The Margins of Philosophy (guest post by Peter Adamson)

“We need to understand the ‘minor figures’ to understand the ‘major figures’ adequately. But that’s not the only reason to be interested in minor figures, or to bring them to the attention of a wider audience. There is also the fact that apparently minor figures are sometimes major figures.”

The following guest post* is by Peter Adamson, Professor of Late Ancient and Arabic Philosophy at Ludwig Maximilians Universität. He is the author of Philosophy in the Islamic World and he runs the philosophy podcast History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps. He’s on Twitter as @HistPhilosophy.

This post is the fourth installment in the “Philosophy of Popular Philosophy” series, edited by Aaron James Wendland, a philosopher at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow. He tweets @ajwendland.

The Margins of Philosophy

by Peter Adamson

How much would you say you know about Miskawayh? Nāgārjuna? How about Lucrezia Marinella, or Henry Odera Oruka? Probably not much. In fact, you probably haven’t even heard of them.

These thinkers very rarely feature in the teaching of philosophy, and their writings might well be absent at a well-stocked university library in Europe or North America. They do not belong to that select group of philosophers that just about everyone has heard of—Plato, Aristotle, Aquinas, Descartes—or even to the list of figures that the average professional philosopher has heard of. They are, in short, “minor figures.”

I have given a lot of thought to the importance of such figures, because I produce a series of publicly accessible podcasts on the history of philosophy “without any gaps,” and also because in my own research I often find myself working on them.

I have published a couple of articles about Miskawayh, for instance. He was a historian and well-read philosopher who lived in the eleventh century, and his status as a minor thinker is in truth well-earned. Unlike his near contemporary Avicenna, Miskawayh was not one of the most brilliant and disruptive thinkers in human history. To the contrary, most of his writing is derivative. So why would anyone, even a specialist in philosophy of the Islamic world, spend their time reading and writing about him?

Though Miskawayh was creative in his synthesis of his sources and wrote a treatise on ethics that was fairly influential, the answer is precisely that he was not stunningly innovative. Miskawayh gives us an insight into a mainstream style of philosophy, combining Islamic piety, Aristotelianism, and Neoplatonism, that the more innovative Avicenna was reacting against. This is a common phenomenon: we need to understand the “minor figures” to understand the “major figures” adequately.

But that’s not the only reason to be interested in minor figures, or to bring them to the attention of a wider audience. There is also the fact that apparently minor figures are sometimes major figures. Avicenna is an example. He was the most important philosopher of the Islamic world by a huge margin, and he had far-reaching influence in other cultures too, especially medieval Christendom.

Much the same can be said of the second name I mentioned above, Nāgārjuna. His ingenious critique of the assumption that there are “independently existing” things in the world became the foundation of a whole branch of Buddhist thought, the so-called “Madhyamaka” or “Middle Way.” Nāgārjuna stature in Asian philosophy is similar to that of Kant’s in European philosophy. Nāgārjuna should really be a household name, at least in any house that holds people with an interest in philosophy.

My last two names, Marinella and Oruka, illustrate a further reason for paying attention to so-called “minor figures”: thinkers outside of mainstream philosophy often actively critique that mainstream.

In her On the Nobility and Excellence of Women, written at the end of the sixteenth century, Marinella attacked the misogyny of European culture, reserving special scorn for that most major of figures, Aristotle. Calling Aristotle a “fearful, tyrannical man” for his dismissal of women’s rational capacities, she went against nearly the whole tradition of European philosophical anthropology by arguing in favor of the intellectual and moral equality, if not superiority, of women.

Much more recently, at the end of the twentieth century, Oruka likewise challenged prevailing assumptions about who is capable of producing valuable philosophy. He defended the notion that philosophy can exist in purely oral cultures, developing a project he called “sage philosophy” that involved interviewing outstandingly wise members of traditional African societies.

These “sages” might not have written anything, but they can still represent the philosophical ideas of their people or—even more exciting to Oruka—push against those ideas by setting forth innovative positions of their own. Oruka’s project suggests that philosophy is not what we assume it to be, a tradition of argumentative writing, but something more like a lived wisdom that engages critically with the social setting in which it is produced.

At the moment, we are a long way from making philosophers like Miskawayh, Nāgārjuna, Marinella, and Oruka truly well-known, but steps are being taken in this direction. Podcasts and popular contributions that cast a wider net are raising awareness within the academy and being recommended to students. And I’ve heard from numerous colleagues that they are integrating Islamic philosophy into their teaching.

Doing this doesn’t need to mean devoting an entire course to the topic. Some associates and I recently wrote a series of blog posts for the American Philosophical Association suggesting how to integrate lesser-known figures from the Islamic world, India, and China into thematic courses on epistemology, ethics, and so on.

Of course, the “minor” figures mentioned above give you only a handful of examples. But I hope they suffice to convince you that it is worthwhile making less-known philosophers better-known. They can help provide context to understand the philosophical giants we already care about; they can turn out to be giants worth caring about in their own right; and they can change our ideas about what philosophy itself is.

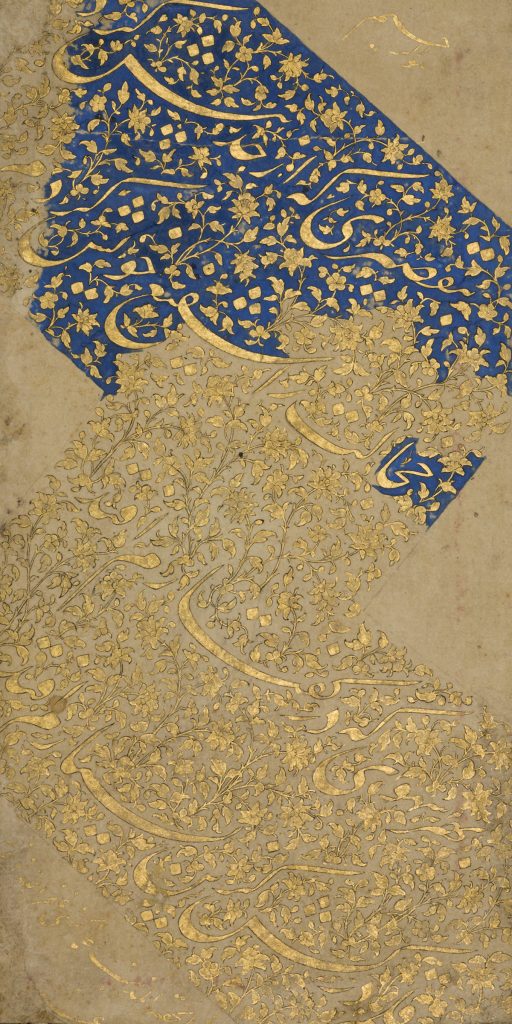

[image: Mir ‘Imad al-Hasani, Album Page with Calligraphic Composition]

One thing that would help would be if leading philosophy publishers would acquire the rights to, and then reissue, some of the books written by these figures, or to commission translations of them, etc. My bet is that the market is starting to grow, so one hopes this will start to happen. I know there is the Oxford New Histories of Philosophy series which is fantastic, but there is a lot of ground to cover.

I, for one, would love to get my hands on a copy of Oruka’s _Sage Philosophy_ with his own articles on sage philosophy, pieces by and about particular sages, and then with replies. It was published with E.J. Brill in 1990 but is now available pretty much only in libraries.

Philosophy Compass is also trying to help fill some of these gaps, with new Sections on African/Africana Philosophy, Indian Philosophy, Latinx and Latin American Philosophy, Native American and Indigenous Philosophy, in addition to our long-standing section on Chinese Philosophy. If you have an idea for a piece on a figure or topic, please feel free to send me a short proposal and I can make sure it gets in front of the right section editor.

Nâgârjuna is a “minor figure”??? Karl Jaspers included him in his “The Great Philosophers” over 60 years ago, not that you or I would want to take Jaspers as a model. I don’t remember ever talking with a philosopher who turned out not to have heard of Nâgârjuna, although they do tend to mispronounce him with the accent on the u. I would think the real problem isn’t that people haven’t have heard of him, but that they treat him as a saint and think it’s impossible, or missing the point, to give a critical examination of his arguments. I’m certainly all in favor of such critical examination.

Hi Stephen! All I can say is that you must run in better informed circles than I do. I don’t remember hearing his name when I was a student, for instance, and to be totally honest I knew basically nothing about him but the name until I worked on Indian philosophy for my podcast. Possibly I was unusually ignorant but I don’t think so. (And of course, as with Avicenna my point here was that he is in fact a very major figure and only “minor” in the sense that Western academic philosophy largely ignores him.)

Though it’s worth pointing out that the use of “major” and “minor” is not entirely consistent in this thread. You use “minor” here to mean “Western academic philosophy largely ignores”; but in response to Shahzad Ali, “major” means “incredibly important”. I realize this is nitpicking, but it might be worth establishing a more consistent use of the major/minor distinction.

Yes, of course part of what I was trying to do is question the minor/major dichotomy (I’d stand by Avicenna and Nagarjuna being in fact major figures, at least if anyone is). Ideally I would have had scare quotes around every use of the word “minor” in the piece, or said “supposedly minor” a lot, but that would obviously have been pretty annoying.

I did not hear about Nâgârjuna until I was ABD. Even then, I only heard about him because I was actively searching for diverse resources when I started teaching. I’d bet there are others.

Bryan Van Norden’s recommendations for readings on the Less Commonly Taught Philosophies has been very useful: http://www.bryanvannorden.com/suggestions-for-further-reading

I would welcome more suggestions for other minor figures in philosophy I (and others) should know about, as well as places/sites/journals/series where I can find out more about these figures. Philosophy Compass has already been named – what others are there?

Sir how can you included Avicinna in minor figures ? He has a very huge impact on philosophy..You Western intellectualls always underestimate our islamic philosophy…

I don’t think Peter Adamson did include Avicenna in his list of minor figures.

Nor is it very sensible to assert of him that ‘you Western intellectuals’ (a fairly lazy category) ‘always underestimate our Islamic philosophy’. He is a specialist in Islamic philosophy who, by talking about it with such erudition and enthusiasm on his excellent podcast and publishing a book about the subject, has probably done as much as anyone alive to popularize Islamic philosophy in the English speaking world.

You literally could not be more wrong.

If you read the piece again more carefully you’ll see the point I was making is that though a lot of people don’t know (much) about Avicenna he is an incredibly important, thus major figure.

I hope Justin won’t mind me mentioning that this is Peter Adamson’s “Philosophy Then” column in the current issue of Philosophy Now magazine (in a slightly different edit). A complete list of Peter’s columns in Philosophy Now can be found here:

https://philosophynow.org/categories/Columns/Philosophy_Then

Those of us who have been working to recover the women philosophers have been saying for years that women philosophers are worth reading in their own right and not just as minor understudies for ‘major figures’. Thanks to this work of recovery Lucrezia Marinella has been restored to view and her writings are available in English translation. Her example augurs well for the other philosophers who have fallen through the gaps in the history of philosophy, which Peter Adamson’s admirable project is intent on filling.