The Anti-Authoritarian Academic Code of Conduct (updated)

People are wondering how authoritarian the United States government will become under a Trump administration. There’s no way to know for sure. Perhaps the answer is: no more than it already is. Or perhaps Trump, who seems to be some combination of much less knowledgeable of and much less respectful of the limits of executive power than any previous U.S. president (even in this era of the “imperial presidency”), will attempt to pursue his illiberal aims via a wide array of means, including issuing directives to or putting pressure on the institutions and individuals of academia.

Under conditions of uncertainty, how do we identify the line between panicked overreaction and responsible preparation?

That’s a tough question, in part because preparation and precaution are almost never without costs or tradeoffs.

At the very least, we could look for and assess minimally costly means of preparation. One option along these lines is to try to mentally prepare ourselves to refuse to cooperate with illiberal or immoral government initiatives.

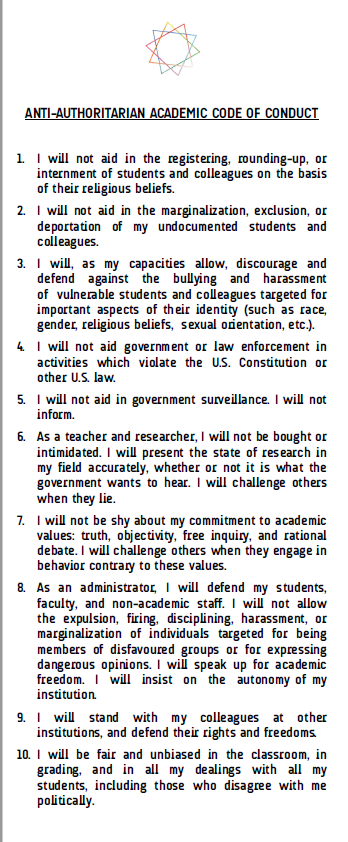

To that end, Rachel Barney, professor of philosophy and classics at the University of Toronto, has drafted an Anti-authoritarian Academic Code of Conduct—“to keep the bright lines visible” she says—which she wishes to share with philosophers and others in academia. I post it below, with some slight edits. Feel free to make suggestions for revisions in the comments, keeping in mind the purpose and limits of such a document.

- I will not aid in the registering, rounding-up, or internment of students and colleagues on the basis of their religious beliefs.

- I will not aid in the marginalization, exclusion, or deportation of my undocumented students and colleagues.

- I will, as my capacities allow, discourage and defend against the bullying and harassment of vulnerable students and colleagues targeted for important aspects of their identity (such as race, gender, religious beliefs, sexual orientation, etc.).

- I will not aid government or law enforcement in activities which violate the U.S. Constitution or other U.S. law.

- I will not aid in government surveillance. I will not inform.

- As a teacher and researcher, I will not be bought or intimidated. I will present the state of research in my field accurately, whether or not it is what the government wants to hear. I will challenge others when they lie.

- I will not be shy about my commitment to academic values: truth, objectivity, free inquiry, and rational debate. I will challenge others when they engage in behavior contrary to these values.

- As an administrator, I will defend my students, faculty, and non-academic staff. I will not allow the expulsion, firing, disciplining, harassment, or marginalization of individuals targeted for being members of disfavoured groups or for expressing dangerous opinions. I will speak up for academic freedom. I will insist on the autonomy of my institution.

- I will stand with my colleagues at other institutions, and defend their rights and freedoms.

- I will be fair and unbiased in the classroom, in grading, and in all my dealings with all my students, including those who disagree with me politically.

If you agree with enough of this, please share it with others at your school and in your social networks. Consider printing it out and hanging it in your office or on your office door.

And keep these ten items in mind, so if the time comes, you are a little more prepared than you otherwise might be.

Click on the image below for a PDF version:

(Note: no need to turn the comments section here into a list of people who plan to adopt this code of conduct.)

UPDATE (11/30/16): Inside Higher Ed covers the anti-authoritarian academic code of conduct.

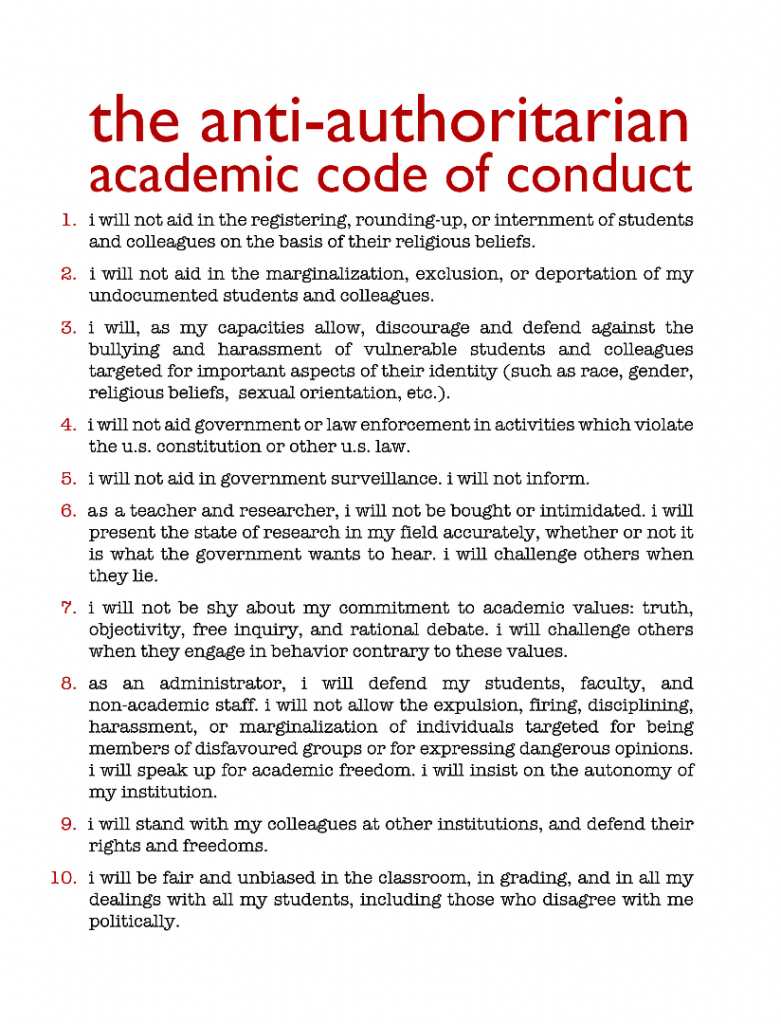

UPDATE (12/8/16): A philosopher has made a larger version of the poster. You can have an 18 x 24 inch version printed at a copy shop. Click on the image below to download it.

Regarding 8: I’m not sure what a ‘dangerous opinion’ is. Is this an opinion which is regarded as dangerous by the government or by the academic concerned? I note that 3 does not include political beliefs or opinions in the list of ‘important aspects’ of vulnerable students’ and colleagues’ identities.

I wonder if this is intentional and, if it is, whether or not the right to express political beliefs, and to be free from persecution on the basis of such beliefs should not be included in the list?

Would this be in tension with academic responsibility to challenge beliefs, at least, in the political philosophy classroom? And are, say, racist beliefs to be regarded as political beliefs, or dangerous opinions? If they are, should students disciplined for expressing such beliefs? Or would they deserve equal protection?

These questions are all meant genuinely, I have no particular answers in mind.

takaashigani, I can’t speak for Rachel Barney, who drafted the list, but in response:

on 8: I don’t know exactly what makes an opinion “dangerous.” It could mean both of the options you countenance and others (e.g., opinions that it are dangerous for the person to express for some reason or another). What 8 directs academics in their capacities as administrators (probably should have added as teachers, too) to do is to protest, or not cooperate with, or not allow punishment for the expression of a wide range of opinions. This is compatible with criticizing opinions, arguing about them, and lots of other speech acts in regards to them. There’s a huge difference between challenging and criticizing opinions and “persecuting” people for them. It’s also compatible with paying attention to the composite action of which the expression of opinion is a part (e.g., is it part of a speech inciting imminent violence?) and responding appropriately to that composite action. In any list like this, there will be some vagueness and room for the operation of individual judgment.

on 3: political beliefs and opinions are not included in 3 and I did not add them because (a) I don’t think the way they contribute to a person’s vulnerability (when they do) is usually comparable to the ways in which race, gender, and sexual orientation contribute to a person’s vulnerability and (b) political opinion is discussed in 8 and 10. (Of course, things could have been arranged differently.)

I agree with takaashigani re. dangerous opinions. If by “dangerous opinions” you mean opinions that are believed to be dangerous by an authoritarian regime — or that are in fact dangerous to that regime — then the expression of such opinions should be protected. By if you mean opinions — such as hate speech — whose expression poses a genuine danger to other people — or at least those who don’t deserve to be endangered — then I’m not so sure (although in some moods I am inclined to think any speech that falls short of inciting violence should be protected).

“By if you mean opinions — such as hate speech — whose expression poses a genuine danger to other people — or at least those who don’t deserve to be endangered — then I’m not so sure”

Are you serious that we should make policy here by dividing possible victims of speech into those who do and do not deserve to be endangered?

I seem to have a bad habit of including parenthetical remarks — even in blog comments — designed to stave off hypothetical, and sometimes unlikely, objections to the things I say. The remark in question was simply meant to be a concession to someone who might be inclined to think speech dangerous to an authoritarian regime itself is morally permissible. So, no, I don’t think that a policy on speech which distinguished between those who do and do not deserve to be endangered is justifiable in a liberal democracy. But I at least open to the possibility that some such distinction might be morally significant in a different political context.

Okay, that’s fair enough.

This mostly looks laudable. Specifically, 3-4 and 6-10 look fine. (I was reading “dangerous opinions” in 8 broadly, to include any opinion short of direct incitement to violence, not just the ones the government doesn’t like.)

1 as stated looks too narrow. For one thing, rounding up or registering students on grounds of religious beliefs is a first-amendment violation, and so covered by 4. In the event (I hope unlikely, but we’ll see) that something like this happens, it’ll be on grounds of national origin or something similar. But unless you can think of a legitimate ground for the registering, rounding up or internment of students, you may as well leave out the “on the basis of their religious beliefs” bit, and just oppose registering, rounding up or internment of students, period.

2 is pretty much a commitment to open borders. Which is a defensible policy position, but can’t someone be, say, in favour of compulsory e-verify and the deportment of immigrants with felony convictions, while still being an ally against authoritarian tendencies in the government? (David Frum, or Reihan Salam, or on the left, T.A. Frank, all combine restrictionist immigration policy with strong opposition to Trump.)

4, as stated, is pretty radical. All surveillance, and all informing, under any circumstances? I’m quite keen on NSA and the FBI doing some surveillance to protect national security and combat organised crime, even if their actual current policy has the balance wrong; if I have solid evidence that my student – or my colleague, or my friend – is planning mass murder, I’m definitely going to inform on them. Again, there’s (I guess) a consistent principled opposition to all surveillance and informing ever (if you think the government is basically malevolent, say) but again, you can reject that principled opposition and still be an ally against authoritarianism.

To repeat something I said on an earlier thread, it is going to be important in the next few years to distinguish Republican policies that progressives abhor but which are democratically legitimate, from threats to liberal democracy that can be recognised by people anywhere on the mainstream political spectrum.

Sorry, typo: obviously “4, as stated” –> “5, as stated”.

I don’t think 2 is a commitment to open borders. One can commit to the two propositions without any contradiction:

1a. A state has the right to determine who is and isn’t a citizen and the prima facie right to enforce its immigration laws via methods that include exclusion and deportation (and maybe even marginalization, although I’m not sure about that).

2a. There are situations in which it would be wrong to aid a state in exercising its prima facie right to enforce its immigration laws via marginalization, exclusion, and deportation, either because the state’s prima facie right is outweighed by other concerns, or because the state’s prima facie right is not outweighed by other concerns but because aiding the state is impermissible for other reasons.

Not only can one plausibly commit to these two propositions – José Jorge Mendoza (and perhaps others) have published defenses of something like a conjunction of the two (Mendoza supports open borders but thinks that supporters of closed borders should still commit to 1a+2a). A good article on this topic is Mendoza’s “Discrimination and the Presumptive Rights of Immigrants.” The argument in that article is that the enforcement mechanisms for immigration policies, even if the policies themselves are in principle justified, can be discriminatory in objectionable ways, such that one ought not to support them. It’s not hard to imagine why this is the case, because these sorts of concerns are the reason why something like 2 shows up on the list. When Donald Trump says that Mexico is sending rapists and criminals and that he wants to deport 2-3 million criminals, the sorts of actions that would result from trying to effectuate that deportation wouldn’t be colorblind, if you know what I mean.

Just a couple of comments in response to David:

On 2:

2 isn’t a commitment to open borders. It’s a commitment to not “aid in the marginalization, exclusion, or deportation of my undocumented students and colleagues.” One can make that commitment and not be in favor of open borders, for:

(a) one might think that while there ought to be limits on who enters a country, those found to have entered the country illegally ought not to be marginalized, excluded, or deported. (Maybe they just ought to be fined.)

(b) one might think that while there ought to be limits on who enters a country, and that those found to have entered the country should be deported, they ought not be marginalized—treated badly, have their interest ignored, etc.—prior to having gone through the appropriate judicial proceedings for deportation, in which one might think professors ought not play a role.

(c) one might think that while there ought to be limits on who enters a country, and that those found to have entered the country should be deported, we have strong reasons to not convert college campuses into environments of increased suspicion and hostility. (This is a kind of division of labor argument.)

On 5:

I agree that 5, as stated, is unnecessarily radical. I imagine that 5, like the other clauses, were authored with a certain range of circumstances in mind, and with the implicit understanding there might be extenuating circumstances under which compliance would be unreasonable.

@Justin, @Danny Weltman:

I’m persuaded by these responses that my use of “open borders” to describe (2) is too sweeping – but I’m still inclined to think that (2) commits a signer to a position on immigration and immigrants that’s much stronger than is entailed just by anti-authoritarianism. To restate my example above, suppose (hypothetically) that I support mandatory e-verify, and deporting of illegally-present immigrants with felony convictions. That might reasonably be interpreted as “marginalisation and exclusion” (a student is marginalised, and excluded, to some degree if they’re unable to work) and definitionally includes deportation.

It’s not that I don’t get the point. Aspects of Trump’s immigration policy pretty clearly cross the line into authoritarian and inhumane, even for advocates of a much stricter immigration policy than current policy. But I don’t think the current phrasing captures that – it’s too broad. (I don’t have a good alternative, though I think Constitutional issues of due process and illegal search capture part of it.)

@Justin in particular: doesn’t your (b) violate (2) as stated? If X is in favour of deportation only after due process, X is still in favour of deportation.

More generally, 5 seems to be very broad. A lot of really important regulations (I’m thinking of the Americans with Disabilities Act, and many environmental regulations) rely on ordinary citizens informing authorities of violations. I assume that the author doesn’t mean to include those in the sorts of surveillance not to take part in. But I have seen some people endorse very broad versions of 5 where they’d rather not report *any* crimes to the police, in order not to be complicit in the problems of the existing law enforcement system. And there are other existing controversies around mandatory reporting for cases of suspected child abuse or sexual assault.

1 and 3 seem oddly narrow. How about

1. I will not aid in the registering, rounding-up, or internment of students and colleagues on the basis of their beliefs. (Without limiting this to religious beliefs).

3. I will, as my capacities allow, discourage and defend against bullying and harassment. (Without specifying who will be protected).

By all means, we can say more to express our particular concerns for, say, Muslim Americans, while still having our rules provide more coverage.

I still want to hold out for:

“I will not aid in the registering, rounding-up, or internment of students and colleagues.”

Fwiw (I don’t claim any particular authority here), what Danny Weltman and Justin W. said. You can’t deport 3 million people fast, let alone 11 million, without absolutely massive violations of US law and human rights — so 1 and 2 above are meant to hit home as the core cases of which 3 is the generalization. (And the whole is indeed meant to be something a decent conservative could sign on to, including someone pretty opposed to illegal immigration.) Likewise ‘inform’ is a deliberately ugly word, and meant to pick out the same set of contexts, in which you can tell you’re being asked to do something you really shouldn’t. That’s totally compatible with continuing to call in hit-and-runs or whatever.

I deliberately left the phrasing fast and loose (DN actually made it quite a bit more formal, which is fine, it’s their blog) because I don’t think there’s any point in trying to forestall philosophical nitpicking (and I say that with love) in a text like this. Better to make it obvious that you’re assuming charitable interpretation, sensible contextualization, common sense limitations of scope etc. by the reader. That kind of makes an ethical point in itself — and anyway the important ‘reader’ is you yourself if you decide to adopt it, not some uncharitable third party. So, read it (or revise it) in whatever way makes sense to you….

That’s helpful, and sensible.

whoops, make that 4 is the generalization

What exactly is the point of the code? Is it meant to help remind us of our commitments by having a handy checklist at hand? If so, number 1 seems redundant. It is hard to imagine professional philosophers forgetting that they need to resist aiding in the rounding up and internment of religious minorities. It is a bit like mentioning that we shouldn’t join the Nazi party or roam the streets beating up Muslims.

On the other hand, I would like to suggest:

11. I will keep in mind that my job is to help students to think for themselves, and not to guide them to what I think are the correct views.

12. I will keep in mind that my views need to be critiqued and questioned, with objections listened to and considered. I will not dismiss objections by disputing the authority of the objector (unless they appeal to their own authority as part of their argument).

13. I will keep in mind that every limit we put on our students’ freedom, both in what we require them to do and what we require them not to do, comes with a cost. The cost may be worth it, but must not be forgotten about.

14. I will encourage my students to critique views that I think are correct, and will ensure that they are familiar with the objections against those views and can convey the objections as charitably as possible.

There’s a bit of overlap there. Ah well.

I’m just curious, Prof. Rachel Barney, where did you first write these? I’m seeing the Daily Nous and InsideHigherEd write-ups, but can’t seem to find an original posting.

Prof. Barney emailed them to me for publication at Daily Nous. To my knowledge they were not published elsewhere previously.

Thanks for that explanation. Glad I came across these — and the discussion. -Randal

For number 3, either remove the list, or add political orientation and political affiliation to the list. You state in your comment to another post that

“on 3: political beliefs and opinions are not included in 3 and I did not add them because (a) I don’t think the way they contribute to a person’s vulnerability (when they do) is usually comparable to the ways in which race, gender, and sexual orientation contribute to a person’s vulnerability and (b) political opinion is discussed in 8 and 10. (Of course, things could have been arranged differently.) ”

In response to a….There have already been students beaten for voting for Trump in mock elections, and conservative students are regularly belittled by open letters and comments by people in power in academia. So yes they contribute in the same way to a person’s vulnerability especially within an environment where they are clearly the minority. Diversity of ideas must be protected and celebrated.

In response to b…8 is general and does not specifically include these groups. I would be ok with 3 being made general as well. I think that it is important given the current toxic environment on campuses toward conservatives that section 10 remain.

For section 5, if you are at an institution with federal grant funds, you have a responsibility to report fraud to the federal agency giving the support. For example, if a researcher with an NSF funds misspends those funds, you must inform. This section is far too broad. As written, if someone, or some department violated federal civil rights laws, you would not inform. Faculty, staff and students are called to follow local, state and federal laws. As a citizen if you see a crime, you are obligated to report the crime. As written, you are encouraging your faculty to turn their back on law abiding individuals and the general peace that follows when we all act according to the laws in our country. Would you turn your back and walk away from a lynching and say you will not inform? This statement supports anarchy which is not acceptable and should be eliminated.

For 7, it is challenging to know what you mean by truth. If you were being objective, you may understand that we do not have a good grasp of what is true. As a scientist, I find papers every year that shake up ideas that were published the prior year. I suggest deleting the term truth from the list. We seek truth, but none of us has reached that point yet. For example think about what we teach concerning the building blocks of matter or the basic ideas surrounding black holes. Is a panda a bear, or more like a racoon? What is light? Even ideas about human history changes as more evidence is discovered and/or considered as evidenced by the new information about the terracotta warriors in China.

In general I think that it is important to think carefully about the language that is used so that it will be helpful no mater how the political and social climate changes outside of academia. Listing of specific groups or classes of individuals may not stand the test of time.

Melissa, there is a big difference between defending a person and defending an idea. A person’s birthplace, sex, race, and orientation are immutable. Their ideas are not. As you so aptly point out, ideas are supposed to be subjected to scrutiny, shared with others, compared with evidence, and challenged by competing ideas. We can and should give all ideas (be they political, religious, or scientific) a voice and a defense, but you can’t make all Ideas of equal value. The ones that stand up to reason, contribute to the well being of humanity, and are supported by facts should advance, the ones that do not should be marginalized or retooled. You can’t make liberalism or conservatism a protected class. They have to survive on their own merits and those that espouse them have to be willing to defend them in the face of opposition. The threat this code of conduct is in response to is a threat to people, not to liberalism or conservatism. And frankly, now is the time to return to looking for the facts and the evidence in the face of an overwhelming fountain of misinformation, lies, and misdirection. The ideas with merit will survive the truth, even conservative ones.

If that were correct, it would also call for removing religion from the list. But I think it’s simplistic. There’s a difference between serious – even highly critical – engagement with ideas in the context of an active discussion of those ideas, and hostility and dismissal of a person on the basis of their views, in discussions about unrelated matters.

Dear Robert,

Religious ideas are by definition part of faith and are not designed to involve reason or be supported by facts or to be subjected to scrutiny. That you would address all ideas like we address scientific theory or laws suggests that you have an implicit bias about what it means for an idea to be valid. Faith is different from science and to see science as being superior to faith is just one way to look at the world. If a student has a different world view, their whole existence will be marginalized by this approach. Many items that conservatives fight for politically have to do with their religious convictions and can not be dismissed away so lightly.

I would say that a person is, essentially, a collection of their beliefs and ideas. If you dismiss or marginalize their ideas, you have marginalized them. Furthermore, sex is clearly not immutable. What would you say to the transgendered student who has the “idea” that they are male when the biological facts as we understand them such as the shape of their external features and the results of genetic testing say otherwise? Would you refute his understanding of himself? Gender and race are social constructs as is religion and political affiliation. All of these are ways in which individuals self identify into social groups. I do not see one way of organizing one self as being superior to another. We need to respect all people and quite trying to say that some people are more important to embrace than others.

Academia is a hostile environment for individuals who do not hold specific political views, and this needs to end. We need to be more welcoming of individuals who believe differently than we do. If we keep asking for tolerance by the right for the ideas that they find challenging, then we must be just as tolerant of their diversity of ideas.

How do you want to handle beliefs like “vaccination causes autism”, “prayer is an effective form of medicine”, “white people are more intelligent than black people”, or “God wants me to kill blasphemers”?

I agree with you that academia has a big problem with being hostile to the politically unorthodox, but that’s compatible with thinking that good ideas should triumph over bad ones. Indeed, the biggest benefit from allowing the politically unorthodox to speak freely is that they might have some good ideas.

I will try to address each of these.

How do you want to handle beliefs like…

“vaccination causes autism”, This anti-science and/or pseudo-science idea does not seem to be related to any of the typical protected groups and is a phrase that is probably more likely to come from a political group namely someone on what is called the far left in the US. This is one of those items often ignored because it does not fit the narrative that anti-science comments come from practitioners on the far right. I think it is helpful to help students to understand the development of this idea and to provide them with the research findings that have shown this to be untrue. It is also helpful to do this within the context of the developmental trajectory of autism especially as it relates to the typical timing of vaccination. This statement is a good starting point to discuss the pluses and minuses of vaccination for both the individual and the group. Vaccinations are only effective within the group contract for each individual to take on a smaller risk to protect all from the larger risk. There are many teachable moments within this comment that do not require one to state that this comment is or is not true, but rather to allow your students the opportunity to discover the validity of the comment as part of the learning exercise. This idea is important as a public health issue and should be addressed.

“prayer is an effective form of medicine”, Some religions practice this and so if someone practices that religion one should be respectful of this component of their faith. It may be surprising to some on this discussion that research has shown that being part of a community of faith shows positive health outcomes and there have been studies showing positive outcomes from prayer. How these outcomes occur, is not clear so they could be due to increased social support or other factors. Some may argue that there comes a time for prayer in that there is nothing for modern medicine to offer and at this point, pray is the best form of medicine because it is serving the caretaker. If you dismiss this comment out of hand as hokum, you miss the opportunity to discuss prayer within the context of a variety of supplemental treatments such as meditation. It is important to acknowledge the idea and discuss the pluses and minuses and to understand the social context of the comment. While this idea may seem to be a personal choice, the question becomes more complicated when the patient is a minor and so it has legal implications in terms of how the state intervenes in the decisions of how families choose to live. If you bought into number 5, you would not interfere with that parents rights and would not report them to the authorities.

“white people are more intelligent than black people”, This would be an opportunity for a teachable moment about differential opportunities, test bias, stereotype threat, etc.

“God wants me to kill blasphemers”? This should be taken seriously as a threat and reported to the authorities. I do not care a hoot about number 5 for a comment like this, it is your responsibility to report any ideas that suggest that the person is a danger to self or other. I would not suggest engaging in a discussion but would rather suggest bringing in someone with the training to deal with this. While this could be loosely classified as a religious thought, it has much more immediate public health concerns that are not able to be handled in the classroom.

Not all ideas can be ranked as good vs bad or that one idea is better than another in all situations. Often times a solution is situationally specific. To me the idea that ideas can be ranked is similar to the idea that some species are better than others….ideas like species are better or worse suited to their environments.

“What is light?”

It’s the massless gauge boson of quantum electrodynamics, which is an effective field theory applicable to lengthscales above 10^-18 meters, and which has been tested to accuracies of one part in 10^9. That theory was worked out in outline in the late 1940s, and while future developments over the subsequent 65+ years have deepened and enriched our understanding of it, they haven’t invalidated any of the original insights.

On a related matter, “truth” in (7) looks fine to me. Nothing is certain, and much is highly contested, but plenty of things are pretty damn solid.

Dear David,

The point I was trying to make is that, as a scientist, I do not think that using the word truth adds anything to the point in section 7 and just brings up larger philosophical questions concerning the term truth.

Hi David, curious what fields of study you engage. (I’m a topologies by trade.)

Topologist

Anti-authoritarian? Sounds like you are suppressing speech and dissent in the name of freedom. Rather Orwellian.

BTW, my grandmother was one of the first women to graduate from MIT (in architecture).

I think such a formalized code is an excellent idea. Maybe there could be some symbol that academics who subscribe to this code could wear, like a more meaningful version of the dumb safety pins? Perhaps a scarlet A, for anti-authoritarian?

There are a lot of good things in this list. There are a few adjustments I think should be made, though, before I’d hang it on my office door — here are a couple immediate thoughts:

— #1 deserves to be on the list, but I don’t like leading with it. It’s a statement about an extreme hypothetical. My objection is not that I don’t think this hypothetical could become real, but rather that it’s not where I want to *start* setting the bar. In suppressing a population segment, I think the authoritarian regime would start with harassment and build to register/confine/deport. We’re already in the harassment phase, and I would want to make it clear with this list and we are fighting that starting *now,* not somewhere down the line in the future if they starting rounding people up. To this end I’d like to see a rewording of #3 lead the list. This is also the aspect that I most want my students to know I will defend, and makes sense for them to see first.

— I agree with some of the other opinions that #5 is troubling, as “surveillance” and “inform” apply to several types of circumstances. Informing is whistleblowing, and we all recognize that there are a lot of circumstances in which whistleblowing needs to be protected. If a department is covering up / protecting a sexual predator who has victimized students, someone absolutely needs to blow the whistle. (That one wouldn’t go to federal authorities, but for those of us at public institutions it could likely go to a state government entity.) So essentially what we want to say is that we will “inform” pertaining to rules that we agree with, but not for the ones we don’t. The only way we could defend such a stance is to give a bit of description about what are the types of policies that might fall in the second category.

Love this!

After researching things a bit, I wrote my own Code of Conduct, based on the Anti-Authoritarian Code of Conduct, as well as several others, “the Anarchist Code of Conduct.” Just added it to my 1,000+ star’d GitHub project as its official Code of Conduct: https://github.com/bradvin/social-share-urls/blob/master/CODE_OF_CONDUCT.md