Should Professional Philosophy Be More Like Grad School?

Graduate student Nick Byrd (Florida State) sends in an interesting thought to ponder: maybe professional philosophy would be improved in certain respects if it were more like graduate school. He writes:

If grad students were paid better, I’d be a serial PhD student. Grad school seems more fun than many of the post-grad experiences I hear about. Now I am beginning to wonder how professional philosophy might benefit from borrowing elements of the grad school model. E.g.:

- What if professional philosophers were required to assist or co-teach a certain number of their colleagues’ courses (modeled after teaching assistantships)?

- What if professional philosophers were required to formally assist a certain number of department colleagues’ research (modeled after research assistantships)?

- What if adjuncts (and some SLAC faculty) were paid as generously as most grad students? (I get an adequate stipend + tuition + benefits + conference reimbursements; I see lots of adjunct positions that don’t compensate nearly this well.)

I suppose there are already professional equivalents (or quasi-equivalents) of many grad school requirements (e.g., qualifying papers a la evaluating publication record for tenure review, etc.), but maybe there are other opportunities that I am overlooking.

One “easy” response to these proposals (especially 1 and 2) is to object to how fanciful they are (e.g., “who would have the time for that?”) but the idea is to consider what it would be like if academia were restructured in such a way as to make them normal elements of professional life.

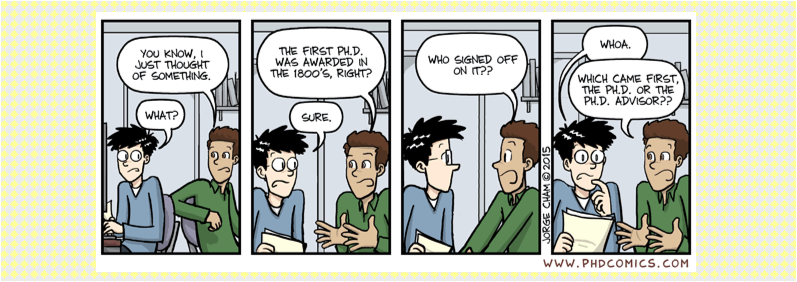

(image: PhD Comics, 5/22/15 by Jorge Cham)

I don’t think we should think of 1 as fanciful. When I was an undergraduate, it seemed to be more common for faculty to lead discussion sections in courses other than their own. (I could be misremembering this – maybe someone from Monash can tell me if I’m totally wrong about how discussion sections/tutorials work there.)

And as an undergraduate, this seemed like a great result. A discussion section led by the course lecturer doesn’t have quite the same new spin on the material that I think the best discussion sections can help provide. But it also meant that you got to interact with senior faculty on a small scale setting. If a pair of faculty simply swapped discussion sections – each leading a section in the others’ lecture class – we’d get some of the advantages of Nick’s plan, and possibly a pedagogical improvement too, without a huge increase in time faculty spent.

I am very much in favor of faculty voluntarily cooperating as outlined in suggestions 1 and 2. I do not think that 1 and 2 should be requirements, however. Faculty need flexibility to pursue their work in the way they think is best.

As for improving wages and conditions for adjuncts, it is a moral imperative.

HNM has it right, I think. Too many people (including many with whom I’m otherwise in 80-99% agreement) seem to have trouble with the concept that “Would it be a good thing if more people did X?” and “Should X be mandatory?” are not, in fact, interchangeable. I mean, if you directly asked “are these two questions the same?” I’m pretty sure hardly anyone would say “yes”, but in practice, far too many people unthinkingly frame issues as though they were. I think it would probably be good if these were widely accepted cultural norms, but very bad if they were rules university bureaucracies had the power to enforce.

1. I wish that my university did not count team-taught courses as only fulfilling one-half of a course for the purposes of my teaching load. Anyone who has team-taught in the past (where ‘team-teaching’ means both instructors are in the room together and not merely where they tag-team a class by alternating lectures) knows that they are just in much work, sometimes more (in terms of prep-time) than solo-taught courses.

2. I wish that my university did not count co-authored articles as one-half of an article for the purposes of tenure and promotion. For the increasingly lucky few who have the luxury of worrying about achieving tenure, the pressure to publish solo-articles due to this kind of discounting is much too large to ignore.*

3. HNM is right. This is a moral imperative. To ignore this is to engage in bad faith. To fail to advocate (when one is in the position to do so: ) is to fail one’s duties.

*This is not to imply that non-tenure-track labor lacks the pressure to publish. In many ways the pressure to publish is even greater for NTT labor (though different). Given the short-term and insecure nature of most NTT labor contracts, it is even more difficult to form the kinds of relationships that can lead to co-authored works in the first place.

I wonder how common this is. Those rules are, obviously, strong disincentives to 1 and 2. I wonder if making 1 and 2 more common could be as simple as removing/revising these sorts of rules, or if it would take more than that.

Team taught courses count as full courses for the purposes of teaching load in my department. Predictably, this results in more team-taught courses. This seems, all things considered, to be a good thing. No faculty acts as a “TA” for another faculty member, though, and I wonder what would be gained from a model closer to that, other than perhaps an unnecessary and uncomfortable further entrenching of existing hierarchical structures within departments.

While I’m not sure I would put a quantitative measure on it (i.e. “one half” or “one”), co-authored papers are also quite the norm in my department and considered just as important as solo-authored papers. Predictably, this results in a great deal more collaboration. I should note that this is the intended effect: faculty here are not only encouraged, but quite expected to collaborate with other faculty both within the department and outside of it. So in this sense, something akin to (2) (although not quite the same – I don’t believe anyone here is acting like an RA for our colleagues) is very nearly a requirement for success in tenure applications. This also seems, all things considered, to be a good thing.

Grad school probably is more fun than most post-graduate experiences. But it’s not because you get to lead discussion sections for someone else’s lecture class. It’s because (I think) you spend more time on philosophy and less on teaching and administration. Plus you’ve almost certainly got a peer group of people your own age with similar interests close at hand, which presents more opportunities for socializing than you may have once you’re out working.

No. 1 isn’t very fanciful. It’s how many (a majority?) of courses are done at Durham. Last year I co-taught a 3rd year Language & Mind course with two others, this year I’m co-teaching a 2nd year Logic, Language, & Metaphysics course with one other.

Brian remembers right — Monash faculty definitely did lead sections of other professors’ classes. I taught a section of Aubrey Townsend’s logic class, and I learned a few things that came in handy later, too.

Princeton tenured faculty also lead sections of each others’ courses — “precepts”, they’re called.

When I was an undergrad at MIT in the late 70’s, faculty members, sometimes famous ones, taught the discussion sections for large lecture classed in the sciences.

As several people have pointed out, #3 is a moral imperative.

As to points 1 and 2, that doesn’t reflect my experience of grad school–by the time I was a few years in (this period lasted a while) I was teaching my own courses more often than not, and I only did research assistantships for a couple of terms (which was more than most of my peers). Which makes me think that Dale is right–it’s spending more time and not as much on research and (especially) administration, as well as having a different peer group. Also, the audience for your research is your committee, which is committed to your research somehow, unlike the anonymous reviewers who you’ll be submitting most of your research to later–the reject rate for dissertations is much lower than for papers. And this is as someone with a pretty cushy job, which probably gives me more time to focus on the more fun parts of philosophy.

I experienced mentorship by members of departments at my grad school when I was a grad teacher, and at both schools where I taught after grad school. In addition, I had colleagues who were willing to do all of what is mentioned in the article on an informal basis. It strikes me that compelling or requiring collegiality is not necessary and maybe a negative. I had never, in 35 years of teaching, lacked for collegial support, advice, etc…