Anti-Trans Discrimination in Philosophy of Religion: An Accusation & Possible Progress (Updated)

A professor of philosophy says she was told by the organizer of a conference on theology and philosophy of religion that he would not consider papers from her for conferences like that because she is transgender.

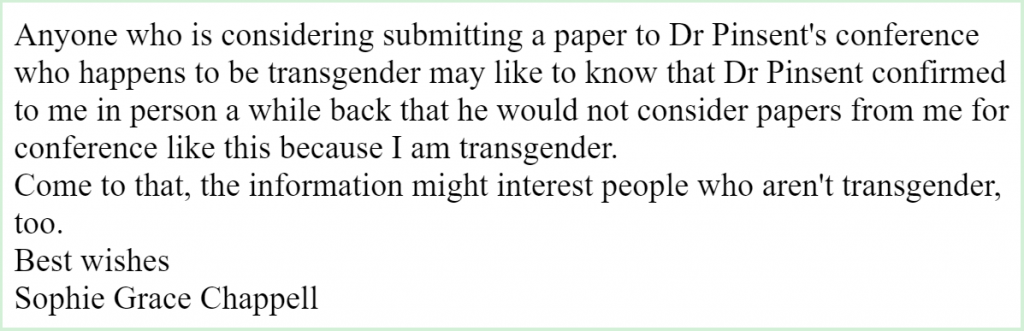

Sophie Grace Chappell of Open University says of Andrew Pinsent, a member of the theology faculty at Oxford University:Dr Pinsent confirmed to me in person a while back that he would not consider papers from me for conference[s] like this because I am transgender.

Chappell made her remarks on PHILOS-L, a large philosophy listserv, in response to a call for papers posted by Pinsent last Wednesday for an upcoming conference on natural theology at Oxford he is organizing.

You can view her post here.

In an email, Dr. Chappell said the aforementioned exchange with Dr. Pinsent took place in 2017.

Dr. Pinsent denies the accusation. In an email, he wrote that “is not only false but literally and demonstrably false.” As evidence against him saying such a thing, he cites a 2015 email to Dr. Chappell in which he tells her she may “be interested in our summer conference in Oxford, which we shall be advertising shortly.”

On the webpage for the conference he is organizing, Dr. Pinsent added this note about Dr. Chappell’s accusation:

I state here that this claim is completely false and that the conference is open to anyone. To extend an olive branch, I have written to Prof. Chappell offering to reserve a place at the conference for her. Given the seriousness of this public defamation, against me and the University of Oxford, we are, however, also following up this matter with PHILOS-L and taking legal advice.

Via email, Dr. Chappell said that though she called out Dr. Pinsent publicly, they used to be friends and “there is much about him that I like and respect.” She also expressed hope for “a positive outcome from all this… not a destructive one.” Dr. Pinsent’s statement that the conference is “open to anyone” and his inviting Dr. Chappell to it seem like positive developments—the implicit threat of a lawsuit not so much. Dr. Chappell hasn’t said whether she is accepting the invitation.

The publicity of the case is perhaps both a sign of progress and a potential cause of it. That Dr. Chappell felt that it was worth making this accusation in public is an indication of confidence that enough others in the profession would find anti-trans discrimination problematic enough to do something about it. It wasn’t always so. Looking forward, others who are organizing events in philosophy of religion and theology may be motivated to take steps to not be subject to similar accusations.

(Readers may be interested in Dr. Chappell’s “frankly autobiographical” reflections on “transgender in theory and practice.”)

I asked one of the conference’s scheduled keynote speakers, Helen De Cruz (Saint Louis University), if Dr. Chappell’s accusation and Dr. Pinsent’s reaction to it were going to have any affect on her plans to attend the conference. I reproduce her response, in full, below.

I have been asked to provide a comment in light of a recent situation that arose about the conference Natural Theology in the 21th Century, where I am one of the keynote speakers.

The space of philosophy of religion is a difficult one to navigate. Whereas philosophy is quite liberal, philosophy of religion reflects a greater diversity of political views, including on gender issues. I find it fascinating to work in this space, and I greatly value conversations with people across the political spectrum.

This greater political diversity also means though that philosophy of religion is less welcoming to transgender and other LGBTQ+ people than many other philosophy fields are. This is regrettable and unfortunate. As I’ve argued (in a forthcoming paper), we need to seek epistemic friction, and this includes challenging prevailing religious orthodoxies on gender and sexuality (I think that there is also a place for these views to be discussed, but I know other people disagree with me on this).

In situations like the one I am commenting on, it is often difficult to separate the personal and the professional. Let me clarify, in case it escaped people’s notice, Sophie Grace Chappell did not say in her original message that discrimination against trans people would be conference policy. Still, individual trans philosophers experience rejection on an individual basis. This is independently the case from any conference policy.

In the interest of full disclosure: Andrew Pinsent has been a mentor and invaluable help for me when I was a postdoc at Oxford, and also later. I greatly value Andrew’s philosophical work, I also value Andrew as a person, and I owe a debt of gratitude to him. So, given this situation, it was a torn and difficult decision to know what to do. I do not wish to appear ungrateful, I don’t wish to pretend this issue hasn’t happened.

Not presenting at the conference was an option, but I felt that there are several disadvantages. First, my non-appearance would not make clear what, if any, my reasons would be and might give rise to the impression that I was just succumbing under pressure. I could easily see how my conservative philosophers of religion friends would cry out “cancel culture”, or say that I am just another liberal not worth engaging with. However, I hope (and Sophie Grace Chappell told me she shares this hope) that her willingness to step forward affords us with an opportunity for us to change the field for the better.

Individual cases like these are helpful for us as a wakeup call, but the danger of focusing on them for the sake of “drama” in the profession is that we sometimes lose sight of the larger picture, namely that philosophy of religion is still by and large unwelcoming to transgender people (and other people who are LGBTQ+). One could put this down to deficiencies in character, but I here wish to focus on the structural issues.

Philosophy of religion also still has a long way to go to be more open to traditions outside of Christianity (and to a lesser extent naturalistic atheism), and to be open to people of color and people with disabilities (the issues here is that lots of traditional theological interpretations of scripture are ableist). There are still very few people of color like me who are members of the Society for Christian Philosophers and other Christian philosophical spaces. The situation for women is getting better, but judging by low numbers in the field, can still be improved substantially.

There are still very big obstacles for trans philosophers. I am hoping we could take this opportunity to draw attention to this issue. As I said, not presenting is an ambiguous statement of some sort, and so is presenting without any explanation. When I will present my paper, I intend to spend the first five minutes on expressing my solidarity with trans philosophers of religion, outlining the problems they face (I will ask feedback from several such philosophers to make sure this sounds on track but I will refrain from mentioning any specific cases), and conclude in expressing the hope we will be more inclusive. I hope this will change the hearts of at least some philosophers of religion.

I know that several philosophers of religion disagree strongly with me on the metaphysics of sexuality and gender. But I don’t think we need absolute agreement on this score. What we need is to be mindful of each other, respect each other’s pronouns (this is a courtesy you can extend even if you are gender critical), and try to make the space more welcoming. I will spend the remaining time of my talk talking about Schleiermacher and our taste for the infinite. I hope I am still welcome to come and present at the conference under those terms.

Some people might object to my idea that we can separate philosophical discourse from being welcoming to transgender people. I think this is right, it’s impossible to separate them. Trans philosophers go into spaces knowing that many people within it will not take their gender identity seriously. That must be hard, and I commend the courage of Sophie Grace Chappell and other trans philosophers (some of whom are out, not all) to navigate spaces under those conditions.

But we live in a non-ideal world, so I think what we can do is at least welcome those courageous trans philosophers balancing that with the need for openness to differences of opinion. I particularly hope we can shift the culture in conferences with a focus on Christianity where it seems to me the issue is more pressing than in conferences that have a broader focus (I cannot speak from experience of any conferences focused on any non-Christian religion). I am reminded of Paul’s letter to the Galatians: “There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” I have always taken this to mean not literally that we don’t have gender or religion or that the realities of oppression would simply vanish under a Christian identity. Rather, I take it to mean that under a Christian identity, those things ultimately don’t matter. It does not matter who you are, you are loved and valued for who you are. That’s a powerful message I hope we can take more to heart in philosophy of religion conferences.

UPDATE (3/4/20): Dr. Pinsent sent the following to me (and has now also posted it to PHILOS-L):

A statement by Andrew Pinsent, approved by Sophie Grace Chappell on 3 March 2020:

To close some issues that have arisen recently between myself and Professor Sophie Grace Chappell, I state definitively and finally that there is no policy against transgender persons at the Ian Ramsey Centre. And I personally invited Sophie Grace Chappell to our 2015 conference and have now also invited her to our 2020 conference. So she might, in fact, be our most invited single speaker of recent years. Finally, I have also been in direct contact about this matter with Sophie, who has been a personal friend and respected colleague for most of the last thirty years. Although we have our disagreements, we have also discovered some significant misunderstandings that we are able to address together.

■ ■ ■ ■ ■

I’m a bit concerned about this report of what is effectively an unconfirmed allegation. Is it really appropriate for us to be trying to think through something that maybe didn’t even happen, can’t be corroborated by any text or email, and so on?

And now the conference organizers are on their back foot for it, keynotes with no first-hand knowledge are weighing in, etc. As a community, this stuff tends to promote acrimony, distrust, and all sorts of other things. Whereas perhaps the most accurate representation is far simpler: maybe there was a miscommunication, it’s been rectified (through the invitation), and we don’t need to be alarmist about “anti-trans discrimination in philosophy of religion”–which probably oversells what’s going on.

Sure, there’s all sorts of nefarious discrimination in the world–some trans-related–and we should be vigilant. But there’s not always evil everywhere, and this feels more like click bait than a real thing. (Hypothesis: most people would have expected a stronger case, given the headline.)

Can you explain why you don’t trust Prof. Chappell’s first-person testimony here?

This is just a wild guess, but it may have something to do with the testimony and evidence provided by Dr Pinsent. (And Jon Light didn’t say the allegation was false, not even that it is probably false.)

Presumably because, if we made a practice of treating completely unconfirmed first-person accounts of what someone else said as though they were clearly true, even when the person who allegedly said the thing in question denies it and we risk seriously harming someone’s reputation by treating the claim as though it’s true, society would fall apart. Moreover, we ourselves would seriously risk becoming, by spreading such stories around and acting against the reputation of the person in question, guilty of injustice.

Why this is mysterious to anyone who has given such things the slightest amount of thought is utterly bewildering to me.

I would not wish to have the power to seriously and permanently damage someone’s professional reputation merely by presenting an unconfirmed paraphrase of what I recollect was said to me. Even if someone said something deeply objectionable to me in private and I mentioned it to others, I would find it terrifying if others who didn’t know me well enough to absolutely trust my word were to treat my mere say-so as sufficient grounds for harming another person’s reputation without a word of questioning or a moment of doubt. That is not a power anyone should have.

Justin Kalef, actually the scenario you describe would make for a great dystopian novel/movie

Because I have a defeater, consisting of Dr. Pisent’s first-person testimony

That isn’t the only defeater, either. Doesn’t it strike you as prima facie implausible that in 2017 a philosopher would say “I wouldn’t consider any paper submission from you, a transgender person, for a conference like this” or anything to that effect?

Especially with the easy and ubiquitous “Unfortunately, due to the unusual number of high quality submissions …”.

This again,

Can you explain why you don’t trust Pinsent’s first-person testimony?

Hi Dr. Weinberg, I found your comment “Looking forward, others who are organizing events in philosophy of religion and theology may be motivated to take steps to not be subject to similar accusations”, curious. I’m just wondering, what would such steps entail? What if Pinsent is completely innocent of these allegations? What further steps could he have taken?

Thanks for your time!

”Looking forward, others who are organizing events in philosophy of religion and theology may be motivated to take steps to not be subject to similar accusations.”

As already mentioned, this is a deeply problematic sentence. If Dr. Pinsent did what he is accused of, it’s clear how he could have avoided not being accused of it – by not doing it. But if he did not do what he is accused of, it’s not at all clear what he should have done to avoid being accused of doing it. This seems rather clear and uncontroversial, so the oly reading under which the quoted sentence makes sense is that in which the speaker believes that the accusation is true. It seems to me that the evidence presented in the post does not warrant such belief.

One possible step: include a non-discrimination statement in the call for papers.

This might be thought to be a good idea especially for events in philosophy of religion given the dominance of Christianity in philosophy of religion and the common enough view that Christianity disapproves of actions particularly characteristic of LGBTQ persons.

This is probably too much but something that gets across the following would be good: “even though this conference will likely mostly be about Christian philosophy of religion and theology, we welcome participation from those who have traditionally been the victims of discrimination justified by appeal to Christian scripture, including members of the LGBTQ community…”

I don’t think singling out Christianity is a good idea here. Islam isn’t really fond of people with unconventional lifestyles and identities, Hinduism and forms of Buddhism aren’t fond of women who are menstruating, etc…

But there’s one more thing. Say, a conference organizer puts up such notice. Then someone accuses them of telling them in private that, despite the notice, they will not accept their paper because the disagree with their identity or lifestyle. What good is that notice then, in preventing the accusation? And if that notice would be a reason for us to suspend belief about the accusation (in the absence of other evidence), why isn’t Dr. Pinsent’s clear statement that he did not do what he’s accused of a reason for us to suspend belief about the accusation, unless more evidence resurfaces?

Because of that, I’m doubtful whether the practice of declaring such notices would prevent the issue at hand.

I mentioned Christianity because of what philosophy of religion is like now, and the broader social context in which typical philosophy religion conferences take place.

I think your comment is true only if restricted to a certain narrow brand of analytic philosophy of religion in the English-speaking and Christian-influenced world. Remove any of those conditions and I don’t think it can be truthfully said that Christianity enjoys such a “dominant” position.

-Your friendly neighborhood spider-man, ever eager to remind readers that there’s more to this life than the US and Europe

Why not instead just write: “submissions from anyone are welcome.”? Seems to be more straightforward. And if your’e feeling really fancy, include “anyone, regardless of race, gender, etc.”

I must say I’ve never been sure what the point of these statements is. If there were a generally accepted norm that discrimination was permissible, or if there were open clashes between those who favor discrimination and those who don’t, then saying that your conference won’t discriminate could convey important and reliable information. But in the present context, where it’s understood on all sides that anti-discrimination norms are generally in place, they don’t seem to be any more helpful than a sign at a store saying “All our prices are reasonable” or a t-shirt saying “Don’t worry, I’m not going to punch you.”

I’m not saying here that discrimination doesn’t exist or anything like that. But those who do discriminate today are generally quite aware that there are norms against doing that. If it becomes de rigeur to put such boilerplate into conference announcements, then the bigots will have no reason not to copy it along with everyone else.

Worse still, such announcements seem apt to make conference organizers feel that they are already morally special if they merely say such things, and this may have the effect of making them less careful to put into practice what they have just preached.

I’d generally +1 Justin’s proposed approach above. We’ve done similar for conferences I’ve organized wrt disability accommodations, in the body of the CfA. That’s an easy way to be more inclusive, and probably works more broadly.

That said, maybe not every conference is “about” LGBT issues. It’s not necessarily discriminatory to (genuinely) have a certain scope for a conference. Of course, discriminating against LGBT *people* won’t work, but that’d be substantially narrower than Justin’s proposal (maybe). In other words, do organizers really have to make substantive claims about who Christianity has (or hasn’t) *victimized*? As opposed to saying “all are welcome to participate, regardless of sexual orientation, gender identification, and [whatever].”

A thought: I’ve been on the receiving end of a lot of shockingly sexist comments, behavior, and jokes in the profession (I’m a cis woman). I’ve almost never called out any of those perpetrators, since it is costly and awkward to do so, but I have on a few occasions. Their responses? “That’s not what I meant,” “I wasn’t serious,” “I don’t remember saying that,” “I don’t remember doing that,” I’m sorry you felt offended, but… [explanation of why it wasn’t really offensive],” or even the most flagrantly gaslighting, “I didn’t say that.”

Not one time has any of these people said, “You’re right. That was sexist and offensive, and I’m sorry. I’ll do better.”

I don’t pretend to fully understand the psychology of this, but it’s only human to remember events in a way that puts one in a generous light, so I suspect that in at least some of these cases, the respondents aren’t deliberately misleading. They believe what they’re saying.

No idea what happened in this case, but I would venture to suggest that, just as there are reasons for taking seriously the first-personal testimony of sexual harassment and sex crimes, even when the accused issue denials (there are serious incentives not to report, all empirical evidence suggests rates of false report are extremely low for such incidents, etc.), so too is there reason to take seriously the first-personal testimony of sexist, transphobic, even when the accused issue denials. There are good traditional reasons, such as higher-order evidence, but there are also reasons from trust and centering marginalized groups.

This is of course not to say that all such claims are true or that counter-claims shouldn’t also be given weight. This isn’t even to suggest how we should assess this or other such cases, because straightforward implications in a messy reality are hard to draw out. But broader patterns and likely incentives on both sides matter. So too do reasons from the moral need to trust and center traditionally marginalized groups. Our responses should be at least partly shaped by these things, and many comments on this thread have ignored them entirely.