ve written, including in your original response, provides a clear explanation for why the comparison that the OP drew was so off. Your last post, I’m afraid, doesn’t help me much in this regard. Perhaps you can humor me and explicate why you think your green hair alternatives specifically help show that the OP’s comparison was off?

Sorry, but could you be clearer about what you mean by having these conversations “out in the open and subject to criticism?” In the age of social media, pretty much every topic you can think of is being discussed pretty openly. I think we can be close to certain that somewhere on reddit there are debates about whether Jews are using immigration to dispossess the white race, or whatever.

I think the issue here is whether these debates should be happening in academic journals. Part of the interest in academic debates is that they are supposed to go through various filtering processes to make sure that there is some intellectual merit to what they publish, that a reasonable attempt has been made to avoid cranks and conspiracy theorists and work that violates normal principles of reasoned debate. MacDonald’s paper seems to pretty clearly fail to meet those standards.

I’m curious what work “it’s better to have these things said out in the open” is doing here and what guidance that’s supposed to give us.

First, these things *are* said out in the open, so if the claim is meaningful, I suppose it must be saying that it’s better to have them said out in the open *in fairly respectable academic journals* and not just on 4Chan, Twitter, and The Daily Stormer. But why, exactly, is that better? Is it just because we assume that many academics are completely ignorant of things that appear outside academic venues, and it’s better to have academics exposed to them?

Second, does “it’s better to have these things said out in the open” imply that they should be published in journals that supposedly have academic standards? In other words, is the implication that if a view is especially vile, papers expressing that view should be able to make it past standard journal gatekeeping more easily than those expressing less problematic views?

This is an absurd claim, unless you get very clear on what “these things” are and what the boundaries are. Should academic journals dedicate pages to arguing against the David Icke reptile alien theory? Jewish Space lasers? Cofnas argues (extremely unconvincingly to my mind, but at least with specific criteria) the case for engaging with the antisemetic conspiracy theory put forward by MacDonald, but it’s fairly clear that garbage theories are easier to generate than refutations of them, and it’s not at all clear that it’s a good use of anyone’s time to do so (nor that such refutations do anything to dampen enthusiasm for the theories).

Ultimately, then, as I believe Rae Langton has argued (iirc), it is a naive view to simply think the truth will out in such cases, and instead, it seems evident to me that we need to be a bit clearer about what the hell we are doing if we are platforming a crackpot antisemite whose conspiracy theories have already been aggressively disowned by his own former department and academic institution.

Yeah… I think philosophers would be well-served to read Ch. 10 of Linda Lipstadt’s excellent “Denying the Holocaust”. It’s called ‘The Battle for Campus’, and it’s about the AHA’s (American Historical Association) attempts to respond to holocaust deniers in the 1990s.

Their responses included having eminent historians tear them to shreds. Spoiler alert: it made the problem worse.

This is a tangent, but Lewis mentions the fact that MacDonald’s views have been “aggressively disowned by his own former department and academic institution.” I just want to say that I don’t at all like this idea of academic departments, much less entire universities, having official positions on the topics that individual faculty members within those departments and universities write on. My colleague Michael Tooley is famous/infamous for defending the moral innocuousness of infanticide. To many people, this view is just as offensive as anti-Semitism, but I am glad that my department and university never got it in our heads to officially condemn Tooley’s position. (Lewis, I realize that your taking the fact that MacDonald’s views were disowned as evidence that they shouldn’t be discussed in journals does not imply that you disagree with me on this.)

Maybe I’m missing something, but can’t we agree that in general departments should not publicly condemn individual researchers in the department, while acknowledging that it can be justified in rare, extreme cases? I took it this was part of Prof Powell’s point: MacDonald’s department has condemned him in this extremely unusual way, and this kind of condemnation is the sort of thing academics will usually be very reluctant to support.

I am going to do my best to avoid getting drawn into a protracted discussion about this point here. I will make one (lengthy) comment, and then see if I can find a mast to tie myself to.

Let me begin by flagging that the only person who has mentioned the offensiveness of a view in this entire discussion, so far, is you. So, I don’t wish for that non sequitur to get introduced into the discussion and picked up as though anyone else has suggested that the issue is that Philosophia has been gauche in publishing something offensive to the taste or sensibilities of the philosophical community. Maybe that is something people are upset about, but no one has raised that concern, so to my mind it is a red herring.

Second, I misstated, in my comment, by saying “institution”, as it was the academic senate, and not the entirety of the institution (at which I believe he retains emeritus status). This is relevant because academic freedom protections guarantee one certain sorts of non-interference from university administration, and so the question of when it is appropriate for other academics to remark on one’s work is simply distinct. There may be other considerations which make it inappropriate for a department to make a public statement about a faculty member like that, but it would require a different basis that academic freedom (which is why I want to be clear that it was the academic senate and not the administration). If I have a colleague who is a virulent antisemite, and academic freedom ensures that they cannot be terminated for this, I am very glad that I (and presumably the rest of my colleagues) are permitted to say “that person does not speak for us, they are actually doing a very bad job at reasoning about things, that’s why they can only get the antisemitism published on fringe outlets instead of in reputable venues”. And, in the instance where a field has established research methods, and a code of ethics and conduct, and one’s departmental peers say “when it comes to the topic of conspiratorial claims about jews, this person does not follow those methods or that code of ethics and conduct, does not subject their work to peer review, so, sure, for his other work, affiliate him with us all you want, but when it comes to the baseless anti-semitic conspiracy theories, no thanks”

But third and more to the point: while so many people in this thread want to formulate abstract principles, or compare cases (all of which strike me as extraordinarily unhelpful things to do and very much beside the point), the issue that arises for both of these requests is that the devil just really is in the details. So, for example, by following up on what it means when one learns that he is one of the party directors for the American Freedom Party (motto prior to rebranding; but don’t worry, the 2013 rebrand assured folks that: “the values and mission would remain unchanged”), or that he published extensively on VDare, or like, just other stuff he proudly lists among his writings (but which have been swallowed by the sands of time), I can tell “hey, the stuff they said in those whereas clauses holds up, because he was publishing this stuff in non-academic outlets and it really does seem like it’s not meeting the standards of social science research that would ordinarily get published in regular academic outlets.” (The AFP directorship appears to have happened after the disaffiliation, but in terms of whether I am going to pretend not to know what is going on, here, now with this paper, I choose not to play the fool). I’m not personally an expert, or even a novice about academic psychology and its methods, but, given that the stuff he’s pitching is…the same old recycled antisemitic conspiracy theories, just dressed up in new “scientific” terminology, I am happy to bet his ex-colleagues (who were professors of psychology) knew what they were talking about when they decided to make that statement about his work.

This seriously misrepresents my views.

The first sentence of Justin’s post implies that I argue that Jews “transform[ed] America contrary to white interests” because they have high IQs. My argument is that Jews didn’t make such a big difference to the political trajectory of America and the West. More important, my critiques of leftism have never been framed in terms of “white interests.”

This statement implies that the fact that these papers were published in an Israeli journal poses a challenge to “presumptions of [the] debate” that I might accept. But my position is that there is not a Jewish conspiracy.

Why should we openly debate this topic? Why not just call MacDonald some names like “anti-Semite” and leave it at that? I have explained in detail why I think it’s important to engage with him. (See, e.g., section “Do MacDonald’s Theories Merit Scholarly Attention?”) I don’t think it’s right for Justin to insinuate that I have nefarious motives without acknowledging the reasons I have given to undertake this work.

In your comment, Nathan, you write, “my argument is that Jews didn’t make such a big difference to the political trajectory of America and the West.” In the article you link to in your comment, though, you write, “it is an undeniable fact that, in the past few hundred years, Jews have had a disproportionate influence on politics and culture in the Western world, if not the whole world.” Which is it? Perhaps you’ve changed your mind. Or perhaps despite Jews’ influence being “disproportionate” it still “didn’t make such a big difference.”

If it’s the latter, it’s hard to figure out why you say you are taking up the question, “Did Jews create liberal multiculturalism to advance their ethnic interests?” The natural read of this compound question is “What best explains why Jews created liberal multiculturalism?” which you answer with your so-called “default hypothesis”. Why not instead ask the simpler, “did Jews create liberal multiculturalism?” and answer it with “no”?

You write, “my critiques of leftism have never been framed in terms of ‘white interests.'” I’ll take your word on that. You do, though, seek to explain the rise of what you call “extreme forms of radical multiculturalism”—both extreme and radical!—and that sounds like a coded way of talking about threats to so-called “white interests.”

As for my line wondering about the extent to which you and Macdonald consider the publication of your articles in an Israel-based journal as evidence against the presumptions of your debate, that was meant in a tongue-in-cheek way, and applies at that level just as well to your “Jews are genetically smarter” position as it does to MacDonald’s anti-Semitic conspiracy theorizing.

Well…yeah. The fact that Jews had “disproportionate” influence doesn’t mean they “transform[ed] America,” “create[d] liberal multiculturalism,” or even made a “big difference to the political trajectory.” There’s no paradox here.

That is not the “natural read,” especially given that, after posing the question, I immediately give the answer that “the West was on a liberal trajectory with or without Jews, and Jews were not responsible for mass immigration to the US.” This is one of the main points of the paper.

I do not think “sounds like a code[]” is sufficient evidence to make such accusations against me.

Hi Justin and Nathan,

Having read (most of) your paper, Nathan, I disagree with Justin that your agreement with MacDonald on Jewish IQ or disproportionate influence gets to the heart of your agreement with MacDonald, which seems to be Justin’s concern. You (henceforth ‘Cofnas,’ since addressing this post to both you and Justin makes ‘you’ ambiguous) and MacDonald are fighting over the direction “race realism” should take: Cofnas wants to purge the ideology of MacDonald-style anti-Semitic conspiracy theories. According to Cofnas, race realism without the anti-Semitic conspiracy theories is more “genuine,” by which I think you mean empirically sound.

So what is the race realism that Cofnas wants to rehabilitate? I understand it to be the conjunction of two theses. The first is rejection of what Cofnas calls the “mainstream narrative about race,” which he defines as the thesis that “all groups have the same innate

dispositions and potential, and all disparities—at least those favoring whites—are due to past or present racism.” The second tenet of Cofnas’ race realism is that rejection of this “mainstream narrative” is of profound social and political import. He says that “much of our social system is founded on the scientific premise that all groups (if not all individuals) are basically the same…. The long-term success of humanity will depend on our ability to come to terms with reality, including controversial facts about group differences” (1342).

Why think belief in innate racial differences in potential is so important for humanity? Cofnas takes up this question in his “Research on Group Differences in Intelligence: A Defense of Free Inquiry.”

https://www-tandfonline-com.libproxy.txstate.edu/doi/full/10.1080/09515089.2019.1697803

There, he identifies two policy issues that, he claims, bear some connection to beliefs about racial IQ differences: the Head Start program and, quoting Kourany, “that there are differences that might call for the creation of a program to ‘work with the strengths and work on the weaknesses of every [ethnic] group to help make them the very best they can be.’”

How do these issues put the long-term success of the species at risk? The Head Start program costs a few billion a year. Moreover, there’s a mountain of literature on its benefits, all of which Cofnas ignores in favor of cherry-picked findings that support his narrative. Those interested in this research can easily find it. I don’t pretend to be an expert on Head Start and am agnostic on whether it’s beneficial. What’s clear is that Cofnas’ discussion of it is, to put it mildly, incomplete.

What about programs to work with the strengths and weaknesses of different ethnic groups? I don’t know what this means and Cofnas doesn’t offer any concrete details. Interpreting him charitably, it sounds like the idea is that some ethnicities are good at STEM, while others are good at, say, building things with their hands. So we should offer more carpentry training for the benefit of the latter groups. If that’s the idea, the policy issue doesn’t hinge on beliefs about racial IQ differences: Cofnas cites a single study on the benefits of training for different kinds of skills and it doesn’t rely on racial differences. Indeed, tying the policies to controversial beliefs about racial differences is more likely to hinder than help them. Those who truly believe that such education policies are critical to human success would presumably advocate for them differently.

So to sum up: Cofnas thinks acceptance of race realism is needed for the long-term success of the species because (a) it would increase opposition to a relatively small program whose only putative downside (given everything he’s said) is wasting a negligible fraction of US GDP and whose benefits he gives no indication of having studied; and (b) it would increase support for training students in a wider variety of skills–a policy that can be (better) defended independently of race realism.

If these are the benefits of race realism, it’s hard to believe that they’re its real motivation qua political ideology. They’re much too flimsy.

Maybe the most interesting aspect, to me, of Cofnas’ disagreement with MacDonald is his explicit neutrality on whether “Jews should be white nationalists” (1342). This is particularly striking given Cofnas’ blase acknowledgment, in the abstract, that “some” people who reject the “mainstream narrative on race” “gravitate” towards MacDonald’s ideology, i.e., anti-Semitic white nationalism. (“Ho-hum.”) As I discuss in a comment below, MacDonald’s ideology (the Great Replacement Theory/white genocide) is a form of political extremism that has inspired numerous mass shootings, the 1/6 putsch, violence in the streets, and MAGA authoritarianism. Moreover, it retains almost all of these dangers even without its anti-Semitism. Cofnas’ acknowledgment entails, then, that there’s a substantive link between even his race realism and a virulent strand of political extremism. This is one of the most important effects of race realism that Cofnas has posited in either of the two papers I’ve mentioned; certainly, it’s of deadly importance. It’s a bit shocking that one could espouse an ideology, while aware of such a link, when the benefits of doing so are as flimsy as those Cofnas attributes to race realism.

As for why we shouldn’t engage him academically: you have *literally* been a primary party to elevating his non-serious, non-academic anti-Semitic conspiracy theories into more serious academic venues by engaging them as though they merit careful, thoughtful attention and rebuttal. This isn’t a difficult question, and the current situation clearly bears it out, where your response to him appears to have opened the door for his work (which has been roundly rejected by his own former institution, at the level of his department all the way up to the entire academic senate), to gain ground as worthy of serious debate (when it is clearly not).

A few thoughts:

1. Why is this discussion happening in a philosophy journal? The questions here seem largely empirical, and perhaps quite important, but not particularly well suited for philosophical method. Even if there are some ethical upshots, these papers are not obviously framed around ethics, social ontology, etc. This point may also explain why the issue that MacDonald’s paper was supposedly refereed, if it was hard to find qualified readers.

2. MacDonald’s work should never be published in a respectable journal, even if Cofnas is right that MacDonald’s influence among the alt-right, among other reasons, should persuade us to debate MacDonald’s views in print.

3. As a philosopher who’s a Jew, I sometimes reflect on how academic analytic philosophy is, anecdotally, a better place for Jews in America than many humanities departments. This phenomenon seems to be explained at least in part by a sort of conservatism in analytic philosophy; some other humanities disciplines draw more on leftist ideology which sometimes traffics in anti-Semitic rhetoric, especially conflation of Israel with Jews. Although I don’t feel threatened by this article, I’m certainly disappointed (including because I’ve appreciated articles in Philosophia in the past), and I’d be curious for thoughts others have on academic analytic philosophy and Jews.

I’ll add that I’m hopeful about the project of radical philosophy that’s not anti-Semitic.

Are you sure that academic analytic philsophy really contains much “conservatism”? Perhaps it draws less on leftist ideology than other humanties disciples (perhaps because some of that ideology is a product of postmodernism, which in turn is a product of continental philosophy, which is not taken very seriously in analytic philosophy), but that hardly by itself makes it conservative. It may be that analytic philosphy draws less on leftist ideology simply because it is pretty apolitical, not because of any conservatism. Doubltess much work in core areas such a logic, metaphysics and philosophy of language is quite apolitical. It is also possible to be political but not draw on leftist ideology be being, say, moderatly liberal rather than conservative. Moreover, there is a great deal of leftist ideology among some poeple who draw on analytic philosophy and engage with it quite seriously, such as Richard Rorty.

I also doubt that leftist ideology in itself results in bad settings for Jews. Leftist ideology does not have to include anti-Zionism or Anti-Semitism, though it sometimes does.

Thanks, Avi. I think you’re broadly correct. The sense in which academic philosophy has often been conservative is that of not engaging in big-picture social critique, and thereby upholding aspects of society’s status quo. We might point to political philosophy not informed by historical and current racial discrimination, for example. We might also point to to procreative ethics not informed by the experience of women as those gestating and giving birth. Or we might point to gender and racial imbalances in our field. I don’t think that disinterest in certain forms of leftist ideology makes the field conservative, but the factors I have in mind do make the field less likely to be interested in those ideologies. In any case, I agree that leftist ideology need not be anti-Semitic.

I’m interested to see that you think more liberal disciplines would be more hostile to Jews, since so many Jews themselves are liberal (speaking anecdotally, but also the Pew Research Center has also found that, with the exception of Orthodox Jews, they are mostly liberal/democratic). Though I agree with you that anti-zionist, anti-semitic language is common on the left, it doesn’t seem to me that more conservative disciplines (if indeed analytic philosophy is such) would be any better. Most of the people I know whom I would characterize as anti-semites, or who have said antisemitic things around me, are in fact conservatives.

Hi Alexandra, yes, the type of conservatism I’m talking about is very consistent with voting Democratic. Most philosophers are politically on the left, by American standards, as are most American Jews. What makes some disciplines hostile to Jews, from anecdotal evidence I’ve heard, is sorts of thought that are on the fringes of mainstream American political discourse (although becoming more common, often for the good, in my opinion, despite periodic issues with anti-Semitism). The American Democratic party is far from leftist.

I have no wish to defend these paper, but let’s not boundary police philosophy to criticise them. There’s no “philosophical method”; there are many things philosophers do and one of them is to engage heavily with empirical evidence. That’s the principal activity of some (excellent) philosophers. Have a look at specialist journals like “Mind and Language” or “Biology and Philosophy”. They contain many papers that are heavily empirical. Sometimes- rightly in my view – the generalist journals publish work like that.

Hi Neil, thanks. I’m a bit confused by your response, especially by your dismissal of philosophical method. Of course there’s no one philosophical method, or perhaps even a category of philosophical methodology. But there are ways of thinking and writing that are recognized by philosophers as philosophical. More importantly, there are questions that philosophers attempt to answer, and questions that philosophers leave others to answer (or rarely ask). There are certainly topics that philosophers should be talking and thinking about more than they current are, but there are topics that they’re not best suited to tackle.

In the case of Cofnas, a philosopher who also publishes in science journals, the question is why this contribution should be in a philosophy journal. My initial question was an honest one–I’d be happy to understand better why this contribution should be in a philosophy journal. (I’m a grad student working mostly in ancient, and some applied ethics, so I’m not as familiar with philosophy’s borders with cog sci and biology, and the sort of work published in those subdisciplines.)

Lots of things are clearly philosophy. Nothing is definitely not philosophy. Philosophy is completely porous. If philosophers start doing it in their professional capacity, it’s philosophy. More precisely, when a philosopher starts doing something in their professional capacity (writing papers on predictive processing, or on game theory, or producing formal models) that should be seen as a bid: they’re saying “I think this, too, should be philosophy.” If the profession refuses, then the bid failed. If it allows it, then its philosophy. The cases I mentioned are all cases in which we decided “yep, that’s philosophy”.

Nice!

Sent from the all new AOL app for iOS

Neil, I agree that philosophy is an extremely broad discipline that includes empirical reasoning, to the point that I consider science itself to be the branch of philosophy devoted to empirical testing.

However, individual philosophers and journals have boundaries to their expertise and it seems clear to me that neither the Cofnas nor the MacDonald papers were within the scope of their reviewers’ competencies.

Max, I’m disturbed to hear your report of anti-Semitism in academia. I’m aware that anti-Semitism exists on the left, but I’ve not, to my knowledge, encountered it in academia. I was trained as an analytic, but I’ve worked with a lot of continentals, and nobody has ever said anything to me that struck me as anti-Semitic.

Hi Greg, just to clarify, I have no evidence that there are problems in the continental philosophy world. I’ve mainly heard of issues in area studies fields, including ones on the border of humanities, like ethnomusicology. But I have no hard data.

As a Jew, when I read such things I have one main reaction: good, all is working according to the Plan.

I knew it!

I think there is too much hyperventilating in the responses I have seen to this event. The claims should mainly be considered in the context of the actual piece, as was probably done in the blind review process, and only later in a, possibly good, ad hominem way, taking into account the context of the author’s life and other publications, as well as the contexts of its various receptions. Name-calling is not a mature way to approach this. Consider the claims one by one, and the evidence for them. I shouldn’t have to say this. It is what we all teach. So practice what you preach! This comment is not directed to any particular discussant or group, but to the predominant tone of the discussion so far. Sent from the all new AOL app for iOS

Various anti-Semitic conspiracy theories have been circulating for centuries and, of course, many of the claims they make–as oft happens with conspiracy theories–are virtually impossible to disprove, while some can be disproven but only through an incredibly time consuming process that convinces only those who already know the conspiracy theories are trash, while those who believe in the conspiracy theories ignore any counterevidence and move on to new talking points.

Maybe I’m missing your point. But are you suggesting that every time anti-Semitic conspiracy theories pop up, instead of just saying “this is anti-Semitism,” we should waste our time on refutations that will serve no purpose other than to give the anti-Semitism publicity and the appearance of gravitas?

Making an evidential assessment is not the same as proving something false. To prove something false may indeed be more work, and is also (as an aim) an instance of begging the question.

To counter you, has there ever been a thoughtful analysis of anti-Jewish social / political / racial theories? One whose primary telos isn’t the suppression anti-semites?

If so, there is probably no need to rehash. Or if not, pay someone to do it so we have something to point people to.

To display fragility by hiding or suppressing discussion is catnip to the disaffected, apart from being repugnant in itself.

“To counter you, has there ever been a thoughtful analysis of anti-Jewish social / political / racial theories? One whose primary telos isn’t the suppression [of] anti-semites?”

This is a truly shocking pair of questions to read. The answer to the first question is, “Yes, obviously. Just google it. If you want a famous historical exemplar, try Sarte’s “Anti-Semite and Jew.” The second question seems to presuppose that suppressing anti-semitism is bad actually. But it’s… well, it’s not.

I’m pleased to have shocked you Mark. I think that’s a rare thing on the internet; perhaps even more rare with a clean and reflective conscience.

The first question is conditioned by the second. I’m indicating that what I mean by a ‘thoughtful’ analysis is one that doesn’t take the suppression of anti-semites as a primary aim. However, my ignorance here is thorough. This isn’t a problem, because my question’s rhetorical purpose was to set forth salient possible states of affairs, not to illustrate a dearth of such analyses.

So, reducing your criticism to the second question…

It’s not as easy to control what my questions seem as it is to control what my questions intend. Sometimes it’s impossible to cause what they seem and what they intend to align (at least for a certain audience), and I’m afraid this may be such a time.

To answer you more simply, if not less obscurely – it’s harder to walk along a cliff’s edge than to push someone off it.

I suppose you think you’re being clever and erudite, Matthew.

In any event, I’d wager that the majority of work on anti-Semitism doesn’t take as its primary aim suppression but rather understanding. Several people in these comments have repeatedly pointed out that approaching these conspiracy theories as objects of study is perfectly fine. Researchers ask questions like, “What is the rhetorical function of this conspiracy theory?” “What risk factors make certain individuals more prone to accepting such conspiracy theories?” and “How is conspiratorial ideation related to other pathologies such as delusions and dissociative thinking?” The people asking these questions do not have suppression as a primary aim, as you seem to suggest.

It’s clear from your engagement above that you are either completely unaware of this literature or pretending that it doesn’t exist.

From your Twitter (e.g., https://twitter.com/MattCapps/status/1468675477300727816?s=20) endorsement of the Left Behind series, which notoriously trades in anti-Semitic tropes and conspiracy theories, I conclude that your conscience is clean because you don’t have a problem with anti-Semitism.

Having no genuine competencies, to think of myself as clever and erudite is my only consolation.

You on the other hand, are genuinely erudite: knowing more about my biography than I do. I haven’t yet clicked your link, but I don’t doubt your acumen for research.

In fact, I imagine that even the most sober attempts at understanding in the literature (of which I am indeed ignorant) pale by comparison to your keen insights of me.

In the study of anti-semites your work is surely exemplary, and none the worse for appearing in an informal medium.

Now I know where to send my paper on hematology ethics in the matzos industry.

Just to clarify: If it was still December 31 in Michigan when this article dropped, is it eligible for this year’s Philosophers’ Annual, or next year’s?

Wouldn’t it make more sense to do it based on the Jewish calendar?

As an ethnic Jew myself, I have personal reasons for not liking it that a number of people believe in a big Jewish conspiracy. I can understand the feeling that we should stop McDonald’s views from being published *or even critically discussed* in an academic journal.

But it’s far from obvious to me that preventing people from reading *or even critically discussing* McDonald’s views in academic journals is the best solution to the problem. That doesn’t follow from the premise that it would be better if far fewer people took McDonald’s views seriously.

Some questions:

1. Does anyone actually think that, if we police enough discussion fora in the ways one can in a non-totalitarian society, and throw out anyone who raises a Jewish conspiracy theory, we’ll eventually get to the point where we’ve stopped all the Jewish conspiracy discussions? Why wouldn’t the conspiracy theorists just move to other forums, or create them, where they can have such conversations away from the would-be censors? And wouldn’t those forums be apt to be especially bad?

2. People who peddle conspiracy theories love to say, “Here’s what they don’t want you to hear about.” Everyone wants to get the inside scoop on things, and this plays into that. When conspiracy theorists can point to clear evidence that mainstream fora block readers from even seeing a case for the theory, it seems to make the conspiracy theory much more popular. Does anyone have good evidence for thinking that this doesn’t give more fuel to the conspiracy theorists, overall?

3. It’s true that many academics would not normally run across cases for Jewish conspiracy theories, and that publishing McDonald’s piece seems to expose many more academics to them. But is there good grounds for thinking that academics would be apt to be persuaded of Jewish conspiracy theories by reading such an article, especially in a publication that also provides a rebuttal in the very same issue, as here? Consider all the academics you’ve met.

4. Considering the contempt that conspiracy theorists tend to have for academic research, how much *extra* credibility would McDonald’s readers attribute to him on learning that his article was published, with a rebuttal, in a scholarly journal?

5. If there’s no plausible hope of shutting down discussion of conspiracy theories, would it be better for those discussions to occur *entirely* in places where critics will often be unable to respond to the arguments and evidence, and indeed where critics will seldom venture?

6. McDonald’s views are not the only ones that people have said should not be aired and discussed in academic or other publications. If editors stand to have their reputations damaged, perhaps in a very public forum, for publishing things some people think they should not have, it will be prudent for editors to err on the side of caution and avoid letting through anything controversial, except for things that parrot the party line in cases where there is strong and heartfelt agreement among academics on some otherwise divisive issues. This is apt to lead quite quickly to an echo chamber within academic culture, and even more so in an environment wherein nearly every topic can be politicized. The result tends to be a fierce consensus among academics that outsiders will immediately recognize as groupthink even when insiders tend not to notice it. Outsiders will therefore, it seems, be more apt to turn to alternative publications and discussion fora in search of balance. Mightn’t this be at least as serious a gateway to conspiracy theories as the alternative one all this seems meant to avoid?

Justin, when you say ‘But it’s far from obvious to me that preventing people from reading *or even critically discussing* McDonald’s views in academic journals is the best solution to the problem’ do you mean to be criticizing people calling for retraction after it is published, or just people who think it shouldn’t have been published in the first place? If the latter, as someone else has already pointed out upthread, surely journals don’t have an obligation to publish every stupid conspiracy theory some people somewhere believe, regardless of whether any decent evidence can be martialed for it. (I’m inclined to agree that retraction would be bad, mostly because it will, as you say, be cited as precedent when people call for less worthless work that they don’t like for political reasons to be retracted, I don’t think it’ll undo any harms from publication, and it’ll give McDonald the chance to play martyr.)

I don’t know, David. It wasn’t my aim to criticize anyone, so much as to point out that a seemingly important set of considerations don’t appear to have been addressed. But I agree with much that you say.

Justin K., the way I see it, there’s a huge difference between discussing a conspiracy theory as an object of study, as scholars who work on them do, on the one hand, and engaging with them “from the inside”, as it were, as this current issue in Philosophia does. You’ve made a case that perhaps doing the latter has some benefits, and maybe it does (I’m not convinced the benefits outweigh the costs). But there is another consideration, which for me is decisive: engaging substantively with anti-semitic conspiracy theories is akin to swimming in a sewer–it just defiles the people who do it.

Just look at the excerpt Justin W. screenshotted. One claim there is that Jews should be “allowed” in white supremacist movements only if they (we) acknowledge the pernicious role we’ve played in setting back White interests.

How did this make it through the editorial process? Putting the mechanics aside: is this a serious academic claim that merits the attention of philosophers, qua philosophers? Is there any philosophical value whatsoever in pointing out that the question of whether Jews should be allowed in white supremacist movements is…misguided?

As my father used to say, when you see a pile of dog shit, it’s almost always better to avoid stepping in it. The case for stepping in it has to be very strong. Do you really think there is a good argument for stepping in it in this case? It’s an absolute embarrassment for the journal and for the profession.

(To be clear, I remain agnostic on the question of retraction.)

Hi, Moti.

Like you, I have a hard time seeing how the discussion of whether Jews should be allowed into white identity movement is relevant. I would have thought (long ago perhaps) that questions of who should or shouldn’t be welcomed into identity groups undertaking social activism had no place in academic inquiry, since academics qua academics are employed in truth-seeking rather than political organization. I have been appalled for a couple of decades now at how normal many academics seem to find it that that boundary line is routinely crossed, more in certain disciplines and subdisciplines than others. I would be very glad to see all of that bundled up and thrown out of academia, and I think there are principled reasons for doing that.

That still leaves us with the general question: should academics be free, qua academics, to propose or dispute causal accounts of the prominence of this or that ethnic group within certain fields? It seems to me that the answer to that question is yes, since among other things it will be useful to have a grasp of the dialectic in case a significant number of people (almost certainly non-academics) start propounding a false account to their advantage. And in order to have a grasp of that dialectic, we need to see how it plays out. I agree that there are also reasons against allowing it to play out in an academic journal, but I haven’t yet seen why those other reasons are weightier.

You raise a prudential question about the risks of stepping in dog waste. For the prudential reasons you give, and the precarious state of existence involved in plying one’s trade in the academy nowadays, many academics will avoid taking such questions on. To me, that’s a reason for being particularly grateful to scholars like Cofnas who respond to the likes of McDonald despite this.

Should an academic journal allow issues like this to be discussed (minus the question of who gets to join a white identity group)? I think you present a good _prudential_ argument that they should not. But none of the questions I asked question that prudential answer. I’m more interested in the broader consequences.

People should be free to ask any questions they wish to ask. The question here is whether academic journals should provide a venue for them to do so in all cases, for all questions.

My view is that they should not. McDonald-style work is unworthy of serious academic interest. This doesn’t mean that there would be no value in someone showing why this is so in some venue, perhaps even a prestigious venue. But academically, philosophically, the question of Jewish membership in white supremacist activism is bereft of interest.

I have read interesting articles on Jewish intelligence (higher IQ scores) Jewish success in the US, in various cultural institutions, and so on. None were written by adherents of scientific racism; none promoted white identitarianism; none held Jews responsible for degrading “white culture” or the inheritance of “the West.” None were written by authors who, according to Wikipedia, have elsewhere argued that Nazism was a rational response to Jewish corruption of white value.

This is the stuff of the Nazi sewer.

Thank you for the thoughtful reply, Moti.

You say that people should be free to discuss such things in other fora. I’m glad we agree on that.

I might also ultimately agree with your closing comment that “this is the stuff of the Nazi sewer.” and that it therefore has no place being discussed and debated in a serious philosophical journal — you might persuade me quite easily, in fact — but only if you make clear what fair criterion or method you propose to distinguish the acceptable from the unacceptable.

I’ll give you a reason for my being hesitant on this point: I once, like you, thought there were clear and objective criteria in place that ruled such stuff out as proper academic philosophy. But I have seen a number of philosophical talks, articles and books over the years that violate such norms as ‘No sloppy, negative generalizations about any ethnic groups’, ‘No grand theories of one ethnic group’s domination over others or control of the world’s resources, buttressed by cherry-picked data’.

I’m no right winger, but I don’t understand why some of the views I just mentioned have been winked at and even openly applauded at academic philosophy talks or in the journals. Is it because some of this racialized material is associated with the far right (unacceptable) and some is associated with the far left (acceptable)? That can’t be a fair standard for an objective academic enterprise, much as I hate what the far right has to say. Or is there some clear criterion that doesn’t leave it up to the personal and socially-influenced judgment of editors? If so, what is that criterion, roughly?

It’s completely fine with me if the criterion also rules out the large-scale racial theorizing and antagonizing of the identitarian right as well as the identitarian left: if you say that it all should get chucked out of the journals and into the sewer where it belongs, I’ll raise a glass to you in approval. But a double standard is a recipe for bad philosophical practice, and violates some of the fundamental norms of the discipline, as I hope you’ll agree.

Sorry, are you saying we can’t retract the Nazi article unless we set up a relatively mechanical procedure for deciding whether or not to retract any paper addressing issues of racial identity–because otherwise we would be acting unfair to the Nazis?

I don’t think he’s worried about being unfair to Nazis. I think he’s worried about our being unfair to people in the future whom we designate as being on the same level as Nazis, but who are, as a matter of fact, not.

I get the sense Kalef is imagining two systems of norms:

System 1: whatever passes peer review is not subject to retraction (unless it’s fraudulent).

System 2: views that are incredibly offensive may be subject to retraction, even if they pass the peer review process.

No system is perfect: the problem with System 1 is that it will allow some anti-semitic tripe through. The problem with System 2 is that it’s vulnerable to people labeling views that they don’t like, but which are defensible, as incredibly offensive, in the hopes of getting them retracted.

I get the sense that Kalef favors system 1 because he’s afraid that system 2 will be too easily gamed. I don’t know what I think. But I may have Kalef’s views wrong.

I will note that, other than the place where Heathwood introduced the notion of offensiveness below (which I already flagged) this is now the only place where “offensiveness” has been mentioned. So I think if that is the concern, it has not been made clear, and it does not accurately capture any criticisms of the paper that have been offered.

I’d appreciate if, when people describe what is being objected to about the paper, they do not replace the objections that have been levied with different objections that are frequently dismissed as not worthy of attending to, such as “people find it offensive”. The issue with publishing baseless, unfounded antisemitic conspiracy theories is not that people are offended by them. It is the other things that have been said against publishing them, in the other comments.

Lewis, first of all, my apologies, I accidentally reported your comment when I meant to click like. Mea Culpa. Hopefully this doesn’t result in your banning. Or mine.

And yes, I just wanted to add that my position is:

(1) Academic journals should only publish papers of academic value.

(2) MacDonald’s paper is without academic value.

(3) 1+2 probably justify retraction, and definitely justify taking steps to improve peer review in future.

See, this is the problem.

At one extreme, there is the policy of never clicking anything. At the other, there is indiscriminate clicking. Adopting the latter policy is bound to result in occasional misclicking REPORT, and getting innocent people banned; the former would mean you can never LIKE anything. Of course you could adopt an intermediate policy, but then you have to have an objective criterion for deciding when to click. I am doubtful that there is such a criterion.

I fear you are sliding down some… metaphor I can’t recall, and are in grave danger of ending up in a… something really bad I can’t think of at the moment.

This is why I click when it’s obvious that clicking is the thing to do, and I set aside settling on a criterion until I encounter difficult cases.

LOL. Nicely done.

First, no one proposed system 2. Second, he explicitly says that maybe certain topics should be off limits, but that that needs to be applied equally to people on the right and the left, otherwise we are being unfair.

Why is your stance on the Macdonald paper conditioned on whether Moti can successfully overcome whatever grievances you have about other, unrelated publications on “the left”?

Either this paper is baseless, conspiratorial nonsense or it isn’t. If it is the former, and you agree, then say so, and maybe bring up the other papers you think do the same thing as also making the same definitively flawed mistakes.

If you disagree, have the courage of your convictions and defend the paper as worthy of publication and meriting our attention (at which point I will know not to take you seriously).

But you have been framing your measured/tepid defense of this article in a half-hearted/half-measured way, as though that is reasonable, and all it really does is allow you to conversationally, defend the publication of the anti-Semitic conspiracy theory without any clear demarcation of your stance. Your stance isn’t/shouldn’t be contingent on Moti’s Gorin’s.

Right now we aren’t talking about some other unspecified papers you are invoking to both-sides this thing. Do you think this paper *as it is written* deserves to be taken seriously by academics? Ought it be retracted? If you can’t take stances on those issues without vaguely gesturing at your dislike of leftist trends in publications, why not?

In his initial reply to Moti Gorin, Justin Kalef indicated that his personal view of this paper’s merits is irrelevant. In his view, “academics should be free, qua academics, to propose or dispute causal accounts of the prominence of this or that ethnic group within certain fields.” The debate needs to proceed, he believes, “since among other things it will be useful to have a grasp of the dialectic in case a significant number of people (almost certainly non-academics) start propounding a false account to their advantage.”

It is difficult for him to hold the opposite view in a principled way. You might see why if in the first quotation above, you replace ‘ethnic’ with ‘gender’. Given his publicly known beliefs about gender issues in the profession, if the paper were about the prominence of men in philosophy being the result of their bad behavior toward women, he could not hold that the paper should not be published, or that there’s no need for debate.

Derek and Lewis: I’m not saying the things you seem to think I’m saying. I don’t have any conviction that this or that paper is worthy of publication (though I suspect that some of the cases that they are not so worthy have been made reflexively and without consideration of consequences or principle). Whether McDonald’s paper or Cofnas’s paper should be retracted is a matter I don’t have a fixed opinion on, though it seems to me that others are making that case very confidently without, as far as I can see, sorting out the principles and implications first. That’s what prompted me to comment.

What approach do I prefer for such things? Since you seem curious, I’ll state that more clearly. The most important thing by far is that the rules and principles need to be objective and applied fairly, not on the basis of which side happens to have political support in the contingent historical circumstances in which they are offered. It is almost equally important that standards be _seen_ to be applied fairly.

Then comes what to me is a secondary question: should generalizations on the basis of race, ethnicity, sex, gender, etc. be permitted to be made, and prominently made, in academic papers? I would be quite happy to agree that the answer should be no to that across the board. But if such a policy is repeatedly violated by people who routinely publish critical (and often very broad-brush) generalizations about one ethnicity, supplemented with cherry-picked facts, then we are already in the sewer Moti mentions. In that case, we lose our basis for prohibiting the discussion of papers that do the same thing with a different ethnicity in the cross-hairs.

That is honestly where I stand with all this. I began years ago with the understanding that none of this business belonged in academic journals and talks and classrooms. Then I saw that many others violated what I took to be the rule, and that nobody did anything about it, so I concluded that the principles people follow in academia are not what I took them to be or wanted them to be. Now I’m wondering whether there really are any principles, or whether academia as a whole is even pretending that there are principles, or whether most academics even care. I’d be much happier to find that I’m mistaken about the principles that are applied, or to be convinced that the principles are different from what I think they should be, than I would to learn that, indeed, I’m an outlier for caring about whether we act in a principled manner.

Let’s start by distinguishing pedagogical contexts from research contexts, since you are lumping them together. If you are teaching a class, and during class discussion, a student introduces certain baseless/odious proposals into the conversation, you might wind up having certain responsibilities to engage with the student’s comments, and take them seriously, due to a) the fact that they have been presented to the whole class, b) your pastoral/pedagogical responsibilities towards that student, c) your pastoral/pedagogical responsibilities towards the other students, etc. We can then have a conversation about what the best ways are to engage with those proposals in class while making sure you uphold your responsibilities as an educator, your responsibility not to spread pernicious ideas to the students in the classroom, and so on.

Separately, but still in the classroom/teaching context, there are considerations about how to structure course content, because, as educators, and outside of certain areas/topics like (some) logic courses, we are in a discipline where attention needs to be paid to the fact that many questions aren’t settled, and so, proper pedagogy often/usually involves teaching conflicting views on a debate. The fact that I think a given position in a debate in a contemporary moral problems class is false is not, in and of itself, a sufficient reason not to teach a paper advocating it. At the same time, when choosing papers to teach, or positions to consider in a class, the driving consideration is pedagogical value. How does it serve the purposes of the course? If these are principles that satisfy you, great! They are helpful to me here, because, I don’t (currently) teach any courses whose pedagogical goals are served by reading papers that advance antisemitic conspiracy theories. I can think of some courses whose goals are advanced that way, but the simplest case would be a course about the nature of anti-semitism (where the paper is being treated as an object of study, not an argument to be engaged with).

The actual thing we are discussing here, however, concerns the context of research and publication, not pedagogy. So the questions are whether this antisemitic nonsense should have been published in a serious journal (answer: obviously no), and whether it should be retracted (answer: obviously yes). Now, peer review is a large scale bureaucratic process. Failures are bound to happen. Good articles will be mistakenly rejected, bad articles will make it into print. The issue, however, is that this article very, very obviously falls well below the established academic standards for a reputable journal, due to it advancing a long discredited, pernicious conspiracy theory that is lacking in academic and evidential merit.

Now, this is not merely my judgment of it. MacDonald’s own former department and in fact, the academic senate for CSU Long Beach have both formally and publicly disassociated themselves from his anti-semitic and conspiricist work, over a decade ago. Note that, among the concerns raised by the department (who had him present his work at a forum for the department, before formally disassociating themselves from it), they reference methodological/conceptual concerns, concerns with whether he was following the (other) APA’s ethical principles and code of conduct, and “It was also noted that many of these writings have appeared in other media rather than in psychological journals that require peer review and rigorous scientific and psychological methodology.”

Anyway, I do think it is very weird that you are bringing left-wing vs. right-wing into this. I’d have hoped that everyone within the pale, as it were, agreed with the principle “journals ought not publish baseless pernicious conspiracy theories, and if they do, they should retract them” but, I am left to infer, from your remarks, that you think there are a plethora of left-wing baseless pernicious conspiracy theories that get publishes all the time, and so you’d like us to make space for this one on some sort of goose/gander basis?

You may have noticed that my tone has gotten slightly snippier, and that is because you ended your comment with the extremely insulting suggestion that you are some rare outlier in terms of having principles out here in the world of philosophy (perhaps all of academia?), though you have yet to even attempt to substantiate the absurd false equivalence that our journals are rife with anything comparable to this antisemitic tripe. So, please rest assured that I am dialing back my tone quite a bit, because for you to act holier than thou while offering lengthy, specious, and sophistical defenses of this paper is a bit hard to take.

Since I never wrote a defense of the paper, I never wrote a “lengthy, specious, and sophistical one.” I already explained that I wasn’t defending the paper.

Justin,

You said that it wouldn’t be fair to retract MacDonald’s paper without first establishing rules that would lead to retracting certain papers on the left side of the political spectrum. To whom, exactly, would it be unfair?

I’m largely in agreement with Moti and Lewis. I think we need principles for hard cases or gray areas. But it seems like everyone agrees that this particular paper is both intellectually without merit and racist. Any principles we formulate to explain why the paper should be retracted are going to be more controversial than our judgments about the case itself. Maybe there are trickier cases that do call for principles. But this one seems pretty straightforward.

As for why I am so confident it should be retracted–it’s because no one in this entire conversation has defended the paper. No one seems to think that it adds value to the academic debate. Everyone seems to agree that it is in fact racist. Convergence of expert opinion seems like pretty good evidence to me.

I think some degree of trust in our colleagues and in our profession on these matters is warranted. And if it isn’t–and you really seem to be suggesting that it isn’t–then maybe this discipline is a mistake.

Justin,

I don’t have a theory or principle that can distinguish between the sewage and the non-sewage. But I don’t think we always need one. Whatever principle we end up with, we already know that some will fall on the sewage side of the line, some on the other side. Same with plenty of things, e.g., pornography. We do not always need some tidy theory of the nature of pornography to know that a particular case clearly counts as pornography or that some other case does not. I think McDonald’s work, academically or philosophically speaking, is equivalent to horse necrophilia, pornographically speaking.

Particular outlets need to make judgments with the help of peer review. Occasionally, there will be mistakes, and something like McDonald’s work will slip through. People respond critically, there is discussion and debate, some editors resign or not, and so on. That’s how these things will get resolved, not by appeal to some principle to which everyone has pledged allegiance.

As I’m sure you can appreciate, it’s difficult for me to respond to your claims about left-wing equivalents, or possible equivalents, without specific examples. Are there philosophy papers out there arguing for Louis Farrakhan-style “white devil” positions, where white people are claimed to have some essential properties in virtue of which they are evil, corrupt, whatever? Not that I’m aware of. That’s the kind of paper we’d need to see to have a fair comparison.

To me, it seems that a Jewish conspiracy theory is false and, if widely accepted, apt to lead to bad things whether or not it entails that we Jews have “essential properties in virtue of which they are evil, corrupt, whatever.”