Do Philosophers Care Too Much About Fallacies?

I used to teach a course in critical thinking at Ghent University. As behooves a good skeptic, I first presented my students with the usual laundry list of fallacies, after which I invited them to put the theory into practice. Take a popular piece from the newspaper or watch a political debate, and try to spot the fallacies.

I no longer give that assignment.

My students became paranoid! They began to see fallacies everywhere. Rather than dealing with the substance of an argument, they just carelessly threw around labels and cried “fallacy!” at every turn. But none of the alleged “fallacies” they spotted survived a close inspection…

Here’s the nub of the problem: arguments that are deemed ‘fallacious’ according to the standard approach are always closely related to arguments that, in many contexts, are perfectly reasonable. Formally, the good and bad ones are indistinguishable. No argumentation scheme can succeed in capturing the difference, separating the wheat from the chaff.

That’s Maarten Boudry (Ghent), arguing against the value of emphasizing fallacies (e.g., ad hominem, ad ignorantiam, ad populum, begging the question, post hoc ergo propter hoc, affirming the consequent, argument from authority, and the like).

In a post at his blog (which will be published as an article in Skeptical Inquirer), he summarizes an argument from a paper he co-authored with Fabio Paglieri and Massimo Pigliucci, called the “fallacy fork,” which poses a dilemma for fallacy fans.

The first horn of the dilemma, or prong of the fork, is that if we’re going to be strict about it, in order for a piece of reasoning to suffer from one of the typical fallacies, the reasoning must be explicitly or implicitly in a tightly deductive form, and, as it turns out “we hardly ever find such clear-cut errors, presented in deductive form, in real life.”

The second prong is this: if we’re not going to be strict about it, then we need to formulate our fallacies in a way such that they apply to more than just instances of tightly deductive reasoning; but once we add “some qualifiers and nuances” to capture more instances of reasoning, it is no longer clear that those instances of reasoning are fallacious.

Here’s an example of how the fallacy fork works, with the post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy:

Every skeptic is familiar with the saying: correlation does not imply causation. To think otherwise is to commit the post hoc ergo propter hoc (or cum hoc) fallacy. The website Spurious Correlations has collected some outrageous examples, with fancy graphs: there is a clear correlation between margarine consumption and divorce rates, and between the number of people who drowned by falling in a pool and the number of films featuring Nicholas Cage (per year). Is there a mysterious causal relationship between these events? If I was ill yesterday and feel better today, to which of the myriad possible earlier events should I attribute my improved condition? That I had cornflakes for breakfast? That I watched a movie with Nicholas Cage? That I was wearing my blue socks? That my next-door neighbor was wearing blue socks?

Not even the most superstitious person believes that correlation automatically implies causation, or that any succession of two events A and B implies that A caused B. There are just too many things going on in the world, and not enough causal connections to account for them. In its clear-cut deductive guise, the post hoc ergo propter hoc inference is a fallacy, to be sure, but hardly anyone makes it in real life. This is the first prong of the Fallacy Fork. So what about the kind of post hoc arguments that people do use in real life? (Pinto 1995) As it turns out, many of those are not obviously mistaken. It all depends on the context.

Imagine you eat some mushrooms you picked in the forest. Half an hour later you feel nauseated, so you put two and two together: “Ugh. That must have been the mushrooms”. Are you committing a fallacy? Not as long as your inference is merely inductive and probabilistic. Intuitively, your inference depends on the following reasonable assumptions: 1) some mushrooms are toxic 2) it’s easy for a lay person like you to mistake a poisonous mushroom for a healthy one 3) nausea is a typical symptom of food intoxication 4) you don’t usually feel nauseated. If you want, you can show the probabilistic relevance of all these premises. Take the last one, which is known as the base rate or prior probability. if I am a healthy person and don’t usually suffer from nausea, the mushroom is most probably the culprit. If, on the other hand, I suffer from a gastro-intestinal condition and I often have bouts of nausea, my post hoc inference will be less strong.

Indeed, almost all of our everyday causal knowledge is derived from such intuitive post hoc reasoning. For instance, my laptop is behaving strangely after I accidentally dropped it on the floor; some acquaintances un-friended me after I posted that offensive cartoon on Facebook; the fire alarm goes off after I light a cigar. As Randall Munroe (the creator of the web comic xkcd) once put it: “Correlation doesn’t imply causation, but it does waggle its eyebrows suggestively and gesture furtively while mouthing ‘look over there’.” Most of the time these premises remain unspoken, but that cannot be a problem per se. Practically every form of reasoning in everyday life, and even in science, contains plenty of hidden premises and skipped steps.

So how about the post hoc arguments that we hear from quack therapists and other pseudoscientists? Someone takes a dose of oscillococcinum (a homeopathic remedy) for his flu, and he feels better the next day. If he attributes this to the pill, is he committing a fallacy? Not obviously, or at least not on formal grounds. It all depends on the plausibility of a causal link, the availability of alternative explanations, the prior probability of the effect, etc. Dismissing any such inferences as post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacies is just a knee-jerk reaction. The real problem with homeopathy is that there is no possible physical mechanism, because of the extreme nature of the dilutions, and because randomized clinical trials have never demonstrated any effect whatsoever. But appealing to post hoc reasoning by itself is not fallacious. We do it all the time when we’re taking real medicine and conclude that it “works for us”.

Professor Boudry provides several other examples in his post. He adds, “None of this is to suggest that people don’t use bad arguments. But lazy and sloppy arguments are much more common than cut-and-dried fallacies.”

The whole post is here.

Long story short: analytic philosophy still struggling to get over its early Logicist hangover. Hair Of The Dog not working, occasional doe-eyed obsession with Russell and Frege not helping either.

Yea, I agree with this completely. I stopped teaching fallacies a few years ago and just focus on getting students to put arguments in premise-conclusion form and then closely interrogating them: do we have reason for rejecting these premises, evaluating the relationship between premises and conclusion, can we think of counter-examples, etc.

He’s absolutely right. I can’t think of anything intellectually lazier than this sort of fallacy dropping.

You’re overthinking this. People often reason poorly, and there are some regularly-occurring patterns to those errors. Teaching beginning students how to recognize those patterns in others and avoid them in their own thinking is highly valuable. Do some students run off the end of the earth with it? Sure, but that doesn’t mean “don’t teach them about fallacies” – it means teach fallacies with this in mind, and help them develop some nuance about it.

This seems to me to ignore just about every substantive point made in the initial post.

His conclusion: stop teaching fallacies. My reply: no. His main point: fallacies are either not fallacious or don’t actually happen. My reply: plenty of existents between those two poles.

That is not at all his main point. The point at that point (which is not even his main point, just a subsidiary one) is that fallacies are far less common than we might think.

That’s literally his self-identified main point. It’s right at the top of his post: “Summary: Fallacy theory is popular among skeptics, but it is in serious trouble. Every fallacy in the traditional taxonomy runs into a destructive dilemma which I call the Fallacy Fork: either it hardly ever occurs in real life, or it is not actually fallacious.”

This is only half the point. The other half is that teaching fallacy theory (as he calls it) is therefore not as efficient at achieving ends of real-life argumentative competence as philosophers tend to think.

Also, and to be sure we’re on the same page in this respect at least: ‘hardly ever’ =/= ‘never’.

In professional philosophy articles, yes. In everyday life, journalism, etc., fallacies abound.

‘More common than we think’ is too vague to build a proper fight upon. Who exactly is this ‘we,’ and how common do we consider this sort of vice? Quite possibly, you and I simply disagree about how common we consider fallacies, such that I but not you think we need to start thinking they’re less common.

But it’s important not to let the debate fizzle out here. Philosophers put themselves at risk of being deaf to important perspectives if we arrogantly think of ourselves as expert in real-life argument due to our expertise in that very artificial realm of philosophical argument. We should be exceptionally careful in our own hearts of sanguinely writing off non-philosophers as less capable of constructing a logical argument.

I presume that it doesn’t need spelling out how this connects up to gender and race. Think everything from trivial mansplaining to colonial powers’ self-certainty in their ‘civilising effect’ on the ‘natives’.

Well I don’t think philosophers are particularly good at making and analyzing arguments that aren’t philosophical. Indeed, it seems to me that most dump their philosophical training as soon as they come to everyday subjects (politics being the obvious one) and end up having confidence in their beliefs that far outstrip their evidence; of course, that’s the norm across humans, but you would think philosophers would know better.

That being said, I don’t see reasons not to call fallacies as we see them. If the interlocutor is indeed a good thinker, then they can either point out how it’s not a fallacy or emend their argument (or, more likely, just block you on Twitter).

The ability to make and analyze complex arguments does seem largely restricted to the domain in which you work, which is why I find a lot of “philosophers should teach those in every other field how to REALLY think critically” arguments I see on philosophy blogs unconvincing.

I said you’ve ignored just about every *substantive* point in the essay. And you have.

Oh, and simply repeating “yes I did” is not an answer, though it may be a reply.

You mean, it’s a fallacy?

what substantial (“substantive”) points are you referring to? what was ignored? I’ll have to reread this all, but I maybe I have the wrong idea — this is a topic based on critical thinking, Kaufman, is it not?

JCM has indicated some of it.

I’m inclined to the view that many such fallacies should be viewed as (bad) inferences to the best explanation. There are times when one should infer causation from correlation – when a causal connection is the best explanation for the correlation. The same goes for ad populum and ad ignorantium. Sometimes the best explanation for why there is no evidence that p is that it is false that p. That’s why I believe there’s no tiger under my chair.

The trick, then, is to identify the good vs. bad explanations – which is a problem, but it applies to IBE reasoning generally, and isn’t unique to distinguishing fallacies.

I had taken the point of the “post hoc ergo propter hoc” fallacy to state, not that it is *never* permissible to infer from the fact that B followed A that A caused B, but rather that *their temporal order in itself* is not enough to justify the conclusion that A caused B.

Surely this is correct. In fact, as the excerpt above states, the relevant factor is context, the details, and the assumptions that go into our assessment of the putative causal relationship. But that’s exactly my point, and what I took the point of the fallacy to be: it’s not enough to just point to temporal ordering to establish causation, but rather we need to know more.

I’m tempted to say this about a lot of the “informal fallacies”. Ad populum, for instance. Sometimes the fact that many many people believe p is a good reason to think that p is true. But sometimes it’s a very bad reason to think p is true. The point is, *that many people believe it* is NOT good enough to establish the truth of p. Rather, we need to know why the believe it, what its relationship is to other known facts, etc.

And you have just explained why it is important to teach fallacies and explain how to apply them 🙂

But then, who on earth would ever claim that the fact that many people believe something is sufficient reason to believe this? I don’t think I ever encountered this argument in the wild.

We encounter it every time we hear someone begin with “we as a society have decided that x.” We encounter is every time we hear popularity conflated with quality.

Well… Neither of the examples you give seem to be statements about belief (or truth) at all, and I’m having a hard time reconstructing them in a way that they would rest upon an appeal an ad populum fallacy. The first one refers to a decision process and seems completely legit in at least some circumstances. In interpreting the second one it all depends on what you mean by ‘quality’. If we are talking about aesthetic quality, for example, we would first need to have a discussion about the notion of aesthetic truth and how it relates to aesthetic perception, before we can dismiss remarks on the evidentiary strength of popular opinion as fallacious. If you mean the quality of, say, household equipment, I would be tempted to say that prolonged widespread use is indeed an indication of an object being fit for a specific purpose, but that argument does not rely on any assumptions of what people believe.

I’m surprised. I’ve heard it often.

Could you give me an example?

Absolutely right. So long as philosophers are still obsessed with fallacy-spotting, the discipline will not rise to its potential of being relevant to real life, and the idea of ‘public philosophy’ will remain an ineffectual curiosity of interest only to privileged teenagers. I’m sick to my back teeth of psychological children smugly playing Fallacy Bingo while watching politics, as if political actors aren’t using every psychological trick in the book to suggest to their audience the often various ways in which their complex but concise enthymemes should be completed.

That’s the second person to use the word “obsess” – that’s a straw man. I’m not aware of any philosophers who are obsessed with fallacies. Fallacies are typically one chapter in intro to logic texts and occupy maybe a week and half on most syllabi I’ve seen. Hardly seems like an obsession. You also make the claim that spotting informal fallacies is what prevents is from being “relevant” – a particularly odd suggestion, since it’s precisely informal stuff like fallacies that one encounters on the op-ed page, not syllogisms in standard form. Training students to recognize the various common patters of poor inference is one of the most relevant things we can do.

Lololol this is literally exactly the sort of thing I’m lamenting.

Informal logical fallacies are also pretty rare. Almost everything everyone says builds on a rich context of shared understandings: historical references and allusions, givens, even definitions, etc., etc. Informal logical fallacies are very often ‘de-fallacised’ by taking seriously this background.

Informal logical fallacies abound. To take the most obvious example, ad hominem is everywhere. How many internet forums are not plagues by it?

Ad hominem is not everywhere, you jerk.

The ad hominem is actually an interesting example. Although it is clearly a fallacy and difficult to contextualize into something reasonable like pretty much all the others, it also – equally clearly – serves a rhetorical purpose and is very common in its undiluted form. My guess is that ad hominems are mostly tools of inclusion/ exclusion, rather than argumentative tools.

You say that informal logical fallacies are pretty rare. If you stop teaching students how to recognize them, I assure you they will soon become more common.

I’m not aware of any philosophers who are obsessed with fallacies.

= = =

Now *that* sounds like a fallacious form of argument.

Pauline Kael didn’t know anyone who’d voted for Nixon.

Oh, and by the way, I do know such philosophers. Do I win something?

I wasn’t Pauline Kaeling – in pretty much all intro to logic textbooks, it’s one chapter. How is that obsessing?

There’s not much more relevant to real life than basic reasoning skills. I teach fallacies every semester, and every semester, students comment on how useful the course is to real life. I also do a lot of public philospohy and I can think of little more useful than could result from that than a better understanding of fallacies.

I can think of little more useful than could result from that than a better understanding of fallacies

= = =

I suspect I do as much public philosophy as you do, if not more. And I can think of a lot more useful things than teaching people fallacies.

And I suspect I’ve done as much if not more than you. (I’m deliberately making a fallacious appeal to authority to be ironic –

it’s not relevant either way.) The point is, there are common patterns of bad inference; it’s highly useful to explain this to students. We see these fallacies all the time – that shows how commonplace they are. Like the various cognitive-bias problems, people will keep doing it unless it’s clarified that they are in fact problems. I see ad populam almost every day, ad ignorantium and appeal to authority almost as often.

It’s me. I have done the most public philosophy.

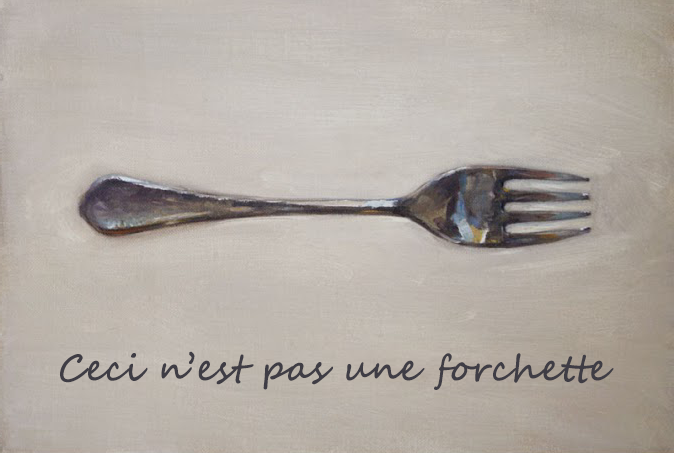

Is it writing “forchette” instead of “fourchette” a vandalization or a fallacy? 😉

A small point about the first prong. In the blog post, the author indicates this prong involves characterizing the fallacies as deductively invalid reasoning forms. But this can’t be right, can it? (Nevermind the author’s claim that these sorts of fallacies wouldn’t appear often.) For, we can express many of the fallacies as deductively valid arguments. Argument from authority:

(1) my parents said climate change is not happening.

(2) if my parents said X, then they are likely correct.

(3) therefore, climate change is likely not happening.

I suppose I thought the trick in teaching the informal fallacies was always in saying something useful and nuanced about, say, when appeals to authority are justified or not–be they inductively or deductively framed.

I’m not sure I understand this. I think treating critical thinking like a game of bingo is a real problem, especially in the skeptic scene (though I think it’s odd that, Boudry makes no connection between his students’ over-exuberance in identifying instances of fallacious reasoning and the fact that he specifically told his students to go out and find instances of fallacious reasoning). But in almost every 100-level philosophy course I’ve take (at both institutions I’ve attended), there’s been at least one or two lectures on a few basics of logical argument, including a bit about formal and informal fallacies, and in every instance, the teacher has tried to inoculate students against developing a habit for fallacy bingo by emphasizing that fallacious reasoning does not falsify a conclusion, and that informal fallacies are context-dependent (e.g. whether an appeal to authority is fallacious depends on contextual factors, like whether the authority cited is in fact an authority on the question at hand, and whether an ad hominem argument is fallacious depends on whether the personal characteristics cited are actually relevant to the issue). Lessons and assignments are planned accordingly; instead of “bring me fallacies! Fallacies for the fallacy-god!”, you get assignments like “is this fallacious, if so why, how would you fix it, etc.” Doesn’t this get around most of Boudry’s objections? If so, then what’s left is the claim that hardly anyone ever commits real fallacies. But if you read philosophy (or try to do some yourself), you’ll find them all over the place, from the Euthyphro to the Cartesian circle and Hume’s problem of induction. What am I missing?

Philosophers should pay more attention to fallacies even in their own arguments. How many philosphers indulge in Ad Hominem? We need to pay much more attention to fallacies, not less.

The person who teaches critical thinking in my department, in collaboration with me, has completely redesigned the course. Gone are the standard Venn Diagrams. Gone are the fallacies which, as Dr. Boudry notes, are typically applied by students and non-professionals in a mechanical, “Gotcha!” fashion that is the antithesis of good reasoning.

In the place of these tired old tropes that have put generations of critical thinking students to sleep, he has put a curriculum that teaches students how to critically interpret the different kinds of real communication that they will encounter out in the real world: political speech and propaganda; marketing and advertising; moral discourse; and more. The course involves theories of interpretation; hermeneutics; conversational implicature, speech acts, and pragmatics more generally speaking; rhetoric; and more.

The course has become one of our most popular with students and has earned a spot in the General Education curriculum, alongside our Introduction to Philosophy and Ethics and Contemporary Issues course.

This sounds excellent. Do you use a textbook? If so, which one.? I may be teaching a critical thinking course in future and the only good textbook I’ve found on the topic has gone out of print.

No textbooks. Very eclectic syllabus. Everything from Austin and Grice to Lewis Carroll.

Darn. Thanks anyway. I’ll keep looking.

Anyone else out there care to recommend something?

I recommend Larry Wright’s text, “Critical Thinking: An Introduction to Analytical Reading and Reasoning.” It’s probably not as fun as the course Daniel Kaufman describes, but it covers essentially the same topics and would tolerate supplementation. Note that “Reading” comes before “Reasoning” in the title: faithfully interpreting others, and faithfully articulating those interpretations, is emphasized as fundamental for thinking well. Paraphrasing another’s perception of things requires just the skills Daniel Kaufman mentions. I could go on and on about the virtues of this text, but one especially relevant to this post is that it gives students a memorable, wieldy apparatus for recognizing and articulating a lot of the messy, implicit contextual stuff that drives explicit workaday argumentation.

Thanks, Eric. I will give it a look.

Appreciate it. Didn’t know that one! Will definitely check it out.

The Adventures of Fallacy Man: http://existentialcomics.com/comic/9

PS. My own opinion is that fallacies are fun to think about it. I think that along with teaching fallacies (in the nuanced way suggested above), we should teach students to be aware of cognitive biases.

I spelled my own name wrong. Need more coffee . . .

You need more coffee at 8:03pm?

Been out clubbing or something?

It’s 10am here in Australia. 😉

Ugh and that first comment should say “fun to think about” not “fun to think about it”. Kids, this is what insufficient caffeine looks like. Don’t try it at home.

A proper teaching of fallacies does not present them in the fallacious manner alleged. Moreover, it’s a fallacy to suppose that fallacies must be in deductive form, but it’s also irrelevant. Any non-deductive argument can readily be made deductive. The fallacy in fallacious arguments stems from unsoundness.

Having just taught (likely) my last logic course over a long career of teaching at a M*A*S*H unit public university, I have to agree with most of the sentiments of the OP. I did teach the classic fallacies early in my career, egged on in part by feedback from former students. (Memory burned in brain: happened to run into a former student-turned-lawyer at a prestigious East Coast firm who remarked “Guess what book sits on my desk all the time? The logic text with all the fallacies!” Then guess what? I ironically converse-accident her remark into pedagogy for all my students for years to come, neglecting the specific role such citations might have in the courtroom that might not be so relevant in most other life.) Most of my career I became saner–there are arguments and there are wanna-be arguments. Classifying the latter into fallacies is laughable–there are potentially infinite ways to construct wanna-be arguments. Ok, some familiar patterns of “fallacy” recognition might be useful, especially given their deliberate use by advertisers and political parties to extract dollars from your pockets or game you to vote for silly idiots, but it’s better to show students that they should develop a general attitude of skepticism about discourse than to drill them on specific fallacies.

But all that said, I’m surprised that from my scanning the stuff on this thread that no one has mentioned equivocations in reasoning–which I would (inductively from my experience) argue that is the single most frequent kind of error pointed out in formal philosophical critique. I mean–how many replies can you recall reading that pointed out equivocation as the basis for criticizing some argument for such-and-such a position? I can think of at least a half-dozen of my own publications that replied in such a way.

You can definitely teach fallacies in a dumb way. Example: just getting students to memorize the names of fallacies and mechanically apply them.

But I think it can be a good idea to teach the fallacies. These are just common ways in which arguments go wrong. That’s it. You can explain that to students and get them to understand why the fallacies are incorrect and how to repair them.

When I teach this, I don’t ask my students to just regurgitate the name of fallacies on a test. I don’t even ask them to give me the names of these fallacies. I instead give them a list of arguments and ask them to tell me if and why these arguments go wrong. It is unclear to me that it is a problem to teach fallacies in this way.

I, in fact, continue to teach the fallacies in a fairly traditional way in my (very popular) critical thinking courses. But, in answer to the title question of the post, no I don’t care very much about fallacies. I teach them in the traditional way because I want students to be able to identify rhetorical manoeuvres they might find themselves flummoxed by. But I emphasize that identifying a putative fallacy is not the end of the discussion but the beginning of one in which they can determine whether what was said was genuinely fallacious in context at hand. And isn’t this what everyone who teaches the fallacies does?

The title seems slightly misleading. From what I can tell it isn’t philosophers who care too much about fallacies — I certainly don’t know many (any?) who engage in the sort of paranoid fallacy-dropping behavior described — but rather the layfolk who learn about them. These layfolk aren’t only those who have taken a critical thinking course — you’ll find them all over the internet. But I do think if you’re teaching critical thinking in a way that seems to foster this sort of fallacy paranoia then you should rethink your course design.

I also wonder if this is something like “Med Student’s Disease” where early medical students develop irrational fears that they have the diseases they’re learning about. As they gain more experience and knowledge this irrational fear tends to dissipate. With students who develop “Critical Thinker’s Disease”(?), the problem is that very few continue their education enough to lose the fear that fallacies are everywhere (and that this is a cause for distress).

I came to a conclusion that I suppose is roughly in the same vicinity about ten years ago, after several years of teaching CT. My own conclusion was/is that, in most cases, we end up dealing with a kind of matter of degree, and many alleged examples in most CT texts aren’t *undeniably* fallacious. We often end up talking about examples that lie somewhere on a possible spectrum of cases. At one end are extremely artificial, but obviously fallacious cases, on the other end lie cases that kinda sorta resemble them, but aren’t actually instances of the relevant fallacy. Typically, in the middle, are cases in which we can’t tell what the speaker/writer is trying to say (and sometimes there’s no fact of the matter). In fact, often the only way to get undeniably fallacious cases is to artificially produce examples that are so obviously nuts that it seems no one would ever actually say something like that.

For example, an old edition of Moore and Parker had an example (dunno whether it’s still in there) in which people are trying to decide where to buy ice cream, and one person suggests getting it from shop x instead of shop y because the owner of shop x needs the business. This is represented as an instance of *ad misericordiam.* Which, so far as I can tell, it isn’t. There’s just nothing defective about the suggestion. Unless being nice is a defect. A clear *ad misericordiam* would, it seems, be along the lines of: the ice cream at shop x is better because the owner needs the business. But who would think or say something like *that*?

I still think it’s good to think about certain fallacies. But I talk to my students about this problem, then give them exercises in which they consider a range of cases from (e.g.) unequivocally illegitimate appeals to tradition, through unclear cases, to perfectly fine arguments that only superficially resemble appeals to tradition. They have to demonstrate an understanding of the general idea of a range of cases, and learn to arrange cases from clear-cut-but-silly, through god-knows-what-this-person-is-saying to only-superficially-resembles-the-fallacy.

Overlaying all this, I tell ’em that learning about fallacies is just a way to help understand and evaluate reasoning and related phenomena. It’s important that they realize that, fascinating as the question “Is this *teeeeechnically* an instance of the *tu quoque* fallacy?” might be, it often just gets in the way. I tell them that I think they should focus on that question until they can make a judgment about how strong/weak the argument is, then make the judgment and move on.

This all works pretty well, IMO.

(Incidentally, I’m inclined to think that there are applications of this in philosophy, but this is too long already.)