The Right Tool for the Philosophical Job

Do philosophers fail to make use of the tools best-suited to their inquiries? Do they even fail to learn how to use these tools? That’s one of the claims made by Jerry Gaus (University of Arizona) in a rich and wide-ranging interview at 3:AM Magazine. He says:

Making a model more formal allows us to be more precise about what the interesting bits are, and how they are related. It does what philosophers have always excelled at: getting the ideas and their relations as clear as possible. Whether the model should be mathematical depends on the problem. As I constantly preach to my graduate students, we should never be committed to a tool or method and then look around for some problem to apply it to; we should look at the problem and try to see what tools will allow us to achieve insights. Sometimes it will be one that directly employs math, sometimes a simulation will be enlightening, sometimes it would be good to run an experiment, and other times game theory might be useful. They are all tools that might help. The problem is that all-too-many philosophers—certainly in my field, political philosophy—have convinced themselves that models and math cannot be relevant and so they never learned these tools and can’t even see where they might help.

The failure to learn and use such tools is sometimes thought to be unimportant (jokingly: “Oh, I don’t do statistics”) and is sometimes not only overlooked but defended. I’ve heard authors give papers that make various quantitative empirical assertions (“there’s more and more X these days”, “the valuing of Y will lead to less Z”) and when asked for statistical evidence for these claims, reply, in essence, “this is not how my subfield operates.”

The picture is complicated, of course, by disagreement over what philosophical insight into a problem is. But also, “I don’t know how to do that” or “that is not how we do things here” are not themselves defenses against charges of lousy scholarship.

It would be useful to get a sense of what philosophers think the right tools for the jobs are. We can ask: which non-traditionally-philosophical special skills are needed for worthwhile philosophical inquiry into which topics? And also: where are some of those tools misapplied?

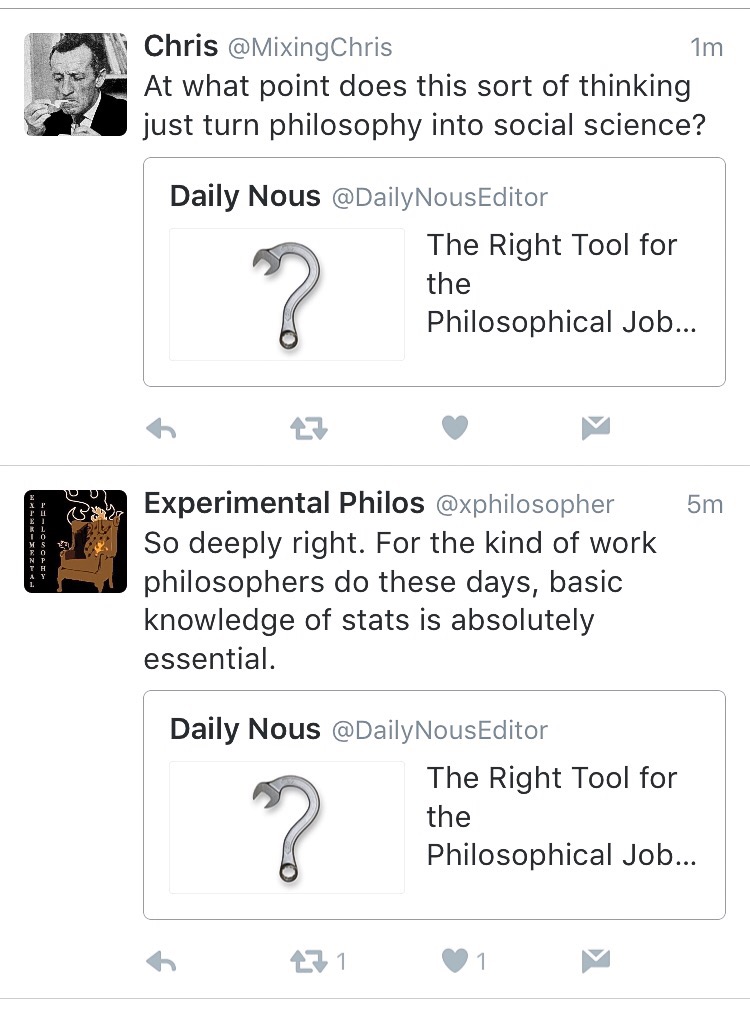

UPDATE: Already some difference of opinion on this:

Unsurprisingly, I completely agree. My sense is that no one is really opposed to the idea of philosophers having more knowledge of statistics. The question is rather a more practical one, about what we should actually do to make this happen.

At Stanford, the philosophy department recently decided to replace the traditional course in “baby logic” with a broader course in “formal methods,” which offers an introduction not only to logic but also to statistics. Given the directions in which philosophical research has been going over the past few decades, this seems like an excellent way of introducing students to the mathematical tools that are most likely to actually prove helpful in their subsequent work.

I’ve always thought of philosophy (and its various sub-fields) as defined in terms of the questions that are asked, rather than the tools that are deployed to try and answer them. It sure seems that through time different kinds of tools are brought to bear to answer the questions – philosophers had to develop some of the tools, after all.

To the degree that we care about policing what counts as philosophy versus science, doesn’t this become remarkably apparent as soon as someone talks to someone from the relevant discipline? They just care about different questions. In my experience, that’s one of the main reasons that truly interdisciplinary work is difficult – people have different core questions that they want to ask that stem from their disciplinary backgrounds.

Set theory is great for some questions. Computer simulations are fantastic. Game theory is really quite useful for getting at some questions. Coming up with a nice thought experiment can be useful. Our tools aren’t equally good at all things. It would be weird if they were. So either you can adopt more tools as you need them, or you let your tool dictate the kinds of questions you pursue.

Now, I think there are two perfectly good research strategies in any field. One is to have a set of questions that you care about, and then as you doggedly pursue those questions, you equip yourself with whatever tools that you might need to go after them (this is what Gaus advocates). The other is to really invest in a particular tool or two, and then just try and find whatever problems you can that the tool gives you an advantage at answering. This sounds more mercenary, but it’s probably a lot more epistemically efficient. Both are perfectly fine ways of doing philosophy (or science). What is (in my mind) a bad way of doing philosophy is to only use one tool, and fail to realize that it can limit you in important ways. Tools aren’t neutral. They shape how we think about problems.

“[…]it’s probably a lot more epistemically efficient.”

Perhaps a small point, but Just to push against this: starting from the tool presupposes no knowledge of which problems might appropriately be addressed by the specific parameters of the tool (even if we restrict ourselves to a given sub-field.) Searching in this way, even with some guidance (ex. I know that this problem requires some tool like a wrench or a screwdriver or…) seems likes a poor strategy, still a bit like groping in the dark, and so less epistemically efficient, while also running the risk of producing bad philosophy (that which is to be avoided in this context: formal methods applied to problems for their own sake), unless we are presupposing a panoramic understanding of all that could be interestingly modeled in every philosophical approach to every problem in the domain (or perhaps some great number of them), in which case it would indeed be more efficient to start from models and see what matches. Perhaps an expert in a given area who is already familiar with many approaches to a set of problems might examine some formal tools to see if they can apply, but then it is hard not to see her selecting tools in the other direction, with a sense already of what specific parameters are interesting and so of what tools should be appropriate and potentially illuminating.

Both approaches I suggest require some amount of knowledge of the other side. Being an expert in some tools requires knowing a bit about what problems are around, and being an expert on a question requires some knowledge of the tools available to address it. Both approaches can easily generate bad philosophy because it is pretty easy to generate bad philosophy. Importantly, what tools you have at your disposal shape how you see problems (and shape what problems you see). For the tool-first approach this can allow for some great unification of problems – look at how useful evolutionary theory has been across disciplines, for example. This approach can be more efficient insofar as it is quite costly to master a tool (whether or not it is a formal tool).

On my website I have some papers on the division of cognitive labor in science where I more carefully go through these options.

Provided that you have some knowledge of the problems, and some contact with colleagues that can tell you more about the ones you don’t know, I don’t see why starting with the tool and then looking for the problems would be worse off than starting with the problems and looking for the tools would be. After all, this is what most people in most professions do! In a well-functioning economy, an auto mechanic doesn’t need to go around looking very hard for a problem that needs auto mechanic skills – those problems come looking for her! Similarly, if a philosopher is known to be particularly skilled at working out formal models of social epistemology, or at doing detailed phenomenological descriptions of mental states, or whatever, then people who have a problem that seems to be amenable to those approaches should be able to collaborate with them.

So I think, with quite a few other philosophers, that a working knowledge of social issues and cultural history is deeply important for “the kind of work that philosophers do these days.” We write about concepts that have histories, we defend ethical ideas which are socially and historically contested, we deploy metaphysical intuitions which depend vitally on our inhabiting a certain social and historical context… I could go on and on. Gaus’s own work shows how fantastic philosophy can be when it is supplemented with this sort of awareness. Yet, is anyone deploying this engineering-speak (concerning “tools” and “jobs”) to attack the lack of this sort of knowledge amongst philosophers, or its near-invisibility in contemporary debates? No. That alone makes this argument suspicious. I want to know why it is automatically directed against a perceived lack of mathiness but not directed against a great deal of other intellectual or professional failings which demonstrably hinder us. Unfortunately, I think that the psychological mechanisms at work here are depressingly familiar, but I’ll let the reader draw their own conclusions.

I agree with everything you say here about the importance of social history for philosophy. I am puzzled, however, about why you would see the view being proposed here as in any way in tension with yours.

This view being proposed here is that it would be good for philosophers to be acquainted with a wider variety of different kinds of mathematics. Clearly, that view is not incompatible with the claim that it would be good for philosophers to know more about social history. On the contrary, my sense is that there is a positive correlation between the two. That is, there seems to be a slight correlation such that the more a philosopher believes that it would be good to know about a wide variety of different kinds of mathematics (rather than focusing on just one specific kind) , the more this philosopher will tend to believe that it is important to know about social history.

“Social issues and cultural history” do not equal “social history.” Interestingly, the latter is characterized by… statistical and other “mathy” methods. A revealing slip?

My apologies. In any case, I am right now co-authoring a paper with a faculty member in the history department, and the kind of history we are drawing on is not at all quantitative but very much in the humanities tradition.

More generally, I think it is a mistake to see any kind of antagonism between the idea being proposed here and the idea that philosophers should be more engaged with historical questions. The idea being proposed here is that philosophers should be interested in a wide variety of different mathematics tools (rather than focusing almost entirely on a more narrow range of mathematical tools). This idea seems very much in the same spirit as the suggestion that philosophers should be interested in a broader range of work in the humanities.

My AOS is the philosophy of physics. Mathematics and physics are both useful to know in doing research in this area. However, it’s also important to have excellent philosophical abilities: to distinguish closely related but often conflated notions; to evaluate whether an author has provided adequate reasons to believe his or her conclusion. Particular philosophical knowledge is also useful, in metaphysics and epistemology, for example.

Perhaps a variant on your second question is: How often do philosophers of physics write poor papers due to lack of development of philosophical abilities or substantive philosphical knoweldge, despite great mathematical and physical sophistication? In my experience, there seems to be quite a difference of opinion among practitioners on this issue.

I think that there are a couple of issues raised in the OP that are worth distinguishing. One is learning how to better use mathematical models. The other is paying proper attention to statistical evidence in ways that don’t necessarily require more than eighth-grade mathematical education. Obviously, the two are related and the better we understand mathematical models, the less likely we are to make errors interpreting statistics. However, it seems to me that the most important problem is inattention to statistical evidence rather than a lack of mathematical understanding.

If philosophers train for anything it should be for reasoning well no matter what the subject matter. Now I get that “reasoning” is a house of many mansions, but the common foundation for all those mansions is built of the formal methods of both deductive and inductive reasoning, and I’d think that no philosopher worth that title shouldn’t be pretty familiar with the foundations of these forms of reasoning, especially after their equally powerful developments in the 20th century.

If you’re making empirical claims, you should know how to back them up with whatever tools, mathematical or otherwise, necessary. However I’d be inclined to think that there’s a great deal of political philosophy that is dealing with concerns of a more a priori type: ethical, etc. These would not be helped by appeals to mathematics, and it is arguable that a lot of the empirical concerns in political philosophy would be better farmed out to economists and political science people, although of course there’s a great deal of continuity there.

There are other examples, for instance where do intuitions play a role in metaphysics, etc?

“However I’d be inclined to think that there’s a great deal of political philosophy that is dealing with concerns of a more a priori type: ethical, etc. These would not be helped by appeals to mathematics”

Why not? Is mathematics not *a priori* enough?

When was the last time mathematics solved an ethical problem?

As a general; rule I find philosophers who are decent mathematicians to be ‘more rewarding than those who are not. This is not for their mathematical skills as much as for their mathematical attitude, which seems more rigorous, dispassionate, honest, fearless and above all ruthless than those with a more ‘arty’ approach. Many philosophers seem reluctant to be as businesslike as mathematicians. .