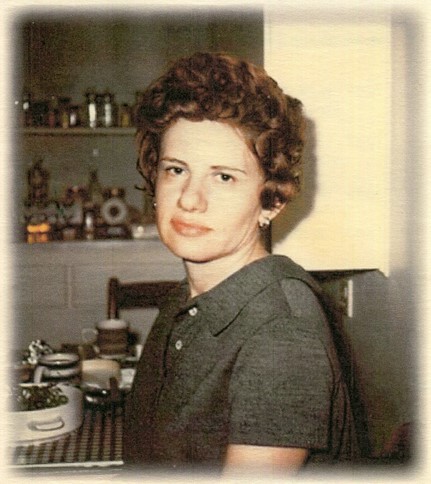

Gertrude Ezorsky (1926-2019)

Gertrude Ezorsky, professor emerita of philosophy at Brooklyn College and the City University of New York (CUNY) Graduate Center, died this past April. The following is an obituary written by Nanette Funk and Andrew Wengraf. It describes Professor Ezorsky’s notable career and character, as well as the remarkable hurdles she had to overcome in her career.

Obituary for Gertrude Ezorsky

by Nanette Funk and Andrew Wengraf

Gertrude Ezorsky, professor emerita, in the philosophy departments of Brooklyn College, and the CUNY Graduate Center, died at home peacefully on April 19 age 92. She combined excellence in analytic philosophy with a courageous commitment to political and social change in a career of rigorously argued, scrupulously researched work, always lucidly presented in her terse, plain style. Drawn to lively and controversial issues with live applications. Gertrude took clear stands, some notably controversial, and she refused to bury her opinions in disclaimers. She secured this reputation with steady early work of the highest quality. Her earliest papers appeared in the elite journals, and her talent gained her the respect of men of top rank in the profession, including Hare, Hampshire, Isaiah Berlin, William Frankena, Chisholm, Maclntyre, and Morgenbesser, as well as her former professor Sidney Hook—this at a time when all but very few women were hardly acknowledged in philosophy.

Gertrude attended Brooklyn College, returning to teach there fresh out of graduate school. Before going into philosophy Gertrude had done factory and office work and taught elementary school.

She started her philosophical career working on traditional issues in epistemology and the nature of truth. She then published in ethics and metaethics, especially on utilitarianism, and she argued for an augmented consequentialism. Her lengthy assessment of Marcus Singer on generalization in ethics and her discussions of the work of Lyons and Rawls on the relation of act and rule utilitarianism earned her much attention. She then moved on to issues of justice and applied ethics. Gertrude challenged many all too easy empirical claims of equal opportunity and freedom, taking stands on discrimination against women, on justice in punishment, on discrimination in hiring of blacks and justice and on freedom for workers, freedom in the workplace being the subject of her last book.

Looking back, the hallmark of her argumentation is to put social truths in context, showing the empirical premises and contextual nature of the assumptions of theorists who lift their social principles away from both particular and generalized contexts. Gertrude thus exposed certain stereotypes and errors of reference in theories infatuated by negative liberty. Her concise criticism of Judith Thomson on the rights of employers in Philosophy & Public Affairs is a good case in point. Her lead article “Fight over University Women” in the New York Review of Books in 1974 was a path-breaking knockdown attack on discrimination against women in the university that indicted the academic establishments at Harvard, Columbia, Berkeley, and Chicago and her own employers at City University of New York. Her article “Hiring Women Faculty” in Philosophy and Public Affairs continued that analytical argument. Her case was reprinted in the Congressional Record and in the Hearings of the House of Representative Subcommittee on Education and Labor. This research is a crucial document of that time, a scathing documentation of discriminatory attitudes and practices toward women in the university, and a fine piece of applied ethics. Gertrude single-handedly organized a full-page petition in the Times with 3000 signatures on behalf of affirmative action in hiring university women. This influenced then-President Ford to permit some affirmative action in hiring women in the university. Gertrude was also an active consultant in an important class action suit that established gender discrimination in CUNY. Many women in academia, however eminent or entitled to their current status, would not have work beyond the former level largely reserved for tokens of particular ability or niche recognition without the efforts in which Gertrude was a bona fide leader.

Racism and Justice, her defense of affirmative justice, written at the height of criticism of affirmative-action policies, sold over 14000 copies. One can attribute this to its strong pedagogical value, because even when students were inclined to disagree with it, they were denied the false stereotypes of an already just and meritocratic social or legal context from which opposition to such policies often started. She offered clear and cogent arguments, not strawman versions, on behalf of affirmative justice, thus sharpening the issues. Gertrude was quick to see that her proposals did not become uniform policy. Her arguments were blunted and deflected by determined opposition, her proposed numerical criteria were turned into a terminally vague appeal for diversity, and her demand for compensation for any truly displaced white males was rejected by the white male power structure itself, which refused to pay the cost of compensation.

Right or wrong, Gertrude was a model of intellectual integrity, a fearless woman loyal to those wrongly treated, willing to challenge those in high places. The writers she challenged were not personal rivals, except insofar as they were intellectually dishonest; the real competition for Gertrude was between ideas. Gertrude would raise fundamental criticisms with vivid real-life examples, not to score points, but because her significant philosophical abilities are always informed by compassion, moral sensitivity and a pragmatic sense. Her opponents included Hook, Rawls, Lyons, and Thompson aforementioned, Levin, Nozick, and Alvin Goldman. In her early criticism of Hannah Arendt’s use of Eichmann as a paradigm of the banality of evil, Gertrude argued that Arendt disregarded context, miscast the murderous Eichmann, and adopted half-truths as empirical premises. The charge was essentially about empirical assumptions, and remains controversial almost sixty years later.

She was a cradle egalitarian and activist who did not bemoan injustice, elitism, academic dishonesty, evident unfairness, or brute exercise of power, but stood up up against them. She spent much of her energy fighting for those much more vulnerable than herself with action guided by the same acute, precise analysis she brought to her publications. She saved the jobs of several men and women who were victims of wrongful treatment, to which I can personally attest.

I knew Gertrude since we became colleagues at Brooklyn College. A year out of graduate school at Cornell, I returned to the city, having quit my first teaching position. Someone suggested I call Gertrude, who helped find people jobs. Not only did she find me an opportunity at Brooklyn College, but she also took me seriously as a professional, inviting me to meetings of analytic philosophers and other New York intellectuals. The impact on me was tremendous. I sat in the subway on the way to a meeting, with a new sense of myself, thinking I must be a real intellectual if Gertrude invited me to such meetings. When I was threatened with firing early in my career, Gertrude did labor- intensive investigations of probably over 100 hours into the entire history of the Brooklyn College Philosophy Department and its present practices, showing that she was the only woman to have ever gotten tenure or become associate professor. She constructed the winning legal argument presented by our union’s grievance counselor in my case. It was one of the first decisions at the college based on evidence of gender discrimination. What was happening to me recalled to Gertrude her own very recent rebuffs in the department, by some of the same people and same prejudices pervasive throughout higher education, as Gertrude knew only too well. I was stunned to discover that in spite of all the recognition she had received, Gertrude encountered discriminatory treatment. Hired only as an instructor despite her PhD, she was later discouraged by her chair from applying for promotion to associate professor although she had by then published 14 articles in leading journals. She was passed over in favor of a man with two articles in philosophy, one a joint publication. She was also told that she would be supported for promotion only if she undertook secretarial duties, a confirmed affront which defies belief today. When Gertrude was rightly placed on the CUNY doctoral faculty at the Grad Center in the late 1960s, she was never told, nor given courses to teach, until the university was monitored for discrimination years later. Later in the 1980s at the Graduate Center she dealt with even more hostilities and injustices, in part because of her position on affirmative action.

Gertrude’s efforts on my behalf were dramatic efforts in my professional life, but also significant reflections of her principled concern for respect for women in philosophy. Only recently others have told me how influential Gertrude was in helping them establish their career. Without her strong efforts, several other women in the department would not have gotten tenure. Few women in the profession of her generation were so outstanding professionally and yet gave so much of their time and effort to help others while also providing such notable service to the profession in general, publishing successfully all the while. These efforts were certain to garner Gertrude enemies, and they did. For anyone in academia to dare to act in such a way is remarkable—for a woman of that day it was singular. No matter how many enemies Gertrude made in these struggles, if there was to be a struggle, Gertrude came to fight. Her fights were principled appeals to justice against an essentially male establishment, but her principles were always stated with such clarity that they won the support of fair-minded men. Whenever one hears Gertrude described as a troublemaker, and who has not, one should think of the troubles she made on behalf of the entire profession and the cause of justice, and of what this troublemaking helped us to gain. To call her a troublemaker is to tacitly bestow on her a particular honor. We can leave it at that.

Gertrude is survived by her husband of many years, Eli Cohen.

(This obituary first appeared at New Politics.)

Ezorsky’s book, Freedom in the Workplace, is excellent for classroom use.

This book treats a topic of interest to nearly every student. It applies conceptual analysis to reveal distinct concepts of “freedom,” and poses moral problems using real-life examples. All in Ezorsky’s straight-to-the-point style.

Freedom in the Workplace is radical, and businesslike about it.

I recommend buying the book directly from the publisher, Cornell UP:

http://www.cornellpress.cornell.edu/book/?GCOI=80140100446020

Sigh.

Gertrude Ezorsky was a fine person and a fine philosopher, often persecuted by jealous and spiteful colleagues, but rose above it and commanded the respect of everyone whose respect was worthy of commandment. Through the example she set, she did more for women in philosophy than anyone else I can think of, and I am proud to have been some help to her, albeit all-too-modest. She had a good run, making it to 92, and death at such an age is rarely tragic. But I nevertheless hear of her death with great sadness. Aside from everything else, she was a great friend to me, although I haven’t been with her in person for what I guess is now 40 years. Goodbye, Gertrude. Thanks for being with us and for being you.

Mikael M Karlsson