Which X-Phi Studies Replicate?

“Different types of experimental philosophy studies showed radically different rates of replicability,” according to a new analysis by the XPhi Replicability Project.

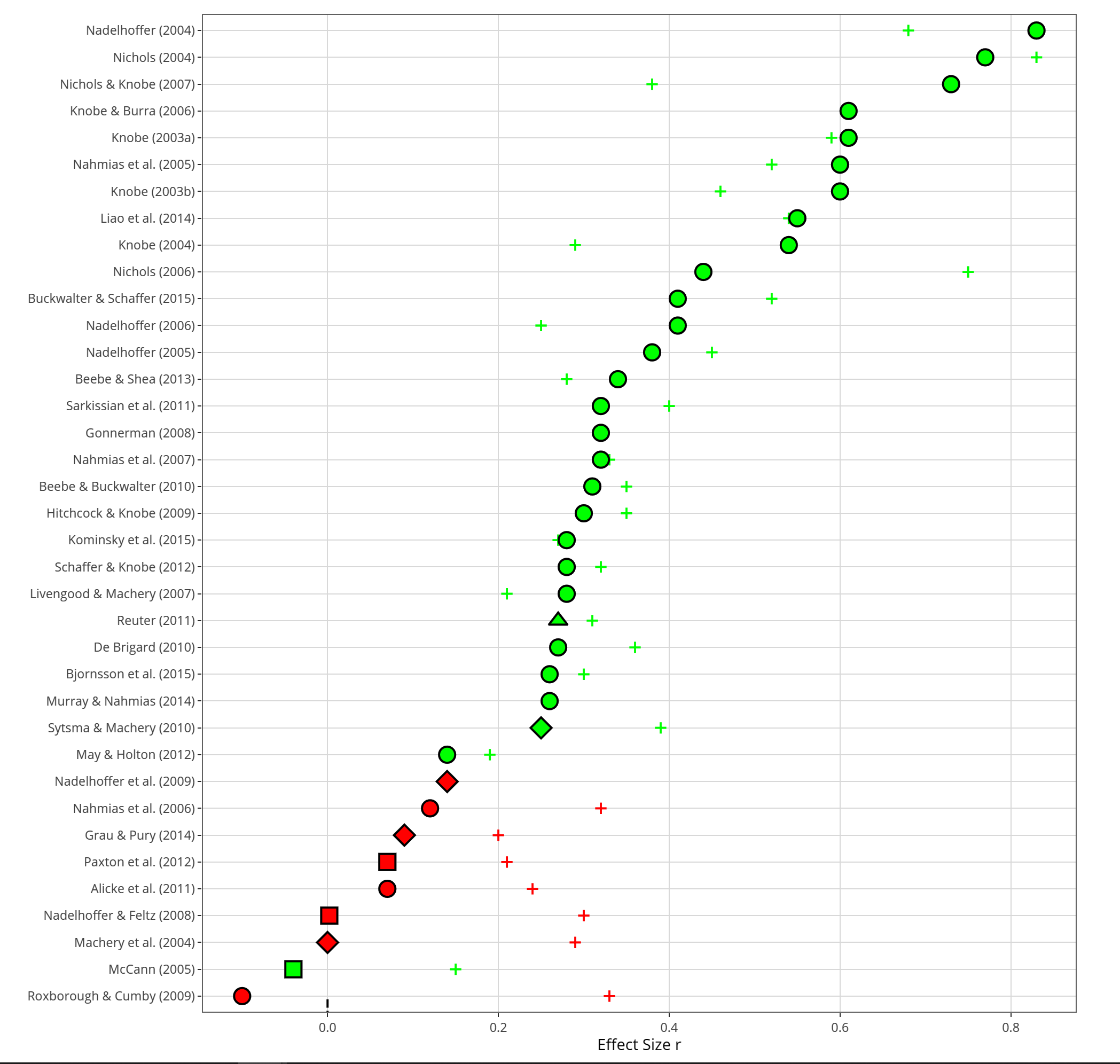

The investigators sorted experimental philosophy studies into three types:

- Content-Based Studies: “participants receive hypothetical cases that differ in some systematic way.” (Represented by circles on the graph below.)

- Individual difference studies: “all participants receive the same case, but the researchers observe a difference between the way different types of participants respond to it.” (Represented by triangles on the graph below.)

- Context-based studies: “all participants receive the same question, but the experiment manipulates some other factor in the situation that might impact people’s answers.” (Represented by squares on the graph below.)

The investigators write:

As you can easily see [on the following graph], the majority of experimental philosophy studies are content-based, and these studies show very high rates of replicability. A minority are either individual difference studies or context-based studies, and studies of these other types often fail to replicate.

Further details, including links to the full replication information for each of the listed papers, is here.

(via Jonathan Phillips)

This is a misleading analysis in various respects:

1. Very few studies looking at demographic effects were included in the replication. As a result, it is unwise to generalize from these few studies.

2. The main comparison is confounded by the effect size and thus by the power of the replication. Studies looking at demographic effects are focusing on smaller effect sizes. As a result, the replications have lower power and it is not surprising that they report negative results.

Indeed, if you look at the results, you see that for many of the studies looking at demographic effects, the mean is in the same direction as the original one (e.g., Grau & Pury), although smaller. No effect was obtained possibly because of a lower power. A metaanalytic approach would have resulted in a different analysis.

3. Some of the negative results reported here (e.g., for Machery et al. 2004) are outliers in the literature – the basic effect having been replicated independently by various groups.

4. One of the failed replications (Nadelhoffer et al. 2009) in fact establishes a demographic effect: It fails to replicate a paper (Nadelhoffer et al. 2009) that claims that there is no demographic effect and in effect successfully replicates a previous paper by Feltz and Cokely.

So, Phillips draws the wrong conclusion: it is not that studies that look at demographic effects are less likely to replicate; it is rather that they look at smaller effects that require larger studies and a metanalytic analysis to identify reliably.

Hi Edouard,

Thanks for these very thoughtful and informative comments. I was actually the one who mainly wrote that webpage, so I’m happy to be the one who responds here. (One quick further note: Although I was the one who wrote the actual sentences in that webpage, what I wrote was an almost verbatim summary of content that was written by other people and appears in the published version of the replication paper. So the interesting objections you raise here might actually be best understood as objections to a passage in the paper itself.)

As the paper notes, the basic pattern of the results was that content-based studies tended to replicate successfully, while demographic effects and situational effects tended not to replicate successfully. If I understand correctly, you are not objecting to this summary of the findings themselves. Rather, you are objecting to a certain conclusion that one might potentially draw based on those findings. Specifically, it seems like you are saying that it would be wrong to conclude on the basis of these findings that people’s intuitions show little impact of demographic or situational factors. This is definitely an interesting suggestion, amply worthy of further discussion.

Many of the specific points you make in your comment are well-taken. It is indeed true, for example, that your finding about cross-cultural differences in semantic intuitions has been replicated by a number of other studies. (I will link to some of the studies in a subsequent comment, but I won’t include them here just to make sure this comment is not held up in moderation.) It is also true that the replication of the Nadelhoffer et al. paper found a significant effect of an individual difference factor. This factor was not a demographic factor in the usual sense but rather a personality variable, but all the same, you are completely right to say that this personality variable seems to be impacting people’s intuitions.

You hypothesize that the difference between the replicability of these different effects might be due to a difference in the effect sizes observed in the original studies. That is, it might be that demographic effects and effects of situational variables are just small effects, and therefore less likely to successfully replicate. I don’t see this as disagreeing with the claim I was making, but rather as providing a possible explanation for the pattern I was describing. The pattern is that demographic effects and situational effects less often replicate successfully. Your proposed explanation is that these are simply smaller effects.

Finally, you note that even if demographic effects and situational effects tended not to replicate within this specific sample of 40 studies, it would be a mistake to conclude that studies finding these types of effects tend more generally not to replicate. Although you are right to say that one should not draw any strong conclusions from this one specific sample, I do think that the pattern observed in this specific sample is fairly representative. It is true that your own work on demographic effects has proven highly replicable, but you are clearly an outlier in this respect. Although your own work has consistently replicated successfully, many, many other studies purporting to find demographic effects have failed to replicate. I am reluctant to include links to these replication failures here (just because I wouldn’t want readers to think poorly of the researchers behind the original studies). However, in a separate comment, I’ll include a link to a paper from your own research in which you argue that the purported cross-cultural difference in Gettier intuitions does not actually exist.

Similarly, there have been a large number of studies suggesting, in one way or another, that previous work arguing for an effect of small situational manipulations actually fail to replicate. The patterns observed in the experimental philosophy replication project simply conform to this more general pattern in the existing replication literature.

Finally: Philosophical debates on blogs can sometimes get a little bit weird, so I just wanted to say explicitly that even if we don’t end up converging on these issues, I very much welcome your criticism. Your published work has criticized my views on a number of different topics (intentional action, consciousness, etc.), and I’ve always learned a lot from your objections. Now we are discussing matters on a blog rather than in published journal articles, but I hope that our discussion will be similarly fruitful.

As promised in my previous comment, here is a follow-up with a few links.

A couple of papers that successfully replicate Edouard’s cross-cultural finding for intuitions about reference:

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10670-014-9653-6

https://academic.oup.com/analysis/article/69/4/689/153361

Edouard’s own paper arguing that Gettier intuitions are actually surprisingly robust across cultures:

http://fitelson.org/prosem/gac.pdf

(For what it’s worth, I strongly recommend reading this paper.)

Hi Edouard,

As Josh mentioned, I can’t really take much credit the the nice webpage Josh made, but I did want to quickly follow up and ask for some clarification on a couple of the points you raised.

Re: 1. I don’t know of anyone on the replication project has argued for a generalization from this set of studies to anything like “all demographic effects on philosophically relevant intuitions”, so I was a little unsure where the objection to generalization was coming from. As you say, there aren’t many data points on demographic studies in this sample, and moreover, this kind of generalization would be an odd one to make even if there were more data — demographic variables are a varied and motley crew and what is true of some subset of them isn’t likely to generalize to the others. My memory is that everyone on the replication project was very aware of that and wrote the paper along those lines. On page 34, for example, we wrote “A low replication rate for demographic-based effects should not be taken as direct evidence for the nonexistence of variations between demographic groups. Indeed, out of 3 demographic-based effects that failed to replicate, one was a null effect, meaning that the failed replication found an effect where there was none in the original study”. Setting the generalization point to one side, though, the data obviously are informative about the demographic-based effects that were tested in the replication project and, by and large, those didn’t replicate, which is what I took Josh’s point to be.

Re 2. I was concerned about this point because I wasn’t familiar with the details of the power obtained when deciding on a sample size for the replication of the demographic effects. Fortunately, all that info is available for all of the studies on OSF (https://osf.io/pfng2/), so I went back and checked, and this just isn’t right. The replications of the demographic effects were extremely well-powered, in fact much much more well-powered than the original studies which reported these demographic effects. Just to give one example, the replication study of Grau & Pury obtained a power above .95! (For anyone unsure what this means, basically it’s just that this replication attempt had more than a 95% chance of detecting an effect of the reported size). You’re right, of course, that the originally reported demographic effects were smaller than many of the content-based effects, but that obviously doesn’t mean that there was a concerning confound with power: the replication studies of the demographic effects collected huge samples to ensure adequate power. (Btw, all credit for this should really go to Florian Cova, who was the actual force behind the replication project.)

I was intrigued by the meta-analytic suggestion, but I was a little unsure just from your short comment exactly what kind of approach you were thinking would be more appropriate. You obviously can’t do much with just the four studies in this sample, but if you were thinking something more general across all of the demographic studies we can find, I would be totally game to join forces check that out together if you wanted!

Jonathan

1. I am a co-author of the replication paper, and I have insisted during the writing of the paper that we don’t mischaracterize the results.

2. As you know well, you can’t compute power without assuming a given effect size. Computing the power of a replication assuming that the original effect size is the true effect size makes no sense at all since effect sizes tend to inflated (due to the cut off role of the significance level). Thus, the .95 power in the preregistration you discuss is a fiction. For a small effect size (d=.2), the power of a t-test for independent groups with 422 participants (the N suggested in the preregistration) is .5, not .95. That is, instead of wasting time and money, you’d better throw a coin if you are interested in the truth.

3. concerning the meta-analytic point, the idea is to take the original study and its replication and to aggregate these two results to get a better estimate of the true effect. This is what metaanalysts have been arguing for decades now (here is a classic reference: Schmidt, F. L. (1996). Statistical significance testing and cumulative knowledge in psychology: Implications for training of researchers. Psychological methods, 1(2), 115.)

Hi again Edouard,

1. Great, so we seem to be in agreement here!

2. Right, I think the assumption in replication project was that the only *practical* way forward was to estimate power based on the reported effect size but to make sure the studies were very well-powered (after all, what other specific number should they have used)? The original effect size in the Grau study was d= .4082, and so 422 gave them more than .95 power, but even if the effect size was half that size (d = .2), the power obtained by a sample of 422 is 0.8269, no? (In R, just run ‘ pwr.t.test(n=422,d=0.2,sig.level=.05,alternative=”two.sided” ‘, or you can calculate it online here: https://www.anzmtg.org/stats/PowerCalculator/PowerTtest ). That is, they had an 82.69% chance of detecting even a small effect of size d=.2. My sense is that studies powered at more than .8 are considered very well powered in general. Maybe we’re doing our power analyses differently, or using a different significance level?

Of course, it bears emphasizing again that none of this means that there isn’t a true effect there! It could be that the effect is actually just very very small, perhaps d=.02 (or < 5% of the originally reported effect) which would then mean that the replication study really was under-powered to detect that kind of effect. (At some point though, I would take that kind of enormous difference in true effect-size vs. original-effect size to itself constitute a non-replication.)

3. For the reasons you pointed out (inflated effect sizes for published results), the meta-analytic approach of just aggregating the original and replicated results is probably going to be a little misleading, but if I have a second later today, I'll try and dig into the details and see what that looks like! This kind of approach would obviously be better with effects with more attempts to uncover them, but let's see what the data say when we take this approach! I'll get back to you.

At any rate, these minor details aside, I think we're totally in agreement that these results should in no way be taken to indicate that there are not important and real demographic effects on philosophically relevant intuitions. Your work all on its own nicely shows that this is the case.

Quickly checking pwr.t.test n= is the number of observations per sample, not the total number of observations.

Good catch Edouard!! thanks!

So, updating the points from above in the light of this, the basic pattern we see is as follows. Given the sample size collected, the replication study of the Grau paper doesn’t actually have stellar power to detect an effect that’s about half of the original size. For anyone still reading, to get an intuition of what that effect actually looks like in the Grau study, an effect of d=~.2 translated into a difference of about 2.15 and a 2.5 on the 7-point scale with 1 labeled “not at all appropriate” and 7 labeled “extremely appropriate”. At the same time, the replication study did have sufficient power to detect an effect that’s about two-thirds of the original effect size (something more like the difference between 2.15 and 2.65 on the same 7-point scale). So, in short, if there is a real effect here, which is totally plausible, it is very likely to be on the smaller side, but need not be totally minuscule.

This might all seem a little in the weeds but the change above is really worth pointing out because it bears on Edouard’s worry and Josh’s points below in that it makes it more likely that there is a small but not totally minuscule effect that could have gone undetected in this replication. As Josh points out, the real work to be done at this point is in armchair philosophizing about what size of an effect we would need to observe for it to bear on the philosophical question at hand.

We’ll see if I can make any progress on the meta-analytic approach later today or tomorrow.

It seems worth noting that on top of this, the replication was conducted in Lithuanian and got a very notably different split in responses on the Godel probe. And as Villius’s team notes, this doesn’t match the results for other probes on reference in Lithuanian. So even if the power was adequate, I doubt much could be concluded about this particular study: the tool used to distinguish theoretically interesting groups in the original study isn’t reliable to begin with… and in the replication it was translated and gave radically different results. For purposes of determining how demographic effects replicate, this seems utterly uninformative.

re-power: weird. I use G*Power and get about .5. I gonna need to sort that out, perhaps by hand later.

Jonathan and Edouard are both making very helpful points. I imagine that some readers of this blog might have trouble understanding the more technical details of their comments, so I thought it might be a good idea just to summarize what they’re saying in more ordinary English.

The bigger an effect is, the fewer participants you need to detect it. So if there is a really big difference between two cultures, you could detect the difference in a study you ran on a relatively small number of people. By contrast, if there is a small difference between two cultures, you would need to run a study on a large number of people to detect it.

In the replication project, we proceeded by looking at the effect size from the original study and then figuring out how many people we would need to have a very high probability of detecting an effect of that size. So the smaller the effect was in the original study, the larger the number of participants would be in the replication study.

Jonathan points out that if the true effect size in these studies on demographic effects was anything like the effect size observed in the original study, the replication study would have successfully detected it. Edouard then says that the true effect size could actually be substantially smaller than the effect size observed in the original study, and indeed that there is specific reason to expect that the original studies are giving us inflated estimates of the effect sizes. Jonathan agrees that it is possible that there is a real effect but that it is smaller than what one would have estimated based on the original study. However, he says that, given the large number of people in samples used in the replication studies, the only way this could happen is if the true effect size was *extremely* small.

This debate may seem a bit technical, but in my view, it raises an important philosophical issue. Suppose that there really is a difference in intuitions between two demographic groups but that this difference is quite small – much smaller than we would have guessed based on the original studies. (If Jonathan is right, the Grau effect, if it exists at all, would have to be very, very small.) If that does happen, would this small demographic effect still have the kind of philosophical implications we might have considered when we thought there was a relatively substantial difference between demographic groups? Obviously, this is not the sort of question one can answer by running further studies. It is a philosophical question, to be answered through philosophical argument.

(Note that this issue does not arise for Edouard’s classic finding regarding cross-cultural differences in intuitions about reference. That one effect is clearly large enough to be philosophically important – but as we have seen, there is evidence that these other effects are not like it.)

Chiming in, I agree with Edouard here that we need to be very careful generalizing off of the results for these four studies on demographic effects. I think it is even a bit worse than appears at first sight: Unless I’m mistaken, the Grau & Pury (2014) result is using the Godel probe from Machery et al. (2004) to separate the groups (Descriptivists vs. Kripkeans). But the cross-cultural effect for that probe failed to replicate in the replication project (i.e., it is one of the four studies at issue here). And the numbers for that probe for Westerners have failed to replicate previously (see Sytsma & Livengood 2011; although the numbers in Sytsma, Livengood, Sato, and Oguchi 2015 were closer to the original). So, essentially, 2 out of 3 failed replications of demographic effects here rest on a probe that had failed to replicate previously… and that I think is known to have issues such that most subsequent work has used modified probes. (And the third is complicated by the issue Edouard notes, failing to replicate a failed replication.)

While Edouard is right that the basic effect for Machery et al. (2004) has been replicated independently by various groups, the probe used in the replication project studies hasn’t been so successful. The results that Josh links to (Machery, Olivola, and de Blanc 2009; Beebe and Undercoffer 2014) are using modified versions of that probe.

Hi Justin,

Wow, that is incredibly helpful. To be honest, I was completely confused about how the Machery et al. 2004 study could have failed to replicate, and this new information makes everything seem a lot more comprehensible.

Let’s put the larger issues to the side for a moment and just try to clear about what is going on with this one specific effect. Is your thought that that there might be some problems with the precise materials used in the Machery et al. 2004 study but that the basic claim made in that paper is still true and can be vindicated with the slightly modified materials used in Machery et al. 2009 and other similar papers? If so, can you say a little bit more about the differences between the materials in these different studies?

Hey Josh,

Glad it is helpful! Yes, that is exactly what I think is going on. Focusing just on the Godel case, the question in Machery et al. 2004 asked:

When John uses the name “Gödel”, is he talking about:

(A) the person who really discovered the incompleteness of arithmetic? or

(B) the person who got hold of the manuscript and claimed credit for the work?

In Sytsma and Livengood (2011), Jonathan and I argued that this phrasing is ambiguous, with some participants interpreting it from John’s perspective while others interpreting it from the narrator’s perspective. And we presented several different studies showing that when you disambiguate the question subtly along those dimensions you notably affect the answers of American participants. In addition, we failed to replicate the numbers that Machery et al. 2004 got for Westerners on our samples (across three studies we got 39.4% (B), 42.9% (B), and 39.7% (B), compared to 56.5% (B) in Machery et al. 2004, IIRC). Subsequent to this, much of the work done on the issue has used one of the disambiguations we tested (or language borrowed from it) — what we called the Clarified Narrator’s Perspective Probe — including the two papers you linked to above. The question for the Clarified probe reads as follows:

Having read the above story and accepting that it is true, when John uses the name “Gödel,” would you take him to actually be talking about:

(A) the person who (unbeknownst to John) really discovered the incompleteness of arithmetic? or

(B) the person who is widely believed to have discovered the incompleteness of arithmetic, but actually got hold of the manuscript and claimed credit

for the work?

This probe (and variations on it) has replicated well, including in Sytsma, Livengood, Sato, and Oguchi (2015), which tested a translation to Japanese and then a reverse translation to English. It is unfortunate, IMO, that Grau & Pury didn’t use the Clarified probe for their study, and I’m rather skeptical of the results because of it quite outside of the failure of replication of the demographic effect they look at. Would be interesting to test their hypothesis using revised materials. (Perhaps someone has done that? If not, if anybody would like to, flick me an email — would be happy to be involved in that!)

I should add here that I think the XPR project is fantastic and is well carried out. In fact, I’m about to leave to teach it in my x-phi class in just a few minutes! I just don’t think that much can be drawn from the few demographic effects tested.

Whoops, links to preprints of the two papers:

http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/5130/1/A_New_Perspective_Concerning_Experiments_on_Semantic_Intuitions.pdf

http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/11466/1/Reference_in_the_Land_of_the_Rising_Sun__PREPRINT.pdf

This comment from Justin is amazing. It’s filled with information I didn’t previously know and opens up a new hypothesis I hadn’t even considered. I had just assumed that the result from the replication project study was a type 2 error, but given what Justin says, it seems like that study might actually be giving us the right answer, at least on one very narrow and specific question. Taken as a whole, existing evidence certainly seems to suggest that there is a cross-cultural difference in intuitions about reference. Still, if Justin is right, it might be that the replication result is correct in telling us that this one specific experiment, using these precise materials, is not replicable.

I don’t work on this topic myself, and I’m not really qualified to assess this suggestion. I would love to hear what other people think.

Here is (finally!) the preprint of our meta-analysis of replications of Machery et al. 2004 (cross-cultural differences in intuitions about the references of proper names):

https://psyarxiv.com/ez96q