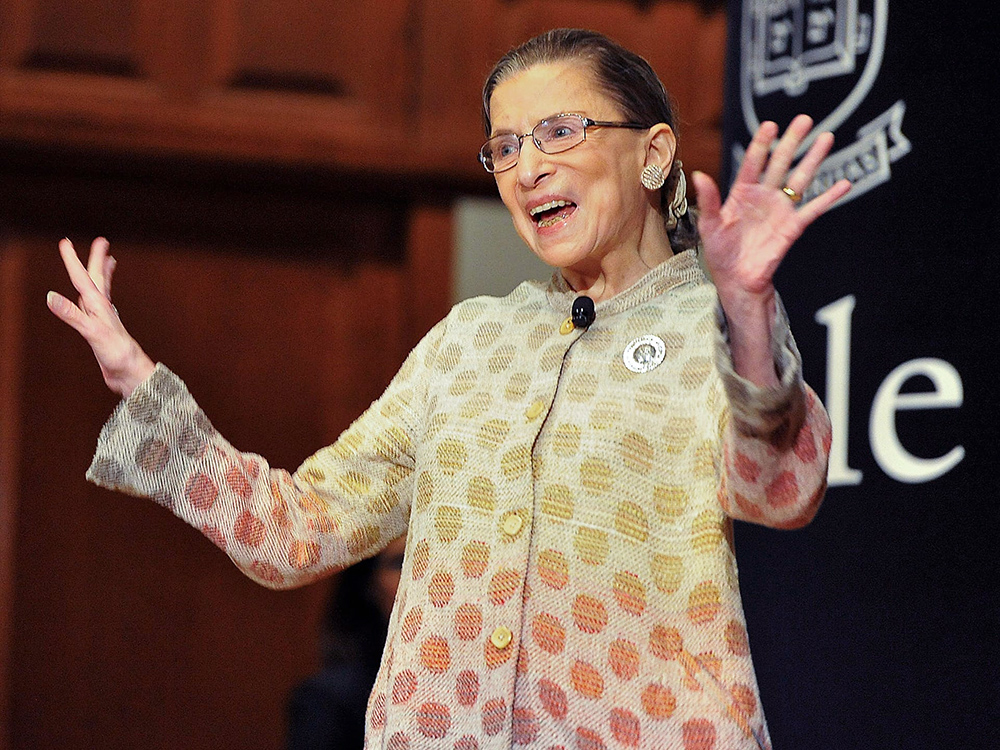

Berggruen Prize Awarded to Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg

The 2019 Berggruen Prize has been awarded to U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. This is the first time the award, established in 2016, has been bestowed on someone who is not an academic philosopher.

The previous awardees of the $1 million prize were Charles Taylor (2016), Onora O’Neill (2017), and Martha Nussbaum (2018).

The prize is awarded to “humanistic thinkers whose ideas have helped us find direction, wisdom and improved self-understanding in a world being rapidly transformed by social, technological, political, cultural and economic change.”

(Originally called “The Berggruen Philosophy Prize,” in 2017 the word “philosophy” was dropped from its name. It now seems to have made a reappearance on the Berggruen site and is now called the “Berggruen Prize for Philosophy and Culture”.)

The chair of the prize committee is philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah (NYU). Justice Ginsberg, he says, “has been both a visionary and a strategic leader in securing equality, fairness, and the rule of law not only in the realm of theory, but in social institutions and the lives of individuals.”

The prize is sponsored by the Berggruen Institute.

(via The New York Times)

I admire RBG’s jurisprudence, have great respect for the jury members, and have no doubts about the integrity of anyone involved in this process. (And I note from the Berggruen website that RBG is donating the prize money to charities and nonprofits.)

But even so, the principle is worth pausing on. I think there are serious issues that arise if sitting judges receive large cash prizes on the basis of the societal impact of their judgements.

If I change the political valence, and suppose that a $1M prize had been just been awarded to Neil Gorsuch by the Koch Foundation or the Federalist Society in recognition of his contributions to natural-law principles and to originalist approaches to the constitution, I suspect DN readers might feel somewhat differently.

“I think there are serious issues that arise if sitting judges receive large cash prizes on the basis of the societal impact of their judgements.”

What are the issues you have in mind? Your example merely suggests that we left-leaners wouldn’t like it if Gorsuch received such a prize for judgments that we would disapprove of.

It may introduce perverse incentives into the jurisprudential process. It may (at least unveil and perhaps) compound the problem of activism in the supreme court.

“Perverse incentives” is my concern, yes.

Yes, of course, but what might they be? One unintended consequence might be that judges become more likely to reach judgments whose impacts promote equality, fairness, and the rule of law. Will the perverse incentives you have in mind have negative consequences so great that reasons to avoid them outweigh reasons to bring about the potential positive consequences?

Bribing politicians to enact policies I like would, in isolation, by my lights have positive consequences. For all that, I don’t think it would be all-things-considered good for it to be seen as okay to bribe politicians.

(Though in view of David Chalmers’ comments below, I’m fairly reassured this isn’t an issue in this case.)

You see the award as a bribe?

If not, I don’t understand your point. If so, you have a strange way of seeing things.

I guess your point could be that awards can be used as bribes. But this is no reason to have a general worry about large cash prizes to sitting judges. That’s merely a reason to worry about particular, suspicious prizes.

I think the idea would be that awarding large prizes may affect judgments involving parties related tot he prize giver or with known adverse positions to the award giver. Judges (not Justices) may not accept awards that may cast doubt on neutrality or fairness. For reasons similar to limits on the organizations judges may be members of. Justices can do more or less whatever they want as there is no supervision of Justices. Anti-bribery statutes, which require quid pro quo would apply whatever the form or process of bribe.

J. Bogart: I can agree with that point, and it could be David Wallace’s point. But then the point is trivial, and his comments have suggested that his is a nontrivial point. Perhaps the thought is that it may have an impact on how some people (Trump’s supporters or right-leaners) view an upcoming judgment. This would make the point much less trivial.

Well, try this: suppose that I’m very pro-life (I’m not) and very rich (I’m not), and I announce that I’ve set up a foundation to give five prizes annually, of $20 million, to those five judges whose ideas on constitutional law most effectively support the right to life. And suppose later this year we get a radical SC overturning of Roe vs. Wade, on a 5-4 vote. And then suppose later that year that my foundation gives $20 million to the five majority judges in the ruling. Something would be profoundly wrong if that sequence of events were to happen, even if there was no actual prior agreement between my foundation and the SC judges.

You say there would be something profoundly wrong with it, but why should anyone agree? You simply assert it, giving no reason to agree (accept perhaps on an intuition about the example). But someone may say “what’s so wrong with it?”

I wasn’t really trying to argue for it. I’m trying to make the point to the (I suspect) large fraction of readers who agree with me that it’s wrong, that for that reason they should be uncomfortable about cash prizes to liberal judges too. If you’re fine with the pro-life thought experiment, our political-theory disagreements are too deep to plausibly reconcile in a blog comment thread.

It’s not that I’m fine with the thought experiment. It’s that I’m not moved in either direction because I’ve been given no compelling reason to think there’s something wrong or to think there’s nothing wrong? The experiment involves certain judgments that might (but might not) be accurately explained partly by a foundation’s announcement. This feature of the experiment might make us uncomfortable, but that’s neither the same as nor sufficient for being wrong . Apparently, then, our disagreements aren’t about political theory but about metanormative (or metaethical) theory.

If we’re disagreeing not only about political theory but about the classification of philosophical problems, then there’s even less hope for us to reconcile those differences in a blog comment thread 🙂

That’s something about which we agree! Perhaps soon we’ll disagree in person, with a hope of sorting things out.

Ah, but how would I know we were disagreeing in person?

I guess I’d have to give up anonymity first, which I’ll happily do as soon as I accept a job offer from USC 🙂

…or from the Uiversity of Pittsburgh.

It seems to me that the point is this: if judges know that having certain views, or reaching certain verdicts, will be rewarded with cash, they will subconsciously or consciously try to start holding those views or reaching those verdicts. This is a bad thing, insofar as it renders judges less objective. It’s also bad insofar as it undermines public trust in judges.

Now, whether it’s overall bad depends also on whether you think that people or causes with money are likely to reward positions/verdicts that undermine justice as you see it. If you’re a marxist, then I’m guessing you think this is quite likely, but you probably already see the justice system in a capitalistic context as set up to serve capital. If you’re a libertarian, you should see this as probably worse than it is good. Good, because rich people probably don’t like regulations, but worse, because businesses like putting regulations on smaller businesses to prevent competition. It’s harder for me to figure out whether this would be bad or good if you are on the social justice left.

Some of us might believe that an increase in judicial activism is a very good thing.

Until judicial activism you support is used as precedent for judicial activism you don’t support, I suppose.

No, even afterward.

Even afterward!? A principled stand in favor of judicial activism? I’m ready to hear it!

Someone might think: In some cases, judicial activism is the only means by which to deliver justice. And it is not always used in such cases. If so, an increase in judicial activism in those cases is very good. So, an increase is good.

I’m not prepared to deny any of the premises. For this reason, I withhold judgment on whether an increase is not good.

As stated, that argument is fallacious. Even if we grant that judicial activism is the only way to achieve justice in many cases, this is perfectly compatible with it being used in the majority of these cases to promote *injustice*. For instance, this could be the case if the other branches of government were in constant gridlock such that the judicial branch has to basically handle everything, but is almost wholly corrupt.

YAAGS: There’s nothing fallacious about the argument. Even if there is, you haven’t given any reason to think so. The fact that there is the compatibility you mention shows neither that the argument is invalid nor that it has a false premise. Maybe you think you’ve shown the conditional is false. But you haven’t because the consequent is not that ANY increase is very good. It is that an increase is very good. Which increase? One in which the activism is used to promote justice.

If your point is that an increase in judicial activism that specifically promotes justice and not injustice would be good then your point is rather trivial. The question is whether an increase in judicial activism in general is likely to be good. I rather doubt it. For no other reason than that judicial activism has a destabilizing effect on democracy. If most major legislative issues are decided by judges that are appointed for life by presidents, and the court can be stacked, this is likely going to cause political chaos where major decisions are overturned and rewritten every four years.

“… judicial activism has a destabilizing effect on democracy. ”

I think in fact, the opposite has been true. The Warren court, maybe the paradigm of judicial activism, protected and energized democracy rather than destabilizing it. By contrast, the current Court’s refusal to protect voting rights in Michigan, under cover of judicial restraint, could cause long term damage to democracy in America.

“Judicial activism” is ambiguous in this context. I was taking YAAGS to mean something like “overthrow of existing law on the basis of highly contestable Constitutional interpretation”: on that basis, Roe vs Wade counts as judicial activism, but so does the evisceration of the Voting Rights Act by the Rehnquist court, or their ruling that states have a right to opt out of Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion. (And so, hypothetically, would be a ruling that future-president Warren’s wealth tax was unconstitutional.) In each case, the Constitutional argument is *at best* debatable (I think often wholly contrived) and the result is that laws passed by bodies subject to fairly quick democratic checks are overridden with no recourse but to undergo the long slog of changing the courts… which I take it is the instability YAAGS has in mind.

Hm. I don’t *think* this is a terminological issue, but just to be sure: are you saying that my examples (Warren court, recent Michigan gerrymandering decision) don’t fit your definition of ‘judicial activism’, or that they do but that your examples outweigh mine? [I disagree with both of those.]

The latter (at least for the Warren court; not sure about anti-gerrymandering) though I was mostly doing YAAGS exegesis rather than advancing my own argument.

Yes, I was taking judicial activism to include any ruling that is arrived at in order to achieve a socioeconomic effect or the fulfillment of a more general conception of justice (misguided or not), and for which there aren’t really any sound legal arguments. I’m pretty sure this is what legal scholars mean by the phrase. But note that it doesn’t have a normative valence. Citizens United could be counted as judicial activism as well. Libertarians and social conservatives can also be judicial activists.

Judicial activism is inherently undemocratic all by itself. The decisions made by the judges simply cannot be considered a reflection of the will of the people. For instance, take marriage equality. There is simply no argument that the people elected Bill Clinton in order to appoint someone like RBG so they could mandate all states to recognize gay marriage twenty years later. The decision itself is blatant activism. (Not that I think that gay marriage is bad.) There is a good argument that states cannot provide marriage licenses *only* to straight couples. But the decision itself seems to claim that getting a marriage license from the state is some sort of natural right. The legal reasoning is very clearly just a convoluted post hoc justification for what the majority took to be the moral (rather than legal) conclusion.

Now, you may very well think that the decision rightly served the ends of justice in this case. (I’d agree.) But the problem with relying on the court to do these things is that the court itself can (and often does) reverse its own decisions. And it wouldn’t be that hard to do in the case of marriage equality because the legal reasoning in the original decision is so tortured. By the end of the Trump presidency we could very well see the decision reversed. Moreover, this mostly depends on when the sitting justices die or are forced to retire.All Trump has to do is get lucky. Actual legislation is much, much harder to overturn. But the more political parties rely on judicial activism the less incentive they have to actually compromise and craft laws together. Rather than convincing people to pass laws in their states allowing gay marriage, the dispute instead becomes an all-or-nothing battle to elect “our guy” because “theirs” will elect judges that will overturn past decisions. This is in fact what is happening. On paper, the president should not be able to overturn Roe v Wade. But if you rely on the SCOTUS for all of your civil rights and the presidency controls the balance of the SCOTUS then your civil rights will be up for grabs in every presidential election. This leads to political polarization and extremism. (As a corollary, if you think the electoral college is undemocratic it seems you must say that the SCOTUS is undemocratic a fortiori.)

“Judicial activism is inherently undemocratic all by itself.”

I think that’s a serious mistake. The example I gave, of the Warren court’s activism, was most definitely not. It protected and enhanced democracy. Almost every bit of its protection of voting rights and political speech was decried as ‘activist’ at the time. And it did rely on highly controversial, contestable interpretations of the Constitution.

Now compare the current ‘restrained’ decision by Roberts et al., to stay out of the ‘political’ question of gerrymandered redistricting. Deference to the state legislature was surely one of the most anti-democratic decisions in the history of the Supreme Court. I doubt you can find any cases that come even close to destabilizing democratic institutions as that one is doing.

I guess you could just define ‘activism’ in such a way that decisions protecting democracy simply don’t count as ‘activist’. (There isn’t any one way that legal scholars use the term; it’s all over the map and has been since I guess Arthur Schlesinger.)

“Democratic” and “protective of democracy” aren’t synonyms. If 98% of the population vote “yes” in the “shall we abolish democracy?” referendum and the courts block its implementation, that’s plausibly an undemocratic action that protects democracy.

No, judgments promoting democracy still count as activism if they don’t have around legal basis in my book. The problem is that judicial activism is *proceedurally* anti-democratic, not that it always promotes anti-democratic policies. The problem is that activist decisions can’t be considered the result of the will of the people in any meaningful sense. Non-activist rulings are a result of the will of the people because they merely interpret the law as it currently exists, and the laws themselves were passed by elected representatives.

In addition to David Wallace’s example, consider that a benevolent monarch could also make pro-democratic decisions by decreeing that new laws in lesser fiefdoms must pass a majority vote by the subjects. That a benevolent monarch could do such a thing does not mean that monarchies are democratic. The obvious worry in this case is that the monarch can change her mind or may be replaced by an anti-democratic successor. This is why you want to have the laws of the nation written, passed, and revoked by elected representatives. Reliance upon activist decisions by the SCOTUS is better than reliance upon the good will of a monarch, but it ultimately creates similar problems.

DW:

‘”Democratic” and “protective of democracy” aren’t synonyms. If 98% of the population vote “yes” in the “shall we abolish democracy?” referendum and the courts block its implementation, that’s plausibly an undemocratic action that protects democracy.’

Well, maybe this is terminological after all. But, Yaags wrote that judicial activism *destabilizes* democracy. So I was showing why it (often) doesn’t. It seems like you are now changing the subject.

Yaags:

“Non-activist rulings are a result of the will of the people because they merely interpret the law as it currently exists, and the laws themselves were passed by elected representatives.”

To be clear: you are saying that before the Warren court protected voting rights, the laws that deprived black people of their voting rights in Mississippi expressed the will of the people?

I disagree. Should I explain why?

“That a benevolent monarch could do such a thing does not mean that monarchies are democratic.”

No. But if a benevolent monarch *does* usually do such things, say in the context of a constitutional monarchy, I think it’s a mistake to complain that they are destabilizing democracy.

Reliance upon the monarch’s benevolence doesn’t lead to a stable democracy. For similar reasons, over-reliance on activist decisions by the SCOTUS destabilizes democracy insofar as the decisions can all be overturned if the opposite party gets lucky and has a bunch of justices die on their watch. By then you might wish that the problem had been solved through actual legislation, since your only options will be to either wait possibly more than a decade for more justices to die or pack the court.

So the analogy is:

Democracy in Mississippi would have been in better shape if the Supreme Court had allowed the white racists to continue to rig the electoral districts to ensure that black people had less voting power.

Yeah, no, I don’t think so.

Michigan will now have a more stable democracy, since the party in power will be able to rig the electoral districts to favor their candidates?

The will of the people, as expressed in the vote that gives the white people (or Republicans, in the current case) more votes. Rousseau is spinning in his grave.

@Jamie: “Changing the subject” overstates my level of engagement in this bit of the thread. I think you and YAAGS are slightly talking past each other, and my small interventions were (probably misguidedly) intended to ameliorate that.

I don’t really want to get tangled up in the main issue (though I will say that the specific case of judicial activism *on the voting system itself* is interesting, and I hadn’t given it enough thought – so, thanks.)

Jaime… an analogy generally involves a comparison between two things. In the situation you describe where the SCOTUS renders a judgment preserving the voting rights of minorities, the case I think would be better is one in which congress passed a voting rights amendment explicitly prohibiting the rigging of electoral districts, rather than one in which nothing happened and racists just continued rigging districts. Nothing in any of what I said implies that I would just want nothing to happen. An unstable solution is preferable to no solution, but a stable solution is preferable to an unstable one. (And, again, this is all on the assumption that there wasn’t already a sound constitutional argument against such practice, or else it doesn’t even count as a case of judicial activism.) My main reason is that it is harder to overturn a law explicitly prohibiting such things than for a later more conservative version of the court to overturn the decision, which can happen out of the blue and cause chaos.

Maybe an extreme case would help illustrate the point. Suppose the SCOTUS provided a judgment completely out of the blue that healthcare is a basic human right and that the federal government must provide a public option. You really don’t think that might lead to just a wee bit of political chaos? You don’t think the republicans would flip out and attempt to pack the court to repeal the decision? You really think that this would be equal in value or preferable to the American people voting in a party that campaigned on a well-crafted public option plan? Imagine if the republicans had control when the decision came down. You don’t think they would try to sabotage the bill so that no one buys into it?

Reflecting further on this, it *might* be that ethics rules for federal judges required RBG to donate the prize money rather than keep it. (She’s actually donating it, but I originally assumed that was just good judgement on her part.) If so, it would obviate most of my concerns. Anyone know?

i believe it was a requirement, though i’m not 100% certain. there was certainly a lengthy review period by a judicial ethics board at the supreme court.

Thanks, David: that’s reassuring.

If it is easily at hand, can you point me to information on the ethics panel review? If not easily at hand, never mind. Thanks.

While the general Judicial Code of Conduct restricts actions that could be seen as impinging the impartiality of judges, this code of conduct _does not_ apply to Supreme Court justices. Some brief discussion is here: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/LSB10255.pdf (Supreme Court Justices can be impeached and removed from office, but the standards for that, perhaps even more than for impeachment of the president, are less than 100% clear.) There are rules on the acceptance of gifts by federal employees that apply to judges, and perhaps to the Supreme Court justices, but the don’t seem to obviously include cases like this one. See here, for the text: https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/5/7353 The judicial code of conduct is not completely clear, to my mind, as to whether it would rule out a gift like this to most judges, but again, it doesn’t apply to the Supreme Court. The text can be found here: https://www.uscourts.gov/sites/default/files/code_of_conduct_for_united_states_judges_effective_march_12_2019.pdf

Many Supreme Court justices have received valuable gifts and awards in the past, and in many cases have kept them. Ginsburg seems to be of above average diligence in not keeping these prizes, though of course the ability to give away money to others is itself a power (as Aristotle noted long ago.) For some examples, see here: https://www.acslaw.org/expertforum/supreme-court-justices-accept-substantial-gifts/

So, while I’m not an expert on judicial ethics, my impression is that there was no legal requirement that Ginsburg not personally accept the prize money, but that it was a good policy to do so. It would have perhaps been an even better policy to not accept the prize at all, but perhaps that would push things too far.

Ginsburg’s accomplishments before she joined the Supreme Court, in terms of legal innovation and victories in the areas of gender equality and women’s rights, are probably just as important if not more important than anything she’s done on the Court. (This impression derives partly from the movie about her, not the documentary but the Hollywood version, which I think is reasonably accurate albeit dramatized.) So my guess would be that she’s receiving this prize as much if not more for what she did before she joined the Court as for what she’s done on the Court.

While I am partial in theory to the overall priority of arguments about justice and equality and the like, the last few years have pragmatically awoken me from that dogmatic slumber. We are talking about a million dollars here, where in fact billions upon billions have pushed this country, and the judiciary along with it, to please that self-satisfying power of the purse, allied with the purchased powers of social and much commercial media, well over any such supposed power as the power of reason or argument. I was hoping that the brazenness of the abuse of such financial power as exhibited and Tweeted hourly in Washington would shock the country to returning to the confines of something dimly reflective of the examined life. However, I’m afraid we collectively no longer can muster enough virtue to resist the manipulative power of the Almighty George Washington dollar–surely as profound an irony as a masterful tragedian could write. This thread is about principles that no longer have real power in the face of what constitutes by comparison the 1 George Washington RBG got out of the 1000 of each of a multi-billionaires fortune.

Awarding a swanky philosophical $1m prize to someone who (a) is not a philosopher and (b) is morally (and prudentially, maybe even legally) obliged to donate the money elsewhere?

Jesus wept.

What’s the significance of it having to be given away? It’s a personal award (i.e., not funding for research, although I think Nussbaum used some of it that way) and all of the philosophers who have won it previously are wealthy enough that it’s unlikely to be of life-changing significance to them. I assume the $1M is a symbolic signifier of the prize’s importance more than anything else.

Well, if they’re happy with the money only symbolising the importance of the prize, Plato gets my vote for 2020.

The comment thread seems to be too extended to directly reply, but I wanted to note this remark by Jamie about court decisions that are said to be a product of “judicial activism”: and for which there aren’t really any sound legal arguments

This is said to apply to both Roe v Wade and Citizens United. The problem with this account is that in both of those cases there are perfectly sound legal arguments, and they can be found in the majority opinions. Now, they were not _clearly_ determined by precedent, or by the mere texts of the constitution or the relevant statutes. But – that’s not needed for a legal argument to be sound. (Legal arguments are not like deductive logic, and it’s just a mistake to think they are – for many reasons, but most importantly, because reasoning by analogy is completely sound method of legal argument.) Even in the case of Roe, it builds quite naturally off of a series of cases coming before it. I’m not crazy about the outcome of Citizens United (especially in its practical impact) and don’t think it’s strictly implied by the legal materials, but neither was the opposite conclusion, and it’s a plausible enough reading of relevant decisions and the constitution. Now, there are some cases that both don’t fit with the text of the constitution well at all, and that don’t follow a trend of decisions. The clearest example would be Shelby County v Holder. The over-ruling of the medicare expansion aspect of the ACA in NFIB v Sebelius is also an example, although less obvious than Shelby County. But, for several of the cases mentioned as examples of “judicial activism”, just just not at all true that there are “no sound legal arguments” for the conclusion. Does this mean they were not examples of judicial activism? I’m not sure I’d want to say that, but if we want to include them, we need to think of a different definition of “judicial activism”.