Traits of Deontologists and Consequentialists: Appearance and Reality

People who hold deontological moral views appear to others to be more “pro-social,” but actually aren’t, according to a new study. The study, entitled “Are Kantians Better Social Partners? People Making Deontological Judgments Are Perceived to Be More Prosocial than They Actually Are,” is by Valerio Capraro (Middlesex University, London) and seven others, and is available for download at SSRN.

The study investigates an evolutionary hypothesis for the prevalence of deontological moral views, namely that holding such views “work as a mechanism to signal social desirability.” The authors write:

this mechanism is evolutionarily favorable only if people preferring deontological courses of action are actually more socially desirable than people preferring the competing consequentialist course of action. Otherwise, potential partners would ultimately learn that deontologists are not socially more desirable than consequentialists, which would eventually lead to the loss of deontologists’ evolutionary advantage.

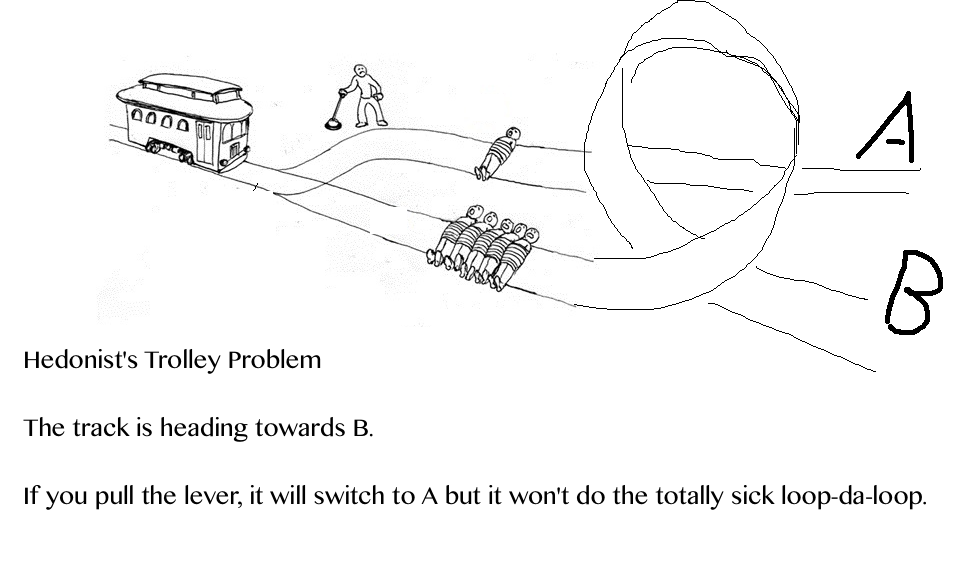

The authors’ method is to present participants with moral dilemmas (e.g., some trolley problems and other cases) in which there’s a choice “between a characteristically deontological and a characteristically consequentialist option” to see whether their behavior “can significantly predict prosocial behavior, which we see as one of the main ingredients of actual social desirability.”

They break “prosociality” into various forms—trustworthiness, altruism, and cooperation—and run studies for each. For each of these traits, they find that deontologists are perceived by others to exhibit it more than consequentialists. They also find that for each of the traits, consequentialists exhibit those traits at least as much as deontologists. They also look at a subset of deontological views characterized by “respect for others” and come to the same conclusions.

Perhaps unfashionably, I think that trolley problems and other stylized examples are quite useful in moral philosophy. However, I’m not sure how much they contribute to an evolutionary explanation of moral views.

These cases typically help themselves to omniscience, which is useful for isolating variables to focus on. That means, though, that they are rather different from the epistemic contexts in which we evolved and now live.

Additionally, the cases are designed to tease apart the implications of different moral views, whereas in the particulars of everyday life, the best versions of deontology and consequentialism at least seem to agree a lot. That would be worth taking into account in trying to figure out why, from an evolutionary perspective, certain moral views have persisted.

The full paper is here.

I am not sure why anyone would begin with the idea that deontology would be more social than consequentialism. I will read the whole paper. But it seems to me counter-intuitive since a strict deontologist, as an absolutist, would be perceived tom favor principle over people, while a consequentialist would be primarily interested in effects on people. Interesting. Sorry for posting before reading whole paper, but this is just my initial reaction.

This seems counter intuitive to me — deontologists seem committed to principle and thus can overlook social effects of following principle. Consequentialists would seem to me to be more likely to take social effects into account and discard absolute principles in favor of effects on people and society. Interesting. Will read whole article, but this is my initial reaction.

Like DocFEmeritus, I was astonished to hear than consequentialists are perceived as less social than deontologists. If anything, I would have thought they would be *more* social. I wonder if they are regarded as less social because they place no intrinsic value on personal loyalties. Or, perhaps more likely, they are regarded as less social because their moral system is unusual, and so they can come across as amoral. People with different moral systems can seem somewhat alien and monstrous.

I just want to point out that the connection between what the authors call “characteristically deontological/consequentialist” judgments and the moral theories with those names is extremely tenuous. This has been pointed out repeatedly by Guy Kahane, and is just as often ignored by authors working on this topic. Put simply, in the trolley case, W.D. Ross could easily have told us to flip the switch, and J.S. Mill might have said you should leave it alone. This is basic moral theory: the former could cite a prima facie duty to help as many people as you can, and the latter could have deployed indirect-utilitarian reasoning to argue that people in general shouldn’t take it upon themselves to kill because they think it will save lives.

This line of research badly needs a new name for what it is studying. It is not studying the comparative evolutionary fitness of “deontologists” or “consequentialists”. Rather, it is studying people who signal, on a piece of paper or a computer screen, that they have certain priorities, preferences or values. You decide how much that tells us about the actual evolution of morality.

Hi Joe, first of all thanks a lot for the very useful comment. I would like to point out that in our paper we have been very careful in the terminology. For example, we say “people making deontological choices in moral dilemma X”, rather than “deontological people”, because we are perfectly aware of the “tenuous” connection that you rightly pointed out.

A part from that, I think that the main point of the paper is that there is a perception gap: people who make deontological choices in what-we-call “the trapdoor dilemma” are perceived to be more trustworthy and more altruistic than they actually are. Of course, if you change dilemma, other things can come out (for example, we show also that the same gap is *no longer* there when you replace the trapdoor dilemma with the standard trolley problem). Where does this gap originate from and why is it that dilemma-dependent is an open question which is not easy to answer, at least for us.

Why is everything a face-off?

To elaborate, I’m skeptical of the attempt to determine which moral theory of the two ought to be crowned the most socially desirable given that I don’t imagine many people are actually hardline deontologists or consequentialists in practice.

This study, like much else in moral psychology, is basically a proximate-level footnote to Richard D. Alexander’s 1987 BIOLOGY OF MORAL SYSTEMS, where you’ll find its full ultimate-level explanation (e.g. p. 120).