A Semantic-Network Approach to the History of Philosophy (guest post by Mark Alfano) (UPDATED)

What can we learn from constructing semantic networks of familiar works in the history of philosophy? A fair amount, according to Mark Alfano, a philosopher at Delft University of Technology and Australian Catholic University, as he explains in the following guest post*—such as which concepts tend to get more attention from readers than might seem appropriate given their surprisingly smaller roles in the text, or how an author’s views change over time, for example. It’s an unusual method for a philosopher; readers should feel free to ask Professor Alfano questions about his approach in the comments.

A version of this post was also published at Dr. Alfano’s blog.

(For further details, see the update to this post.)

A Semantic-Network Approach to the History of Philosophy

Or, What Does Nietzsche Talk about when He Talks about Emotion?

by Mark Alfano

Have you ever read an article that makes claims like, “Plato often talks about W” or “Kant typically associates X and Y” or “In his early work, Nietzsche seldom engages with Z”? I have. When I read these claims, I want to ask simple-minded questions like, “How often?” and, “What do you mean, ‘typically’?” and, “How seldom is seldom?” If these sorts of claims have any evidential value, it should be possible to verify or falsify them. Or—to turn the conditional around—if it’s not possible to verify or falsify them, then these sorts of claims have no evidential value.

As preparation for my in-progress book on Nietzsche’s moral psychology, I’m developing a methodology for quantifying, mapping, and analyzing the concepts used in philosophical corpora. My hope is that this methodology will make it possible to answer the simple-minded questions mentioned above, and that answering these questions systematically will lead to new insights. Furthermore, if my approach is on the right track, it should be fairly easy to retool it for the study of corpora by other philosophers, as well as corpus comparisons between (groups of) philosophers.

The three questions I started with ask about prevalence, association, and change. If we cut up a philosopher’s corpus into chunks and label each chunk based on its semantic content (i.e., whether it contains an expression for concept W, X, Y, and/or Z) as well as bibliographic information (i.e., which book it’s from and when it was published), it becomes possible to answer these questions. A concept is prevalent to the extent that it shows up in a large proportion of passages. It’s associated with another concept to the extent that it’s more likely than chance to be present in a passage when the second concept is present. A concept becomes more prevalent over a philosopher’s career to the extent that it shows up in higher proportions of passages over time.

How big or small a passage should be depends on the philosopher in question. It’s natural to make the chunks sentence-sized, since sentences express whole thoughts. It’s also natural to make the chunks paragraph-sized, since paragraphs express more complex thoughts and arguments. In the case of Nietzsche, a handy size is the numbered/titled section. At least after the Untimely Meditations (1873-76), his sections tend to be roughly the same length (half a page to a couple of pages), and they’re the standard unit of reference in the literature. For Plato and Aristotle, Stephanus pagination and Bekker furnish natural units of analysis. It’s a bit arbitrary, but the basic idea is clear.

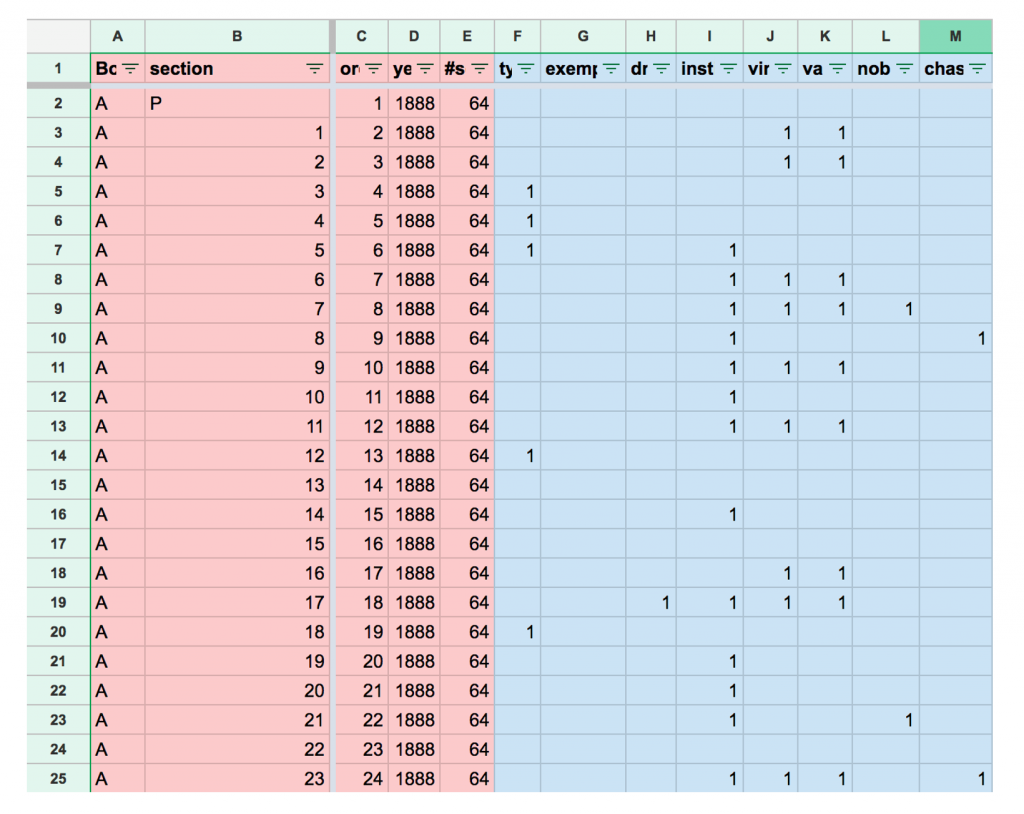

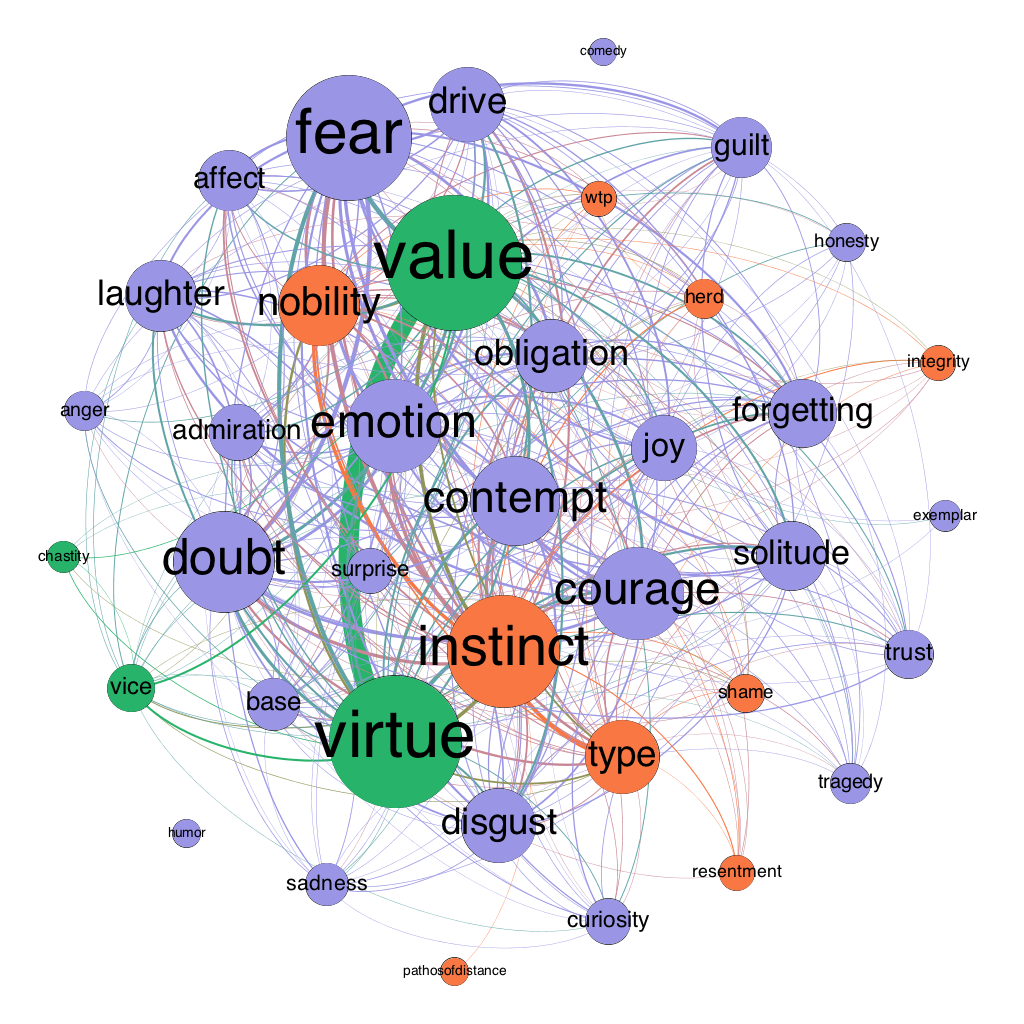

In labeling sections, it helps enormously to have a searchable digital version of the text. Otherwise, one simply has to read everything by the philosopher under study from cover to cover, keeping a weather eye out for every concept of interest. That’s difficult, stressful, and time-consuming. Fortunately, for many prominent philosophers, searchable digitizations exist. In the case of Nietzsche, I was able to consult the Nietzsche Source, which I used to find every passage in which each of the concepts in Table 1 occurs.

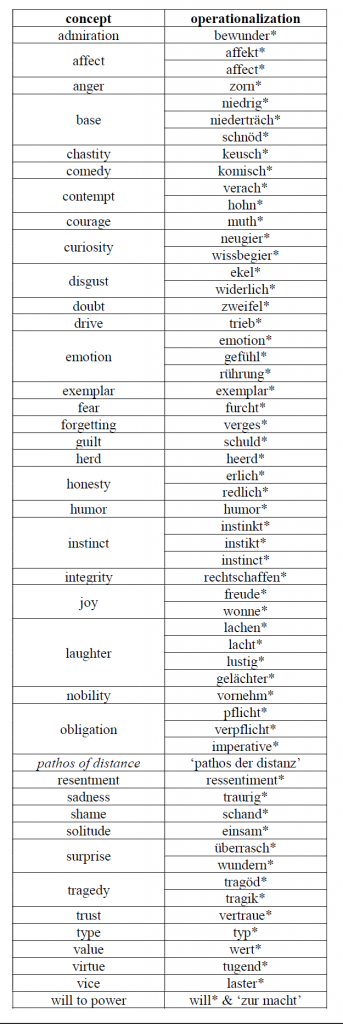

Of course, Nietzsche wrote in German, so I couldn’t just search for the concepts directly. Instead, I had to operationalize each concept with a (disjunction of) word stem(s). Appending an asterisk to a search query returns every passage in which at least one word that begins with the word stem occurs. This is likely to return a few extraneous passages (false positives) and miss a few passages (false negatives), but it’s still highly reliable and reproducible.

I entered identifying information about each of the 3327 passages in Nietzsche’s published and authorized manuscripts into a spreadsheet, then dummy-coded each passage for the presence or absence of each of the concepts of interest. A representative piece of this spreadsheet is displayed in Figure 1.

The section of data pictured in Figure 1 is the preface and first 23 sections of The Anti-Christ, which was published in 1888 and has 64 total sections. Sections 1 and 2 refer to both virtue and value, but not to type or drive. Section 7 refers to instinct, virtue, value, and nobility. Prevalence within a book or within the whole corpus can be calculated by summing a column. For example, there are 152 passages that refer to drive and 303 passages that refer to virtue. Overall, there are 4439 total references. Co-occurrence of a pair of constructs within a passage is a bit more complicated: a pair of constructs co-occur when the columns associated with both constructs have a ‘1’ in the same row. Since there are 39 constructs in this dataset, there are 741 potential co-occurrence pairs or edges (38+37+…+1).

For the book, I’ll use this data structure to construct timelines, treemaps, section-by-section guides of each book, and semantic network visualizations, as well as to calculate inferential statistics such as Fisher’s exact test. In this post, I’m just going to show some of the network visualizations. I built these visualizations by converting the data to an adjacency list, then uploading the list to Gephi, an open-source network visualization application. In previous work, I’ve collaborated with Andrew Higgins and Jacob Levernier to map psycho-semantic networks of values, virtues, and constituents of wellbeing extracted from obituary texts.

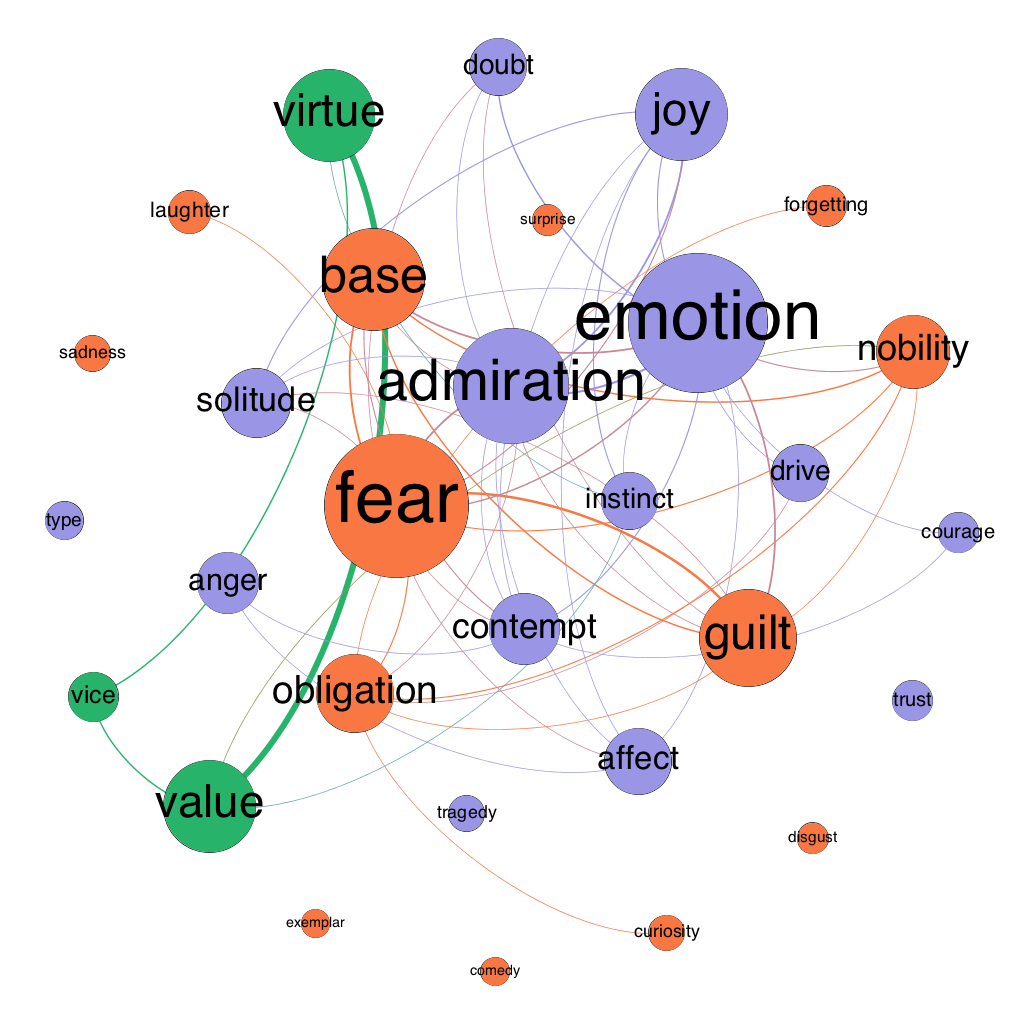

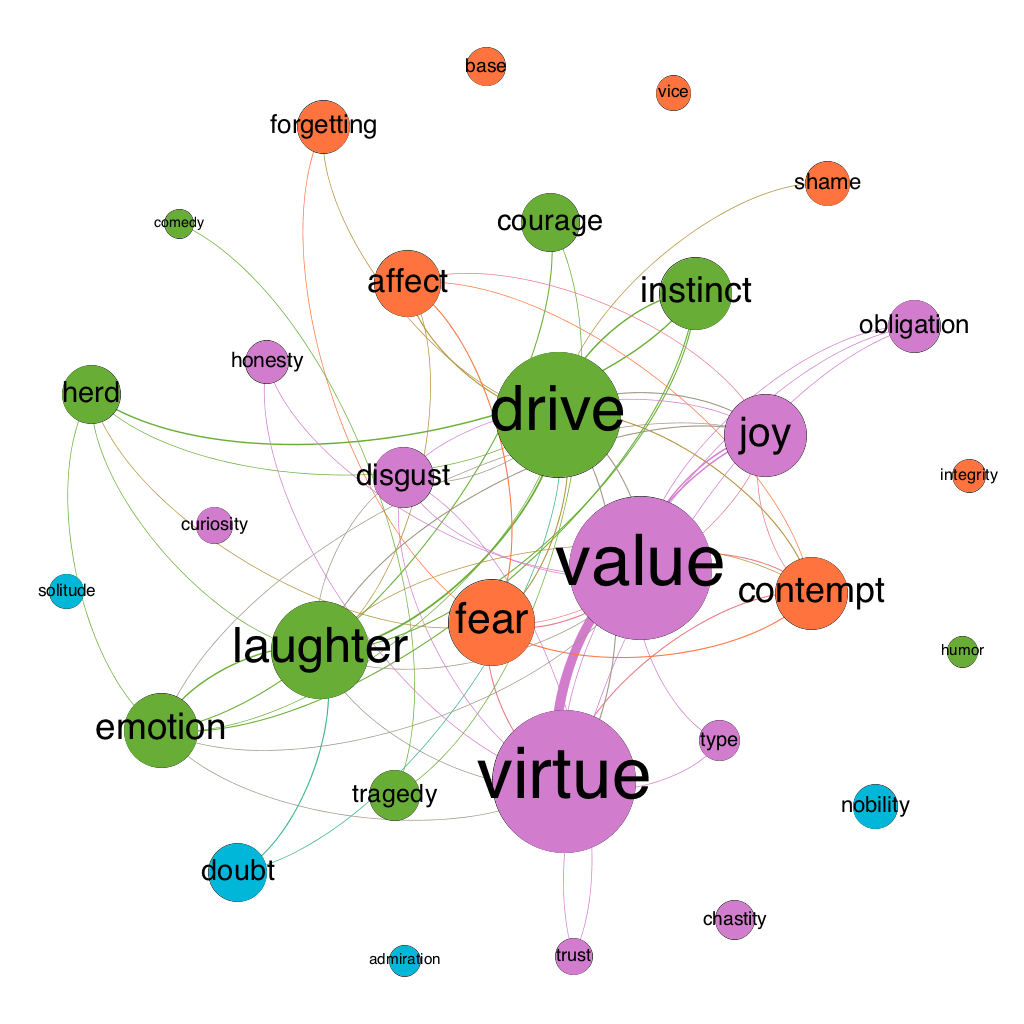

The current project is similar, but, instead of working from obituaries to map laypeople’s normative structures, I’m working from Nietzsche’s writings to map his moral psychology. I made one overall map based on all of the data (Figure 2), as well as maps associated with each book. Nietzsche had a habit of republishing his books with new prefaces and new sections (e.g., Human, All-too-human and Gay Science); in those cases, I made a map of both the original book and the revised book. This resulted in 23 maps, starting with The Birth of Tragedy in 1872 and ending with Ecce Homo in 1889.

Here is how to read such a map:

- The size of a node indicates its “weighted degree.” This is the sum of all of the co-occurrences of the concept in question. For example, suppose X occurs in three separate passages of a book. In the first passage, it co-occurs with Y but no other concept under study. In the second passage, it co-occurs with Y and Z but no other concept under study. And in the third passage it again occurs with Y but no other concept under study. X would then have a weighted degree of 4 (3 from Y plus 1 from Z). Size is thus a rough indicator of connectedness and therefore of prevalence in a moral psychological context.

- Edge width directly indicates weight: the wider an edge between a pair of nodes, the more frequently the concepts associated with those nodes co-occur. To clean up the “hairball” effect that emerges from having too many overlapping edges, I also dropped edges with low weight (sometimes just weight 1, sometimes 2 or 3—it’s a bit arbitrary, but the idea is to cut enough noise to make the graph legible to the eye).

- The color of a node indicates its membership in a “community” or modularity group. The math here is a bit hairy, but the basic idea is that nodes are classed into the same community with other nodes that they tend to co-occur with, and into a different community from nodes that they tend not to co-occur with.

- Edge color is determined by the nodes the edges connect. If both nodes are blue, the edge will also be blue; if one is blue and the other orange, the edge will fade from blue to orange.

- Finally, the position of a node is determined holistically based on three forces: 1) all nodes are attracted to the center of the graph, 2) all nodes repel each other, and 3) a node attracts other nodes based on the weight of the edge connecting them.

There are three modules in Figure 2: 1) a group of (mostly) emotions in blue, 2) a smaller group of normative statuses in green, and 3) a group of psycho-social constructs in orange. Among the most prominent emotions are doubt, contempt, disgust, trust, sadness, joy, guilt, and curiosity.

You might find this map a bit surprising. When we teach Nietzsche to our students, we tend to focus on resentment, leaving out most of the other emotions that he actually talks about. My hunch is that this is because most translations of Nietzsche into English leave ‘ressentiment’ in the French and always italicize it, despite the fact that Nietzsche only italicizes it twice and only refers to it in a couple dozen passages. This distracts readers and leads them to fetishize resentment and ignore the other emotions.

You might also strain your eyes looking for ‘will to power’—another Nietzschean construct that gets a lot of airtime despite playing only a modest role in his moral psychology. In Figure 2 it’s the little node between ‘value’ and ‘guilt’ (abbreviated ‘wtp’). Again, my guess is that because Nietzsche sometimes puts this striking phrase in italics, it’s received an undue amount of attention in the secondary literature. What Nietzsche actually talks about when he engages with moral psychology, though, is concepts like virtue, value, instinct, fear, doubt, emotion, contempt, courage, nobility, disgust, laughter, solitude, drive, and forgetting. Some of these concepts receive adequate attention in the secondary literature, but many don’t. Just to single out a few, check www.philpapers.org for contempt, courage, and solitude.

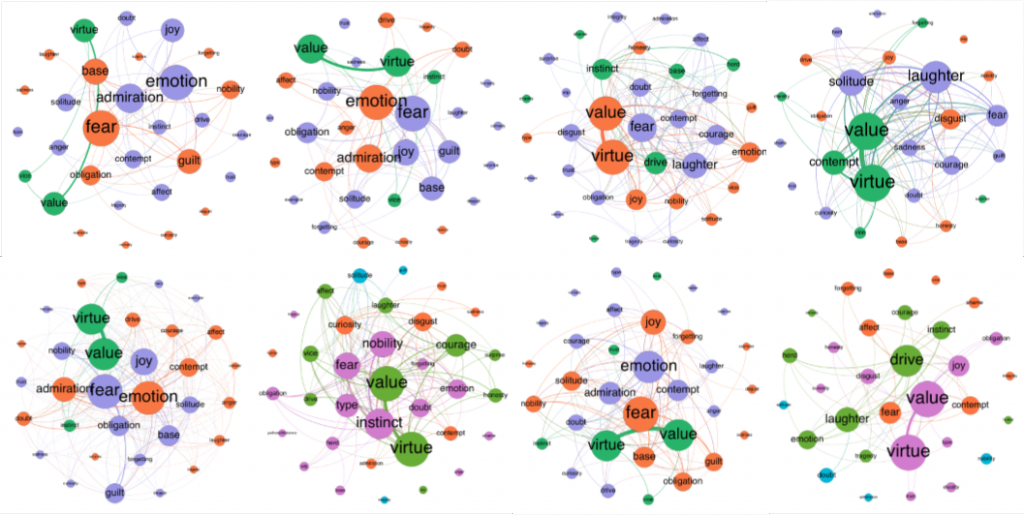

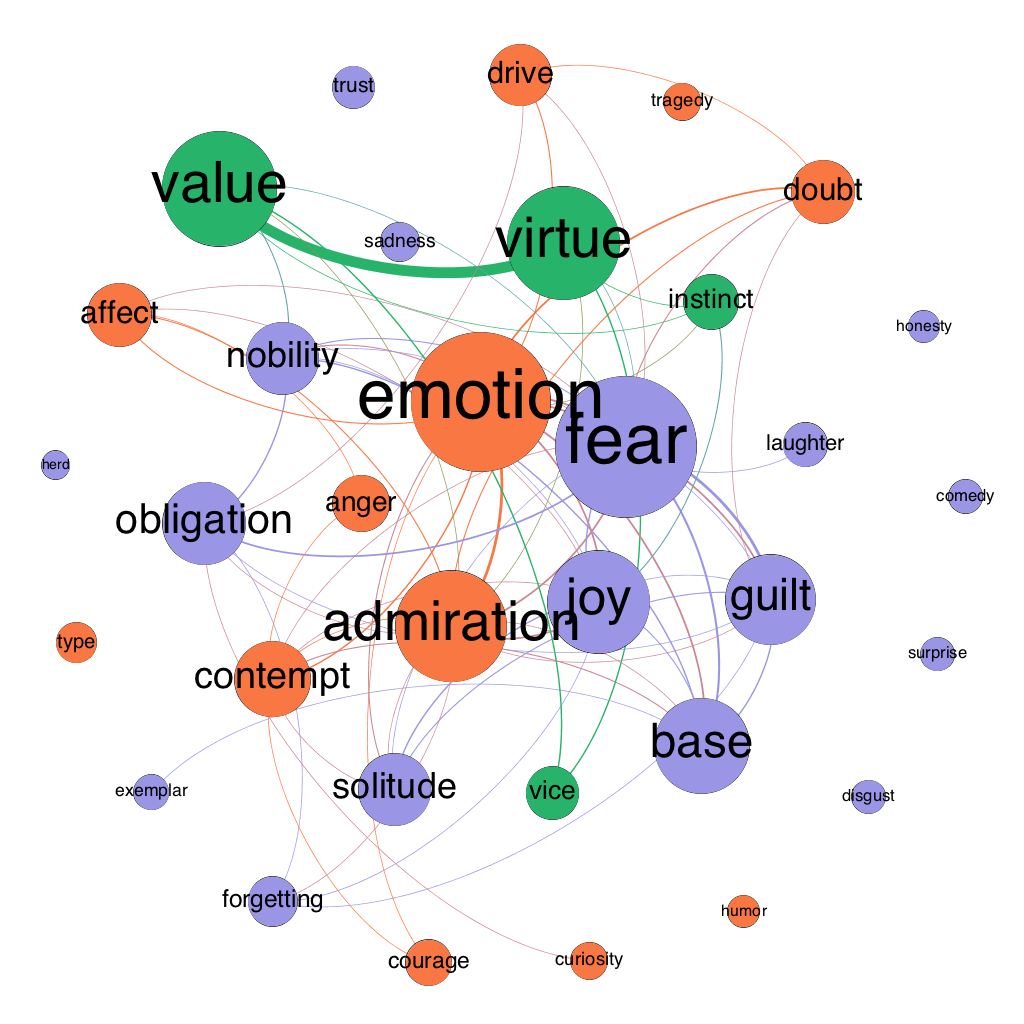

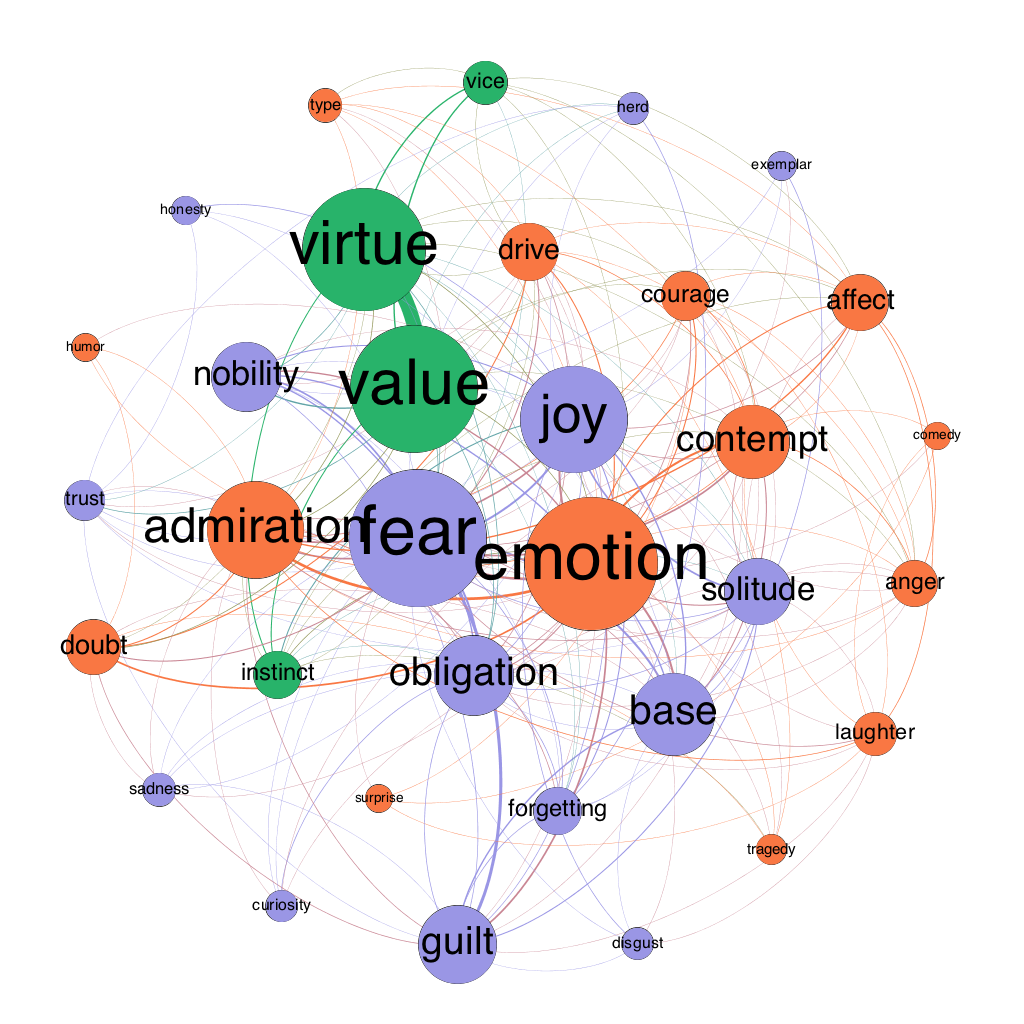

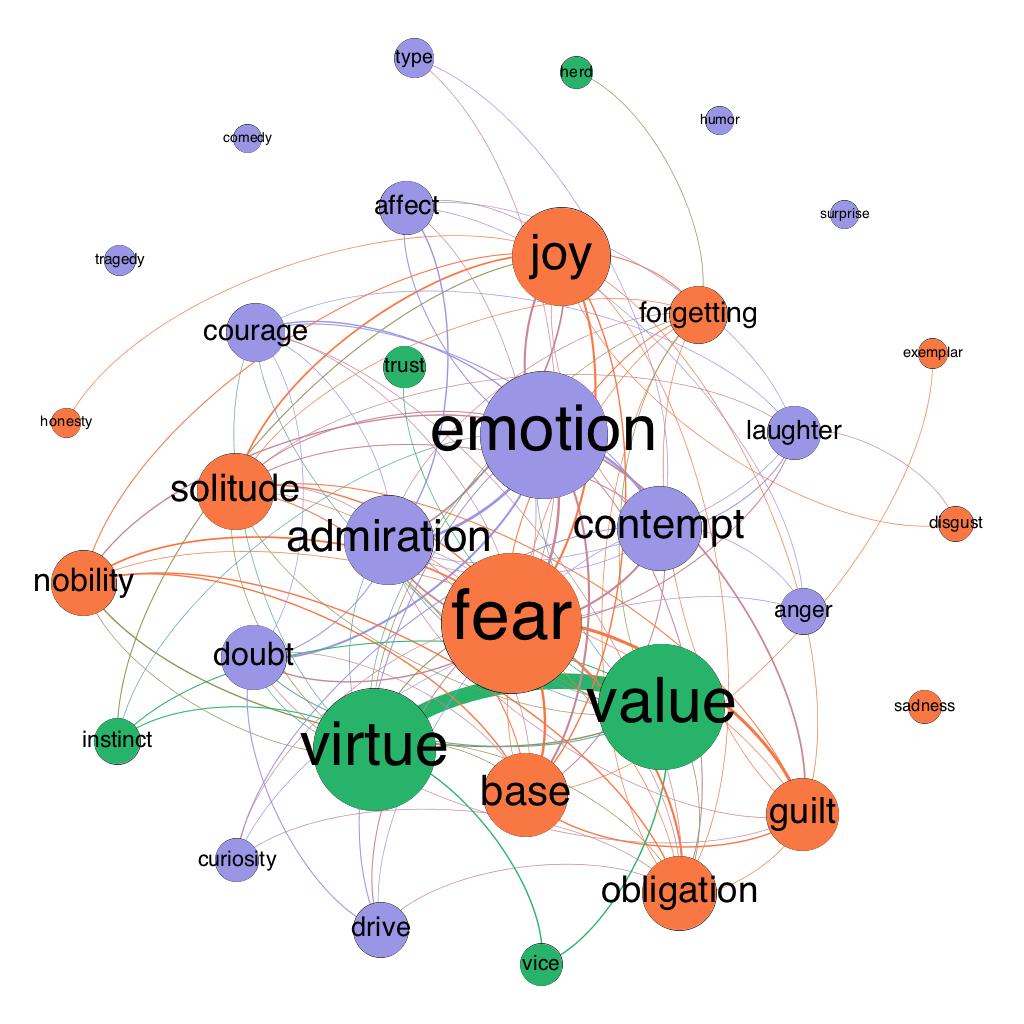

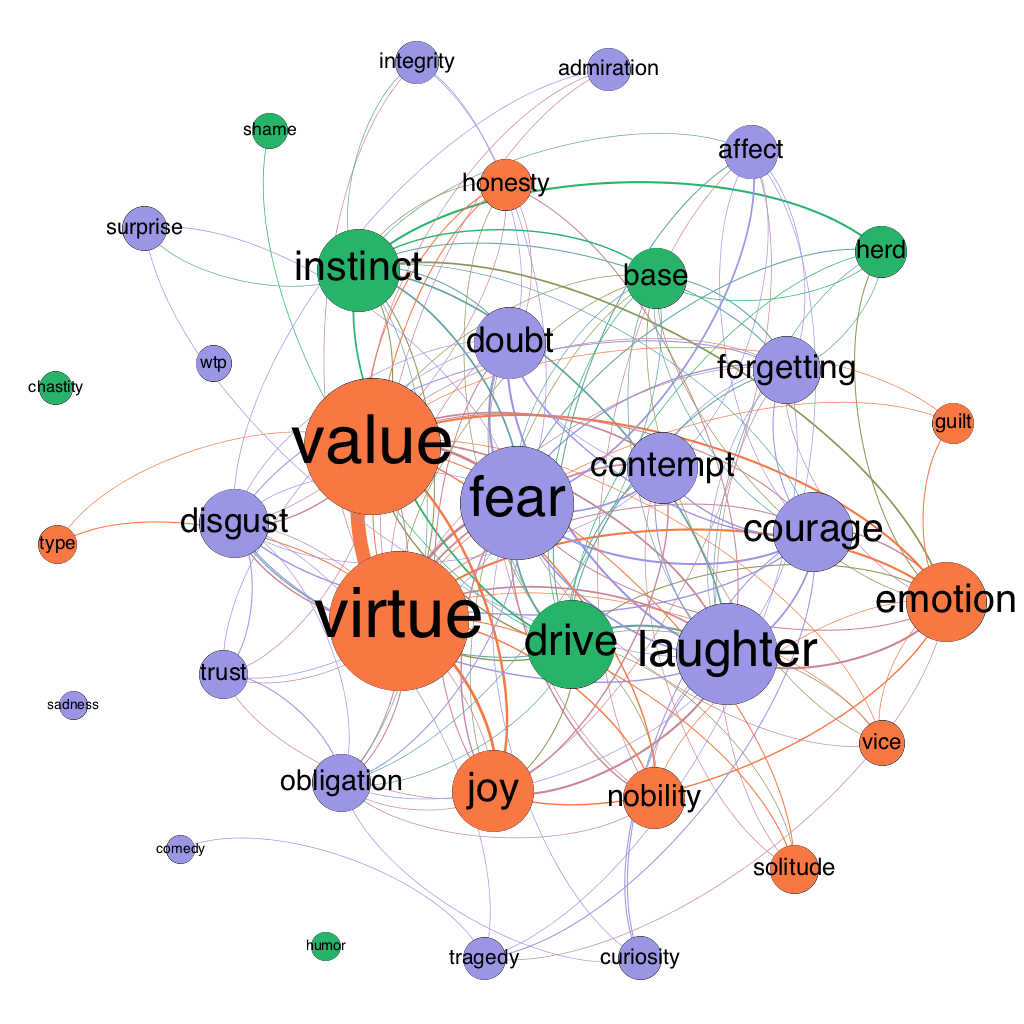

To see how Nietzsche’s views change over time, we can look at all of the maps, but it may be even more helpful to compare maps of his significantly revised books. Figures 3-6 show Human, All-too-human as it existed in 1878, 1879 (with the addition of “Assorted Opinions and Maxims,” 1880 (with the addition of “The Wanderer and His Shadow”), and 1886 (with the addition of prefaces for both the original book and Assorted Opinions and Maxims). Figures 7-8 show The Gay Science in 1882 and 1887 (with the addition of book 5 and a new preface).

These progressions suggest a few observations about Nietzsche’s changing positions.

Start with Human, All-too-human. First, virtue and value move from the periphery to the center, and their node sizes increase, indicating that Nietzsche becomes more interested in these concepts over time. Second, obligation shrinks and moves to the periphery, indicating that Nietzsche is moving from an ethic of rights and duties to an ethics of virtue. Third, drive and instinct start in the same modularity class but show up in different modularity classes in all three of the updated versions of the book. This suggests that Nietzsche may not use them interchangeably (a bone of contention in the secondary literature).

Turn now to Gay Science. While drive and instinct are in the same modularity class in both versions of this book, there are other interesting changes. First, whereas fear is by far the most prominent emotion in Human, All-too-human, it is significantly demoted in Gay Science, where it is sits side-by-side with disgust, joy, contempt, and doubt. This suggests that Nietzsche moves from a moral psychology centered on the fear of an individual in a state of nature in Human, All-too-human to a moral psychology that also makes a place for hierarchies maintained by contempt and disgust, as well as the skeptical epistemic emotion of doubt. Second, laughter plays a much larger role in Gay Science, which should be unsurprising given the title of the book. Laughter plays an even larger role in Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1885 edition, Figure 9), which is often thought of as a ponderous book even though it’s full of giggles.

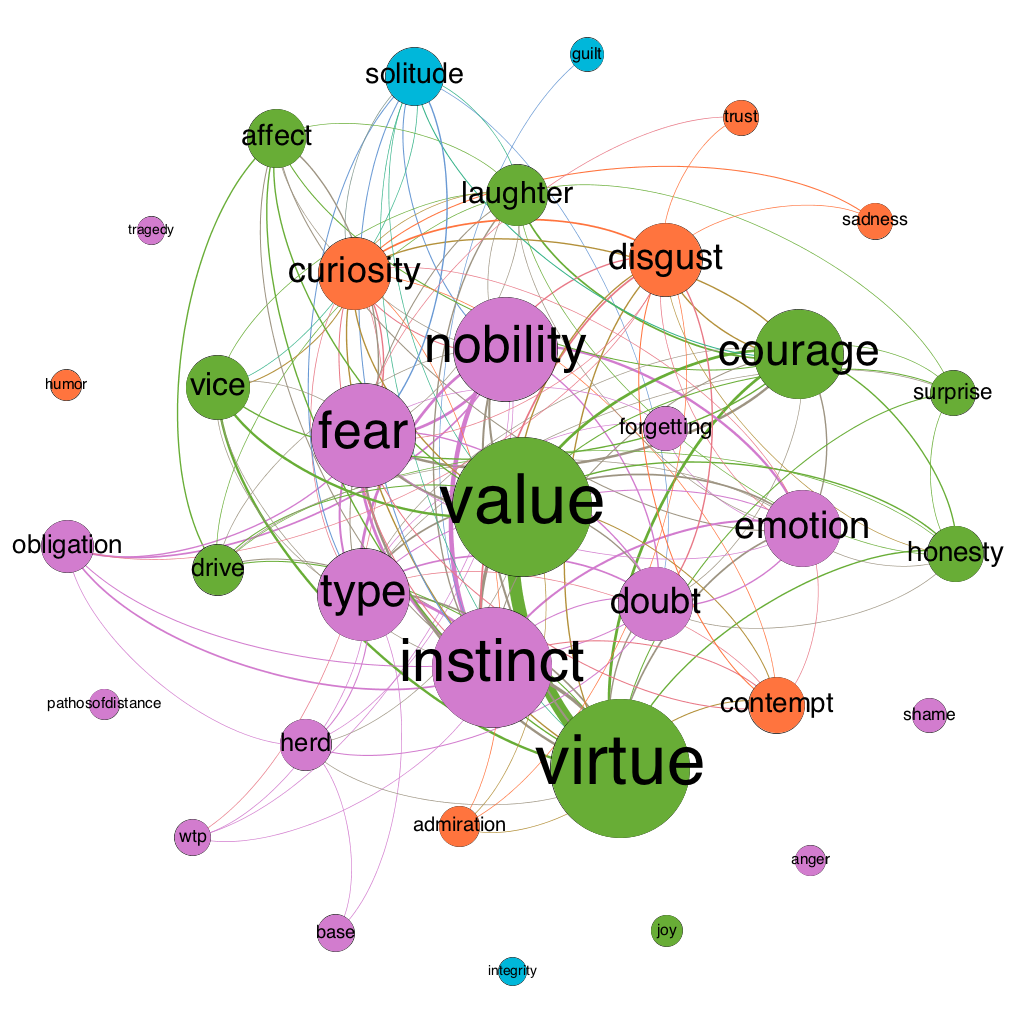

I’ll end with my favorite book of Nietzsche’s: Beyond Good and Evil (Figure 10).

This map once again places drive and instinct in separate modularity classes. It also continues to give a major role to the emotion of fear while contextualizing it with other emotions such as contempt, disgust, curiosity, doubt, surprise, and—to a lesser extent—admiration, sadness, trust, and guilt. Will to power plays a minor role, and resentment is completely absent.

A digital humanities approach like the one on offer here doesn’t answer all of the questions we might have about Nietzsche, but it does help to answer some of them and suggests under-explored lines of inquiry. I hope that other researchers find it useful and that some will be inspired to employ these methods in their own work—whether on Nietzsche or on other philosophers.

UPDATE (7/31/17): Some more detail:

Thank you for this wonderful service to Nietzsche scholarship!

I’m sure this is a very helpfull and effective approach for a historical perspective on philosophy. But I think if a sentence reads “Nietzsche often talks about X” this formulation is used as a justification to talk about X. It does not matter if that sentence has evidential value, hopefully it has a valueable content! And isn’t it true that some of the most interesting and thought-provoking passages tend to be at the periphery of a philosopher’s work?

Hi Pablo, and thanks. What I was trying to say is that if you use “Nietzsche often talks about X” to justify talking about X, then it should be verifiable that Nietzsche in fact does talk about X often. If it’s just code for “I want to talk about X in Nietzsche,” then people should just be honest and admit that that’s what they mean.

On your other point: I think of the prevalence, association, and change statistics as a baseline for the secondary literature. Absent explicit arguments for focusing on some concept or connection, the literature as a whole should resemble what’s actually in the texts. As you say, there may be exceptions at the periphery. It’s important, though, to recognize that they are exceptions and give reasons for thinking them exceptional.

Suffering, cruelty, responsibility, rights, privilege/rank, justice, revenge, conscience, consciousness…? I mean, fair enough, it’s fine to look for confirmation of *your* interpretation of Nietzsche, but I’m worried that virtue stands out so much because you’re downplaying some other weighty factors.

Thanks! The selection of constructs is a difficult matter, as you point out. I don’t want it to be idiosyncratic, so this kind of feedback is very helpful. Rights are already indirectly included via obligation, and privilege/rank via pathos of distance. Still, I’ll add these concepts.

I added your suggestions, Nick, as well as a couple others (life and health).

Link: http://www.alfanophilosophy.com/dh-nietzsche/

Conscience was a good lead, along with justice and revenge. Virtue still running the show, though.

This looks amazing, Mark, thanks for your work on this! In addition to improving research Nietzsche, this method promises to bring both insight and added rigor to the study of the history of the discipline more generally.

Thanks, John!

While it was long before my time and I’m not especially familiar with it, this reminds reminds me of work that Alastair McKinnon did on Kierkegaard’s works in the 70s using statistical analysis. I imagine there are some differences in the methodology. For example, I think it involved statistics regarding the of occurrences of certain words rather than concepts and I don’t know if he looked at co-occurrences in a manner narrower than within a certain work. But his work might be of interest to you due to this methodological similarity, as well as some of the discussion that happened around that time about the limitations or problems with this approach to analyzing a philosopher’s corpus (I know there was a fair bit of back-and-forth in the Kierkegaard newsletter on this at the very least).

Thanks — I’ll track down this stuff. If you happen to have it electronically, feel free to email it to me or post a link in the replies.

I think the core of McKinnon’s work is in his “Computational Analysis of Kierkegaard’s “Samlede Vaerker” which is something like four volumes and Khan has a book “Salighed As Happiness?: Kierkegaard on the Concept Salighed.” Below are links to various electronically accessible publications by these two authors that I was able to dig up that use or discuss the use of computer assisted statistical analysis:

KIERKEGAARDIANA

McKinnon has some pieces published in Kierkegaardiana which use his statistical analysis and can be found here for free:

https://tidsskrift.dk/kierkegaardiana/issue/archive

He has papers in issues 7, 9, 10, 11, 16, 20 and 22 and Khan has a paper in issue 12 (when you click on an issue, just click again on the cover and it will take you to a table of contents).

MISC. JOURNALS

https://www.pdcnet.org/collection/show?id=wcp15_1975_0006_0811_0816&file_type=pdf

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00201748408602021

https://www.pdcnet.org/collection/show?id=intstudphil_1979_0011_0000_0165_0173&file_type=pdf

https://www.pdcnet.org/collection/show?id=thought_1980_0055_0003_0333_0345&file_type=pdf

THE KIERKEGAARD NEWSLETTER

Starting on p. 15 is a very short piece by McKinnon on trends in the collected works:

https://wp.stolaf.edu/kierkegaard/files/2014/03/Newsletter38.pdf

Starting on p. 7 Khan has some discussion of the electronic collection of Kierkegaard’s works at McGill and the use of computational analysis on this collection:

https://wp.stolaf.edu/kierkegaard/files/2014/03/Newsletter30.pdf

Starting on p. 3 is a review of a book by Khan that employs computer assisted analysis of the concept of Salighed and a reply by Khan follows:

https://wp.stolaf.edu/kierkegaard/files/2014/03/Newsletter16.pdf

Whoops, I edited out a brief bit about how I had forgotten that there was another scholar, Abrahim H. Khan, who has done similar work on Kierkegaard as well, and forgot to replace it (so that’s who the ‘Khan’ is that gets mentioned a couple of times).

I wonder what Nietzsche would say about this approach. Any Nietzsche scholars care to opine? Would it matter if one’s philosophical practice is in some ways at odds with the teachings of the philosophy one studies?

Uhhh… he was a philologist. And I’m a Nietzsche scholar.

Perhaps the relevant text here is GM preface, 8:

“An aphorism, properly stamped and moulded, has not been ‘deciphered’ just because it has been read out; on the contrary, this is just the beginning of its proper interpretation, and for this, an art of interpretation is needed. In the third essay of this book I have given an example of what I mean by ‘interpretation’ in such a

case: – this treatise is a commentary on the aphorism that precedes it. I admit that you need one thing above all in order to practise the requisite art of reading, a thing which today people have been so good at forgetting – and so it will be some time before my writings are ‘readable’ –, you almost need to be a cow for this one thing and certainly not a ‘modern man’: it is rumination …”

Whether or not this provides support for Alfano’s project is a matter of… interpretation.

Oh right, I forgot to mention: moo. Now do the phenomenologists understand?

dear mark-

This is an interesting piece and I’m very much in sympathy with your goals, having done similar work myself in different contexts. Thanks for sharing it. I have a couple of questions-

— what granularity did you set modularity to? The size of the groupings makes me think you used a value of 1.0. Did you experiment with smaller values, and did you discover thereby either which communities are more robust or which unexpected sub-groups break out?

— how did you derive the table of concepts, and how did you derive your table of operationalizations? You say that you have few false +/-; what degree of confidence can you attach to that statement? I’m not in your field, so this might be a uncontroversial table and I might simply be ignorant.

— could you do a PCA section by section and compare results? As a literature scholar I wonder how much N was referential (ie using das, der, die, es, etc) and how nominal (consistently using nouns). A carefully stoplisted PCA or topic model might uncover this, and make for an worthwhile comparison to these graphs. (This kind of analysis would pull out components missed in the table of concepts, too.)

— do these graphs and their points of dis/continuity which each other allow you to construct a positive arc of the history of N’ s moral philosophy, or only to critique existing N pedagogy? The second is obviously a worthy goal too, but the 1st is bigger.

–Which concepts show up with high clustering or betweenness? Can you leverage those findings to make more jointed arguments about the etiology of 2ndary lit on N and about the true state of his argts?

Lots of other things, but I’ll stop there. Thanks for sharing.

Claude

Hi Claude: glad you found it interesting!

1) Yes, I kept the modularity as close to 1 as possible while aiming for three clusters across all graphs. When I publish this stuff, it’ll probably have to be grayscale, so three modules is the most I can reasonably expect to distinguish. That said, your question is quite sensible. I’ll have to play around with the settings to see what pops out.

2) The list of concepts was built up in three ways. First, I included all the concepts that I’d already worked on when studying Nietzsche’s moral psychology. Second, I consulted the abstracts and keywords of the first couple hundred entires on Nietzsche and moral psychology at http://www.philpapers.org. Third, I asked around and got feedback from other Nietzsche experts.

3) For the operationalizations, I went through a process of translation and back-translation for all of core constructs, then checked the Nietzsche Source for whether he used any of the German expressions. Then I looked at a few dozen passages per concept to make sure that the result was not a false positive (haven’t found a single exception so far). False negatives are harder; I searched digitized English translations for the core concepts and checked whether the passages that contained them were already in my database. I found a few false negatives in this way. One source is Nietzsche’s archaic spelling. For example, he sometimes writes ‘Affect’ but sometimes writes ‘Affekt’, and he sometimes writes ‘Instinct’ but sometimes writes ‘Instinkt’. He also sometimes uses expressions that are clearly related to a core construct without using one of the operationalizing terms. My favorite examples are the three passages in Daybreak (166, 203, 206) where he onomatopoetically spits out ‘pfui!’ If I had to put numbers on my confidence, I’d say there are at most 5% false positives (probably closer to 1%) and at most 10% false negatives (probably closer to 8%).

4) Yes, it should be possible to do a principle components analysis. I haven’t done Moretti-style PCA yet, but agree it would be a nice comparison. You’re thinking of something like this? https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/06/upshot/the-word-choices-that-explain-why-jane-austen-endures.html

5) On the change-over-time question: yes, I agree it would be especially interesting to establish answers to questions like this. The closest I’ve come so far is the arc through the four versions of Human, All-too-human, where virtue/value push out obligation. I’m going to be puzzling over all of the graphs in the coming weeks and hope to have some tentative conclusions by the end of summer. Part of the difficulty is that these kinds of descriptive analyses don’t make it clear whether a difference between graphs is a significant difference. For that, one needs inferential statistics, but Gephi can’t compute inferential statistics. There are some network-analysis packages in R, though, that can do this. They’re mostly developed by Borsboom, Epskamp, and Borkulu.

6) I haven’t gotten to this yet, but just now checked PageRank for each of the nodes in a slightly expanded network (added 8 more concepts). The highest-ranked nodes are (in order) life, conscience, value, virtue, fear, instinct, doubt, emotion, courage, contempt. I need to think more about this question before answering in more detail, though.

Nifty! I take a somewhat similar approach in my ‘David Lewis and the Kangaroo: Graphing philosophical progress’ (benj.ca/dklkanga.pdf). That is based on autocitation data, with nodes as publications and edges as citations or cocitation-occurrences; obviously the level of resolution is lower, while there is a more direct representation of temporal evolution. It would be cool to see the results of your approach to DKL, or to explore strategies for overlaying the publication- and word-analyses. Nietzsche is probably not amenable to autocitation analysis!

Cool, thanks! Agreed about Nietzsche and citation….

It’s kinda tricky to do the same kind of word-analyses with papers because they’re so much bigger and not divided into nice little chunks the way Nietzsche’s texts are. I guess you could split at the paragraph level. Or just associate each paper with its keywords.