We Have Work To Do

On Friday, January 20th, 2017, Donald Trump will be inaugurated as the 45th president of the United States of America.

Though there were some warning signs (Brexit, for one) and some consideration of the prospect (see #5 here, for example), not many people predicted that Trump would win the election. Certainly very few people in academia thought he would win.

But he has won. I find this horrifying. And while the expression of horror, fear, sadness, bewilderment, anger, and so on, is perfectly appropriate, I want us to here focus on a different question.

The question is: what should we do? By “we” here, I mean we in our capacity as members of the community of professional philosophers.

We can reach more people, and do a better job teaching our students.

Here are three contributions to Trump’s success that philosophers and other academics can address in their courses and engagement with the public in a largely nonpartisan way:

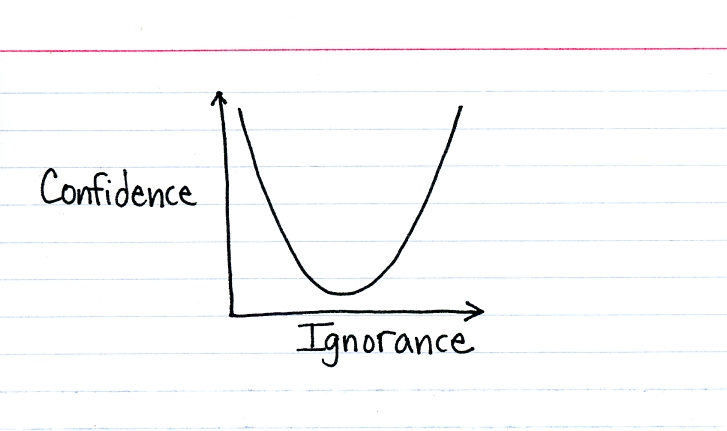

1. Lack of respect for expertise. One glaring hallmark of Trump’s campaign is his apparent lack of respect for expertise, and the concomitant belief that the relevant questions are simple and their answers easy. The confidence with which he expressed his detail-less assurances that he could offer “tremendous” solutions to problems it was quite clear he did not understand ought to have been a bright warning sign. Philosophers are in the business of showing how the apparently simple is really quite complicated, once you think about it. This point is applicable across nearly every domain, especially governance and the various political, economic, and social challenges that governments address.

2. Inattention to sense. Is it that people don’t know when what they’re hearing doesn’t make sense? Or do they not care? Or do various cognitive biases interfere with people’s understanding of what makes sense? Yes, yes, and yes. Philosophers have long placed careful reasoning among their pedagogical goals. We need to do a better job of that, though. And we need to take up the task of motivating rationality. We academics—philosophers, especially—don’t generally need to be motivated to try to think rationally, but we are not normal. Additionally, we need to incorporate into our courses findings on the biases that interfere with proper reasoning, along with debiasing strategies.

3. Focus on the visible, rather than the important. Part of Trump’s success was owed to his ability to paint challenges as conflicts, and then foster solidarity with potential voters against their “enemies.” Yet the construal of these conflicts works by drawing attention to superficial and ultimately unimportant differences, and ignoring underlying and more important similarities. Insofar as philosophers teach others to look below the surface, and to not take things simply as they appear, they have a role to play in undermining some divisive appeals. Merely drawing attention to the pervasive role of chance or luck in everyone’s life can get students to be more thoughtful about the kinds of problems governments tend to address.

There is more that could be said about each of these, and I’m sure that others have different answers to what we should do. Please share them.

We have work to do, people. Let’s figure out what it is and how to do it.

I would hope that if you are American, shame is a large part of what you are feeling right now. The world has become a markedly more nasty place overnight, and your nation made it so. I hurry to add that a lot of countries have contributed to this, and my native country of India is one of them, with its election of a bigoted party and Prime Minister. But we all need to feel some sense of personal responsibility when the groups to which we belong do really horrid things.

There is a philosophical question, however, of what it means to belong to a group, to be complicit in the actions or intentions of said group, and how we want to talk about personal responsibility for the actions of (only half the members of) a group. There is an existing philosophical literature on these topics which might be helpful in thinking about group blame and responsibility.

As of nearly 24 hours after the polls have closed, more than half of voters did not choose Trump. The majority chose Clinton. A very small minority chose third parties or write-in candidates. Yes, those who did not vote have a roll. Yes, those who voted but did not persuade their fellow citizens to join them in voting for Clinton have a roll. Yes, there are shortcomings of the electoral process, voter mobilization, inspiring and informing potential voters. Those are things we all can do better at as citizens. But I do not feel ashamed for having voted for Clinton and against Trump, nor personal responsibility for the electorate having selected Trump. One might also wonder if the voters who supported Trump and those who supported Clinton even understand themselves to be part of the same group as it stands today on November 9th, or if there are radically different, and perhaps not-at-all-overlapping, views of what it is to be “American” in this country at the moment. The answer to that might help us determine what responsibility we (each individually and in collectives) take in changing our country moving forward.

The Electoral College is a moribund institution and ought to be eliminated. The Founders created it to protect the country from the ignorance of the average voter of the day so that horrible choices could be countered by the more informed electors. Can we say, “now is the time for electors to vote for sanity?” Let us not fool ourselves into thinking we live in a democracy, we are a republic with majority rule not being the case.

The problem of collective responsability has a interesting approach considering the “moral luck” perspective. The famous article written by Nagel can be helpful: we tend to blame all the people that in a country which done a bad thing. But many of the same people disagree with it (like Clinton voters). Are they blame too? Moreover: they did not -chose- to have this decision. It is just a matter of being a(n) (un)luck citizen in a awful political moment.

What’s interesting about shame, I think, is that it doesn’t imply responsibility. You certainly don’t have to be ashamed of your vote. My suggestion is that you should feel ashamed of your country. A lot of Germans know what that feels like, and I said that as originally Indian, I know it too.

An important background issue to each of the three you raise: becoming better teachers. We have an infamous reputation for arrogance, inaccessibility, and taking a pedagogically sadistic delight in showing our students (and others) how difficult our questions are and how tough it is for others to even understand them and doing so without an attendant effort to make them genuinely understood. What we do is important. But as a profession we’ve put far more effort into robustly working through philosophical questions than we have in communicating them (i.e., being good teachers).

I agree that more needs to be taught on expertise, as well as on disagreement. But let’s teach it in a way that matters and which speaks to students. I remember reading a Philosophy Compass article on disagreement that basically ended with “This is a relevant topic for politics, but we don’t really focus on that.” The world needs discussions about how we know things. But no more fake barns, or split checks, or some other bullshit. Socrates would be ashamed, I think.

The response seems to be: we knowledgeable people must better teach the ignorant.

The response should be: we knowledgeable people must understand why the ignorant believe the deck is stacked against them. We must LEARN from them. You will never convince anyone of anything, unless you persuade them that you are willing to take them seriously and learn from them, even as they learn from you.

this is a really important point.

some of timothy burke’s tweets are helpful here, too:

https://twitter.com/swarthmoreburke

This. This really seems to be an important point so much of “our side” misses.

Numerous and colossal political and social failures have lead to this day, and one of those is the apparent unwillingness of one side to listen to what the other side is saying; rather, we say “oh no, you say ‘x’ but *really* you mean ‘y'”.

Please, if arrogance is one of our failings, let’s not always conclude that if voters pick someone we decry that they did so out of ignorance. It is this attitude amongst elites and liberals (of which I count myself) that turns off the “average voters”. “They just don’t understand” or “they aren’t informed enough”, are cop outs. The average voter, and my mother and father, grandparents, etc… fall into that category, having only high school educations or less (due to the depression), were astute and understood what was at stake in every election they voted in. I take it that this is true of most voters from the non-elite classes, who were the people I grew up with in my old Chicago neighborhood, mostly blue collar ‘salt of the earth’ types. We academics have to stop attributing disagreement with our views to ignorance and stupidity. We need to understand that average voters are the majority and ought to be taken seriously and treated with respect, rather than dismissed as uninformed and ignorant, which most are not.

An interesting standpoint and one I haven’t read often.

A few questions, if you don’t mind?*

Would it be beneficial to promote arguing for truth instead of arguing to win?

That is, would it be better to teach someone the tools, (or possibly how to create new tools) we have to seek the truth instead of trying to teach someone why they are wrong?

That might be a tough seed to germinate within any group, though, I suppose?

*If your answer to this question is, “I do mind”. You can skip the rest.

It seems significant that no academic I know expected a Trump victory. Part of this was because the polling suggested otherwise, but part of it also seems to be that our own experiences suggested that there were not very many Trump supporters around, which means that our interactions are limited to a population which doesn’t represent a significant portion of the US population. As such, it seems as though one way to effect positive change is to consider how our discipline might expand our circles of influence and connect with other individuals. Put differently, much of philosophical outreach (since it happens in a classroom) seems to be an instance of “preaching to the choir” as it were. This seems a significant impediment to some of the work Justin outlines.

This may be true in elite universities, but those of us who teach in ordinary schools should realize that we do have a number of Trump supporters in our classes.

Excellent comments. Especially ‘preaching to the choir’. Us academics need to expand our circles of contact with people outside academe, rather than talking to others only who agree with us. I, personally, cannot think of a single person I talked with this election year (wait, one, my error) who thought Trump was the better candidate or who was going to vote for him (and the one who thought he was better was not going to vote for him or Clinton).

I can’t say I wasn’t hoping for a Clinton victory; I was. But I can’t say I was stunned it didn’t happen.

I think the difference is that only about half of the people I spend time with are academics; the rest I know through church, and my church friends were all over the place in their votes: some were phone banking for Clinton, some were Bernie holdouts, some voted for Evan McMullin on principle, and yeah, some voted for Trump, with reservations. And we could all talk about politics with some passion but without mutual suspicion.

I think it’s true that most academics spend time only with the very like-minded. It’s understandable; not only is work the easiest place to meet people, but our professions also form us, so that it becomes easier to talk to other academics and especially other philosophers than it is to talk to anyone else. This insularity does however starkly limit both your perspective and its impact.

This is incorrect. A number of academics said that Bernie Sanders should be the candidate because Trump would beat Clinton.

One of the weirder things was that if you were full of dread and sure that Trump would win, you were marked as a lunatic, or a left-lunatic or something of that sort.

It became difficult to speak openly of the issues one saw, after a certain point.

I applaud Justin’s three points. I would like to add, though, that we must not be content with just teaching our students. We need to do a much better job of reaching out to the population in general. Philosophers argue endlessly about politics, but generally, we talk to one another and speak only to those with whom we already have broad political agreement. We need to take seriously the importance of communicating with those outside the ivory tower.

Well, I expected a Trump victory. I grew up in a right-wing evangelical context and am more intimately familiar with that perspective than a lot of my peers. I was hoping my pessimism was wrong. When a single issue dominates (abortion, for many), there’s not much that can sway people.

I think that listening to the concerns of people of color, of LGBT citizens, and others who are more threatened by this election than (statistically speaking) the average philosophy professor is a good start. Full disclosure, I’m a “T” myself and fairly nervous about the implications of this election for myself and some of my friends. Mike Pence–let’s face it, he’s going to be calling a lot of the shots–is frightening and I saw a lot of threatening discussion about enforcing gender norms during the election. And for people who are not white and LGBT, this is serious stuff.

The very worst and most painful thing about sincere pessimism is the ever-novel rediscovery of being right—and I suspect that you and I, among many other pessimists, will have ample occasion to be right throughout the near future.

Yes, we’ve seen this before, and we’ll see it again. (This slows me but mustn’t stop me.)

Academics (and the intellectual left more broadly) need to do a better job of understanding how the vast majority of people in this country live, how they think about morality and politics, and what matters to them. There are many reasons why we fail in this regard: If one spends one’s life going from one level of elite schooling to the next, as academics now almost always do, one never encounters people different from oneself. And, despite the ubiquitous talk about it, there is little diversity in academia, at least of the kind that matters: which is a diversity of perspective.

I happen to know some Trump voters (every veteran does, I am sure), and here is something about them that may surprise you: They are good people. Many, most, perhaps almost all of them. They are not racists, they are not bigots. They are not dumb.

They are, however, people who have been at the losing end of economic redistribution since 1980; they are people who used to be able to provide a better opportunity for their children through their labor, but now face immobility; they are people who would like to be treated with a modicum of charity from elites like us, but instead receive only our contempt. It is hard to overstate the (reasonable) anger and resentment that gets stoked in a person when you label her a racist or an idiot on the basis of a perceived group trait (cf. “all blacks are criminals”), or when you mock the deepest values (of family, religion, etc.) around which she structures her life.

I suspect that one of the worst moral consequences of this election is that those who have already suffered from so much economic injustice over the past decades–many (most?) of them Trump voters–will find their prospects even dimmer under Republican political control. Philosophers, side-by-side with social scientists, need to do a better job of explaining, in a way the regular person can understand, what a more just economy looks like and the policies that get us there. As of now, when this person looks to intellectuals for guidance he finds only blather about Halloween costumes and “safe spaces”. He finds, that is, people demanding that more of our scarce resources be spent on those already blessed by extraordinary privilege, and he finds this outrageous. And he is absolutely correct.

The march of progress is an unsteady one; maybe some good will come of this result, in the long run. But for now, as someone who loves his country very much, it is a terrible embarrassment.

“They are not racists.” But they are the kind of people who will vote for someone who is a racist.

“They are not bigots.” But they are the kind of people who will vote for a bigot.

“They are not dumb.” But they are the kind of people who will vote for someone who has never in his life done anything to help them, and who does not support policies that will help them economically.

“They are angry and resentful.” But since when is that a good excuse for immorality and stupidity?

And that is an attitude that will poison your attempt to understand Trump voters. You cannot see beyond your own worldview.

Didn’t we learn in the ’90s not to make broad assumptions about people based on their blog comments?

Surely there’s room for nuance here?

If history teaches us anything, it teaches us that most of us would vote for a racist or bigot under certain circumstances. I think that does make us racists, but I doubt it makes us racists is the pejorative sense you’re using.

“[S]ince when [are anger and resentment] a good excuse for immorality and stupidity?” Maybe never. But justified anger and resentment can at least mitigate blame, even when warped and misdirected. This is particularly true when, as in the present case, those who are angry and resentful are victims of serious epistemic injustice.

I didn’t call them racists or bigots! But I did want to point out that saying that they’re not racists or bigots (even if true) is not as exculpatory as I took Thomas M. to be suggesting. And I also wanted to point out that even if we thought it would be somewhat exculpatory to vote a bigot or racist into office if it were in one’s interests to do so, that condition did not generally obtain for the population Thomas M. was discussing.

“I didn’t call them racists or bigots!”

Ah, sorry! Like many of us (I’d think) I didn’t sleep last night, and my implicature skills are probably far from their best.

But Justin, surely you are still missing the point in a spectacular manner. Normativity (rational or moral) does not govern our country. Rather, individual citizen’s beliefs and actions (e.g., voting) do. I could be mistaken, but Thomas M. was not (or did not need to be) making a point about moral excuses or blameworthiness. He was offering an explanation. Perhaps a psychological explanation, but something non-normative, in any case. If we want to enact a change, we need to understand what went wrong. That requires meeting poor white “racist” “bigots” where they are at, and figuring out how to work from that reality, not from some moral high ground.

Your post, while I appreciate its passion to do something, is as Thomas M. suggests, importantly missing the mark. Our moral glasses are exactly what led us to discount the concerns of these voters because they were irrational or immoral. I don’t think the right approach is to try to “fix” these “broken” people by teaching them how to care about things they don’t care about, like those things your original post suggests. Maybe that’s valuable, and an important part of creating an educated population. But that mindset still views these people as though they are broken in some way. What if instead, as Thomas M. and Arthur Greeves seem to suggest, we meet these flawed-but-actual human beings and listen to their concerns and take their concerns seriously **even when they make us uncomfortable** (e.g., “These fucking brownies ruined my town and stole my job.”).

Your post is also troubling to me because it appears to assume that these people were being irrational or stupid in what they did. What if instead their decision was exactly the correct thing to do for them? Framing things this way, we see the hurt and pain behind these humans who made these decisions. I would rather feel empathy toward these voters and try to work with them to find solutions that are acceptable to the pluralistic community at large and that mitigate their pain. I would rather do that then view these people as broken or stupid.

To add clarity: I’m intending to speak of the voters who were not already a foregone conclusion. There are some deeply bigoted citizens, and what I’ve said won’t make sense regarding them. I’m speaking instead of the more situational bigots. In shorthand, I’m speaking of the Boston cop who quietly despises black people for ruining his neighborhood or the union worker who hates brown people because his world crumbled 15 years ago and now he watches Fox News. Will some people be hateful bigots because for whatever reason they sincerely believe that non-whites are genetically inferior? Yes. Will some people be hateful bigots because they are poor, hurt, scared, and were left behind by their nation? Yes. I’m talking about the latter.

“What if instead, as Thomas M. and Arthur Greeves seem to suggest, we meet these flawed-but-actual human beings and listen to their concerns and take their concerns seriously **even when they make us uncomfortable**”

Nothing I said is incompatible with this. I am in complete agreement that we should listen to them and take their concerns seriously. We can do that and form opinions about the wisdom of their electoral choices, too, no?

“We can do that and form opinions about the wisdom of their electoral choices, too, no?”

Your original post seeks to change their choices directly, rather than seeking to change the world in a way that would indirectly change their choices. That fact suggests that your original mindset differs from this backtracking I’m sensing when you suggest that all you were trying to do was have an opinion toward their choices while still taking their concerns seriously.

If you’re referring more narrowly to your earlier comment on this thread, I have to refer you back to my original post. You’re welcome to have an opinion on these voters’ electoral choices, but that opinion you offer may be part of the original problem that fed into those decisions, it may match the world poorly, it may be largely irrelevant to how the political process works, and it may indicate other beliefs that will get in the way of making fruitful progress in the future.

If all you’re saying is that you’re allowed to have an opinion…sure. But this is a discussion thread, so the response you’re giving in that context is a discussion killer. I thought that part of a discussion is the evaluation of the accuracy and usefulness of different opinions. (Notice I did not include “value judgments of different opinions.)

“Your original post seeks to change their choices directly, rather than seeking to change the world in a way that would indirectly change their choices.”

My original post highlighted three problem areas for philosophers to address in their teaching and outreach. These are problems that I do think contributed to Trump’s election, and I do think Trump’s election is terrible for the US and the world (and terrible for many of his voters, especially). But they are also largely nonpartisan problems that any academic should be concerned with. Further, they are problems for the very people you seem to think (for some reason I’m still not clear on) that I’m unconcerned with.

You seem to think I’m unaware of or unconcerned with the problems that poor Trump voters face. I don’t know why you would make that assumption. Certainly that does not follow from my thinking that they made the wrong choice.

Maybe your concern is that I’m suggesting we go around and tell poor Trump voters that they are stupid and evil? Such a course of action does not follow from my thinking that they made the wrong choice, either. Certainly doesn’t seem like an effective strategy to me.

Maybe you think that education and improved reasoning alone won’t solve all of the problems that poor Trump voters face, and that there are other things we should do. I agree, and again, a denial of that does not follow from my thinking that they made the wrong choice.

Recall that in my original post I said the following: “I’m sure that others have different answers to what we should do. Please share them. We have work to do, people. Let’s figure out what it is and how to do it.”

I think you’re reading into my post a kind of comprehensiveness that I explicitly disavowed.

And let’s be honest here, Justin: many academics ARE letting the end justify the means, when it comes to calling people “bigots” if they refuse to use novel pronouns, to use one example, or in calling people “racist” for opposing affirmative action. Do we expect liberals to be able to use unfair rhetorical devices on the verbally helpless masses, but then also expect the masses NOT to find recourse to whatever “strong man” they find who can cut through the verbiage. Trump is a hero to these people precisely because he does not fall down and play dead whenever the SJWs attack him.

I cannot stand Trump, and I fear for my country. But I blame the Academy for Trump, quite as much as I blame his voters.

Do most ordinary Americans even follow stories about academic PC? My default assumption is that everyone outside academia mostly ignores it.

A stroll through YouTube channels would leave you morbidly surprised about that.

Hardly an indication of what most people are paying attention to.

On the contrary, it directly answers your default assumption that “everyone outside academia mostly ignores it.” They don’t, and the number of Americans livid or put out (rightly, wrongly, or both) with liberal academia and the woes of its political correctness is far higher than you’d think. In many cases the hostility to it is slightly obscured by (a) academics’ own predominant lack of direct contact with and indirect knowledge of their critics; and (b) the fact that their critics often lump academia into an entire swatch of American culture that they see as glutted to overflowing with trivial nonsense.

I’m guessing the citizens of North Carolina noticed these attitudes, when Charlotte created a bathroom ordinance that (for better or worse) stemmed from the Ivory Towers of higher learning.

As someone whose relatives and close friends (besides fellow academic friends) are almost all, to a person, poor folks from Alabama outside of the academy, you’d be surprised. The Yale incident last year was a hot topic, even though it had literally no effect on any of their lives. Colleges and universities are a huge topic of discussion for these people because they realize that’s where the elite, PC culture is being created, and they also realize that it spreads from the Ivory Tower to affect everyone’s day-to-day life. Stuff like the bathroom incident in NC earlier this year spreads like wildfire, even among those not at all connected to the academy.

Err this attitude is certainly a contributing factor to point #1 in the OP, populists are having rhetorical success denouncing/defying experts and expert opinion at least in part because of the perception among a large swath of the population that academics have nothing but utter contempt for them and their concerns.

Granted I’m not an American and both anger and dismay at a Trump win is entirely understandable, but long-term rather than sarcastic contempt it is probably worth seriously asking “Why did people who are not bigoted vote for a bigot?” etc. A willingness to caustically dismiss half your fellow citizens and their views/concerns is a significant factor in the rise of Trump (I believe Taibbi at Rolling Stone had a similar take after Brexit “The Reaction to Brexit is the Reason Brexit Happened” and that general line of argument is relevant here)

“it is probably worth seriously asking “Why did people who are not bigoted vote for a bigot?””

Agreed, and didn’t mean to suggest otherwise.

Sorry, Justin, but what did you mean to suggest? I’m a little confused at this point since you seem to just be playing the rhetorical field. Was there something aside from the your view that Trump voters are immoral and stupid?

Wow Justin. The point of Thomas’s comment went right over your elite head. “immorality and stupidity”?! And we wonder why ordinary ppl don’t like us.

Has there never been a time in history when ‘ordinary people’ were guilty of immorality and stupidity? Is this mysteriously confined to the dreaded ‘elites’ for some reason? Or is it just always wrong to ascribe immorality and stupidity to ordinary people, regardless of what evidence you have for it?

I think it is wrong to ascribe those traits to any mass group that is surely made up of very different people, with very different moral and intellectual traits. This would be wrong, say, if the group was “ordinary people” “academics”, “women”, or “ethnic minority group such and such”. Surely philosophers find this sort of thing wrong? That is, it is wrong to attribute negative traits to an entire group based on what might or might not be features of a few?

Well, what if it’s a feature of many members of the group, and the group identity is a chosen one? Both those things seem true of Trump voters. And we’re only saying that they have displayed those bad traits one time just by this one collective action. We’re not making a generic claim about them.

“Maybe your concern is that I’m suggesting we go around and tell poor Trump voters that they are stupid and evil? Such a course of action does not follow from my thinking that they made the wrong choice, either. Certainly doesn’t seem like an effective strategy to me.”

Unfortunately, although few are going around saying this in person to Trump voters, it’s being said constantly in public contexts and Trump voters are fully aware of it.

The problem goes back to the left’s earlier decision to privilege identity politics issues and to marginalize class issues. Part of the problem is that we spoke truths that some whites don’t want to hear. But another part is that the left has, as a result of several theoretical confusions (e.g., white fragility), decided to embrace anti-white racism and misandry. Thus we find the HuffPo, Slate, Jezebel, Buzzfeed, and other prominent identity politics sites relishing opportunities to rub in negative (sometimes true) stereotypes about whites and men. Generics of the form “white people do this terrible thing”, “white people shut up”, etc. are thrown around with no regard for data. It seems to have become a point of principle not to qualify these generics with ‘some’ or ‘many’. The desire to confront white people with their misbehavior has displaced the search for effective means to bring about change. I mean, does anyone truly expect this discourse to reach poor whites? This also explains why so many commentators (Jamelle Bouie comes to mind) dismiss out of hand economic anxiety as an explanation of poor non-college whites voting Republican in far greater numbers than in the past: class explanations must be marginalized, for they are part of the racist past of class-first white populism. Furthermore, whites are incapable of economic suffering. The privileged (i.e., whites and men) are running racist, sexist, etc. software and nothing else.

I’m not saying the white privilege discourse is is the major cause of poor, non-college whites voting Republican in unusually high numbers. Economic anxiety has more to do with it and racism probable does too. However, it’s part of the story. If we want to build a coalition that can win in more states, that can re-take the house, and that erects a new blue wall, we would be wise to stop telling poor people to check their privilege.

Consider how easy it is to fall into intergroup bias and consider honestly whether it’s possible or likely that the identity politics discourse around white and men of the last five or so years has constituted those as outgroups and generated biases against them; and whether members of the ougroups are likely to feel it.

I know people will say I’m fragile and whites and men have it great so I shouldn’t complain. My response is that nothing that’s been said about whites has crushed me the way Trump’s victory has. If preventing that means talking more strategically (but still truthfully) about race, then so be it.

You just want to keep losing elections, don’t you?

Daily Nous readership is good, Daniel, but not that good.

🙂

I agree with a lot of what you have to say about listening to and not demonizing working class Americans. But we don’t need to give up our concerns about “Halloween costumes and safe spaces” to do it. Whether or not we think that such concerns are “blather”, we should all be able to agree that we need to do a better job of understanding, being concerned about, and communicating with the working class.

Echoes my comments in a post above. Cannot attribute ignorance and stupidity to those who disagree with us in academe. And, BTW, this goes for conservative academics who think liberal voters don’t understand the issues and are ignorant and stupid. Folks, we need to expand beyond our

books and theories, politics-wise, and address the public with respect. Then our job is to provide them with the logic and tools to make up their own minds, which many have already and chose Trump.

Good luck with that work as a community of professional philosophers. The Trump phenomenon — which could be seen coming for real (if not his actual victory) a year ago — can hardly be addressed through academic means, let alone philosophical ones. Basically, an electoral majority of the country is returning to its roots in the vain hope to “Make America Great Again [for White People].”

CNN exit poll data tell the story. Trump won the “white” vote 58 to 37. He won “white men” 63 to 31. He won “white women” 53 to 43. That Clinton won the overall “female” vote, 54 to 42, is due to “black” (94 to 4) and “latino” (68 to 26) women. Clinton won the overall “black” vote 88 to 8. Her campaign never grasped what such numbers would indicate. The community of professional philosophers probably can’t either. (Btw, Clinton won “under $50k” 52 to 41, while Trump won “$50k or more” 49 to 47.)

http://www.cnn.com/election/results/exit-polls/national/president

American values and priorities in full effect.

1) You’re assuming every black and Hispanic Trump voter publicly admitted as much to CNN

2) Related: the polls (both pre-eleciton and exit) missed this result by a yuge margin. Whence the faith in them now?

How hard did we try to talk to them? Not one political philosopher published a book devoted to Donald Trump in the run up to the election. Might have been a big seller. Maybe not, but who knows?

I take your point that the white electorate is being irrational. All the more reason to try to spread rational thinking to them.

There you go again, if they voted for Trump they were irrational. Stop it. I hate the outcome of the election, but please stop attributing irrationality to those who disagree with you. try, rather, to figure out their logic, accept it, and then take steps to logically address it. And, BTW, how quickly are books published so that academics could publish books addressing the Trump phenomenon? It began less than a year ago, my experience is publishing takes longer than that from start to editing to publishing. Unless, of course, one rushes into print for profit.

If someone has come to a different conclusion than me on an empirical question, then either we don’t have the same information, or at least one of us has made a mistake in our reasoning. Holding these voters to be irrational is compatible with figuring out their logic and working to logically address it. And if a book can be rushed into print for profit, why can’t it be rushed into print on the grounds that it is dealing with an urgent issue?

Whom to vote for is not an empirical question.

What the result would be of a Trump presidency vs a Clinton presidency is an empirical question.

“Btw, Clinton won “under $50k” 52 to 41.”

The important point is that Trump won the votes of many low income whites who voted for Obama (or even Kerry), particularly in midwestern and PA districts that allowed him to break through the “blue wall” and win the electoral college without the popular vote. Trump lost the low income white vote, but by a *much* smaller margin that Obama or Kerry. So we can tell ourselves that it’s just the bad rich white people who voted for him. Or we can work to win (much of) Trump’s low income white base back. I don’t see that happening until we acknowledge Trump’s relative (in historical terms) success with low income whites. This will mean complicating the simple-minded narrative that racism is the only cause of Trump’s victory.

I suggest we start by comparing how many people in the humanities and social “sciences” voted for Trump, vs. the popular vote, and consider the reasons for what I can only imagine will be a divergence exceeding that between whites and racial minorities.

No points given for reducing the answer to “racism,” “sexism,” etc.

There are a variety of reasons. The most important one is that we are better educated, so less likely to fall for Trump. Another reason is that few of us are working class and those with tenure expect to have jobs for life.

Many Trump voters are relatively economically secure.

What??? Another we are smarter than them answer that misses the issue. Are you also saying most academics come from the upper classes? I defy you to produce those stats. My 35 years in academe showed me most of my fellow teachers were from working class families. Maybe I wasn’t at an Ivy…

I neither claimed that we are smarter than Trump supporters nor that academics come from the upper classes. I said that we are more educated than the average Trump supporter and that few academics are presently working class.

I believe the best predictor of Trump votes is district white death rate (the higher the rate of white death in x’s district, the more likely x is to vote Trump). Pretty obvious how that accounts for the divergence.

Data?

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/03/04/death-predicts-whether-people-vote-for-donald-trump/

Insofar as Justin’s suggestions are applied to our role as teachers of philosophy, it seems crucial to say a word about classroom environments in higher education, especially regarding the social desirability bias. My experience has consistently been that this bias, inflated by the presence of an authority figure whose greater knowledge often thins dissent and stifles fierce interrogation by students, has a steady net effect of creating the appearance of far greater homogeneity than is really present. While the makeup of university student bodies, even in deeply red states, is well known to be slightly more liberal on average than the surrounding population—Donald Trump soared in counties where less than 10% of adults hold bachelor’s degrees—it’s easy in a classroom environment to miss how little we actually know about whether our instruction has effected any significant change among our students. Obviously this is not to deny that such change is possible, or that evidence of dramatic improvement in critical rigor and intellectual honesty can be found, but rather to underscore the difficulty of empirically squaring our methods and intentions with the actual outcomes of our teaching in real time. For all the discussion we may successfully invite and maintain on a given day’s class, and for all we may do to inculcate the importance of complexity, concern for evidence, and recognition of legitimate expertise, it remains a fact that we are painfully ill-equipped even in principle to gauge whether our students will do more than rehearse their prejudices when left to themselves again. Although a dispiriting possibility, it’s one that I think we as educators should especially bear in mind at all times, not only to avoid an off-putting demeanor that counteracts our goals, but also and more simply to avoid seeming to feign open neutrality while creating an atmosphere of hidden conformity. As Alfred Kinsey taught us about masturbation, D.A.R.E. taught us about recreational drug use, and Donald Trump has now taught us about bigotry, a veneer of socially acceptable agreement will always be the result, to the detriment of real philosophical engagement.

Socrates: “Then we must begin again and ask, What is piety? ….”

Euthyphro: “Another time, Socrates; for I am in a hurry, and must go now.”

Anyway, today I’m not optimistic. Ask me again tomorrow.

I suggest you so-called philosophers listen to this philosopher for once: https://www.youtube.com/user/stefbot

Cheers, and a happy 4 years!

I agree with your points Justin, we do have work to do and those are useful suggestions for us to do that job.

However, I second Arthur Greeves in that we also need to spread, especially among “intellectuals” a different attitude, not the “we knowledgeable people must better teach the ignorant.” but something on the line of a ‘charity principle’ that we so well apply to Heidegger but not to our neighbour. We need to listen more and better.

I’ve found, among those “good people” who vote for bigots and racists, that they too have cognitive aspirations to true beliefs, to sound arguments, to a generally inclusive, charitable and pluralistic world; but they struggle (we also struggle and also make mistakes, though we feel more confident about them) to make order in their heads about all this things: they mix what is desirable with what is attainable, they mix liking a polititician (liking his style, his words, his attitude, etc.) with the content of his policy or the means of acheaving it. These are understandable mistakes, made often by well intentioned people. I’m talking about people, to make an example, who have dear gay friends but resent what they feel as the gay-zation of culture, or who like foreign countries, visit them, befriend foreigners, but feel attacked by cultures that don’t understand.

We have to teach better, to spread philosophy and critical thinking better (as you in this blog so well do) but we also need to be able to really empathize, not only cognitively listen, the concerns of the broad population.

Cheers!

I mean, this all just strikes me as such a straw man. Liberal academics had a preferred candidate–whom they promoted whole-heartedly and sanctimoniously–and she ultimately lost by a significant (EC) margin. There’s sort of two ways of diagnosing the “problem”. One diagnosis is that the *country* got it wrong, and we/it should all feel depressed, shamed, etc. The other is that *liberal academics* have it wrong, and there are two very pertinent bases for this claim.

First, they’re just not representative of our electorate. It’s like me going to an ice cream store that only sells chocolate and vanilla, then I go around grumping about why they don’t have strawberry. Because it’s just not the what (most) people want. So it’s not the ice cream store that’s broken, it’s the preferences that don’t track what the world wants. Of course I don’t expect that liberal academics will admit that they *might* be wrong because that would be too compromising of their self-identity and righteousness.

Second, suppose that the reply is that this should be a more normative argument: the problem isn’t that people wanted chocolate, it’s that they should have wanted strawberry, despite that they didn’t. But then the problem is that the liberal academics haven’t made a sufficiently strong case to anyone, or at least to the electorate. They’re too busy mucking about in their own echo chamber, and their (stipulatively correct) political ideologies just haven’t gained purchase. This is still their failing for not being convincing.

Regardless, so much of the analysis here is that America fucked up. Maybe America did just fine and either liberal academics are fucked up in their views or fucked up by not convincing anyone of those views’ self-evidence. Maybe the conversation and discourse here should be inward looking rather than outward looking. It’s further ironic that a liberalism that espouses universal equality and dignity suddenly becomes schizophrenic when, say, uneducated white men show up in huge numbers and tip the electoral outcome. So what: they’re citizens, and have equal franchise. You don’t denigrate an outcome because the demographic that tilted it isn’t yours.

Jon, it seems like you’re saying either that the majority chose well or that, if they didn’t choose well, it was because academics didn’t convince the electorate to choose otherwise. Is that a correct read? And if so, doesn’t that seem like a small and arbitrary and kind of odd set of explanations to choose from?

Generally, I don’t quite get what is so objectionable about criticizing a majoritarian outcome.

Also, when you write, “maybe America did just fine,” are you saying “in my view America did just fine”?

Heya Justin. I think that liberal academics instantiate a particularly pernicious anti-majoritarianism. It’s not just they have a set of views that didn’t carry the Tuesday, it’s that they (often) think that everyone who disagrees with them is evil or stupid. Call this something like the moral certitude thesis. I didn’t vote for HRC, but I respect and appreciate (many of) the people who did, and I respect and appreciate their hopes for the future of the country, even if they’re not mine. These are (mostly) not evil or stupid people.

By contrast, anyone who voted for DJT is, per the SJWs, irredeemably racist and misogynistic. And even that codifies a fallacy. Say candidate T is for X, Y, and Z, and say candidate C is for ~X, ~Y, and ~Z. If I pick T, it hardly means I support X (e.g., racist comments). Y here could be something like Supreme Court appointments, Z could be anti-oligarchy/establishment sentiments, and so on. I’m not a racist misogynist. Maybe I’m not even pro-Trump, so much as anti-Clinton (e.g., they’re both awful).

I mean, blogs to the contrary, it’s not like only four philosophers voted for Trump, it’s not like all Republicans are repugnant, etc. It’s complicated. But I think liberal academics do themselves and the community a disservice by not being more charitable or thoughtful, or by mucking about in their own echo chambers. And I think they’re too quick to post “please don’t do this to my 3-year old daughter” on Facebook than to try to respect views that aren’t their own. I’d also like to see more say “welp, guess I lost, but hope he does well”–as I did my best to do the past two presidential elections–than to rip the incoming president before he gets started.

I would have thought that one thing people from all over the political spectrum would agree on is that the majority can vote for the wrong person. I agree that liberal academics should get out of the echo chamber and engage people more. As for demographics, Trump won a lower percentage of the white vote than Romney did. This wasn’t a case of “huge numbers” of white voters deciding an election.

I am curious about the claim that Trump supporters are not irrational and/or ignorant. Here in Western PA, it seems many supported Trump because he promised to bring back jobs in the coal and steel industries. If the claim is that their support was rational because he actually paid attention to their concerns, while Clinton did not, then I can accept that their support was rational.

However, if their support was based on the belief that he could actually deliver on this promise, I would suggest that their support was ignorant/irrational, because a) it’s likely the laws of economics make this impossible and b) Trump has not shown much evidence of actually caring about the working class in his actions (i.e., apart from campaign rhetoric). I don’t think people who support Trump for this reason are deplorable or morally objectionable, but it’s hard for me not to conclude that they’re ignorant.

That bit about lack of respect for expertise is funny. The experts were the ones saying Trump would never win. Good luck getting Trump supporters to respect the experts now.

By even the most charitable metric, equating all forms of expertise and treating “the experts” as an undifferentiated, monolithic category is absurd.

This is brilliant. A blog post masquerading as introspection which is in fact just a double-down on unfounded claims of epistemic superiority. As a political opponent, I say: carry on.

I’m not seeing your point. Surely everyone thinks that they know better than those they think voted the wrong way.

I agree with previous comments claiming that this election showed backlash against PC culture and its effect on academia and other institutions where I think the establishment has become univocally liberal, such as comedy shows (which may not be elite, but which millions of people watch). There seemed to be a “boy who cried wolf” phenomenon regarding the instant, full, and permanent demonization of people who violated PC norms or held conservative or religious values. Seth MacFarlane mentions this at https://twitter.com/SethMacFarlane/status/796306781542592512 and Bill Maher expresses similar sentiments regarding previous Republican nominees https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_ul2OuvPOQE

People like Elaine Huguenin, Brendan Eich, and Dan Cathy have been instantly, widely, and for the remainder of their public lives permanently, cast as bigots in recent years, and maybe you still think that they are to varying degrees. But a lot of people felt social pressure to agree with that assessment, kept quiet with their hesitancy to fully endorse that assessment, or felt uneasy about the mountain of vitriol and negative consequences that they faced (in Eich’s case, being essentially forced out of a company he founded and was CEO at, and being called Eichmann for a $1,000 private donation that became public). By the time someone like Trump came around, who has said and done the things that he has (which seem different than those three, perhaps qualitatively) and is running for the highest office in the land, a lot of people had become inured to words like bigot, intolerant, and monster — and frankly fed up with their ubiquitous application. In this election, they responded.

I’ll offer my perspective, which is that of a former student (B.A. in 2011) who tries to keep up with research, general trends, and news about the disciple while also navigating the drudgery of corporate work. I eschewed graduate school due to (at the time) a poor ROI and the prospect of landing a job at a community college in the middle-of-nowhere (more on that below).

My biggest concern is the need for everyone to have the opportunity to develop sharper critical thinking skills. It makes no difference to me whether one is a college graduate, college drop-out, high school graduate or drop-out, professional academic, CEO, corporate drone, or car mechanic – everyone needs to be given opportunities to improve how they select and prioritize information, evaluate that information, develop a worldview on topics or candidates or parties (preferably all), and communicate that worldview with others in polite and constructive debate. It’s harder to survive out here without it.

My professors were pushing for the adoption of the department’s critical thinking courses into the university’s core curriculum, but to not avail. (I’m not sure if that is a standard core class for other public two and four-year universities – Ivy as well). As a student studying philosophy at the time, I thought this was a great idea. Now having been in the real world five years since graduation I think it is imperative. I’ve moved beyond amazement and into a sort of “despair” (strong word) at how poorly most people can handle polite and organized discourse, let alone communicate their ignorantly and poorly constructed arguments. My experience has led me to the belief that the adoption of such courses into college core curriculum and in the public school system at the middle and/or high school level is a societal need. (I’m from a broken working class family and was educated in a sub-standard public school system, so it wasn’t until after I worked to pay/attend college on my own and later ‘stood on the mountains of philosophical rumination’ that I recognized the ‘swamp’ form where I came. Now it feels like I’m back in the swamp, and that I am only one of a handful of people who recognize that we’re in the swamp).

I am curious to hear and help develop ideas of what professional philosophers/academics can do/think they can do in their communities and public school systems (outside of their daily academic environments and responsibilities) to help the current and future electorate sharpen their, as one of my professors liked to say, “critical kung fu skills of the mind.” In my view, critical thinking skills are superpowers which aid their user in detecting bullshit, regardless its origin. I agree on the importance of understanding the views of others and I work hard to put that into practice, but I also think there is a very strong need to help others fine-tune the way they think. I don’t think the point of doing so should be to ensure we all arrive at the same conclusion (though that usually makes things a bit easier). I think the point is to help us create a comfortable and public space for constructing and debating well-thought arguments and ideas. (I hear there are hidden places on the Internet for this…)

In light of my experience post-college, I am giving considerable thought to the idea of completing graduate work with the goal of doing exactly what I wanted to avoid in the first place – teaching introductory and critical thinking courses at community colleges. I have been told the need for such programs may be better addressed at the community college level for now since philosophy/critical thinking courses in public school systems is quite rare and the financial strain on the public education system will continue to place priority status with STEM.

Does anyone on the thread have experience in developing or participating in such programs, writing on the topic, teaching at community colleges or in public school systems, etc.? Any ideas? (I may have missed this in the thread?)

I appreciate the spirit of this post and the suggestions it makes, and it’s good to keep motivating people to think about these issues and do this kind of work. We should also remember that people already *are* doing this work, and may be very good at it, but very likely their efforts are unrewarded or, worse, actively penalized by the institution in which they work. I wish I had appreciated this sooner, as I watched excellent teachers who focus on just this kind of work fail to get tenure, or constantly have to defend their work against claims that it’s ‘not really philosophy’, or be relegated to second-class ‘teaching-track’ or ‘public scholarship’ status, or be pushed toward administrative positions where they felt freer to do socially engaged critical thinking than at the center of our discipline. I don’t want debate the merits of what our profession values, but I want to remind us that in our own departments and cohorts, there’s very likely someone who has been doing this work for a long while now. We ought to be supporting that person, respecting and standing up for their work, and learning from their experience, even as we gear up to refocus our own efforts at this late hour.

Please do not excuse yourself from your complicity in Trump’s ascension to the White House. If your department and university are not diverse, you have helped put him there. Don’t deceive yourself. You are upholding ableism, racism, sexism, xenophobia in the spheres in which you conduct your daily life. Practices on the micro-level of societies make possible more systemic forms of social power.

If your department does not include (among others) disabled philosophers, black philosophers and philosophers of colour, LGBTQ philosophers, and women philosophers (groups which are not mutually exclusive), and you aren’t doing something serious to change that state of affairs, you have helped reproduce an environment that made his presidency possible, even if you didn’t vote for him.

Dr. Tremain,

While feelings of pain, resentment, fear, etc. are completely understandable, I can’t for the life of me understand the purpose of your comment.

Is it really your contention that individual faculty, who do not have ultimate hiring decision-making authority in their departments, are responsible for the makeup of department? And that, if their departments were more diverse,, that Trump would not have won, despite the fact that the bedrock of his support (non-college educated folks) have never set foot on campus, let alone a philosophy classroom? And that more diverse philosophy faculty would, by virtue simply of being more diverse, cause potential Trump supporters to be supporters of Hlllary? And that the ability to influence department makeup is the chief influence that philosophy faculty have (as opposed to, say, their discussions with students in class, or a whole host of other activities not even associated with their profession)?

Frankly, your comment looks a lot like “I’m angry, and I want’ to blame somebody” – despite the fact that those you want to blame had no real impact on the outcome of the election – no impact that is, other than making is less likely that Trump would be the winner. It also looks like an attempt to use the Trump victory as a cynical tool to manipulate faculty into supporting diversity initiatives in hiring (initiatives whose value doesn’t need enhancing by the Trump victory).

Such comments don’t seem to help things at all.

On an alternative reading, perhaps Dr. Tremain was making a suggestion along the “Think Globally, Act Locally” idea?

As a recent grad leaving the world of academic philosophy, who would like to perhaps return in the future but at present has reservations, this thread is really disheartening.

I really thought that if good, constructive discussion about what philosophers and philosophy departments could be doing in response to this and to related events recently were happening somewhere, it could be here.

There are good points made – e.g. the overlooked work of many fantastic teachers already doing what needs to be done; the need to act as facilitators of discussion and not just defenders of non-/experts; the need to really act on making philosophical activity inclusive; the overall need for, and considerable shaking-up of how, philosophers engage with wider society. But even these good points for starting constructive work seem to be drifting in an atmosphere starved of a real sense of community.

I know I shouldn’t take the lack of community feeling here as representative of philosophers’ views of one another generally rn, but it’s hard to resist that feeling.

Hi ajkreider,

Thanks for your response to my comment. I apologize if my remarks seemed obscure in some way. I wanted to suggest (and did) that even if given philosophers did not vote for Trump, they may have contributed to a social environment in which his election was possible. My doing so struck you as implausible and manipulative, though Mohan Matthen seemed to make a similar, and even broader, claim at the outset of the thread that went unchallenged by you.

In your comment, you asserted that “the bedrock of [Trump’s] support [was] non-college educated folks [who] have never set foot on campus, let alone a philosophy classroom”. As I read the exit polls, 54% of white college-graduate men voted for Trump; 49% of white college graduates overall voted for Trump; 48% of voters who earn 250K (many of whom are presumably college educated) voted for Trump. I bet many of these people have taken philosophy courses in what remains a very homogeneous discipline, in very homogeneous universities.

I don’t think that I suggested that department composition is the “chief” influence that faculty philosophy have. Nevertheless, you pointed out that philosophy faculty have other avenues of influence, such as classroom discussions. While I agree with you on this point, I do want to claim that department and university composition will very likely have a significant influence on what gets said in those classroom discussions, what gets said in discussions on social media by philosophy faculty, etc. For example, disabled philosophers constitute about 2% of philosophy faculty in North America; disabled academics constitute about 4% of faculty across the North American university, despite the fact that disabled people constitute about 20% of the North American population. Did nondisabled philosophers discuss with their students the impact that Trump’s policies will have on disabled people? Do they even know? Are they talking to their students now about the impact that Trump’s presidency is likely to have on disabled Americans? I wager that few of them did and that few of them are doing so now. I notice that no contributor to the “Philosophers on the 2016 U.S. Election” directly addressed what is in store for disabled Americans, though disabled people were mentioned in passing in a couple of the contributions. To mitigate this lacuna, here are links to a couple of articles that give an impression of what disabled people expect and fear:

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/disability-rights-donald-trump_us_582487fae4b0e80b02cefa2f (this article uses the same photo as an earlier article, but is indeed post-election)

http://www.vox.com/first-person/2016/11/9/13576712/trump-disability-policy-affordable-care-act

Shelley

We liberal/left-wing academics need to teach conservative/right-wing views and ideas alongside our favored views, present both as compellingly as we can, and criticize both as compellingly as we can. Not only is it educational malpractice to try to inculcate specific views in our students; it is self-defeating. Failure to do so will shore up rural distrust of academia. (I don’t mean to suggest that success in doing so will dispel this distrust, which is, after all, largely based on cynical right-wing propaganda campaigns.)

I suspect that most philosophy teachers already follow this advice. I do have to ask whether this approach is prevalent amongst theorists of gender, in philosophy and other humanities departments. My experience (admittedly limited) is that evolutionary psychological evidence indicating biological origins of gender roles gets very short shrift by such theorists on the whole. Let me put this point a little differently: those who teach courses related to the contemporary theoretical apparatus surrounding “the patriarchy” need to teach, as compellingly as they can, material that objects to central parts of this apparatus.

Entirely anecdotally, some highly political philosophers, in my experience, don’t require their students to consider arguments against the thesis they are arguing for. The students will argue for a left-wing political conclusion in their papers, and have no idea what reasons might be offered for rejecting that conclusion. This strikes me as reducing philosophy to sophistry.

“Failure to do so will shore up rural distrust of academia.”

Sorry, typo; I meant failure to teach left and right compellingly will do this.

”

We must remember that intelligence is not enough. Intelligence plus character–that is the goal of true education. The complete education gives one not only power of concentration, but worthy objectives upon which to concentrate. The broad education will, therefore, transmit to one not only the accumulated knowledge of the race but also the accumulated experience of social living.

If we are not careful, our colleges will produce a group of close-minded, unscientific, illogical propagandists, consumed with immoral acts. Be careful, “brethren!” Be careful, teachers!” – MLK

Dr. King’s words seem quite prescient. There is no critical thought in this evaluation. This argument is predicated on the supposition voters made the wrong choice. That may be but there is no evaluation of the merits of Trump for the deficiencies of Clinton. There is no consideration of the context in which this decision was made War of the Strategies employed by the candidates. There is also a presumption that the candidates are who they claim to be despite all evidence tending to the contrary. In fact one of the candidates appears to be on record attesting the contrary.

if this is the business of a professional philosopher then ‘I do not want to accuse, I do not want even to accuse the accusers. May looking away be my only form of negation.’

Most discussions in philosophy and politics start off with shared assumptions. By all means, challenging your basic assumptions is a virtue, but every discussion doesn’t have to be about the most basic principles. A political discussion does not, for instance, need to begin with a refutation of academic skepticism, even when the discussion relies on assuming that the external world exists.

Amidst all the negativity, it is worth noting that philosophers are in many ways well suited to making a positive contribution to American politics. We study hard, and if we broaden our studies, are well placed to better understand where Trump supporters are coming from. We discuss politics endlessly–we can’t shut about it it! If we can broaden that conversation, we can share thoughts and ideas with the broader population. If we can break out of the cocoon in which we just converse with one another, we might become a beautiful butterfly.

As teachers, we have a captive audience of young people, not to indoctrinate, but to talk to about politics, including the political issues that are concerning them. As we do, let’s not forget to prominently discuss class and economic equality. Maybe we can even put on more classes liable to attract folks who are concerned by economic inequality.

As writers, we must stop regarding publishing for other philosophers as the only legitimate form of publication. Instead, we need to make ourselves part of the national and international political conversation. What’s more, we need to put less emphasis on preaching to the converted and more on conversing with those who aren’t already in fundamental agreement with us.

There is plenty of work to do and nothing stopping us from doing it if we have the will to. The big question is whether we actually have the will to, or would rather just retreat to our academic echo chamber.