Uncovering A New Approach to Teaching Philosophy Texts (guest post)

“Texts can be challenging in multiple ways, some more useful than others…”

The following is a guest post* by Emma Kresch and Sophie Gitlin, who are both sophomores at Claremont McKenna College. They are working as research assistants for Dustin Locke, associate professor of philosophy at the school, on a new approach to introducing students to philosophical works that Dr. Locke is calling “Philosophy Uncovered.”

Uncovering A New Approach to Teaching Philosophy Texts

by Emma Kresch and Sophie Gitlin

We entered college having no prior knowledge of philosophy, but we thank Claremont McKenna’s general education requirements for leading us into our first introductory classes. In our philosophy classes we found wonder in the new ways to analyze the world around us, converse with others, defend arguments, and challenge old and new ways of thinking; we were hooked! However, there were days when we came to class too confused by the previous night’s reading to offer any insight to class discussion. Some of this confusion was due to the challenging nature of the arguments presented in our reading, but much of it was due to the fact that the essays were written in a way that we simply did not understand. This makes sense, as many of the essays weren’t written for us—they were written to be published in professional journals and read by professional philosophers. This is the problem that Philosophy Uncovered addresses, and we are excited be working with Professor Dustin Locke as research assistants on this new project.

Philosophy Uncovered will be a series of classic philosophical essays rewritten in a way that makes them more accessible to introductory philosophy students. The rewrites are not intended to summarize or analyze the original essays; they present the same argument, just in a more accessible form. The rewrites also differ from textbook explanations in that they present the arguments, so to speak, “in the first person”—that is, as if they were written by the original authors. When students read textbook explanations, they must deal with the extra cognitive layer created by the voice of the textbook author. Our rewrites allow students to engage more directly with the arguments of the original essays.

This project is still in its formative stages. However, we have preliminary drafts of rewrites for three essays: David Lewis’ ‘The Paradoxes of Time Travel’ (1976), Judith Jarvis Thomson’s ‘Killing, Letting Die, and The Trolley Problem’ (1976), and Michael Smith’s ‘What is the Moral Problem?’ (1994). We are happy to have instructors share these drafts with their own classes, and we would appreciate any feedback they may have to offer. Please send questions, comments, and concerns to Professor Locke at [email protected].

As Professor Locke’s research assistants, our role in Philosophy Uncovered is to provide a student’s perspective, shining light on what is confusing and what needs to be better explained in the rewrite. Before Professor Locke begins each rewrite, all three of us create our own outlines of the original paper and put them together to identify differences in our understanding. Our outlines indicate which parts of the argument were clear and which parts we missed or misunderstood. Professor Locke then drafts a rewrite based on our discussions. After receiving feedback from us, Professor Locke redrafts the rewrite and the process repeats until we are all satisfied with the paper. Professor Locke also revises the papers in light of classroom feedback.

Our project may invite some debate. Some might argue that part of the value of philosophy comes from the struggle to understand challenging texts. But texts can be challenging in multiple ways, some more useful than others. When a text deals with a complicated subject matter, or when it is written from a cultural perspective different from a student’s own, students often benefit from facing these challenges. But when a text is written for a professional audience—that is, an audience with a certain specialized body of knowledge—we believe the interpretative challenge faced by introductory students often does more harm than good.

Over the coming months we will begin to explore our options for publication. Interested parties may send inquiries to Professor Locke at [email protected].

(We are grateful to The Gould Center for Humanistic Studies at Claremont McKenna College, directed by Professor Amy Kind, for a grant to begin pursuing this project. The Gould Center is a wonderful resource for students and faculty at Claremont McKenna to study, research, and explore projects in the humanities.)

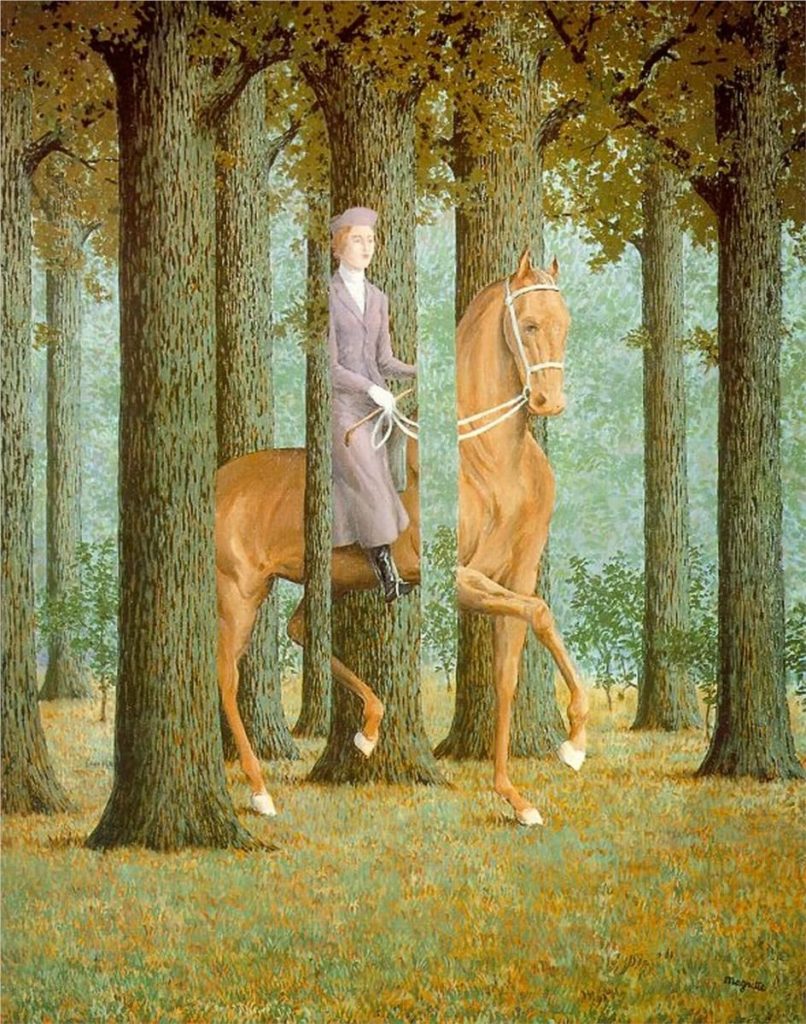

Art: René Magritte, “The Blank Signature”

This seems like a great project. I desperately wish, though, that you had named it “Philosophy Unlocked.” (The quarantine might be getting to me.)

Oh wow, I love this! It’s a more accurate description and just sounds better (not to mention the play on my name!). We’ve been trying so hard to come up with a better name. It was right in front of our noses! But “Philosophy Uncovered” is only the working title. Would you mind emailing me so I can get your first and last name to give you proper credit in case we go with this?

My goodness, your kind response has already given me a lot more credit than I deserve, so you certainly wouldn’t need to give me any further credit if you decided to go with this name. I’m just glad that you weren’t offended that I made a play on your last name!

Far more importantly, let me reiterate that this really is a great idea—it’s great that people will now have an easier time getting a grip on these works, and, as SCM points out, it could be philosophically enriching for the people who have a hand in producing them. Bravo!

Oh no I insist! Please don’t make me track you down.

Great effort! I am a teaching a course on Ethics this coming semester in our uni, and I’ll require them to read your rewrite of Thomson and Smith. Will send you feedback on the students’ reception of the materials. Thanks again!

*i’ll require my students…

What a fantastic project! Please keep us updated about its development.

1. This is an extremely valuable exercise for graduate students to do to hone their writing skills. I would encourage outsourcing much of the labour to interested graduate students — with perhaps different versions and integrated drafts of the same article. This will not only lighten the load on Dustin but benefit people other than the immediate audience of undergraduate students. It would perhaps be good if this project became a central clearing house for that activity.

2. It would be interesting to compare students’ reactions to the original articles before and after reading the rewrites. It’s good that they grasp the arguments in the text and can discuss them intelligently — and well-worked rewrites will do that. But another part of philosophical training is the ability to unravel complicated texts to figure out what the arguments actually are. Here, there’s no substitute for making them sweat through the originals. I’d think that much of the value of the rewrites is to get them to see how the arguments they now grasp can be uncovered in the original text. Metaphorically, we don’t want to just translate from the original Philosophese — we want them to become fluent in that odd language.

3. Definitely “Philosophy Unlocked.”

Reminds me of Jonathan Bennet’s https://www.earlymoderntexts.com/ , with its ‘translations’ into modern English of folks like Locke, Hume, and Mill (as well as Kant and a bunch of others). I’ve used Bennett’s texts in my intro-level classes, and this sounds like a good idea too.

Bless Jonathan Bennett for these—invaluable.

I really dislike those. Maybe it’s quixotic, but I think it an abdication of higher education’s responsibility to help students become less temporally parochial in their own language. I mean, Hume doesn’t need to be translated. The occasional note should be just fine!

They also occasionally put the reader at the mercy of Bennett’s interpretations of these texts, which are sometimes quite questionable.

Jonathan Bennett is a bit of a polarizing figure in the History of Philosophy circles. I love his translations, and use them all the time. I find all his interpretive points to be exactly right. His choices about which bits to leave out are right on the money (e.g. digressions in Sidgwick’s Methods that are completely irrelevant to the argument). Some historians seem to hate him, and not just for these translations. They’ve always hated him. I find that it’s the historians of the “we need to know what Descartes had for breakfast in order to figure out what he really intended by the Cogito” variety who hate him, whereas the historians of the “this argument suggested by this passage of Descartes may or may not be what he actually intended, but it’s worth considering in its own right, so I’m going to talk about it” variety love him. I am left almost completely cold by the former approach to history, but really appreciate the latter approach, so I am a big fan of Bennett. He was also my dissertation advisor (not on a history dissertation), so I know just how careful and meticulous he was.

I tend to agree with Led’s first comment here, and I would add that the mode and style of expression, the literary qualities of a canonical or classic work, are often part of a whole package that shouldn’t be ripped apart.

I can’t comment specifically on Bennett’s “translations” but I would think that often philosophers and other writers are making stylistic and literary choices that are meant to reinforce or exemplify their arguments. To get the flavor of the work as its author intended, the manner of expression has to be kept intact.

I think that’s likely true of, for example, Hobbes, Adam Smith, Burke, and Mill, and it’s definitely true of Marx; you wouldn’t want an English translation of Capital to “simplify” the German but just to render it as faithfully as possible — not because Capital is a sacred text or anything like that but because the mode of expression is, I’d suggest, often important or crucial to fully grasping the substance.

In a reading group at university, I struggled manfully to find out what “Marx really meant” in the opening chapters of ‘Das Kapital’. I failed.

It turns out that there are arguments in DK that are just wrong. Ian Steedman’s ‘Marx After Staffa’ shreds his approach to the Transformation Problem, for example. As far as I know no-one has produced a economically plausible and mathematically coherent account of the Tendency for the Rate of Profit to Fall.

I don’t want to sound like a prejudiced conservative here. There are equally trenchant criticisms of Bourgeois Economics. The Sonneschein Mantel Debreu critique of General Equilibrium, and the outcome of the 60’s Capital Theory debate are examples.

However interesting Marx’s ideas may be, their obscure mode of expression conceals errors and problems. I am one a graduate of an élite university. If I failed to understand them, God help the Working Class!

If you can’t express your ideas clearly enough that an intelligent and interested twelve year old can understand and ask intelligent questions about them, then you probably don’t fully understand them yourself. They are probably wrong to boot. I may be a Dreamer, but, surely, l am not the only one!

1) Where Marx was wrong and where he was right is a separate question, one that I did not address.

2) Capital v. 1 is sometimes a challenging read but much of it is not that difficult. Its literary qualities are noteworthy. You don’t have to accept all the economics to appreciate the descriptive and historical parts, e.g. Chap. 10 on The Working Day.

Wonderful project. I look forward to using some of these essays and more. Out of sheer curiosity: what do the living authors concerned by the project think of it?

Great project! I second SCM’s suggestion of outsourcing, maybe something along the lines of the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (eventually). Kudos on fantastic idea.

Another great teaching idea from Dustin Locke. Well done.

Perhaps to belabor the obvious, I’d think picking carefully which articles to rewrite is crucial. Some articles don’t need rewriting to be accessible to students[*], while in certain others the style may be so closely tied to the substance as to make rewriting inadvisable. That probably still leaves plenty of journal articles as candidates for this kind of rewriting.

The other thing is that I think it should be made crystal clear to students that they are reading a rewrite. No matter how good the rewrite, it’s not the original. It would be surprising if absolutely nothing were ever lost in the rewrite, and if indeed nothing of substance is lost, that might well be a sign that the original is not especially well written, irrespective of the intended audience.

[*] Probably everyone can think of at least one or two people who write so clearly, even in professional journals, that they don’t need rewriting in order to be accessible.

An excellent project.

Nobody teaches Newtonian physics by insisting on a close reading of the Principia.

This very nicely captures the spirit of the project. I’ll have to put that in our next grant application!

Thank you!

Anybody who could do this for the works of Kant and, perhaps Heidegger (my own least comprehensible geniuses) would be doing the world a great favour.

For Kant, Jonanthan Bennett has already done this as part of his “early modern texts” project: https://www.earlymoderntexts.com/authors/kant

Thank you.

But I am very annoyed. You have undermined my excuse for not studying him!

It strikes me though, that what I really wish philosophers would do is separate philosophical ideas from their progenitors.

If the idea stands parentless, I feel it would be easier to critically assess it on its own merits. If one is instead looking critically at, say, ‘Kant’s Concept of the Categorical Imperative’ or ‘Hume’s Problem of Induction’, then one is challenging a person rather than an idea. One’s reaction to the idea is influenced by one’s general opinion of its author.

There are BOO philosophers:Marx and Heidegger come to mind, and HOORAY philosophers: perhaps Socrates, or JS Mill. Which of us can deny having our own heroes or villains. The Ad Hominem Fallacy lurks within us all.

What fun it would be to teach a first year course (‘Philosophy without Philosophers‘?) with all the names left out. Then perhaps set finding out all the authors as a final quiz!

Paul, I understand the basis for booing Heidegger, but what was Marx’s sin? I know very little about Marx’s life, so I am genuinely curious. As for Socrates, he was a bit of a mixed bag. I’m sure Xanthippe, Thrasymachus, Euthyphro, and quite a few more of his interlocutors were often inclined to boo him, and with good reason.

What was Marx’s sin? A thought provoking question.

I didn’t call him a BOO Philosopher because I didn’t like him myself. But many others do.

Having said that, after being attracted in youth, I see little merit in his ideas now.

His ‘sin’ was to see the problems of the world to have a singular cause, Capitalism;

proposing a simplistic solution, Socialism;

and advocating so persuasively that even after his death, millions of people believed them and acted to contravene all standards of common morality, leading to the deaths and suffering of millions of people.

Then I thought again.

Couldn’t one say the same of Jesus Christ?

Oops!

I don’t think you should add that to your next grant application because it’s not true: St. John’s College in Annapolis and in Santa Fe has every junior read large portions of the Principia, slowly and over several weeks. It is in fact a rich way to find one’s way into Newtonian physics, which kind of supports your research assistants Emma and Sophie’s point: Newton isn’t a prime candidate for rewriting because he didn’t imagine himself to be writing for a professional audience.

As a graduate of St. John’s College, I would like to clarify that the point of closely reading Newton’s Principia is not so much to learn Newtonian physics or even to learn about the historical development of physics. I agree with David Wallace (below) that this is not a good way to learn about modern science. Instead the point of reading Newton’s Principia is to learn how he to solved the problems he set for himself. This is the same reason students at St. John’s College study other outmoded works in the history of science such as Aristotle’s physical and biological works, Euclid’s Elements, Ptolemy’s Almagest, etc.

And, just to be clear: there is a great deal to learn from the Principia!

I’d use caution with this analogy. Not only does hardly any physics student (William Day notwithstanding) learn Newtonian mechanics from the Principia, hardly any professional physicist spends any time studying it (and when they do it’s usually for philosophical or historical reasons). Physics has genuinely progressed since Newton, and a huge amount is understood about Newtonian mechanics that Newton didn’t understand. But (I take it) there’s no parallel suggestion here that professional philosophers who want to work on, say, Lewis on time travel will be able to read only the rewritten version.

Philosophy UnLocked

Everyone seems to think this is a great idea, so allow me to play devil’s advocate. My concern is the following. A huge part of the process of learning philosophy and developing your critical thinking and reading skills is by slogging through and wrestling with extremely difficult texts. Personally, I find it very rewarding when, after a longer period of time, I can go back to an article that I did not understand the first time around and comprehend it to a far greater degree. That is lost with a project like this. Isn’t this just another example of a decline in educational standards? I can almost guarantee that undergraduates will not go back to read the original article.

To be fair, they do mention and respond to this concern–by saying, sensibly, that not all difficulty in a text is equally productive. That seems clearly true. For instance, assigning texts in foreign languages would also make them more difficult, as would redacting every third word, or making students read while standing on their head. The students’ contention is that some of the difficulty of reading canonical primary sources is like that; philosophers writing for other professional philosophers in a particular time period will have idiosyncratic concerns, conventions, and stylistic choices which introduce needless interpretative difficulties for contemporary students. Perhaps they are wrong, but as far as hypotheses it seems perfectly plausible to me. It’s also thoroughly empirical. So, good to see them testing it!

Absolutely. Also, the project doesn’t mean to disregard the original texts. And if it does help students face interpretive challenges in the original texts, and it is assumed that those challenges are worth confronting , then the project has something to contribute.

Worst case scenario, you go back and read the original.

“A huge part of the process of learning philosophy and developing your critical thinking and reading skills is by slogging through and wrestling with extremely difficult texts.”

Here are two things that contribute to a text’s being extremely difficult: (a) it deals with complex ideas and arguments; (b) it uses language that is difficult to understand. It seems to me that the philosophical value of engaging with such texts lies mostly in the (a) rather than the (b) area, so if we can preserve (a) while reducing (b), doing so seems like a good idea.

Once upon a time a professor failed a student on a quiz. “But the question wasn’t accessible for me,” the student complained. Upon reflection the professor changed the grade to F* (* = “when students cannot answer correctly, fail the question, not the student”).

Hi, Tom.

I think we always have to work out teaching solutions that keep in mind these competing pressures:

1) Students who arrive at university tend to be far less literate and far worse educated than they were a few decades ago;

2) It would be very wrong indeed for us to water down our undergraduate curricula so that underprepared students can pass; and

3) It would also be undesirable to construct courses such that most registered students cannot pass them.

The general scheme of the solution seems straightforward enough: create philosophy curricula that ensure that graduating majors are working at a high level, but that are accessible enough at the freshman and sophomore levels that historically ignorant and not-very-literate students still have a fair chance of success if they put in the required work. Naturally, this means that the slope from freshman to senior level must be considerably steeper than it once was: that’s the fault of the decisions of the people over in university admissions and the K-12 system. We can only deal with what we’re given.

A student entering a freshman-level or sophomore-level course and given a bunch of readings from Hume, Mill, and Aristotle needs to learn a number of things simultaneously, including:

– How to parse and understand the sentences in the text (difficult, because many of the students have never learned an iota of grammar and have never been asked to read and understand anything more than a few decades old);

– The general historical background one needs in order to be able to interpret the texts (if you don’t know why Hume couldn’t just come out and argue against Christianity in the way that an atheist bestseller today does, it’s harder to get what’s going on);

– The philosophical positions and arguments under discussion.

It’s tricky to learn any of these things, but especially difficult to learn all three at once. As I see it, though, the last item listed is the most important one to get across if an introductory-level course is just too heavy for most of today’s freshmen and sophomores.

If one gets across only this in a lower-level course, those students who are just taking that one philosophy course as an elective will at least learn what philosophy is and (one hopes) be able to apply philosophical thinking elsewhere. Meanwhile, the majors will take upper-level courses in which they’ll have to read the works in the original. I think that’s an efficient way of dealing with the problem without dumbing down the entire curriculum.

// A huge part of the process of learning philosophy and developing your critical thinking and reading skills is by slogging through and wrestling with extremely difficult texts.//

That was a huge part of your experience and my experience. Is it inherently part of the experience of learning philosophy and developing critical thinking? If so, how so?

Probably a good idea to get signed releases from holders of copyrights. What this project is doing (courts would deem it “paraphrasing”) may constitute actionable infringement. There’s a line between fair use and sentence-by-sentence rewriting of entire works. Think about it. Were this done to an article of mine without my permission, I’d feel violated. // Since the dawn of the university students have struggled with texts. Never have we said to them, “Go now and rewrite these pointlessly elusive works in your own words, and we’ll assign your versions instead. For no student should endure your struggles, evermore.” (Rather, we’ve invited them to write commentaries.) Just wait until the next generation finds the paraphrases too difficult. The eventual result is bowdlerization. I applaud these students for working so hard to comprehend and communicate! How about sharing study notes instead of rewrites?

It does seem like a legal problem but your tone implies it is also unscrupulous or academically dishonest.

Unscrupulous, dishonest acts don’t tend to involve proud, candid guest blog-posts, Miguel! Were this questionable practice found to involve improper paraphrase infringement, it’s not the students I’d fault. It’s tenured faculty who should know better (and who should promptly chime in on this thread if releases were in fact secured from the rights holders). Unscrupulous, no. Careless and unfortunate, perhaps. Here we have a respected institution of higher learning, apparently both remunerating those involved and inculcating the notion that this paraphrasing activity is not only permissible – it’s commendable. The subject matter of the syllabus and the paraphrased works? Ethics. No irony there …. A term paper on why a legally improper act like copyright infringement is still the ethical thing to do under a utilitarian construct, but perhaps not a deontological one: now there’s a scrupulous, honest assignment these hard-working students might better tackle. (Their post here rightly acknowledges the project is morally debatable and begins to frame the benefit-cost arguments thoughtfully.)

Hello! I’m a philosophy specialist from UofT and a graduate student in education. I would love to help any way I can.

I like this more for the process than the product. Having students spend some time just trying to rewrite a philosophical text in their own words is a great exercise.

I am reminded of the perhaps apocryphal story about the Spanish guitar master Andres Segovia, who once had a student so distraught by the fact that he would never be able to replicate Segovia’s technique that cut hos own right hand off! If someone said to me, “here, take this work by David Lewis and make it better and easier for people to read.” I don’t know how i possibly could?

As it happens, I rewrote the entirety of “On the Plurality of Worlds” and made it immeasurably better. (Just not, admittedly, in this world — not that that should matter.)

I for one love the tradition of George Boolos’ “Godel’s Second Incompleteness Theorem Explained in Words of One Syllable”. I once did that for Anselm’s proofs, and the challenge did reveal to me my own level of understanding, and improved it. I searched in vain for the site that once promoted this.

Thanks for the link to the Cocoon’s new rendition of this Justin! Now if I could only find my ontological arguments versions. . .

Found it! 🙂