Collingwood and the Contintental – Analytic Divide

“Possibly—the great schism would never have set in at all, had RG Collingwood, one of the most remarkable, open and eclectic minds of the 20th century, not died prematurely in 1943.”

That’s philosopher Ray Monk (emeritus at Southhampton) writing in Prospect Magazine about the analytic-Continental divide in philosophy. According to Monk, R.G. Collingwood’s early death led to his being replaced as Waynflete Professor of Metaphysics at Oxford by Gilbert Ryle, a “deep but curiously narrow thinker” who “used this lofty position to remake the British discipline in his own image.”

Monk notes that “no one has come up with a satisfactory way of drawing the line” between analytic and Continental philosophy. He adds:

Broadly speaking, however, one can say that the continental school has its roots in the phenomenology of Edmund Husserl, and encompasses a range of diverse traditions, including the existentialism of Jean-Paul Sartre, the structuralism of Ferdinand de Saussure, the postmodernism of Jean-François Lyotard and the deconstructionism of Jacques Derrida. The analytic school, meanwhile, has its roots in the work of Gottlob Frege, Bertrand Russell and Ludwig Wittgenstein and has been until fairly recently much more narrowly focused, concentrating mainly on logic and language. The divide is certainly strange and arguably arbitrary, but it none the less cut deep. For decades, it was possible to do a degree in philosophy at a major university in the UK or the US without once encountering any of the continental philosophers mentioned. This splintering of the discipline would have appalled many philosophical greats from earlier ages.

As Bill Blattner remarks, “The so-called Continental-analytic division within philosophy is not a philosophical distinction; it’s a sociological one. It is the product of historical accident.”

Monk fills us in on one part of the story of this “historical accident.” In 1928, Ryle reviewed Heidegger’s Being and Time “with respect (even if with robust dissent)”. But over the next 30 years, Ryle became increasingly hostile towards the kinds of philosophy that came to be called “Continental.”

Things came to a head in 1958, at Royaumont in France. A conference had been held here to connect a group of continental philosophers (mostly French phenomenologists) and their Oxford counterparts, with the aim of bridging the gap between their two schools. But, as if determined instead to reinforce it, Ryle gave a paper called “Phenomenology versus ‘The Concept of Mind,’” the latter being the title of his most famous book. That “versus” captured his pugnacious mood. In this paper, Ryle outlined what he regarded as the superiority of British (“Anglo-Saxon,” as he put it) analytic philosophers over their continental counterparts, and dismissed Husserl’s phenomenology as an attempt to “puff philosophy up into the Science of the sciences.” British philosophers were not tempted to such delusions of grandeur, he suggested, because of the Oxbridge rituals of High Table: “I guess that our thinkers have been immunised against the idea of philosophy as the Mistress Science by the fact that their daily lives in Cambridge and Oxford colleges have kept them in personal contact with real scientists. Claims to Führership vanish when postprandial joking begins. Husserl wrote as if he had never met a scientist—or a joke.”

Nothing bridges gaps like comparisons to Hitler.

Ryle believed “that he and his colleagues were doing philosophy in a way that broke sharply both with philosophers of the past, and with those from other countries. Their way was the better way, and philosophy from earlier times and other places wasn’t really worth bothering with.” His position afforded him great power to shape philosophy in Britain:

As the editor of Mind, then as now the British discipline’s most prestigious journal, from 1947 to 1971, Ryle could strongly influence, and sometimes dictate, what subjects British philosophers discussed and how they discussed them. Moreover, as the accepted leader of philosophy at Oxford, he was able to exert a personal influence on a good proportion of the philosophers who staffed the philosophy departments in the fast-growing number of post-war universities.

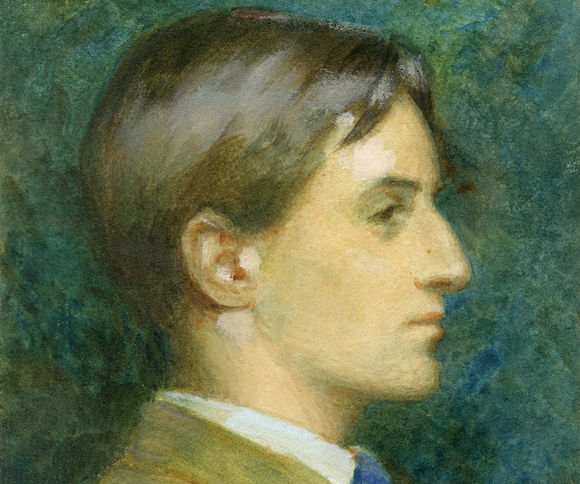

Ryle’s style contrasted to the broad curiosity of his predecessor, Collingwood, whose “personality, attitudes and approach to philosophy can be best understood as the opposite of Ryle’s.”

One can see from Monk’s description of Collingwood’s approach to philosophy how it differed from that of early analytics:

To understand a work of art, a person, a historical epoch or a religion is, so to speak, to “get inside its mind,” to see the world through the eyes of people using a different set of presuppositions to our own. If we try to understand others using only our own presuppositions, we will always fail. Historical understanding, for example, “is the attempt to discover the corresponding presuppositions of other peoples and other times.”… For Collingwood then, unlike philosophers in the Ryle mould, imagination and empathy play a crucial role in understanding. And here, perhaps, we have a tantalising glimpse of how British philosophy might have developed differently had Collingwood not died so early and if he had had the sort of influence that Ryle acquired. Certainly, it is impossible to imagine such an open and restlessly questioning mind giving the sort of dismissive paper that Ryle did at Royaumont.

Monk provides quite a bit more detail in the article, making plausible his claim that “the question of what course post-war philosophy in Britain might have taken if Collingwood had not succumbed to a series of strokes at this relatively early age must rank as one of the great ‘what ifs’ of intellectual history.” You can read the whole thing here.

Related: How Journal Capture Led to the Dominance of Analytic Philosophy in the U.S., Quality Control, Methodological Bias, and Persistent Disagreement in Philosophy, The NSF and the Rise of Value-Free Philosophies of Science

Monk makes a good case that Ryle’s curt dismissal of Continental philosophy was more influential than often thought. It may even have served as prototype for later dismissals on racial and gender grounds. I am not sure, however, that Husserl was as important to Continental philosophy as Monk (along with many others) thinks. If you look at the post-Hegelian philosophers, they all accept, in practice at least, two premises: (a) everything philosophers can talk about is in time, i.e. comes to e and passes away; and (b) philosophers must incorporate this insight into all their discussions. Analytical philosophers, by contrast, tend either to view the “laws of logic” as time-independent, or to claim that they can be treated that way (Quine).

Both approaches have problems, which I will not sort out here. The point is, Husserl, with his quest for “apodeictic” and “eidetic” structures of consciousness, is pretty clearly on the analytical side.

While Husserl’s work has a lot of aspects that would fit him more comfortably on the analytic side (see Føllesdal and others comparative work on Husserl and Frege), I wouldn’t underestimate his “continental” influence. For example one of the core aforementioned structures of consciousness is temporal synthesis. Also his late work in Crisis, has a historical bent, not unlike Hegel.

Check out an article in Religious Studies out of Cambridge (2016) titled “A Metaphysics of Belief: A Wittgenstein and Collingwood Convergence”, by James E. Gilman

But something could come about as result of a “historical accident” and still amount to a substantive philosophical distinction. Right?

I’m not sure why many people want to insist that the divide is not philosophically significant. It often has a tone that it’s a norm of collegiality to insist that the divide is not philosophically significant. Is it too hard to be good colleagues while thinking that we have very deep disagreements about the subject matter of philosophy and its method?

I’m happy to discover any new scholarship on Collingwood, especially any that contrasts him favorably to Ryle.

But there are some prima facie difficulties with the thesis:

1. Collingwood was not the towering public figure that Ryle became. He was very private and had long resigned to being a bit of an outcast (think of all the remarks about Cook Wilson in his Autobiography – this was not a person who wanted to dictate professional norms as Ryle or Quine did).

2. More importantly, 1943 is an extremely late date in the divide. While Ryle became important, I don’t see how this subject (the social division between continental and anglophone philosophies) can be approached without beginning at least in 1914. The reaction to the invasion of Belgium led to worries about German philosophy. So much against what became called continental philosophy was already written by the end of the (first) war, so many professional procedures and tendencies already changed, and so much public perception altered that it’s hard for me to entertain seriously the thought that had Collingwood remained alive into the 1950’s or 1960’s that anything in this regard could’ve been different.

3. While Collingwood’s theory of historical understanding would likely make him a more congenial correspondent to the subsequent French philosophers mentioned here, there would still be significant divides between his approach to the discipline and those that became associated with the term continental.

Postscript: while my comments do endorse the view that there was a divide, this is a merely historical matter. The divide in question concerns the tendencies of professional philosophy in England/ U.S. as opposed to Germany and France from about 1914 until about 1990. It’s not a global thing, only sometimes a deep philosophical thing, and in any case a past thing.

“The divide in question concerns the tendencies of professional philosophy in England/ U.S. as opposed to Germany and France from about 1914 until about 1990. It’s not a global thing, only sometimes a deep philosophical thing, and in any case a past thing.”

Was the divide really this geographically-based? Even before the Vienna Circle, Berlin Group, and Polish logicians fled the continent during World War 2? The European philosophers in those groups seem to me to have more in common with Russell, Ramsey, and Quine than does Ryle (or Austen or Wittgenstein or Dewey, for that matter). (Moore is a different story.) Nor do Neo-Kantians like Cassirer fit into the Husserl-Heidegger-Sartre tradition, which isn’t to say they do belong squarely in the “analytic” tradition; rather, there doesn’t seem to be a pre-World-War-2 German/French tendency in philosophy.

Or, as I would say–pre-McCarthy Era tendency

I said WW2 because nearly all the thinkers who were in continental Europe in the mid-1930s and who were influential in analytic philosophy fled and ended up in English-speaking countries (Carnap, Tarski, Reichenbach, Goedel, Hempel, Neurath, Feigl, Frank, Bergmann, and Popper). This completely changed philosophy on the continent, where philosophy students lost exceptional philosophical mentors. The McCarthy era may have played a role in the rise of analytic philosophy in the US; my point is about the role the Nazi era played in the near disappearance of, for lack of a better term, Wissenschaftslogik from the continent.

The exodus of scientific philosophers out of Europe in the lead-up to WW2 actually throws some light on the anti-scientific currents in continental thought that Ryle alluded to. There’s currently a kind of dogmatic ecumenicalism about the a/c divide that will see Ryle’s comments as narrow-minded, arrogant, etc. But I doubt it’s really controversial that such currents exist; the run through Heidegger’s opposition to logic, the Frankfurt school’s critique of the Enlightenment and of instrumental rationality, and the French existentialists’ embrace of pseudo-scientific psychoanalytic and Marxist ideas. (To point to these *currents* is not, of course, to suggest that all continental philosophers are swept up in them.)

Ryle was probably wrong about the cause, though. The Vienna Circle, Berlin group, and Warsaw group thinkers were at least as engaged with relevant sciences as the Oxford ordinary language philosophers. So the central European university systems weren’t the problem. One might speculate, though, that with Carnap, Reichenbach, Tarski, Goedel, Popper, etc. in the English-speaking world, the absence of scientific philosophy in Germany and Austria might have allowed the anti-science currents to grow by leaving them relatively unopposed in those, at the time, philosophically influential countries.

With respect to your reference to “pseudo-scientific psychoanalytic and Marxist ideas”: If I were banished to the proverbial desert island, I’d rather take Marx and Freud with me than the collected works of Carnap. This is just one non-philosopher’s perhaps “pseudo-scientific” preference…

If I were on a desert island, I’d probably prefer fiction as well.

I am trying to figure out the sense in which you think Heidegger “opposed logic.” If you are thinking of Carnap’s supposed debunking, the issue was not the legitimacy of logic, but whether one can reduce phenomenological observations to linguistic or logical confusion. It is also worth noting that Merleau-Ponty’s work on perception is at least as versed in the then current empirical research as any contemporary philosophical work in the field. My point is only about the phenomenological tradition, not, e.g., post-modernism, of which I remain blessedly silent.

Thanks for the reply. What you say is consistent with what appears to be Monk’s motivation. Just as you can pick German or Austrian philosophers who more closely resemble the analytic philosophers, so you can pick English philosophers who more closely resemble the continentals. Hence this was a discussion about Collingwood.

A historical generalization will always have counterexamples if the intent is to express ‘All English philosophers were of Type A’. But that is not the basis for any analysis of a divide in this case. Monk’s whole point, it seems, touches on geography: it’s about certain English philosophers in contrast to certain French ones. So Monk cites some episodes with the suggestion that these are illustrative of larger historical tendencies, and if you analyzed the institutions (examined all the issues of Mind from 1943 – 1965, contrasted them with French journals, looked at the major academic hires, presses, etc.) I think that would come out clearly. There were cultural differences spilling into philosophy, and cultural differences among philosophers. The reality of such differences is not disproved by noting that there were cultural mixtures of various types, any more than the existence of mixed race people should suggest that there are no racial divides.

Now you make one important historical point that I agree with: there’s no French/ German thing in the beginning of the era I referred to. That comes later. The analytic/ continental divide at least started as an Anglo-Germanic issue, with the French forming a third stream later coupled with the Germans. You won’t find treatises written in 1915 about why the study of French philosophy is dangerous, but you will find them about the Germans. Part of the story, I suppose, is that it’s only later that the French start allying with the Germans in philosophy. (Leaving out the Poles only emphasizes, in my eyes, that this whole thing is a regional dispute with perhaps global political consequences, but not itself a global dispute)

As for the observation that what became ‘analytic philosophy’ (quotes to demarcate a different sense) in America later was as much influenced by assorted Austrians and Poles as by Russell, Moore, and Ryle only raises additional questions, it doesn’t negate the core thesis, viz., that there was an historically specific divide in the philosophy profession associated with the geographic boundaries among England, Germany, and France, which later continued in the profession long after the political lines had shifted.

The picture I mean to portray in outline is actually Russell’s picture. He was very clear about the fact, in his later years at least, that the biggest factor in the institutional development of analytic philosophy was the anti-German sentiment that arose in August 1914. To my eyes Thomas Akehurst has exhaustively made the historical case here, and he (so far as I can tell) meant for it to cohere throughout with the observations of Russell, Ayer, and Ryle. (the short version of his argument: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1016/j.histeuroideas.2008.03.002)

But it is worth asking him, and anyone else, what the anti-French thing has to do with it. The attitude towards the French expressed by Ryle seems to me largely aesthetic and shouldn’t easily be clustered with the Anglo-German divide. The latter was more philosophical: the Germans believed in what we today call social wholes, and they didn’t seem to reason in a manner reflecting the Frege-Russell logic (the fact that many Neo-Kantians also rejected social wholes only makes your initial point, but in Germany this was a domestic divide that happened to reflect a regional divide, which is no big deal). But the British attitude towards the French is not explained easily as part of a larger tendency to reject something called ‘continental philosophy’, unless by then the British started to lump Sartre and friends in with Hegel, Marx, and Nietzsche, who were the real enemies.

“As for the observation that what became ‘analytic philosophy’ (quotes to demarcate a different sense) in America later was as much influenced by assorted Austrians and Poles as by Russell, Moore, and Ryle only raises additional questions, it doesn’t negate the core thesis, viz., that there was an historically specific divide in the philosophy profession associated with the geographic boundaries among England, Germany, and France, which later continued in the profession long after the political lines had shifted.”

Okay, I see your point better now. Also, I hadn’t been aware of the early analytic philosophers’ views on continental romantic philosophy.

Maybe I read too much into your phrases “tendencies of professional philosophy.” I read them as suggesting there was a single philosophical tendency. That’s what I meant to deny.

I may also have invested your claim the geographical boundaries are *associated with* the division more or a different kind of causal importance than you intended. One possibility that’s consistent with everything either of us has said is that there were various kinds of philosophical tendencies in various countries, there were divisions between these various tendencies, and one such division became the analytic/continental divide. On one version of this view, geography is incidental–it’s the differing tendencies that are causally efficacious. Had the Berlin Group taken over academic philosophy in Germany after WW2, for example, we might have ended up with much the same a/c division. (I’m agnostic about such hypotheses.)

One other way of cashing out the association between geography and the a/c divide: German and British cultures contributed, causally, to the existence of the philosophical circles that whose mutual separation became the a/c divide. Akehurst sometimes seems to read the British analytic philosophers’ take on Germany as in this neighborhood.

Again, I’m agnostic about this hypothesis. But I would want to emphasize that a given national culture can be expected to contribute to many heterogeneous sub-cultures. So German culture could have contributed, causally, to the circles mentioned above and to the philosophical circles that were so consonant with British philosophy.

Thank you Wissenscaftslogiker and Kevin Joseph Harrelson for the fascinating exchange. I have long been puzzled by how we talk of ‘analytics’ and ‘continentals’ when both factions draw from the same sources (and still teach them: Plato through to Kant).

Could a rapprochement be in order? If it can be shown that, at least in part, the division has emerged not for philosophical reasons but contingent ones, determined by historical circumstance, then perhaps the animosity between the two camps might be assuaged?

It struck me as a graduate student, with no flag in either camp, that the division was ridiculous; that we were both, in the public view, arguing for ridiculous things, and that we might be better saying ‘You think one way, I another, but we are both branches from the same root’.

Your historical analysis fills me with joy because it demonstrates my point evidentially:

Thanks Chris.

My view is that it’s senseless to appropriate the divisions of mid-twentieth-century philosophy. But maybe we’re in a minority. Witness the comment by The Divide is Real, which was the most appreciated in this thread!! I’m among those who liked the comment, for this reason:

Anglophone academies after about 1970 had various subcultures, some of which taught philosophy exclusively as an appreciation of a certain European canon extending from Heidegger and others. When people learn philosophy that way and then get jobs in departments with mainstream anglophone philosophers, they *feel* a divide, and that’s a real thing. And so when others diminish it or say they shouldn’t feel the divide it seems to them, understandably, disrespectful.

Should there be a rapprochement? I don’t know, because it’s hard to argue that there shouldn’t be different subcultures in a discipline, even where it leads to misunderstandings and occasions institutional factions. It’s hard for me to see it all as a big deal. So what, you learned a different academic style and canon? The only thing I insist on is that analytic vs continental does not have much legs left. It’s a division from the day before yesterday, even though it still impacts the professional prospects of a few aspirant professors.

I would like to add another important figure who, had he not died in 1945, would have prevented this divide from playing itself out the way it did: Ernst Cassirer.

On Dr. McCumber’s take on Husserl: his mature project is indeed an eidetic science of transcendental subjectivity, but in his late phase, he also recognized the history and historicity of constitution. So the Husserl of the Logical Investigations (who is typically the only one analytic philosophers know and read) would fall into the Analytic camp; the later Husserl (as of the 20s) clearly into the continental camp.

Dear Sebastian Luft: Thanks for calling attention to Cassirer; you’re right. Michael Friedman has done important work on this.

As to Husserl, your key word above is “also” (“he also recognized…”). Continental philosophers in general do not countenance any claims about time-independent entities: none. This is a substantive philosophical difference between analysts and continentals. The late Husserl, as I understand him (see Cartesian Meditations), assigned some importance to history but believed that the eidetic dimension, so to speak, existed and was worthy of investigation.

Dear John McCumber, you are right about Husserl’s prioritizing eidetic over factual. However, he also has a project of “phenomenological metaphysics,” which is about the “factum world” and is what he calls “second philosophy.” This isn’t really worked out but at least it’s there as something to be done (as so many of his ideas).

As for Cassirer, Massimo Ferrari and I organized a conference in 2018 called “Cassirer’s Children.” The proceedings will appear in 2021 in the Journal of Transcendental Philosophy.