“Biting the Bullet”: A Note on Style from Caspar Hare

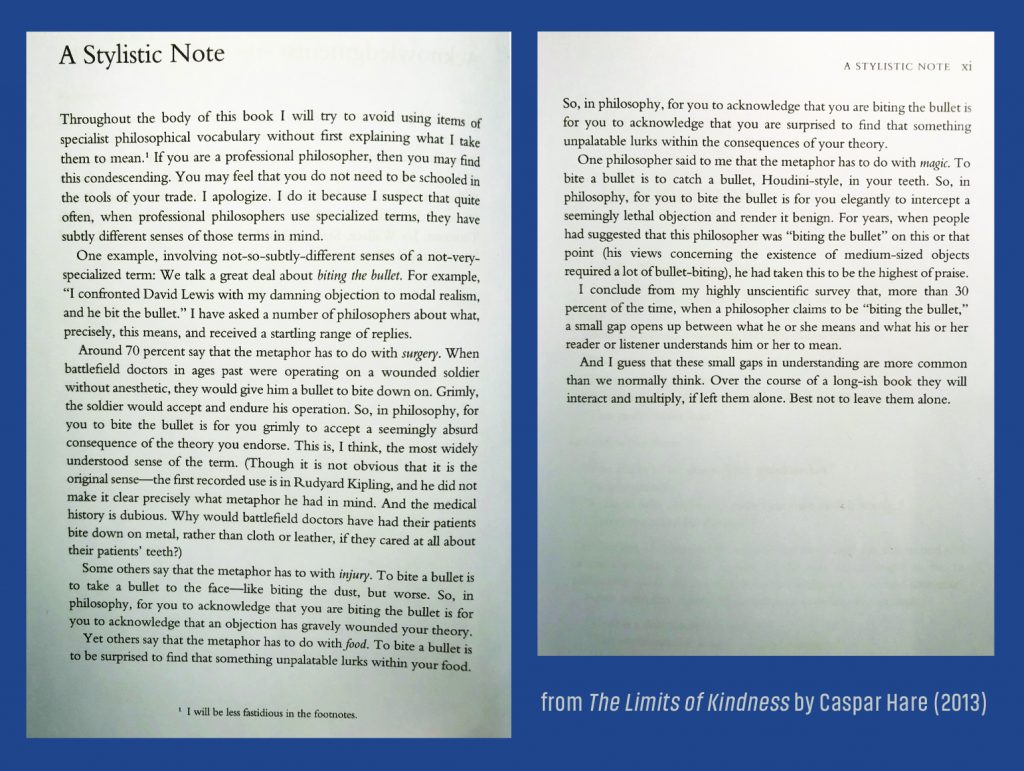

In his 2013 book, The Limits of Kindness, Caspar Hare (MIT) includes a brief “stylistic note” that gets across an important lesson for academic writers: don’t overestimate the familiarity of your readers with specialist terminology—even when the intended readers are others in your discipline.

Such terminology may be unusual words or purpose-built neologisms, but may also just be a technical way of using or putting together ordinary words. You may want to avoid using them or be sure to explain them when you do.

Professor Hare’s example is “biting the bullet”:

I agree that “these small gaps in understanding are more common than we normally think.” Your examples of other terms or phrases subject to such gaps would be welcome.

Almost anything in Latin except maybe et cetera. Most of my students misuse “i.e.” and “e.g.” and have never heard of “viz.” much less “mutatis mutandis.” Even “prima facie” is worth avoiding, not least because some use it to mean “pro tanto.”

It has long seemed to me that many philosophers (esp., but not exclusively, in the areas of logic and analytic metaphysics and such) use the phrase “just in case” in a technical sense quite sharply divergent from its ordinary usage. As far as I can tell, it often seems that specialists use it to mean something like “if and only if” or “only in the case that”; whereas in conversation outside the discipline, as far as i can tell, it almost never has this sense (and instead means something more like “in preparation for the eventuality,” or as one dictionary has it, “as a provision against something happening or being true”). I still find the specialist usage (eg in SEP articles) quite jarring when I encounter it, even though I’ve been familiar with it for years.

As an international PhD student and a nonnative speaker, I hope philosophers can in general use less idioms, slangs, and culturally specific examples. Examples that come to my mind include “drive it home”, “beat around the bush”, “barking up the wrong tree”, examples about sesame street, and examples using baseball rules. They create exactly “small gaps in understanding”. I realize that it’s hard for native speakers to recognize them though.

I wish to second International above. I once had to go to the dictionary after my advisor told me in a meeting that a solution I offered to some problem was rather “flat footed”. I didn’t want to appear stupid so I didn’t ask.

(I really wish the “reply” function could be made to work again. I realize that this site seems to be groaning under its own weight, but if that can be fixed, it would help a lot.)

It “Another International Grad” – you should not feel hesitation to ask such things. Even moving to Australia from the US, I encounter expressions all the time that I don’t understand at all. It will, even in the short term, make you look less intelligent if you don’t ask.

On the main topic, not an example from philosophy, but from my other field, law – sometimes, when discussing whether a witness is credible or not, a court will say that a witness was “incredible”. The first time I encountered that I was briefly very puzzled. Isn’t it normally good if something is incredible? If I said, “X was an incredible witness the other day”, most people would take this to mean, I think, that X was a very above average witness. But here it’s used to mean “not credible.” Of course, grammatically that’s fine, but I still find it jarring, so I warn my students to look for it, and advise them to use “not credible” or “non-credible” instead themselves, so as to avoid confusion with no loss in meaning.

I’m glad to see this caveat, especially regarding culture-specific idioms. I want to add that, in addition to avoiding obscurity, it might also incidentally benefit originality in philosophical writing. While I totally understand that idioms can expedite understanding between scholars (albeit largely within cultures), the use of “bite the bullet,” “cut any ice,” “doing all the work,” etc., over and over again, across an otherwise diverse range of literatures, just starts to feel… uninspired, I guess. It doesn’t help that many of the idioms are outdated in the broader culture (who *sincerely* and *non-academically* says “that doesn’t cut any ice,” nowadays?). That said, this is a purely aesthetic and flimsy and borderline unserious criticism, and I’m just as guilty of using (and later cringing at my use of) these idioms. Still, I sometimes wonder whether this contributes to a popular conception of academic philosophy as insular and boring. Our idioms just aren’t cutting any ice; let’s add some creative zest!

Put as much Latin in as possible. Too bad if they don’t get it. Use a dictionary.

What a great topic, and I really appreciate Prof. Hare’s example and analysis. I wonder, though, if this is this more an issue of *metaphor* generally than technical jargon? (Granted that, as in Hare’s example, sometimes technical jargon can be metaphor-laden.) Even if it is, of course, that’s no reason why writers still shouldn’t be cognizant of the possible parochialism of their own metaphors. At any rate, another example that comes to mind is “strawman”. Philosophers I’ve spoken with treat it as a reference to: (a) a scarecrow, i.e. something that is designed to spook casual onlookers but doesn’t hold up to closer scrutiny; (b) an effigy, i.e. something that “goes up in flames” or is defeated easily, even if it fools no one; or (c) a practice target for military exercises, i.e. something that neither masquerades as something stronger or more real, nor “fights back,” but can nevertheless be useful for instruction. As with Hare’s example, the slight differences in connotation between these three can make for divergences in the interpretation and assessment of larger points and arguments.

I don’t think any terms should be avoided merely because they could introduce confusion. I think the best option is what Hare has done: explain terms that are liable to introduce confusion, if there are no other ways for the reader to get an explanation (e.g. a dictionary).

Pace “You rather than Me’s” concerns about culturally specific terms, I like it when these pop up and I don’t understand them (so long as I can find an explanation somewhere) because this is how I learn things. I shudder to think how cramped and bare my world view would be had I grown up only reading things that were written in a bland cosmopolitan style stripped of any local flavor that might have confused me for a moment.

Perhaps one might argue that philosophy, unlike most other things, ought to be written for clarity only and thus all stylistic choices which do not serve clarity should be foregone. But, again, I am only suggesting that these terms be explained when they are used (like Hare does) or that they have explanations available elsewhere. Philosophy books don’t have to be Pynchon novels.

Perhaps one might argue that reading philosophy is typically hard enough for students without having to open up a dictionary or whatever to figure out what’s going on. Fair enough. But I think reading philosophy is typically boring enough for students without stripping it of any local color. Imagine trying rewrite Plato’s dialogues in order to strip out all the confusing references to Greek culture. There’s something to be gained there, for sure, but so much to be lost, too. Better instead to footnote those things.

For those who wish to help their students with this sort of thing, my website has a glossary of common terms in philosophy. I link my students to the glossary to help them out with their readings.

Re: Daniel Weltman,

I agree–I didn’t wish to imply that all philosophical writing should be as simple as possible, repetitive, constant, etc. In fact, I was specifically saying that the *overuse* of certain idioms is *itself* what makes some philosophical writing monotonous. I want *more* creativity in language, not less. To illustrate the point, and how it diverges from your reading of my comment: I would gladly welcome the introduction of newer idioms, novel turns of phrase, and so on, rather than reliance on the familiar!

(Addendum: that includes creative forms of writing whose understanding requires some investigation.)

Trying to figure out what “bite the bullet” meant led me to read Smart, which gave me (and gives me) great pleasure. There’s a lot to be said for being forced to look things up and finding your way, just as there’s a lot to be said for scanning library shelves, learning languages, etc.

Kevin DeLapp asks whether this is more an issue of metaphor than technical jargon. That question raises some subtle issues. I think it is often difficult in philosophy to distinguish literalness from figurativeness. (I’m assuming, defeasibly, that technical jargon is designed with the ambition of literalness.) And even if distinguishable, it is difficult to purge one’s technical vocabulary of the figurative or to keep the figurative from informing one’s use of the technical. (“[Nearby, distant] possible world,” “ground,” “set,” and “logical consequence” are a few examples that quickly come to mind, but that’s only because I’m bothered when those who make a show of being rigorous lean heavily on these terms.)

One thing I find odd about Hare’s note is that he reports asking various philosopher’s what ‘biting the bullet’ *means*. But he seems to really be asking about its *etymology*. There are a lot of metaphors one can understand without having a clue about their etymology. Examples for me include ‘squashing beef’ and ‘burying the lede’.

This observation doesn’t take away from Hare’s more general point that one ought to make oneself understandable. Though I tend to side with Garrett and Weltman here regarding the use of metaphors and such.

Re: perplexed

I had that thought as well but then remembered Wittgenstein’s observation that one way of understanding the meaning of a word is to ask after the explanation of it’s meaning. That is, by offering an etymology of the idiom those surveyed are explaining what they take the idiom to mean. Of course the etymology might have nothing to do with the meaning of the idiom but if everyone reckons it does then the explanation will also be an explanation of what they take the meaning to be.

I agree with Animal Symbolicum about the fuzzy line between technical jargon and metaphor. A few years ago, I started to try to avoid metaphors unless I specifically acknowledged them as metaphors. (I see this as a matter of accessibility. As some others here have noted, metaphors are more likely to create small gaps in understanding in those who are non-native users of the language or less familiar with the particular cultural diet of the author.) It didn’t take long to realize how difficult this is to do when writing on contemporary analytic metaphysics. I do think metaphors play an ineliminable role in introducing technical concepts. But they are too often used as crutches that, eventually and ironically, detract from clearer thinking. (Yes, those metaphors were intentional.)

To add another to the list: “x is baked-into y”. This one seems to be growing in popularity! It sometimes means something like “x is presupposed by y”, other times it means something like “x is accounted for in y”, and yet other times means something like “x is an eliminable part of y”.

Peter makes a good point about metaphors. Idioms are often (not always) metaphorical, but they tend to be more precise in meaning than non-idiomatic metaphorical language (like “baked into”, “bear the weight of”, “take aim at”, etc.). You can look up idioms in a dictionary, just as you can look up latin phrases and abbreviations. The fact that some people misunderstand them does not mean that they are imprecise, just that your audience is more ignorant or lazier than you suppose them to be. Metaphorical language, on the other hand, can imply the laziness of the author. It should supplement precise explanation, not substitute for it. In analytic philosophy in particular, we are seeing an increase in metaphorical language that is a substitute for precise explanation or definition. This is a bad thing. Such language makes a person *feel like* they understand, because now they have a mental image, but their understanding is not at all advanced (What does it mean for one proposition to be “baked into” another? It’s unclear, as Peter points out, and in a way that cannot be resolved by a dictionary).

I just want to register disagreement with those saying that the use of metaphor is a problem. Metaphors are great! We should be using *more* of them, not fewer. The use of metaphor is, I think, indispensable to the growth of a body of useful concepts, to the progress of inquiry, and to the growth of human knowledge. Philosophy that abstains from metaphor isn’t just cold. It’s dead.

I don’t mind having to look cultural specific jargon’s up, insofar as I can somehow find them, even if it does take up more of my time. I did notice some annoyance when I submit stuff to journals though, especially ones with stricter word limits. At a slightly earlier stage, I tried to incorporate examples from my culture and country of origin, but I soon noticed that I either had to spend lots of words explaining the examples, or face rejection due to a perceived lacking of credibility. Furthermore, the employment of those examples seems to suggest that my English is poor. Once I’ve received reports with one saying that the writing is beautiful and the other basically recommending rejection based on my inability to write proper English. Maybe a bit off-topic, but I really want to put this out.

Just to clarify my position (and I think the position of most others on my “side”): I’m not saying that the use of metaphor is a problem. I also think metaphors are great. But the current reality is that many philosophers use metaphors without acknowledging them *as* metaphors. That lack of acknowledgment, more than anything, is what causes the gaps in understanding.

(Also, in my previous post I meant to say “x is an *in*eliminable part of y”. Oops!)

I’m on board for jargon but not, I think, for idiom or metaphor (at least, not for most of the examples cited here). All three are frequently misused, and that certainly doesn’t help, but I’m only really bothered by the veneer of rigour that comes with overmuch jargon.

As a note: I can never remember what ‘pro tanto’ means. I look it up and it goes in one eye and right back out the other. And its use in context (e.g. ‘a pro tanto reason’) usually only makes things worse for me. I think it must be a blockage on my end.

Jonathan Livengood, thanks! Yes, I think there are proper and improper uses of metaphor, but I think Peter’s right on the money when he says we don’t acknowledge it, and that’s bad. Sure, the use of metaphor can produce a new application or connotation of a word, in a way that makes our language more expressive. But this creative use is not what I have in mind. Recently, I read over a draft of a paper and I had written something like “x points toward y” — and I thought, yuck! What does that mean? This isn’t expansive or creative. Rather, I was being lazy and using imprecise metaphorical language, not acknowledged as such. And this is different than self-consciously employing a metaphor in order to explain or illustrate a difficult concept or relation.

I notice this kind of thing more and more in published writing, and increasingly in analytic philosophy. I don’t work in contemporary analytic, but as an outsider, this kind of thing is irritating. They all are supposed to be the clear and precise ones, and this is how they (some of them) write?

Re: Daniel Weltman

I’m not sure I agree with the point about “local flavor”. I too enjoy learning about interesting expressions/examples from different cultures. And as a non-western international student and non-native speaker, I personally do enjoy learning about American idioms/culture. But given the sociological fact that so much of contemporary philosophy is produced by the US academia, having a lot of “local flavor” would mean that international students and scholars de facto often *have to* learn about the *American* culture, which is an extra burden that native speakers/American students don’t have. (Even more so given what “Yet another international” says above: using examples/expressions from a non-western culture can be very difficult.) I’m not sure whether this is a good thing given that philosophers hope the academia can be more inclusive.

Others have already defended the use of metaphor. They are often very fruitful of great ideas. Indeed, they are used in science, a most creative activity. Think of Darwin’s appeal to the notion of natural selection. Indeed, a lot of analogical reasoning relies on metaphors.

“*Dying metaphors*.—A newly invented metaphor assists thought by evoking a visual image, while on the other hand a metaphor which is technically “dead” (e.g., iron resolution) has in effect reverted to being an ordinary word and can generally be used without loss of vividness. But in between these two classes there is a huge dump of worn-out metaphors which have lost all evocative power and are merely used because they save people the trouble of inventing phrases for themselves. Examples are: Ring the changes on, take up the cudgels for, toe the line, ride roughshod over, stand shoulder to shoulder with, play into the hands of, no axe to grind, grist to the mill, fishing in troubled waters, Achilles’ heel, swan song, hotbed. Many of these are used without knowledge of their meaning (what is a “rift,” for instance?), and incompatible metaphors are frequently mixed, a sure sign that the writer is not interested in what he is saying.” (Orwell, ‘Politics and the English Language’)