Talking Philosophy With Your Kids

Philosopher parents: how, if at all, do you talk philosophy with you own children?

I don’t give my children philosophy lessons, nor do we celebrate Socrates’ birthday. There may be a few more books of logic puzzles laying around the house than average, along with many of the children’s books listed here, but I don’t force philosophy on the kids. If the opportunity to turn a conversation towards philosophical questions arises, I occasionally take it, just to ask a few probing questions or to explore a couple of ideas, but I find that most of my attempts don’t go far. It’s better when they’re the ones to start the conversations, as when my oldest son came home from school one day in first grade and reported on his lunchtime conversation with the janitor over the existence of god. Or when, more recently, my daughter, in the latest in a series of uncontrollable fits of laughter, caught enough breath to quickly ask, “Why is this funny?”

I’m not particularly interested in turning my children into philosophers. But I do want them to appreciate philosophical inquiry. I imagine that many other philosopher-parents feel the same. What is your approach?

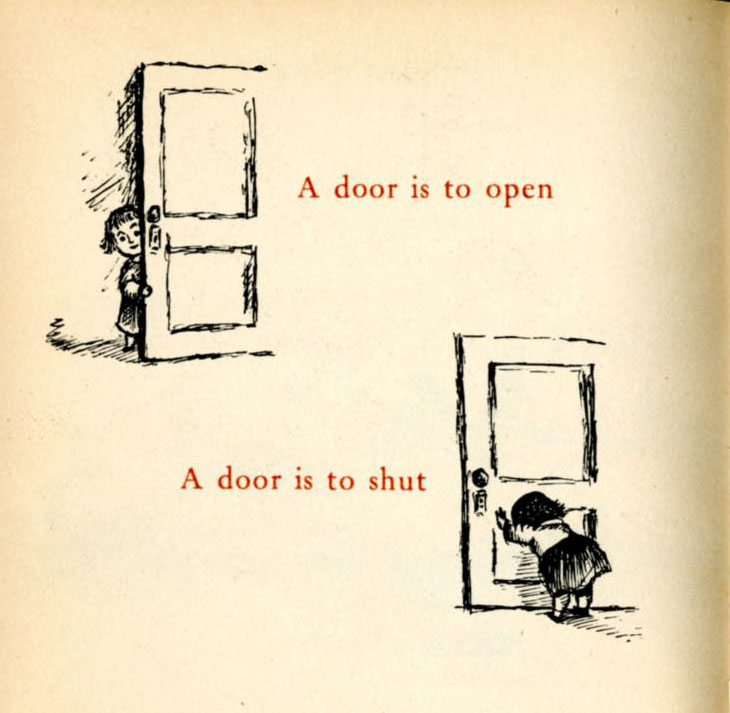

(from A Hole Is To Dig by Ruth Krauss and Maurice Sendak)

How do I talk about philosophy with my kid (she’s four)? ALL THE TIME. Over the course of this weekend alone, she asked me “What is nothing?” “What is belief?” and “What is friction?” (OK, so that was physics rather than philosophy), plus the outraged assertion “Persons are not animals!!”

We talk about philosophy — or rather, philosophical topics — all the time, because I don’t know any other way to help her develop her conception of the world. When she asks me a question, it’s not uncommon that I’ll respond “are you asking for an epistemic or an ontological [x]?” She may not entirely understand what these words mean, but she’ll learn.

Whenever she asks me a question, I always aim to tell her true things (unless, of course, the question is “where did you get that chocolate bar?” in which case lying is completely warranted because it’s Mommy’s chocolate, and she doesn’t need to know where I have it squirreled away). Philosophy at its best is the pursuit of truth, so why wouldn’t our conversations every single day interact with philosophy and philosophical method?

if they misbehave I send them to their Chinese Room for the rest of the evening

But does that really help them understand what they’ve done wrong?

I discussed a version of the trolley problem with my five-year old. It didn’t involve anyone being killed, just different groups of people being bumped by a runway tricycle. And she thought it was fine to steer it into a smaller group, but not to push someone in front of it. Seemed pretty good intuitions to me.

Before that we had a long discussion about what she would do with an invisibility ring. And we often talk about which rules you have to follow because they are rules, and which things you just have to do, whether someone tells you or not.

Part of doing philosophy with children is listening to them and asking questions about their ideas instead of correcting them or giving them the answers if the situation (and your patience) allows for it.

My kid, now 10, has 2 philosophers for parents (“poor thing,” my students say). We both value philosophical and scientific reasoning, but also art and nature. We admit when we don’t know the answer to some questions she asks, and we explore possibilities with her trying to make connections with other things she knows. At some time or another, she has entertained a number of the popular thought experiments. She recently offered to illustrate Inverted Earth for me for a presentation I will be doing.

The effect all of this has on her dispositions is most apparent to me when we are around other kids her age who sometimes jump to conclusions, make bizarre assertions, or parrot back what adults have told them. My daughter rolls her eyes or raises her eyebrows (she learned that from me) as if to say, “Can you believe this guy?”

When she was about 4 or 5, my logic students had been complaining that learning the valid argument forms was too hard. I taught my daughter modus ponens and modus tollens and wrote a handful of problems on the whiteboard for her to solve. I made a video of her quickly solving them and then showed it to my poor students. So much for their fragile egos.

What has she learned from all of this? She wants to be an art teacher and she covets office supplies.

It depends on what you mean by “talk philosophy with your children.” If it means “talk about philosophy” with my children, then I don’t think I have ever done this with my children (who are both under the age of six), and I don’t think I will do this for many years to come. (Depending on the day, when they ask me about my job I tell them “I’m a teacher” or “I’m Superman’s sidekick.”) But if it means “do philosophy” or “philosophize” with my children, then I think I have been doing this nearly every day since my kids were three or so by making distinctions with them and by helping them to find the right words for things and feelings. Last night we were reading a book about animals, for example, and I asked them, “Don’t you think cheetahs and tigers are pretty much the same thing? Come to think of it, I’m not sure I can find any differences between them. Can you?” And they were off, naming all the differences they could find based on the pictures and what we had just read. Later on, one of my kids said he was “really scared of the dentist.” I asked him whether he was scared of the dentist or nervous about going to the dentist. That led to a neat conversation about the differences between fear and nervousness (it also got his mind off the dentist). Maybe none of this is technically philosophy, but I think discussions like these will turn my kids into good philosophers later on.

We discuss things philosphically with our kids (who have two philosophers parents), but don’t bring up specifically philosophical terminology or traditional topics with them on a regular basis. There is a lot of us discussing philosophy in front of them, such as at the dinner table, but it is hard to tell how much of that gets soaked up by them. Our daughter is either paying acute attention but saying nothing, or really good at ignoring us without looking rude.

I philosophize with my 6-year-old daughter virtually daily. When she makes assertions, I ask her to explain why, and help her think about better and poorer reasons and explanations. Likewise, I encourage her to challenge me, to make me explain why I do or don’t let her do something. Her arguments have (sometimes, far from always) induced me to change my mind. She has an acute sense of fairness and justice, even if her understanding of these ideas is still developing. And she’s gaining a much larger passive vocabulary and an appreciation for how much fun it can be to play with language. (Sometimes, her own language games have sent me to rethinking Wittgenstein’s take on private language, etc.)

My daughter loves science so I bring up philosophical topics in scientific ways. For example, do you know about absolute zero? Why do you think there is an absolute zero but heat is infinite?

If only 7% of the universe is detectible by human beings. how can some people be so certain in their beliefs? … That leads to critical thinking. She got into an argument with her science teacher who is a devout Christian. S he called her ridiculous!