The Good and the Bad of The Good Place

The Good Place, a sitcom set in the afterlife that takes up the question of what makes for a good person, has a professor of moral philosophy as one of its main characters, and regularly name-checks philosophers both living and dead, will begin its fourth and final season this Thursday.

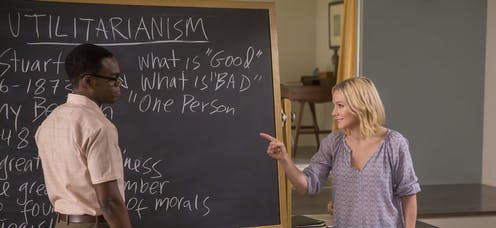

Chidi, a philosophy professor back when he was alive, tries to teach Eleanor some ethics. (The Good Place)

It is worth noting just how unusual the show is. For one thing, a glaring implication of its setting is that all religions are mistaken about the afterlife (one of the characters says that each religion was about “5%” right about the afterlife, and that the closest any human got to accurately describing it was a dude in the 1970s who was high on mushrooms at the time and promptly forgot it). For a network show (it airs on NBC) in the highly religious United States, this is gutsy.

For another, the show does a pretty good job, considering the confines of its 22-minute format, of teaching its audience a little—just a little—about moral philosophy. The ethics professor character, Chidi, not only discusses the basics of some philosophers’ ideas but also, through his indecisive character, accurately relays the fact that moral philosophy’s big central questions remain unsettled. (Update 9/26/19: see this Vox article for an appreciation of the show’s philosophical aspects.)

I’ve watched the first three seasons of the show with my kids (who over that period have ranged in age from 9 to 15 years old) and we’ve enjoyed it. So have many philosophers, judging from social media.

Part of the enjoyment of the show for professors and students of philosophy comes from simply recognizing the authors and ideas discussed on it. Who would have thought that T.M. Scanlon’s What We Owe To Each Other, which (as I think even Professor Scanlon would admit) is not the most reader-friendly work in contemporary moral philosophy, would not only be discussed, but serve as a key prop, in a television show watched by millions of people?

Further, the show and the various articles about it in the popular press function as a kind of public philosophy, reaching people who might not otherwise be consuming products of contemporary culture so obviously about philosophy. Also, to the extent to which mere unfamiliarity with philosophy among incoming college students in the U.S. contributes to low enrollments in philosophy courses and small numbers of philosophy majors, it is no surprise that philosophy professors would be happy about a show that has the side effect of advertising philosophy.

And the show can be funny, with humorous exchanges among the main players, background puns, running gags, and the comic delivery of D’Arcy Carden, who plays Janet, a sort of AI genie (here’s an entertaining video focusing on her character—note it contains spoilers for the first few seasons).

Still, I have not been inclined to recommend people watch it. This is because the show, while better than many network sitcoms, is just that—which isn’t saying much.

For me, the main weakness of the show is that its characters are paper-thin caricatures who make decisions that are implausibly foolish even for their cartoonish personalities.

This itself is not necessarily a flaw—the characters on Arrested Development were similarly shallow and stupid. The difference is that Arrested Development acknowledged the one-dimensionality of its characters. It was built around the idea that they were not to be thought of as real people to be empathized with or learned from, but rather more as walking jokes to be inserted into increasingly absurd and complicated Rube Goldbergian plots for our amusement—clearly influenced by the Seinfeldian comic aesthetic that renders a “very special episode” of the show unimaginable.

The makers of The Good Place, by contrast, seem to expect to be able to make its audience feel for its characters, to be concerned about them, their personal growth, and their relationships—not just for comic payoff, but because they want us to believe that the characters and their stories are themselves worth caring about and learning from. But they’re not, and so subplots that depend on emotional connection are undermined by the unrealistic superficiality of the characters.

It may be complained that the show is clearly not meant to be realistic and that I’m hoping for too much. But it’s not the lack of realism that’s the problem. Consider BoJack Horseman. This animated show is completely unrealistic—it features humans and a nonsensical variety of anthropomorphized animals populating an absurd world. Yet despite that, it is among the most emotionally rich comedies ever to appear on television—not to mention very funny.

Princess Carolyn, alone at her office late at night, when her phone informs her it is her 40th birthday. (BoJack Horseman)

These other shows work well because their their aims match with what they offer. Arrested Development expects us to be amused, and fulfills that expectation by giving us silliness—clever and hilarious silliness but basically just silliness. BoJack Horseman wants its audience to not just be amused but moved, and to do that it gives us not just absurdity and layers of jokes but also moments of gut-punching despair and recognizable personal struggle experienced by interesting characters.

The Good Place is at its best when it’s just going for laughs; when it reaches for depth and feeling, it struggles, owing to the absence of characters worth caring about. Despite its innovative aspects, in this important respect it is a very ordinary sitcom, reminding me of Gilligan’s Island. On that show, a bunch of one-dimensional characters are trapped on an uncharted island, hoping to escape, contending with random obstacles, each other’s bumbling, and false hopes—so the two shows have a lot in common. Now imagine if the writers of Gilligan’s Island attempted to explain Skipper’s constant berating of Gilligan with flashbacks to Skipper being yelled at as a kid, or tried to make you really care about whether, say, the Professor and Mary Ann hooked up, but without otherwise changing the characters, and you’ll get a sense how I feel sometimes watching The Good Place.

Opinions about this will of course vary. In Rolling Stone, critic Alan Sepinwall calls the show “wickedly smart” and says it “pushed the limits of where a sitcom can go—physically, metaphysically, stylistically, and philosophically.” Maybe. If he’s right, here’s hoping that the shows that follow The Good Place in this now less-constrained world of sitcoms take us viewers to an even better place.

— Justin Weinberg

I’m not sure if these are the more relevant comparisons. I’d think Big Bang Theory serves as a better comparison. Part of the aim of both the shows is similar. At least some physicists loved Big Bang. My physicist turned climate scientist professor loved making Sheldon allusions. His engineer turned climate science students as well humanities students loved those allusions. But while for those in the discipline it might have been loved as a TV show because it made the discipline popular and appear cool, as a non-physics viewer I learnt nothing about the discipline’s principles. On the other hand, Good Place does start ‘just a little’ on the road to explaining ethics to viewers. At times, I’d say it even hints at metaethics (for instance, Michael’s failure to comprehend the value of ethical thinking owing to the fact that he is immortal unless he retires). The Good Place wants to be actually about philosophy rather than merely philosophical.