Should Journals Publicly Grade Submissions?

Jonathan Weisberg, associate professor of philosophy at the University of Toronto and managing editor of Ergo, notes that by the time a paper is published in one journal, it has likely made the rounds at a few others, and hence has been reviewed by several people whose opinions on it are not publicly available. These people have already “thought about [the paper’s] strengths and weaknesses, and they’ve generated valuable insights and assessments that could save others time and trouble. Yet only the handling editors and the authors get the direct benefit of that labour.”

He adds:

The current system even encourages authors to waste editors’ and referees’ time. Unless they’re in a rush, authors can start at the top of the journal-prestige hierarchy and work their way down. You don’t even have to perfect your paper before starting this incredibly inefficient process. With so many journals to try, you’ll basically get unlimited kicks at the can. So you might as well let the referees do your homework for you.

It’s an inefficient process that has led to an arrangement that “is sagging low under the weight of premature, mediocre, even low-quality submissions.”

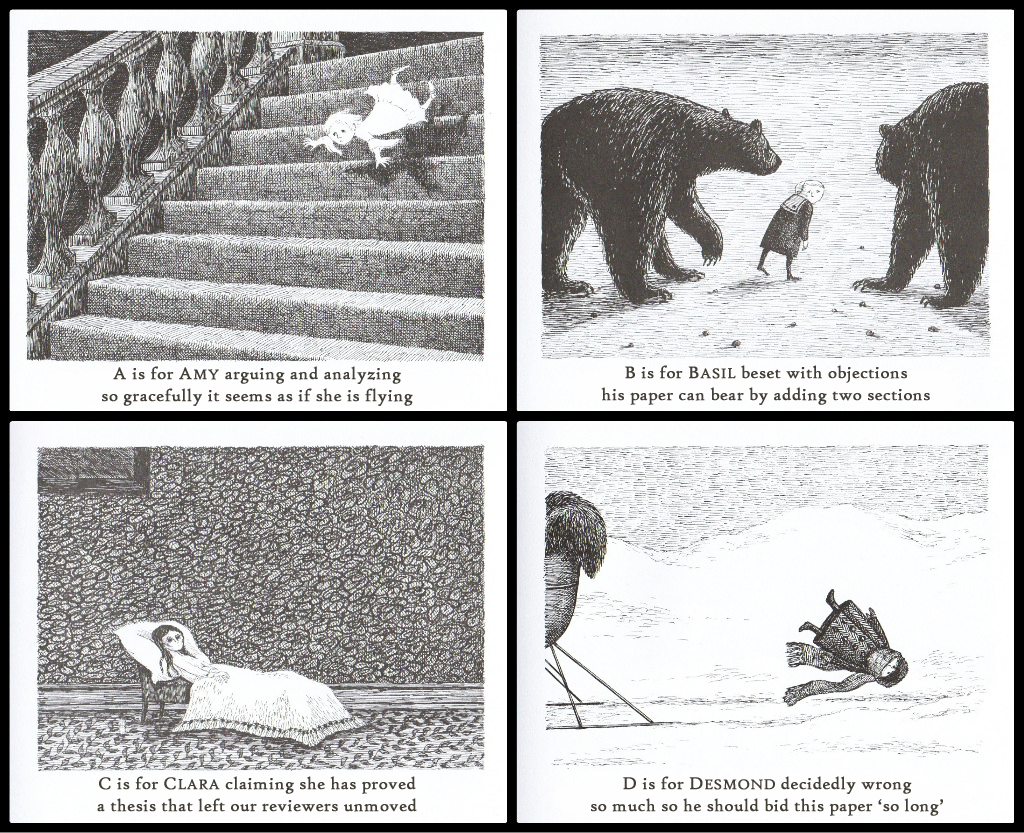

What can be done? Weisberg entertains the following idea: journals should publicly assign grades to submissions—letter grades, like A, B-, D+, etc.

Here are some advantages to the proposal:

- Authors might be more realistic in deciding where to submit. They might also wait until their paper is truly ready for public consumption before imposing on editors and referees.

- Readers would also benefit from seeing a paper’s transcript. Not only could it inform their decision about whether to read the paper, it could aid their sense of how its contribution is received by peers and experts.

- Editors could even limit submissions based on their grade-history, e.g. “no submissions already graded by two other journals”, or “no submissions with an average grade less than a B”. (Ideally, different journals would have different policies here, to allow some variety.)

He considers some downsides of the proposal, too, noting that those who are disadvantaged by a lack well-developed professional networks for sharing and receiving feedback on their work prior to sending it out for review may end up with papers that have worse grade transcripts, compounding their disadvantage. Overall, he is not sure what grade to give this proposal, but, he says, “we can’t keep going as we have been.”

You can read more about the idea here.

Suggestions, modifications, criticisms, alternatives welcome.

An interesting idea! Thanks to Jonathan for taking the time to formulate it and to Justin for featuring it.

I’m all for rethinking current practices, but I tend to not favor solutions that further empower anonymous referees. Currently, the fact that a journal rejected a paper contains almost no informational value. In that spirit, I noticed what appear to be a few typos or omissions:

“[prior reviewers have] generated valuable insights and assessments that could save others time and trouble” –> “prior reviewers have generated some valuable comments among many confused, worthless or positively harmful ones that would cause others time and trouble.”

“The current system even encourages authors to waste editors’ and referees’ time.” –> “In addition to encouraging unaccountable anonymous referees to waste authors’ time, the current system also encourages them to waste editors’ and subsequent referees’ time.”

“So you might as well let the referees do your homework for you.” –> “However bad you think philosophers are at producing worthwhile research papers, in the role of anonymous referee they tend to be even worse at helping other philosophers produce worthwhile research papers, so don’t be tempted to let the referees do your homework for you.”

🙂

Seriously, perhaps a simpler and more immediate way to reduce the overall strain on the system would be for philosophy editors to be more proactive in critically evaluating referee reports. If authors felt that, in general, the system guarded against false negatives (i.e. rejecting a paper based on erroneous negative evaluation) nearly as much as it guards against false positives (i.e. publishing a paper based on erroneous positive evaluation), then authors might not take such a cynical and unsustainable approach to submission. This could increase the perceived informational value of rejections and the reports they are based on.

I agree with John Turri. As Jason Stanley shared not too long ago,

“My 2002 paper “Modality and What is Said” was finished in 1996 and rejected from 11 journals. And yesterday’s desk rejection without comments was the fifth desk rejection without comments I have received since 2011….Four of my papers that were rejected from multiple top journals subsequently became among the 20 most cited papers in those very journals since 2000.” (http://philosopherscocoon.typepad.com/blog/2015/09/stanley-on-peer-review.html)

I worry that this sort of thing is not at all uncommon, and that if journals adopted Weisberg’s proposal, potentially influential papers like Stanley’s might never be published at all or be “placed out” of high-level/prestigious venues due to the “bad word of mouth” generated by public referee “grades.”

I also suspect (as Weisberg’s remarks recognize to some extent) that early-career scholars without large professional networks are the most likely to suffer these sorts of negative consequences if the proposal were implemented–and that early-career people are those that we should *least* want to jeopardize in the publication process. It is easy to ensure that a paper has few dumb mistakes if you can present your paper at colloquia, invite-only conferences, etc.–as people at well-placed research institutions can readily do. It can much more difficult for people at smaller, non-research institutions to get anything like the same amount of feedback prior to submission.

I agree with the above comments regarding early-career people. I do my best to make sure papers don’t come to journals with obvious mistakes, gaps, etc. But as someone in a fairly small department on a temporary, undergrad teaching-only contract, with no funding for conference attendance, my opportunities for informal and semi-formal peer review are limited. Some of the most helpful reviews I’ve received have been absolutely scathing, pointing out serious errors and gaps in a paper I really thought was a good piece of work. In some instance, I’ve then managed to turn things around so that I actually produce a good piece of work that’s then well received.

What’s more, as Weisberg notes, this has broader repercussions. Of course early-career folk want to publish for its own sake. But we are also under pressure to publish precisely to try to get out of the precarious positions we are often in. A system than punishes people – albeit unintentionally – for not already being somewhat successful is surely not the way forward.

“With so many journals to try, you’ll basically get unlimited kicks at the can.” Except that each review takes time, and after several rejections a paper may not be a response to the state of the field any more. Even though there’s this common claim that you can publish anything by sending it to enough places, I think all of us have papers which we ultimately gave up on because their time had passed (grating that some of these were bad papers and it is good that they were never published).

“Readers would also benefit from seeing a paper’s transcript.” Wikipedia similarly records a kind of slime-trail history of every entry, but almost nobody looks at it. Unless the history of a document especially matters to me for some reason, I consult either the canonical version or the most readily available version. I don’t want to have to look at multiple drafts and comments back and forth about revisions for everything I read.

Journals should be doing more to circumvent implicit bias in the refereeing process, not introduce new ways implicit bias can take hold. If there is a public “report card” it will undoubtedly bias the referee’s reading of the paper. This would not necessarily be a problem if we had reason to believe an anonymous referee is grading on some objective shared measure, but we do not have reason to think there is such a measure. Referee’s disagree on the same paper. I once had a paper at a top journal where one referee thought it should be accepted, one thought it should be revised, and a third thought it should be rejected. I do not think my experience is unique.

It also strikes me that such a policy will further discourage women and others from underrepresented groups in philosophy from sending papers to top journals. No one wants a bad grade that a hiring committee or tenure committee could use to make decisions. There already is a problem that there is a low percentage of female authors sending papers to top journals compared to the total percentage of women in the profession. This policy will just perpetuate an already existing problem.

If there’s a problem with referees, as the previous commentors suggest, then journals should instead record (private) grades of the referees, to avoid the repeatedly bad ones. I would have thought that journals do this already, although perhaps I am mistaken.

(For what it’s worth, my experience is that referee reports are more often helpful than not, if only in flagging which part of my papers require further elaboration/clarification.)

As for grading submissions, I am not very much in favor, although I can certainly understand what’s motivating the proposal. It is possible for a paper to improve very dramatically from one submission to the next, and a grade for a previous draft could be quite misleading.

My own feeling is that desk rejection ought to be used more. As a referee, I find that submissions often contain problems worse than those in my grad students’ term papers. (To be sure, they often contain insights that cannot be developed in the time/space allotted to a term paper.. But the frequency of fatal flaws in journal submissions is alarming.) Naturally, this alternate proposal creates more of a burden for editors, but I suspect recruiting more associate editors would help on that score.

Ted, the AJP assigns each referee a grade, which is a function of the timeliness and the quality of their reports.

Neil, does this end up having the side effect of having good timely referees inundated with further requests to referee, while the bad ones don’t have to do them anymore?

Barry, it is designed to steer us away from bad referees. That’s a feature, not a bug, especially since one reason for a low score is how long bad referees often take for their shoddy reports. We have the policy of not asking anyone to review more than 2 papers in a 12 month period (with the exception of cases in which they have agreed to look at a subsequent version of a paper which has been resubmitted). I try to avoid asking anyone from reviewing more than once in a 12 month period. But given that many people almost never accept review requests, the refereeing burden is very unevenly distributed at all journals, I think.

Since I only gave a criticism, Justin asked for suggestions, and Weisberg noted that, “we can’t keep going as we have been”, allow me to make a suggestion I have made elsewhere before.

Academic math and physics have a very different peer-review publishing model than ours, and from what I can tell it works far better than ours. In those disciplines it is standard for everyone to publicly upload working papers to a central repository (in physics it is the ArXiv). Once papers are uploaded, it is standard practice in the field for people to read and provide feedback. Authors then revise and upload new additions,and the ArXiv keeps a record of each submission in case there are any issues of priority or theft of ideas). The level of public discussion that results (and yes, little known authors’ papers are regularly discussed too!) typically improves paper quality greatly, indicating to authors which of their papers are likely to do well when submitted to a journal and which will likely be a waste of everyone’s time. Although this system does basically undermine “anonymoized” review–which isn’t really that anonymized anyway in the current age due to Google reviewing, paper sharing, invite-only conferences, etc.–my understanding is that mathematicians and physicists generally find it more fair and merit based than the traditional anonymized peer review process we still use. It usually comes out very quickly in public discussion whether a paper is good or bad, as people publicly debate the merits of the paper in question. In contrast, under our discipline’s traditional anonymous review process, a paper can spend 6 months at a single journal and may be evaluated incompetently, often enough with only a one or two sentence “justification” for rejection by a reviewer (I’ve been on the receiving end of a few of these).

In short, the math and physics process is more efficient, more fair, more merit-based, and improves papers prior to publication better than our system does. What’s not to like? If as Weisberg notes our process no longer works, maybe we should use an alternative process that other fields have shown to work.

I think that this is a terrible idea. Suppose I submitted a paper and it got a B- by that journal. Suppose I then subsequently rewrite the paper and now want to submit it to a different journal. Is this the same paper that got a B-? What determines whether it is? How, on this proposal, will journals determine whether it is the same paper? Thus, how will they determine whether this is a different paper that’s eligible for submission or the same paper with an average grade lower than a B and thus ineligible for submission.

If I’ve substantially rewritten the paper and have adequately addressed the concerns that resulted in my initial submission’s getting a B-, how is this going to inform (as opposed to misinform) the public about whether it’s worth reading. How’s a transcript of what reviewers thought of the initial submission and its strength and weaknesses going to help in assessing the rewritten (new?) paper that I now want to submit, which will have different strengths and weaknesses. What if the reviewers were wrong or incompetent? Just as people can submit bad papers, reviewers can submit bad reviews.

Also, I don’t share Weisberg’s dismal assessment of the current state of things. I don’t think that very many people are hoping to have referees do their homework for them. And I think that, as an editor, I can fairly easily and quickly desk reject (and without comments) papers that have very little chance of passing review. If anything it seems to me that this system would make things less efficient. The editor couldn’t just simply desk reject a submission without comments. He or she would need to give the paper a PUBLIC grade. And the editor couldn’t do this quickly, for the stakes would be extremely high. A very low grade would be a public insult that would pretty much blacklist the paper. I would not want to do something like that without justifying myself publicly. And if I had to publicly justify myself every time I would otherwise desk reject a paper without comments, that would take a tremendous amount of time. I would be more likely to pass on the paper to reviewers, so that they would bear the burden.

Lastly, I agree with what others have said above. Some great papers have received several rejections before being published. This proposal seems to give way too much power to the first few reviewers. They can pretty much determine whether the paper will have a future.

Amen!!

The difference between revising a paper and scrapping it and writing a new paper on the same topic is largely a matter of an author’s stipulation. If this proposal were implemented, papers with bad grades would be abandoned and replaced with fresh papers that are remarkably similar.

“The current system even encourages authors to waste editors’ and referees’ time. Unless they’re in a rush”

Given the enormous pressure to publish, who isn’t in a rush these days?

And the editors’ time and ref’s’ time are more important than the authors’ time to write, submit, fill out the endless forms…etc…??? This smacks of the elitism of journals, such that our refs and editors are so important that we cannot waste their time. This is such a long standing elitism in the APA and elsewhere (and I go back to the 70’s on this issue) that it ought to be excised.

These alternate reality discussions are always interesting because of what they leave out. Go back and read some of the earlier threads here with editor participation (particularly Velleman’s comments, as I remember) and you’ll see the problem. The stated virtue of journals is that they provide a publishing venue for work that meets a certain standard. That standard, rough as it is, is a necessary condition, not a sufficient one.

The reason given for the high percentage of desk rejections is that there are just too many papers to send out for review. In what world can a few editors properly review all those papers? The conceit is that most of them have obvious flaws that are easily identified. But papers with high citation rates are frequently desk rejected. Everyone knows this.

The great virtue of this proposal is that it would force editors to take a public position on papers submitted to them. The reason why it will never happen is not because that position may not be the best thing for authors, but because those positions will often, in retrospect, look rather foolish. The present-day system is in large part built on top of the opacity and anonymity of the desk rejection.

Desk rejections may be opaque, but they aren’t anonymous, at least not generally. When I desk reject papers at Utilitas, my name is at the bottom of the email. And I think that Doug Portmore has already explained why editors wouldn’t necessarily look foolish for assigning low grades to papers that end up becoming influential: because it will never be clear whether the version of the paper that they graded poorly is the same version that was published eventually elsewhere. The proposal is a non-starter, for (at least) the reasons Doug gives, but not because editors are too protective of their reputations. I’m under no illusions about my own infallibility:

I’m sure that some papers I will desk reject will eventually be published in other journals. Occasionally, one might even become well cited. Anyone who would think less of an editor for occasionally making that sort of error has never been an editor.

No, the only possible reason to do so is to embarrass the authors. The idea that authors are wasting the time of referees and editors is self-serving garbage. If you don’t want to read anything but a submission by Russell or Kierkegaard, don’t become an editor. This reminds of the “old boy network” wherein only those we already deem important get consideration. Again, if you don’t want to receive articles you think are inferior, don’t sign up as an editor or referee. You are not so important that your time is that valuable. Think about this: Would you want to say your time is wasted by teaching all levels of students and you should only have the best?? If so, get out of education and teaching. This elitism of referees and editors (for themselves) has gone on too long.

The point of teaching is to help the student. The point of refereeing is to secure the standards of scholarship. The poor student needs the help of their teacher; the poor paper needs to be rejected. My responsibility as teacher is to the student; my responsibility as referee is to the editors and the wider scholarly community.

TL;DR: The tasks aren’t comparable.

Note that I did not say referees and teachers were the same. But do we publically humiliate students by publishing their grades nowadays? I am old enough to have seen grade point averages, test results, standings in a class posted in the hallway on a public bulletin board. Was standard operating practice. The, in about the 70’s this was dropped for the now obvious reasons — should it not also apply to authors?? This is private information and why should the general audience know that prof X submitted an articled to journal Y and they trashed it???

One suggestion I have is for experienced faculty to stop encouraging graduate students and junior faculty to use the referee process as a way of obtaining comments on a paper.

I received that advice numerous times from a number of people, including very well-established senior faculty members (“Just send it out! Get some comments!”) I always rejected that advice, instead working on my paper until I thought it was truly ready to be considered by a good journal. Perhaps in consequence of that, I have most often received ‘revise and resubmit’ or ‘conditional acceptance’, and very few outright rejections. That confirmed my thought that I had been right to reject the advice, “Just send it out!”, which seems inefficient and a waste of everyone’s time.

I also recall one colleague lamenting that a paper that had made the rounds seemed destined never to be accepted, because it had turned into something that just responded to previous referees’ suggestions and criticisms. That too made me think that my own approach was ultimately more efficient; many papers have problems too deep for referees to have time to address, so they cite more easily explicable problems as their reasons-to-reject, and authors who concentrate on fixing those problems are often investing time on the superficial rather than the fundamental problems.

While I understand the worry, there is something about getting comments back from anonymous reviewers that can’t really be duplicated in self-review or even having well-informed colleagues read a paper (if you are lucky enough to have such colleagues or such a network). When starting out, I worked very hard on a paper, and sent it out, and got lots of comments back from a series of revise and resubmits. I had to sift through those comments, determine which were valuable, which were central. In some ways I trusted the reviewers too much, in some ways I avoided dealing with overarching issues in the paper, regarding clarity and simplicity. But that process taught me to be a better writer, to write with a journal audience in mind, to make absolutely clear the impact and purpose of the paper, how to respond to “superficial” comments in a way that deals with objections adequately and yet doesn’t detract from the main argument of the paper, etc. These skills I learned through the review process, and while that’s not the main purpose of the review process, I don’t think it’s right to see it as a kind of abuse of the review process, or “wasting people’s time”

I’d be interested in hearing more about your publishing experience, uggioso. Prima facie, and assuming that you have submitted a sufficiently high number of papers for your experience to be meaningful, and assuming you are submitting to top 20 philosophy journals, the most likely explanation for why you have received few outright rejections is that you have been exceptionally lucky. As Marcus Arvan mentioned above, even Jason Stanley is rejected regularly. I don’t think that’s because he’s not polishing his papers sufficiently.

Indeed, and immediately after posting, I regretted having implied that any generalizations would be possible, but it wasn’t possible for me to go back to edit my remarks. I also don’t deny that using the process as a means of obtaining comments can benefit authors. Still, using the process as a means of obtaining comments seems to me to demand too much of referees.

I’ve not seen anyone raise this yet as a reservation so: Would referees even *want* to assign grades to submitted papers? Maybe I’m idiosyncratic in this but I absolutely would not, not even if they were never publicly posted. It skews the mind in strange ways, rendering the process of refereeing too much like student grading, a work undertaken not with peers, but with subordinates. Grading and refereeing require utterly different mindsets for me. I try very hard to conceive authors whose work I referee as *colleagues* not subordinates, and grading their work would undermine that.

While the original proposal seems to me to be indefensible, for reasons that others have given, I wonder if it might be improved by being taken further. As I understand it, the original proposal calls for journals to offer ratings of papers submitted while still being in the business of being journals and selecting papers for publication. But suppose that journals stopped being journals and became nothing more than rating agencies. Papers might be submitted to an online open-access archive, and authors could choose to submit papers to a rating agency for an evaluation. The evaluations would be made publicly available, which would be of use to readers in deciding what to read and universities in things like tenure decisions. We probably wouldn’t want the ratings to be in the form of letter grades, for the reasons that Amy gives, although I’m not sure what format would be better. (“My paper got 3.5 Platos from Ethics!”) Some system would need to be in place to prevent people from sending the same paper out to multiple rating agencies for review. Perhaps it would be enough if for evaluation purposes all ratings of all papers were considered, not just the highest or final rating of a given paper. Admittedly, reviewers would be much more likely to know the identity of the author of a paper.

For what it’s worth, I lazily floated an idea of this sort on my seldom-updated blog a while back:

Journal X forms a consortium with journals Y and Z (their audiences are similar and they broadly trust each other’s judgment). The peer review process would then work like this:

– Author A submits her ms to the XYZ consortium, without specifying a journal preference.

– The ms is assigned to one of the three journals’ editorial team by simple sequential rotation, i.e. ms 1 to X, ms 2 to Y, ms 3 to Z, ms 4 to X, etc.

– If the paper is sent out for review, once the reports are in, they are shown to the editorial teams of all three journals (a consortium could perhaps afford the luxury of using, say, three reviews instead of the two that the single journals normally use).

– Each journal makes a decision on the ms.

– Offers from R&R and upwards are passed on to A (e.g. X offers a minor revision, Y offers a major revision, Z rejects, so no offer).

– If A accepts one of the offers the process is carried further by the journal in question.

More details here:

http://enzo-rossi.tumblr.com/post/130816262210/journal-pooling-a-peer-review-pipe-dream

Nice proposal! A friend suggested an idea in this neighbourhood a few years back, which I also like. Basically, journals start splitting their content into A, B, and C series. So instead of rejecting a fine-but-not-great submission, *The Such and Such Journal of Philosophy* could offer to publish it in *The Such and Such Journal of Philosophy, Series B*. The author can then accept, or, if they think it’s really a great paper, they can try another journal in the hopes of getting in their A series.

A variant of this has been tried in the law review world. Law reviews are mostly not peer-reviewed, but they also do not require exclusive submission. Many people have wanted to move them to being peer-reviewed, but outside the fanciest law reviews, most authors weren’t willing to pay the price of exclusive submission, and it wasn’t sensible or efficient for 50 law reviews to all seek referees for submissions to which they did not have exclusive rights.

Enter the Peer Reviewed Scholarship Marketplace. Here’s the description from their website:

“PRSM, a consortium of student-edited legal journals that believe that peer review can enhance the quality of the articles that journals select and ultimately publish. PRSM works much like the familiar manuscript submission vehicle ExpressO but with a peer review component. Authors submit their work exclusively to PRSM, whose administrators then arrange for double-blind peer review of each manuscript. After six weeks, PRSM members will receive a copy of the article with the reviews… members will make their own independent offers to authors, who are free to accept or decline. If an author is unsatisfied with all offers—or receives none after a designated date—he or she is free to resubmit his or her reviewed manuscript through ExpressO or another preferred vehicle.”

I could see this idea working for at least a certain range of philosophy journals…

http://www.legalpeerreview.org/about/

Well that went over like a lead balloon! Thanks everyone for your thoughts, critical though they were.

I see I should have stressed the benefits to *authors*, since that’s the direction a lot of people are coming from. So fwiw, here’s how I came to this idea, as an author.

I’ll be the first to admit that the bulk of my work is B+ material. I’ve never written an A+ paper in my life, and Homer Simpson could count my A/A– papers on one hand (best case).

Reputable journals only publish A material though, at least that’s the conceit. So I waste a lot of my life trying to dress up B+ ideas and pass them off as A– papers. I go from journal to journal until someone is sympathetic enough, or in a good enough mood, or indifferent enough to say, “Sure, I can see this as an A–”. It’s time consuming, anxiety provoking, and, frankly, embarrassing.

I would much rather just send my B+ paper to *Phil Review*, get my B+, and have my peers interested in the topic know that there’s a B+ idea here, in case they find it helpful. To gratify my administrative overlords, I can then send the paper off to *The Southern Ontario Journal of Mediocre Philosophy* to be indexed and typeset (badly).

This system would save me, as an author, a huge amount of time and trouble. And my experience as a referee and a reader suggests that I’m not entirely atypical. We are awash in B-list material circulating from journal to journal in search of a lucky break onto the A-list.

Maybe I’m wrong about that. Maybe philosophy really is the place where the arguments are strong, the CVs are good looking, and all the journal submissions are above average.

But I suspect most of us know better. We’re just afraid of giving up the pretense that our B+ papers deserve their place on the A-list. But we should remember, our fellow B-listers will all be affected similarly. If we all agreed to just start calling a spade a spade, maybe we could spend more of our time playing cards, and less time shuffling the deck.