Ken Chung (1978 – 2017)

Ken Chung, a philosopher who taught at Western University, Ryerson University, the University of Guelph-Humber, and at Trent University, died this past Wednesday. He was 39 years old.

Chung received his PhD from Western University in 2010. His dissertation was on “the fact of reason” in Kantian moral philosophy.

A year and a half ago, Chung was diagnosed with Stage IV pancreatic cancer, and he started a blog to record his thoughts about it. In his last post, he announces his death, and writes, “He wished he had more time to think, to write, to read, to figure out what life was all about. But mostly he wanted more time to spend with his wonderful wife, Emma Abman, and to hang out with his family and friends. He considered himself to be, on the whole, a lucky man.”

The following is the text of his penultimate post, “Struggle“:

If you try hard at something but fail, you experience disappointment. And the harder you try, the greater the disappointment.

This is a lesson we learn when we’re young, but we spend the rest of our lives wrestling with its implications. How can we motivate ourselves to work really hard, when we know that we might fail? And the harder we work, the more bitter the failure?

Here are some ways that I have found to be promsing:

- Try to maximize the amount of work that you enjoy doing for its own sake, and minimize the work you do only because of its results.

- Try to find a way to love the process over the outcome.

- Try to accept the fact that success depends on factors outside our control, and try to allow only what is within our control — for instance, the efforts we make — to affect our state of mind.

- Try to see that we’re playing with odds here, and that even though we know that the harder we work, the greater the disappointment, greater too is the likelihood of success.

But despite all this, for me to do the hard work, I have to know that there is, at the very least, the possibility of success. It is hard to endure a struggle without at least the possibility of something good resulting from my efforts. To quote from Galatians: “And let us not grow weary of doing good, for in due season we will reap, if we do not give up.”

Here’s the thing about having terminal cancer. You will struggle but then you will die; there is no reward. There is nothing that I will reap in the end for all the efforts I make in dealing with this illness. It was always going to kill me. There is no great payoff in the end for fighting cancer bravely or with apparent wisdom. I will be dead. I will no longer exist to enjoy whatever gains there were to be had.

There is no rest either. We are fond of saying “rest in peace,” of imagining that people who die are finally allowed to rest their weary souls. We are fond of saying this even if we are atheists and believe that death is the end, that there is no person who persists after it. But how can something that does not exist rest? Do the flames rest when the fire is out?

So this is a struggle without a reward. Is this why I find it so fucking hard?

I know, though, that the struggle itself is not all dark. It’s still up to me to make an extra effort to enjoy what I can — to take an extra second to enjoy my coffee, to taste the sweet freshness in the fruits I can still eat, to cherish the warmth of friends and family, to write a word here and there.

Cancer, you will take everything from me eventually. But not yet, you fucking asshole.

You can read more of Ken Chung’s writing here.

I’m sorry not to have known him.

I was friends with Ken during the time he was completing his PhD at Western. We saw shows together at Call the Office. He gave me a copy of the Unicorns CD “Who Will Cut Our Hair When We’re Gone?” He brought kindness, depth, and charity to his conversations. In that way he embodied much of what is best about philosophy. I remember him being unwilling to accept that as humans we couldn’t aspire to overcome and be more than our nature. He was frustrated when we didn’t. Ken may not have believed that there is any moral injustice in his diagnosis “So there’s no moral failure in asking “Why me”. But there’s no answer either.”, but there is certainly a feeling of wrongness with it.

When I met him 15 years ago he was a wonderful person with an immense sense of style that attracted my friendship immediately. We went to figure drawing together sometimes. In his last months he encouraged me to start drawing again, and inspired me with his art. In the years I knew him he grew wiser, kinder and more full of love. He was a moral compass for me, and our discussions helped me to navigate living in this world as a better person. The world is impoverished by this loss; my heart also.

Thank you for recognizing his passing, Justin. I didn’t know Ken well but greatly appreciated his contributions as an instructor at Trent. Knowing about his diagnosis still didn’t convince me that he would have to yield eventually. It’s all difficult to accept, and the acknowledgements of others is helpful.

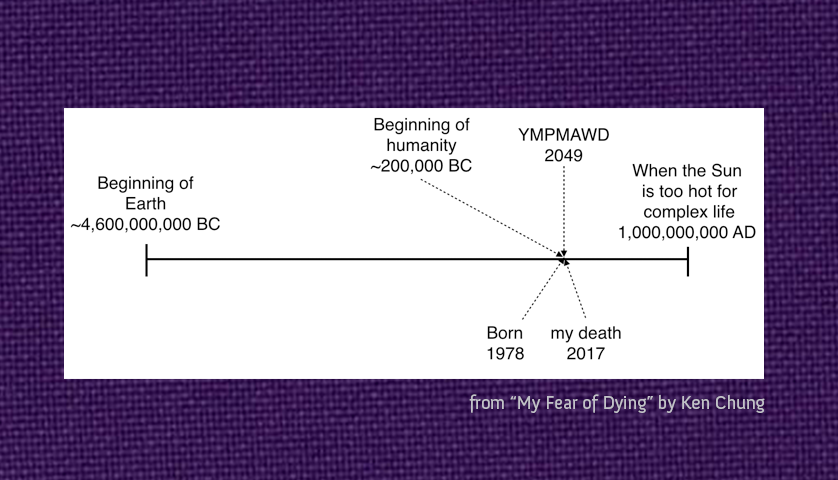

If you read nothing else today, please click on the timeline graphic above and read Prof. Chung’s “My Fear of Dying”. It is one of the most honest pieces of self-reflection on one’s mortality I’ve ever read, a 21st century Phaedo penned by Hemingway. I wish I had known him; I wish I could have thanked him for this.

I am so lucky that I was able to get to know Ken over the last three and a half years. Today I was with Ken’s wife, in-laws, and some close friends, sharing memories and grief, when the love of his life discovered this post. She was so moved to see him memorialized and shared here. Thank you for honouring Ken and his writing, which represents so well his thoughtful, contemplative, rich mind and his heart of gold. I wish he had more time, I wish we had more time with him, and I wish he could know the appreciation that people are feeling for his essays.

I taught Ken Chung’s essay, “Is Dying a Transformative Experience?”, to 90 students at Trent University on the day that Ken died, without realizing that he had died that day. The discussion that that essay produced was by far the best discussion in my course so far, and one of the best discussions that I have had with students in my eight years of teaching Philosophy. Students rightly observed that Ken was like a contemporary Michel de Montaigne, using philosophy as a way to learn how to die. They pointed out that Ken was completely unlike most of the characters in Tolstoy’s “Death of Ivan Ilyich”: whereas Ilyich, his family, and his colleagues were too self-centered or too cowardly to face death straight on, the students found that Ken’s essays demonstrated enormous courage, humanity, selflessness, and honesty. About a dozen students have announced to me that they were so moved by Ken’s essays that they will write their first essay in my course on Ken Chung. I highly recommend Ken’s essays for courses on a wide range of subjects, from the Meaning of Life, and Death, to a variety of Ethics courses.

I didn’t know Ken very well, though we were grad students together at Western (we were in different years), and though we were colleagues at Trent (he taught at a different campus). But I learned about his diagnosis early on, and I was a regular reader of his blog for a little over a year. A few days before he died, I reached out to Ken by email to tell him that I had been reading his essays and that I admired them. I asked for his permission to teach them in my courses, and he wrote me a very kind email that included that permission. Since Ken and I were not that close, I assume that the permission he gave to me applies to anyone reading this comment. It would be a very good thing if those essays were published as a book…