Graduate Students on Diversity and Inclusivity in Philosophy (guest post by Carolyn Dicey Jennings)

The following is a guest post* by Carolyn Dicey Jennings, associate professor of philosophy and cognitive science at University of California, Merced, and creator of Academic Placement Data and Analysis (APDA).

Graduate Students on Diversity and Inclusivity in Philosophy

by Carolyn Dicey Jennings

Many philosophers recognize that the field has a “gender problem,” and maybe even a “race problem,” but I have come to believe that it has a diversity problem. This is because I helped lead a survey that revealed problems for women, those who identify as non-binary, racial and ethnic minorities, those from a low socioeconomic background, those with military or veteran status, LGBTQ philosophers, and those with disabilities. Graduate students from these backgrounds are underrepresented, find themselves less comfortable in philosophy, find philosophy less welcoming, are less likely to recommend their graduate program, are less satisfied with the research preparation, teaching preparation, and financial support of their graduate program, and are less interested in an academic career. This is a problem not only for reasons of equity and inclusion in philosophy, but also because diversity improves collective performance—philosophy is worse off as an academic discipline so long as it has this diversity problem. Fortunately, the participants in our survey provided some insight on how we might move forward, especially favoring increased representation from these groups among faculty and graduate students, at conferences and workshops, on syllabi, and in publications.

Some background: In 2018 three groups came together to run a survey on diversity and inclusivity: the Graduate Student Council of the APA, the Data Task Force of the APA, and the Academic Placement Data and Analysis team. We provided a preliminary report to the APA in 2018, and this summer I wrote and delivered the final report, available here. That report is around 12,500 words, so I thought it would be useful to provide a summary of some of the findings in this blog post.

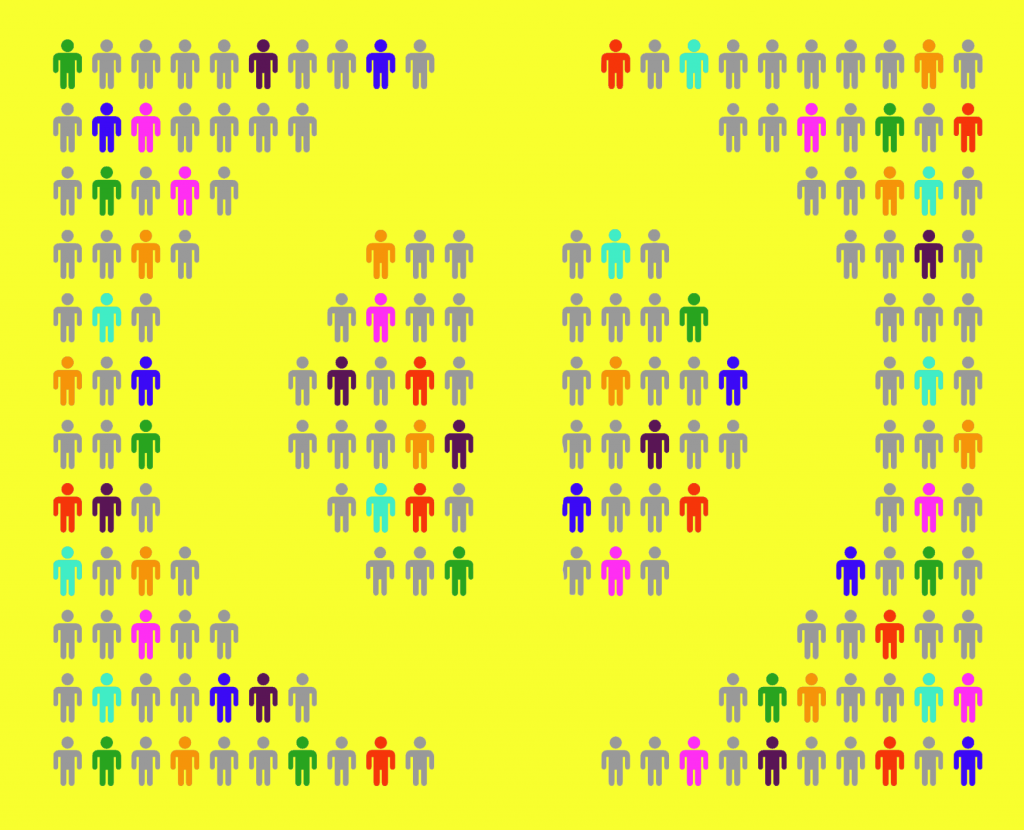

To start, I made a few simple infographics that help to see the problem of underrepresentation for three of the groups mentioned above: women, racial and ethnic minorities, and those from a low socioeconomic background:

As is illustrated by these charts, philosophy does not only have a smaller proportion of graduate students from these groups than the general population, but it also compares poorly to doctoral students overall. (We also found this to be true for veterans or members of the military.) As we know, the obsession with “genius” is correlated with a lower proportion of women and Black/African Americans across disciplines, and philosophy is especially obsessed with genius. Yet, philosophy also has a lower proportion of Asians than other doctoral programs, which cannot be explained this way. Further, I don’t know of a stereotype or bias regarding innate intelligence when it comes to socioeconomic status. It is hard for me to imagine a shared characteristic between these many different groups that is more significant than the fact that they have been historically marginalized.

So it is worth asking: what is it about philosophy that it includes fewer of those from historically marginalized groups? Is there anything we can do to fix the problem? I don’t have an answer to the first of these questions, but there have been numerous hypotheses on gender and race in philosophy that may apply to issues of diversity, more generally (see, e.g., Antony 2012; Cherry & Schwitzgebel 2016; Thompson 2017). A new possibility I have considered, but haven’t tested, is that the sheer variety of topics and methods in philosophy leads philosophers to seek demographic unity in order to maintain a sense of cohesion. If that’s right, we might expect programs with a narrower focus to be better platforms for inclusivity. I would like to explore this idea further, and I welcome feedback from others on how to do so. Clearly, more work needs to be done to determine the source(s) of this problem, but if this is one of the causal factors then a direct focus on community building will be key.

On the second question, our participants provided many good ideas. The most popular idea is to simply increase the diversity of the discipline, wherever possible. Other ideas include training and behavior, institutional support, and funding. Take, for example, these two public comments on training and behavior (emphasis mine):

I think this survey is a great start. Many of the steps the APA has taken under the leadership of Amy Ferrer have been excellent. I think the biggest challenges lie in the [graduate] programs themselves. It might help if the APA could offer training and certificates in areas of professional conduct for graduate students and faculty. Also, I think the APA should have stronger connections with Deans and Administrators in graduate education. This way if a graduate student reported something, the university could take appropriate action. Many students from underrepresented groups endure the discrimination and hostility in silence. They need to feel they have a place to go. For example, I was the victim of an assault by a visiting faculty member at a conference at my university. After graduation, I finally told my adviser. She told me she wished I had told her sooner. Title IX has helped in this area, but much work still needs to be done in PhD programs.

More and better funding for members of underrepresented groups (including class). More climate training sessions held within individual departments. Changes to core philosophical curriculum to include more areas outside of LEMM and Ethics (Feminism, Race, Indigenous Philosophy, Disability Studies, East Asian/South Asian Philosophy, Africana Philosophy, etc) or even using articles that talk about core philosophical concepts with reference to more diverse examples and cases. Implementing hand/finger etiquette in Q&A sessions (where a hand is a new question and a finger is a followup on the question originally asked). Bystander training for chairs at conference sessions so the chairs can intervene in instances of disrespect and abuse—they could also be trained to prioritize certain identities of interlocutors if the Q&A is dominated by white men. This could be communicated through an advice to chairs pamphlet. Having diversity coordinators/advisors (or designated allies) within departments who can aid underrepresented graduate students if they are experiencing problems throughout their degree. Open conversations about depression and mental illness in graduate programs in philosophy—perhaps running mental health seminars with the help of university health programmes.

The comments from participants in our survey contain a wealth of ideas, and the report is just a start to summarizing them. (I will also be providing public comments in my weekly blog posts on individual programs, here.) Beyond reading and digesting the report, my hope is that philosophy programs will take a hard look at these multiple dimensions of diversity and assess the measures they are taking to address them. Clearly, we all need to do much better to ensure the success of philosophy as a discipline.

I agree that we should try to “simply increase the diversity of the discipline, wherever possible,” at least for gender and race, but here socioeconomic diversity strikes me as different. It’s just irresponsible to push students to do MAs and PhDs if they can’t afford it — which they often can’t, if the program isn’t funded, the stipend is low, or the market is weak.

More generally, we shouldn’t just ask what diverse students can do for philosophy; we should ask what we can do for them. They aren’t just multi-color butts in seats. They’re rational people with their own desires and beliefs, as this post nicely acknowledges towards the end in its calls for protection against discrimination and open dialogue about mental health, both of which would make academic life more attractive.

I am not sure that philosophy is more economically precarious than other doctoral disciplines. We know it isn’t true at the undergraduate level. Worth exploring. In any case, a small step I have taken on this, inspired by Eric Schwitzgebel, is to use different examples in my writing. I noticed that the literature on skill often uses the examples of tennis, piano, violin, ballet, etc.; in my most recent article with Alex Dayer we used the example of a popular, free phone game, Smash Hit. If we think and talk about philosophy as for people of any socioeconomic class, I think that would help.

I didn’t say that philosophy is unusually risky. My point was that poor students might have good reasons not to spend 6 years training to become professional philosophers, and so we shouldn’t assume that proportional representation is a good goal. It’s good *for us*, but we aren’t the only ones with interests at stake.

That said, I think it’s great that you’re using examples that aren’t just rich people things. “Philosophy is for everyone” is a wonderful message.

Yes, I thought that was a good point. It is just that philosophy is underrepresented relative to other doctoral programs, too. If philosophy is not worse off than these other disciplines in terms of economic prospects, then this shouldn’t be a factor.

I think we might be talking past each other a bit!

I was responding to the suggestion that we “increase diversity wherever possible.” My point was: we should think about what’s best for our students, not just what’s best for us. (Though of course we should do everything we can to make our programs fair, safe, and beneficial to students — totally agree with Dan Greco’s suggestions below.)

It sounds like you are responding to a nearby idea — that financial concerns *explain* why poor students are underrepresented in philosophy (relative to other fields). I didn’t mean to endorse that explanation. I was just making a moral point. We are responsible to our students, not just to the field, and we should bear this in mind when give our students advice about graduate school.

(Hope I don’t sound too negative, by the way. The post was interesting, and I loved the visuals!)

No worries! I understood your point. It is an important and good one. I am just not sure that we should give differential support for those from a low SES background here, focusing our encouragement on women and racial/ethnic minorities. (A possible way of reading your first post, even if not what you intended.) That would depend, I think, on the explanation of why those from low SES are even less well represented in philosophy than in doctoral programs overall. If because philosophy seems like a bad economic choice, we may want to see if that is true and correct the error if not. If because of harmful cultural norms that lead to hostile treatment, we should correct that. In the meantime, encouragement might be just what people from this group need. More substantial change would be better, but even small acts can improve the discipline for some. I am guessing you agree with that, too, but I am drawing it out in case this is helpful to others who are reading.

Inspired by Daniel Munoz’s post above, I’d like to add that I think the considerations here interact with those in Kevin Zollman’s recent post concerning non-academic employment for philosophy PhDs.

I don’t know if doing a doctorate in philosophy is more economically risky than doing a doctorate in other humanities fields. I’m quite sure it’s more economically risky than doing a doctorate in many/most STEM fields, and probably many social science fields as well, because the pipelines to non-academic employment are much better developed in those fields.

If you’re used to not being able to take economic security for granted, then embarking on a 5-7 year course of study with no sure prospects of employment at the end can seem like madness.

So I’m inclined to think that a substantial part of our efforts to improve the situation with respect to diversity and inclusion in philosophy should involve doing whatever we can to improve the non-academic employment prospects for philosophy PhD students along the lines discussed in Kevin’s post, and then once we’ve done that, making sure that undergraduates who might be interested in graduate school know about it. While that’s not intended to discount the importance of cultural changes, I tend to think that without material changes in employment prospects, it will be hard to substantially increase the number of first generation college students who go on to do graduate study in philosophy.

I agree with the last part of this comment, but I am not sure that philosophy is more economically risky, overall. I recall this study from the other APA, for example (https://www.apa.org/monitor/2017/06/datapoint): “In 2013, approximately 35,300 psychology doctorate recipients were employed full time at four-year educational institutions..For psychology doctorates with less than 10 years since doctorate, 44 percent were tenured (12 percent) or tenure track (32 percent)”. So, for those in academia with a PhD in psychology, 44% are in a permanent academic position. The APDA project has 43% of those with degrees 2012 and later who are in academic employment in a permanent position. (If I go back to 2009, it is 55%, but the sample from years prior to 2012 is biased in favor of those in permanent positions.)

I may be misunderstanding, but this seems to just speak to the comparative riskiness of philosophy vs psychology when it comes to employment *within* academia. My point was that while permanent academic employment is hard to come by in pretty much all fields, some do better than others at providing paths to non-academic employment. What I’d like to know would be what the employment situation is like for psychology PhDs outside of academia, and how that compares to philosophy.

That said, the willingness of psychology PhDs to remain in non-permanent academic positions at rates similar to philosophy PhDs might suggest that their employment prospects outside of academia are comparable to those of philosophers.

Right, I don’t know of a systematic comparison of all types of jobs across fields like this. Do share if you know of one. But I think philosophers often assume that the academic job market is better for other fields, and I am not at all sure about that. As philosophers are especially focused on academic jobs (92%, I think, prefer academic jobs), this seems important. Yet, ever since hearing a podcast about the nonacademic job market for economists I have been motivated to explore what would work for philosophy (https://www.npr.org/sections/money/2017/05/05/527087730/episdoe-769-speed-dating-for-economists). I am actually working with Kevin and Jonathan Weisberg on a paper about nonacademic placement now. It is an excellent point, and one I agree with.

I’ll check out the podcast, and great to hear about the paper; thanks for doing this work!

“It is hard for me to imagine a shared characteristic between these many different groups that is more significant than the fact that they have been historically marginalized.”

This seems odd– why think one factor ought to explain them all? Furthermore, it seems misleading to talk about underrepresentation by social group and then not control for other factors, especially if we’re going to start talking about the causal contribution of things like stereotypes or makeup of the department. E.g. I’m willing to bet a lot of money if you look at the representation of African Americans after controlling for parental income and number of college degrees, the gap will be a *lot* smaller, and it will be clearer that the reason for this discrepancy between philosophy’s makeup and the general population probably isn’t because of QandA etiquette. That’s not to say racism etc doesn’t happen, or it isn’t important to ask how historical oppression contributed to class differences, but we risk doing a lot of yelling and floundering and not much helping if we just go from observing a discrepancy, noting that there are some studies suggesting stereotypes etc make some difference, and then conclude that stereotypes and oppressive practices within our discipline are what’s doing the work and so that’s where we should focus with no demonstration of causality or any consideration of effect size.

Also, more broadly about this topic, it strikes me as risky to try and analyse how to close certain gaps by asking graduate students what would help, and then making concrete recommendations with the implication being that anyone who doesn’t follow them is thereby contributing to under-representation. There is a glut of graduate students, a very large proportion will not get jobs in academia regardless of our department’s climate, and we have no reason to think any have some special insight into whether they’ll be one of the ones who get a permanent position ahead. It’s not like all the white students who don’t get jobs just weren’t competitive enough, and all the minorities who don’t get jobs self-selected out due to department culture. Again, not to say there aren’t independent reasons for making a warmer climate, but then we should just talk about those reasons directly instead of citing statistics showing gaps as proof that a warmer climate will necessarily improve representation.

Relevant: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/03/19/upshot/race-class-white-and-black-men.html

“I’m willing to bet a lot of money if you look at the representation of African Americans after controlling for parental income and number of college degrees, the gap will be a *lot* smaller, and it will be clearer that the reason for this discrepancy between philosophy’s makeup and the general population probably isn’t because of QandA etiquette. ”

Whilst this seems like a plausible hypothesis for explaining the gap between the proportion of the US general population who are African American and the proportion of philosophy doctoral students who are African American, I’m not sure this tells strongly against the authors’ arguments. Firstly, this hypothesis seems less likely to explain differences between doctoral students in philosophy and doctoral students in other disciplines. Secondly, analogous explanations are very unlikely to apply to other demographics picked out by the authors, such as gender. Thirdly, I take it that the authors would view an explanation in terms of socioeconomic disadvantage as another, different kind of loss.

“…we risk doing a lot of yelling and floundering and not much helping if we just go from observing a discrepancy, noting that there are some studies suggesting stereotypes etc make some difference, and then conclude that stereotypes and oppressive practices within our discipline are what’s doing the work and so that’s where we should focus with no demonstration of causality or any consideration of effect size.”

This is not a reasonable or charitable reading of the argument of this blog post. For a start, far from ‘concluding that stereotypes and oppressive practices are doing the work’, the author explicitly writes that they ‘don’t know’ what the cause is whilst outlining some reasonable hypotheses that they say require further experimental investigation and requesting feedback on methods. For another, this report sounds like it’s based on extensive feedback and participation from members of these underrepresented groups. Whilst testimonial evidence certainly doesn’t count as *conclusive* empirical evidence about which methods might have a positive or negative effect on diversity and with what effect size, it *is* still contributing to a body of evidence. I suspect that the author would welcome further empirical evidence on this question. Indeed, implementing some of the suggestions might contribute to this evidence.

Hi Joanna, I agree pointing to parental income won’t explain differences between philosophy and other disciplines, or gender gaps. I guess my point was more we need to do a better job of separating ‘in house’ factors contributing to gaps (e.g. stereotypes, climate, conference etiquette) from those which have had the bulk of their effect before students even take their first undergraduate class and which we’re pretty unlikely to be able to fix (e.g. effects of socioeconomic disadvantage, culture), and how we need to talk much more about effect sizes, instead of just saying ‘some contribution’. It seems relevant, for example, that children of doctors are several times more likely to become doctors than their peers, even after controlling for class. Plausibly, exposure from a young age helps children make it easier to think of themselves in various kinds of careers, so schemas have a big role, and schemas have been widely pointed to in the literature on philosophy’s gaps. But for some reason, all the in-house talk about schemas focuses on things like syllabi and representation on panels, with no one bothering to show that these things have measurable effects on student’s schemas in the kind of way that contributes to gaps, or that changing these things will reduce gaps. Yet calls to diversify syllabi etc for the purposes of explicitly improving representation are very very common.

I agree the blog post doesn’t explicitly make the inferences I pointed to, but I take them to be heavily implied by how CDJ explicitly chose to emphasise in bold things like ‘bystander and climate training’ and ‘diversity coordinators’, how taboo it is to suggest in these discussions that maybe the overwhelming majority of these gaps is caused by factors which have their effects before students enrol in university, and how much of the research paper chose to investigate things like climate and graduate experience vs how little of it looks at e.g. the effects of socioeconomic disadvantage and parental education. This sleight of hand from ‘factor x may contribute somewhat’ to ‘X is making a significant impact, we need to make changes to x and if you don’t you’re contributing to the problem’ is regularly made in the literature on philosophy’s gender gaps and discussions on places like DailyNous, and it isn’t helpful.

Is the substitution of first generation at university for socioeconomic class because the former is available and has some correlation with the latter? Is information about family wealth not available for these populations? I assume yes, but am not sure.

From what I have read, two standard tests of SES are income bracket and education level of parents. We did both, but focused on first generation status: “The proportion of those in different socioeconomic classes is often determined by income. The Pew Research Center, for example, reports that in 2015 29.0% of those in the United States were in the lower class, 49.9% in the middle class, and 21.1% in the upper class [12]. Our survey instead used self-report, with 23.3% in the lower class, 43.3% in the middle class, and 33.4% in the upper class. A direct comparison of these values reveals an upward shift in our participants, relative to the U.S. population. A more straightforward comparison on the basis of socioeconomic status, perhaps, is “first generation” status. This status applies to all those for whom neither parent earned a baccalaureate degree. In 2017, 58.9% of children under the age of 18 have no parent with a baccalaureate degree [13]. 30.7% of all doctoral students are first generation (CI: 30.3% to 31.1%) [14]. In comparison, 23.4% of our survey participants are first generation (CI: 20.6% to 26.2%).”

Thank you.

Hi Dr. Jennings,

Thanks for this, and for your thoughts. Some of my colleagues in I/O psychology helped me to do the 2017 equity survey in Canada. The concluding section of our report synthesizes some of the recommendations from participants and might be of some use. That said, much of the content of what was said overlaps with some of your thoughts in the OP. Here’s a link: https://silkstart.s3.amazonaws.com/9380cb46-71a1-428f-953d-aa683db6755a.pdf

Thank you!

It would be nice to have these data and proposed measures situated within prior research. For example, my lay impression of the research on the efficacy of diversifying syllabi and diversity training workshops is mixed at best, and that the latter has the potential to be harmful, helpful, or neither, for varying lengths of time, depending on various factors that we’re slowly coming to understand.

With regard to the data, it seems to me that any discussion of explanations must include the fact that the group differences begin before college. This reminds us of the commonsense fact that these groups’ interests and preferences are shaped by their environment from early childhood in such a way that they choose careers and academic disciplines other than philosophy. This has to be part of the explanation of the data presented here. Moreover, it would be surprising if such deeply ingrained preferences and interests had no effect on people in grad school. This is consistent with at least some of the research on training workshops, which finds that these workshops are ineffective without broader social changes.

So if future research on this is to identify the biggest contributors to the group differences, my money is on the identification of the specific interests that lead different groups to choose differently; I’m thinking something along the lines of this:

https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/features/cou-cou0000164.pdf

Thanks for doing all the work to collect and organize this data, Dr. Jennings. Things like this and the APDA are just really great to have available to refer to.

I wanted to comment about something you say in your post. You write: “As we know, the obsession with “genius” is correlated with a lower proportion of women and Black/African Americans across disciplines, and philosophy is especially obsessed with genius. Yet, philosophy also has a lower proportion of Asians than other doctoral programs, which cannot be explained this way. Further, I don’t know of a stereotype or bias regarding innate intelligence when it comes to socioeconomic status.”

You’re making a point here about how we shouldn’t expect the bias toward “genius” to explain all the different groups that are underrepresented in philosophy, which conclusion I agree with. But I thought it was strange to claim that you don’t know of a stereotype regarding the innate intelligence of low-SES people. The stereotype is that they’re stupid. Maybe in the abstract a typical philosopher wouldn’t doubt that some poor person could be a genius or whatever, but surely someone displaying the signs of low-SES will get viewed as less intelligent than their peers. If a student talks in a Southern dialect and drives a rusty old F-150 to campus, most people will assume they’re not intelligent.

Maybe that means something for our explanations of who’s underrepresented and why, and maybe it doesn’t but I just wanted to make that point. Thanks again for compiling this survey.

Thank you. I am aware of the bias against the Southern dialect, but did not connect that to SES. I take your point.

As someone from a lower SES background, this also surprised me. There are all sorts of markers of class that are held against people in the academic world, so this also surprised me. (Further, a lot of the ‘genius’ stereotype has to do with being ‘articulate’/about the way you present your ideas etc., which itself is a product of things like where you went to school in K-12th grade, how your parents speak, what kind of neighborhood you grew up in and who your friends were, and so on.)

“A new possibility I have considered, but haven’t tested, is that the sheer variety of topics and methods in philosophy leads philosophers to seek demographic unity in order to maintain a sense of cohesion.”

This strikes me as a very interesting hypothesis that, if true, would seem to cut against at least some proposals like the following:

“Changes to core philosophical curriculum to include more areas outside of LEMM and Ethics”

Many people seem to have a thought that intellectually diversifying what counts as a single discipline will be related to demographically diversifying it. But I think that is very far from obvious. It could well be that dividing departments called “philosophy” into several separate disciplines could create smaller departments that provide better homes for people with diverse backgrounds of various sorts. (Or it could be awful on this front – hard to say without more data.)

I would like to second Daniel Munoz’s point above – ‘More generally, we shouldn’t just ask what diverse students can do for philosophy; we should ask what we can do for them’. Whilst I think it is interesting to wonder why certain groups are underrepresented, and if *philosophers/philosophy* are/is somehow doing something to sustain such imbalances, I think it is important to understand that actively trying to correct these imbalances is a different matter entirely. Maybe it is a mistake to think of it this way, but I am inclined to think that taking people into the discipline is a responsibility – or perhaps better that we have responsibilities to those that we entice to be here. And a lot of the talk I hear around me would appear to second this kind of understanding as well. But in my experience after a decade and a half involved in the discipline, these responsibilities are neither well understood nor easily actualizable. I could not count the number of women I know who have ended up stuck in towns or cities they would never have otherwise dreamed of living in, either single or in perennial long-distance relationships, childless, lonely, and generally extremely unhappy. I could not count the number of people I have spoken to who have burned down their lives to wind up in unfamiliar communities with colleagues who talk and talk about diversity and inclusion, and somehow think hiring a young black female and then throwing a cupcake and pizza party when she arrives is what counts as being progressive and embracing. In my experience, the enthusiasm for progress-at-any-cost very often has extremely damaging consequences for the people’s lives who are caught in its cross-fire. And I absolutely do not mean to convey the idea that this is because philosophers are somehow, en masse, terrible people. The longer I live in University land, the more I understand how many broader complexities there are in diversifying the academic community. Spousal accommodations, for example, *disproportionately* affect women as women are *far more likely* to have academic partners than men are. And more often than not, a department will be at the mercy of university policy and/or budgetary constraints when it comes to being able to make such accommodations. Moving people into radically different communities than the ones they are used to – and this can happen whether you are an African American moving to an extremely white college town, or an extremely white person from Iceland moving to rural Kansas – is, in my experience, just difficult for human beings. For some strange reason, we understand very well that being an immigrant or a transplanted person is hard when you’re a shopkeeper from Syria, but we seem to understand it much less well when the immigrant or transplanted person is an academic philosopher.

I do not mean to suggest that philosophy should not try and diversify. Not at all. I just mean to convey the sentiment that doing it well is actually complicated and involves many broader human and societal factors that are beyond our control as a discipline (but that I think we ought to endeavor to be a bit more aware of). Sometimes I worry that in a great effort to reassure ourselves that we are not somehow terrible people, we rush headlong into the promotion of diversity and inclusion without giving enough thought to what the consequences of that might be for the human beings who are caught up in it. I hope I have not conveyed anything negative about Dr. Jennings’ study – that was absolutely not my intention either.

I’m worried that the suggestions for fixing philosophy’s diversity problem are off target here. The focus seems to be on what *graduate programs* can do to increase diversity, but that lack of diversity seems to be downstream of a lack of diversity among undergraduate philosophy majors. In the Thompson paper linked to above, the author says that women make up 30% of philosophy majors, and in the infographic here the percentage of female doctoral students is listed at 33.8%. I would suspect (though I have no evidence) that you’d find similar numbers among other underrepresented groups as well. So, if philosophy ph.d program demographics roughly approximate the demographics of philosophy undergraduate majors, shouldn’t our focus be on recruiting a more diverse set of undergrads rather than making changes to ph.d. programs?

Changes can certainly be made to graduate programs that would make the climate of professional philosophy more inclusive and hospitable, but if our concern is to increase the number of philosophers from underrepresented groups, then I’m not sure we’re looking in the right place.

As far as I know, there is a reduction in the percentage of women from undergraduate to graduate education: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1527-2001.2012.01306.x . Yet, it may be that the proportion of women in graduate school is starting to go up, after many years of stagnation: http://placementdata.com:8182/feminist-philosophers-blog-impact-on-placement/

Hi Carolyn, the study you linked concludes that the only statistically significant drop is found “between taking an introductory class in philosophy and declaring a major in the field. Furthermore, there are no other statistically significant drops in the proportion of women as we continue through the academic hierarchy.”

Nate’s point stands, I think. Clearly most of our energy has to be directed at the intro/undergrad level, that’s far and away where we are losing the greatest number of people. The under-representation issue shouldn’t be misrepresented as a problem that can be fixed in graduate school! (That’s not to say that some of the suggestions above aren’t potentially helpful).

That’s true—thanks for pointing that out. There may nonetheless be a drop. I would have to do a more systematic review to be sure, but Eric Schwitzgebel has noted that the percentage of women majors “never strays from the band between 29.9% and 33.7%” whereas he and I found that women PhDs had been long stalled at 27-28% (https://faculty.ucr.edu/~eschwitz/SchwitzPapers/WomenInPhil-160315b.pdf). The recent uptick in women in doctoral programs is still only just over 30% (http://placementdata.com:8182/feminist-philosophers-blog-impact-on-placement/). So, yes, there may be other places we could put our energy, but this may nonetheless be a real problem even at this level. And, of course, this is only to talk about the percentage of women, leaving out the experience of being less comfortable in philosophy, finding it less welcoming, etc. etc. that women and many other underrepresented groups also have in their doctoral programs.

I don’t understand why this ignores ethnicities other than those listed. For instance, many leading graduate programs in philosophy have South Asian and Middle Eastern students. The latter group especially tend to be counted under ‘White’ for some reason that I cannot comprehend.

I have several questions:

1. How can the graduate division become more diverse if the candidates pool has not?

2. Why are we drawing women (and members of other underrepresented group) away from pursuing research in STEM fields, which most laypeople hold in higher regards (because of the high impact of technology and health care) than the humanity fields?

3. Don’t you think that most women, African Americans, Hispanics, and Asian Americans are trying to pursue a study path with the most job prospect with high wage in order to improve the status of their respective groups within society? I am an East Asian myself, and my parents were disappointed when I chose to pursue philosophy.

4. Diversity? Diversity of what? Does the field not have an ‘ideology’ problem too? Also, what about cultures (where are non-American students)? I can ask the same thing about other characteristics that a person can have. Yes, I am questioning the belief held by most Americans who call themselves liberal or progressive just as I question conservatives’ belief that the U.S. is a Christian nation. Why should I, as an inquirer as opposed to a person of faith, exempt any beliefs, claims, or ideologies from being questioned and analyzed? Philosophers have been questioning about which actions are moral and which are immoral (moral theory), which situations are just and which are unjust (theory of justice), and even whether or not one can be certain about the existence of the external world (epistemology). In other words, philosophers have been asking whether a lot of our common senses are justified or not, and ethics is not a settled field.

5. Do you think that it is necessary to reassure incoming grad students that their pre-existing beliefs and ideologies would never be questioned by anyone within the field and that those beliefs would only be confirmed so that they would not leave the field later? There was recently a transgender philosophy student who left the field because of the presence of TERFs (‘gender-critical feminism’) and what she (I think this is her identification) perceives as transphobia within philosophy. Perhaps Christian philosophy students can complain about what they perceive to be christophobia in philosophy too by citing how the existence of God is questioned by most within the field.