Plot Philosophy’s Subfields

Yesterday’s post about interdisciplinary work in philosophy got me curious about how philosophers understand their work in relation to other disciplines.

One question we can ask of academics is: “what do they take themselves to be studying?” Of course, there are various ways of answering this question. One way of doing so is trying to determine where on a spectrum between “things” and “our understanding of things” researchers locate the object of their inquiries. That is, do they tend to understand the object of their inquiries to be first-order knowledge of the world (including us), or do they tend to understand the object of their inquiry to be second-order (or higher) knowledge, that is, knowledge of our understanding of the world? (For example, I take chemistry to fit better with the former, and literary theory to fit better with the latter.)

Another question we can ask of academics is: “by what methods do they seek to acquire knowledge?” Again, there are various ways of answering the question. One way of doing so is trying to determine where on a spectrum between more and less empirical their methods are (with “empirical” here excluding introspection).

It quickly becomes apparent that philosophy is too diverse for there to be easy or uncontroversial answers to these questions when we ask them about what philosophers in general do. However, we might have an easier time asking the questions by subfield (easier; certainly not problem-free). And perhaps doing so will help us better understand the diversity of philosophy as well as philosophy’s relation to other areas of inquiry.

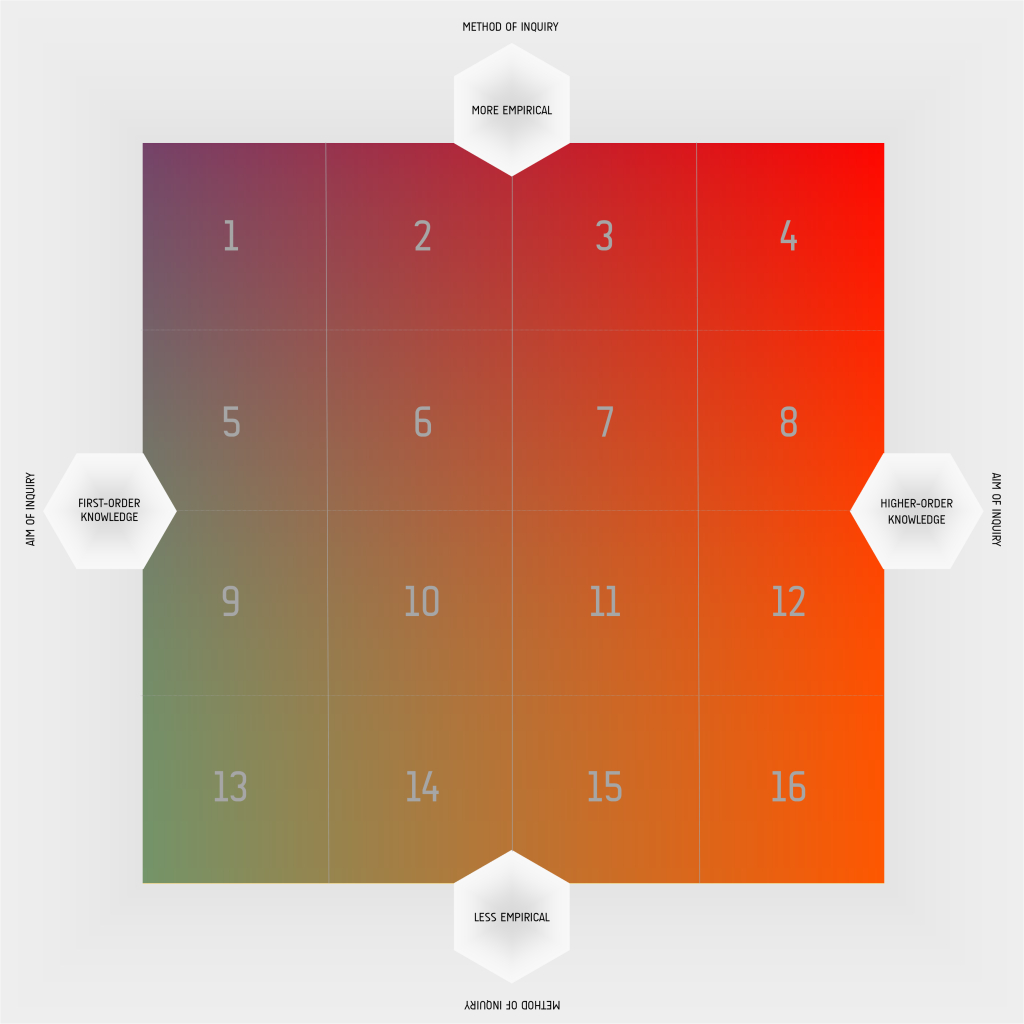

So, to that end, I ask for your help. I used the two above questions to create a matrix. What I’d like to know is where you think various subfields of philosophy best fit on the matrix. Start with your own area of specialization, but feel free to place other areas, too. For ease of answering, I broke the matrix into numbered squares, though the squares should not be taken as marking off cleanly delineated differences. Additionally, the matrix is purposely not fine-grained, as I have no illusions of precision.

Here it is:

To give you a sense of how to answer, here are some sample answers I’d give:

Analytic metaphysics: 13

Deconstructionism: 16

Experimental philosophy: 4

Philosophy of physics: 6

Political philosophy: 10

History of philosophy of science: 8

(I imagine some may disagree with these sample answers; please feel free to register this disagreement and provide alternative placements in the comments.)

Clearly, there are some complications that this matrix ignores (e.g., someone might think that where subfield X belongs on it varies according to one’s substantive views about X). To the extent possible, try to put these aside. I don’t know if this is going to be a fruitful exercise. We’ll see. Comments about that and suggestions are welcome, along with your tagging of various areas of specialization. (If we get enough answers, expect a subsequent post that will include a visualization of the answers.)

Philosophy of psychology/cognitive science exists on both the left and right sides of the spectrum. There’s a way of doing phil psych that makes it a kind of first-order investigation into the structure and content of the mind. On this approach it looks like an empirically informed version of (a certain kind of) philosophy of mind, or what Fodor once called “speculative psychology”. However, there’s also the version that makes it more like applied general philosophy of science: an investigation into the methods, models, and logic of empirical investigation in psychology in which the main concern is the structure of the discipline rather than the mind itself. My work on concepts goes in the former camp, my work on models and mechanisms goes in the latter.

Also, what counts as a subfield? “Deconstructionism” isn’t obviously one; it’s a strategy of reading, or a critical method, not something defined by a particular subject matter, unless it’s “texts in all their manifestations”. But the same might go for (some of) “experimental philosophy”.

I hear you, Dan. I found it difficult to place political philosophy, given the diversity of approaches and subject matter it covers, too. I ended up putting it where I thought the center of gravity on a scatterplot of its various elements would be. Perhaps a better approach is to be more fine-grained. This gets to your question about what counts as a subfield. I purposely did not comment on that, thinking we could learn more by leaving it open ended. Your example suggests that in identifying subfields, people should err on the side of narrowness.

Rather than err on the side of narrowness, it may be more fruitful to consider the possibility that subfields may show up on this matrix as dynamic patterns: loops, flows, maybe even non-linear strange attractors.

My own work in practical ethics and the pedagogy of practical ethics has been looping and gyrating all over this matrix, sometimes attending closely to the empirical work aimed at first-order knowledge of human cognition, sometimes stepping way back to take a critical view – aimed at second-order knowledge – of the study of human moral cognition.

I suspect many of the more practically inclined subfields might move around in a similar fashion.

This is a good point. Maybe we should be asking people to use as many squares as they need, rather than just pick one. But even if we don’t, the results could be represented graphically as loops for each subfield, with the thickness of each loop’s line increasing in those boxes that were the more popular answers for that subfield.

Regarding all the responses (and subresponses) to Dan’s question, I thought that one way of proceeding might trade on distinguishing where a subfield belongs on the matrix from where most practitioners in a subfield belong on the matrix. It seems like matrix placement is highly dependent on one’s methodology, but many subfields can be approached with various methodologies (as others pointed out). Indeed, given that subfields in philosophy don’t really seem to cut at the joints of methodological possibilities, one might think that those subfields that do seem to sort in a given box really only do so because of how we happen to practice them currently. If all that’s right, it might be easier (and operationally easier to define) to think about wher people working in X subfield would take their work in X subfield to fall on the matrix rather than where the subfield belongs.

Think about the very different reactions to the Vienna Circle (and its heirs) that seems prevalent in contemporary phil sci versus contemporary metaphysics. Not long along, it seems to me, those two subfields would’ve been a lot closer in our matrix than they are now. But that seems to be a fact about what people do rather than about the subfield per se.

A different, more personal case (for me). I do a lot of work in applied ethics/political, parts of which (particularly in regard to legitimacy) I think benefit by learning from analogous questions in jurisprudence. But most analytical jurisprudence (after Hart), I think, moves closer to the upper-right-hand corner than what most people who think of themselves as doing bioethics (probably more upper-left-hand) or most people working on normative issues in rights theory (probably more lower-left-hand). Maybe those very fine-grained subfields look like 3, 6, 9, respectively?

Maybe 7, 6, 9 is better, now that I think about it. But I could be argued into all sorts of different sortings.

The difficulty with this suggestion is that my own work in the subfield of practical ethics (sub-subfields environmental ethics and engineering ethics) tends to shift around a lot. One day, I might be reading Piaget’s studies on moral development of children, the next I might be refining a phenomenology of moral experience, the day after that designing an assessment instrument for pedagogical research using models from ethnography, and sometime the following week delving into the metaphysics of morals.

I don’t think I’m the only one whose work shifts around that way. Consider, for example, where Aristotle’s Politics would fit (or not) on the matrix. Sometimes, he’s engaged in the description and comparison of different constitutions, sometimes in argument about how a city ought to be constituted, sometimes in more ground-level prescriptions for public administration and public policy, and sometimes in reflection on the methods of political philosophy. That might involve at least four different sectors on the matrix, maybe more, depending how you plotted it.

Hi Bob,

I think that’s right. (My own work shifts too). I guess I was hoping (though it may be naive if we were to do some empirical work) that clusters would emerge around, not what any one given person worked on, but around what groups of people worked on and how those groups thought of their work. So, while, for instance, my work in bioethics looks really different than a lot of other bioethicists some sort of overlap about how bioethicists tend to think of their methodology might emerge. Of course, there would be outliers, and of course, that’s not to say the outliers aren’t doing interesting work. (I hope not. I might not fit into any cluster as best as I can tell).

Obviously, we’d have to do a little be of mathematical modeling to actually do such work, but this was roughly one way of trying to think about operationalizing what it meant for a “field” to fit into, what seemed to me to be, a matrix composed of methodological divisions.

Will

Where would you put history of philosophy? It seems to be a weird case insofar as one and the same historian of philosophy might have aims which could easily be described as falling on each of the four extremes. For instance, someone might aim to be both historically accurate (empirical?) and to speculate about what a philosopher would have or should have said (less empirical?). Also, many historians care about what these past thinkers thought (higher order knowledge?), as well as about, for instance, whether there is a god or whether pleasure is the only intrinsic good (first-order?).

I would think that history of philosophy would be towards the right side of the matrix, and somewhere towards the vertical center for the reasons you give. So, 8? (–but I’d like to hear what historians think!). As you point out, people who work on history of philosophy often also work on specific philosophical questions; I don’t think this is a difficulty for the exercise, though, as the matrix is for placing the subfields, not its practitioners.

Considering work which aims to understand the actual view of some historical philosopher, I would have put it somewhere in the upper left. It’s empirical, because it’s strongly constrained by historical and textual evidence. It’s about first-order knowledge, because trying to understand Leibniz’ theory of space (for example) is about a specific guy rather than about something general or abstract. Of course, one could use a discussion of Leibniz’ view as an occasion for armchair reflection about space — that would go on the lower right.

Wouldn’t “work which aims to understand the actual view of some historical philosopher” be towards the right, not the left, as it is about figuring out the historical philosopher’s view or understanding of X, rather than about figuring out X itself?

I suspect a great many analytic metaphysicians will disagree. I think lots of metaphysicians these days think of metaphysics as continuous with science/physics/the philosophy of physics, or at least, as being an area of inquiry that needs to be well-informed by those things. Also, everyone tells me that I do analytic metaphysics, but I’d put myself squarely on the right hand side. (Though I don’t think I really get this “first-order”/”higher order” distinction all that well, it seems like a bad distinction to me.)

I also don’t see the point of this exercise and suspect that even the answers of people in various fairly narrow subfields will give answers that are all over the map. I’m not sure what that would show or, more importantly, why we should care. Of course methodology matters and how we conceive of what we are doing matters. But you’re not going to get any useful information about any of that from some chart full of random numbers.

Thanks for your thoughts regarding metaphysics. I don’t think my understanding of where it belongs is particularly idiosyncratic, so learning that many metaphysicians would disagree would be rather informative.

As for the first-order / higher-order distinction — I agree that problems could be raised about it, but I do think it gives enough of a picture of a difference in subject matter. One reason why philosophers doing interdisciplinary work are more likely than others in the humanities to bring into their research a science field (rather than another humanities field), I thought, is that (some? many?) philosophers tend to see what they are doing as closer to the sciences than to other humanities. So I was trying to figure out how philosophy is similar to the sciences and different from, say, the study of literature. One thought that came to mind is that (some? many?) philosophers take themselves to be trying to figure stuff out that is true about the world, like scientists try to do, whereas, say, those who study literature or rhetoric are trying to figure stuff out about, say, our understanding or interpretation of the world as contained in various texts. But since not all philosophers understand their work this way, I thought it would be interesting to look inside philosophy to see how different subjects or questions fit along this spectrum.

Of course it is true that literature and other texts, along with “our understanding of the world” is part of “the world,” at some level of description, and that all philosophers pay attention to other philosophers’ understanding of the world in their work, but I’ve tried to make clear here what I was getting at and why. If you have a better way of crafting the spectrum, I would be glad to hear it.

It may turn out that answers, even for narrowly defined subfields, are all over the map. I would take that to be a very interesting finding about philosophers’ understanding of their work and how it fits in with other subfields and other disciplines. (And as for the numbers — they are there just to make answering easier; one can say, “7” rather than “about two-thirds of the way to the right and about five-eights up from the bottom.”)

As a side note, please be aware that comments like “I don’t see the point of this exercise” and “I don’t see why we should care” often have the effect of discouraging participation, and it is disappointing to see them appear so soon in a discussion thread. Perhaps we can withhold judgment a bit and see what the conversation yields, or more constructively contribute to improving the inquiry. As I said, I am open to suggestions.

Where would you put aesthetics?

I was thinking about both aesthetics and history of philosophy – well, since both somewhat applies to me. I am not the expert on analytic theories of aesthetics, but I guess the historically informed, continental version that I do is at either 11 or 7 (what is the notion of intersubjectivity in 18thC aesthetics?). Aesthetics needs some empirical input, if we take the notion of the artwork as having a necessary physical residue seriously (if not, I leave to another aesthetician to decide) – that’s why I am not putting it too far down on your matrix.

History of philosophy, I think, might always be closer to the higher-order knowledge section, since it concentrates on figuring out conditions and historical perspectives on a subject matter, or of a philosopher’s thought on these. OR you can think that first-order knowledge applies both to me thinking about these issues by myself AND to seeing them through the eyes of a historical figure, which would set it more into the 10 square? Depends on the direction of inquiry, then.

Different aestheticians do aesthetics differently (big surprise, I know), but there’s a clear trend right now towards empirical approaches, or at least a trend towards drawing on such approaches. (I take it that doing aesthetics ’empirically’ means more than just taking artworks as explananda, least of all because portions of the sub-field that draw on empirical data and engage in experimental philosophy here aren’t concerned with artworks per se.) Overall, I would be inclined to put the sub-field in the top-right corner of 7.

Metaethics: 14

Normative Ethics: 10

Applied Ethics: 6

Suggestion: It would be easier to follow discussion on this if the squares were marked ‘A1, A2, A3, A4, B1, B2, . . .’ instead of just numbered.

That’s a good suggestion, TA. I’ll try to keep that in mind for future presentations of the matrix.

A question: does the content of a sub-field determine its place on the matrix, or does the subfield’s place on the matrix determine (what gets counted as) its content?

Another question: anyone else want to see an alignment chart? E.g. Formal epistemology: lawful good.

Hey, I always aspire to be chaotic good!

Analytic metaphysics is (or at least should be regarded as) much broader than the sorts of less-empirical and lower-order issues such as universals, 3D-4D, or material constitution. For example, I do analytic metaphysics, and I apply it to questions about social categories such as race. That’s not first-order metaphysics, but it certainly is metaphysics, and I’m doing it in an analytic way. I look at experimental philosophy results (although I don’t do it myself), and I have to pay attention to work in sociology and philosophy of science, which are more empirical, in addition to more theoretical and less empirical work. I would place more work somewhere around 8, although I think it ranges closer to 4 or 12 at various times, sometimes even dipping into lower-order questions in the third column. I would insist that it’s analytic metaphysics.

Isn’t all of science in box 1?