Just One-Third of Published Psychology is Reliable

A team of 270 researchers have now published the findings from their “Reproducibility Project”—an attempt to replicate the findings in published psychology papers—in Science, and the results are dismal. Nina Strohminger (Yale) and Elizabeth Gilbert (Virginia) discuss the findings in an essay at The Conversation:

Almost all of the original published studies (97%) had statistically significant results. This is as you’d expect – while many experiments fail to uncover meaningful results, scientists tend only to publish the ones that do.

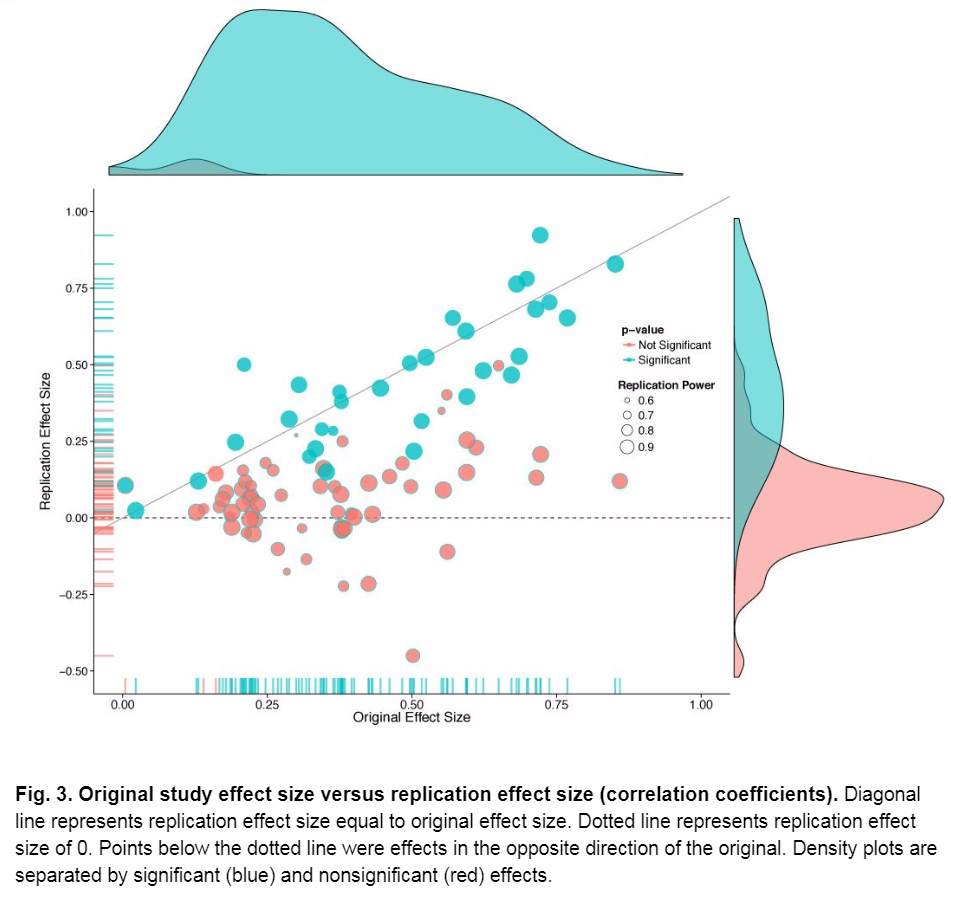

What we found is that when these 100 studies were run by other researchers, however, only 36% reached statistical significance. This number is alarmingly low. Put another way, only around one-third of the rerun studies came out with the same results that were found the first time around. That rate is especially low when you consider that, once published, findings tend to be held as gospel.

The bad news doesn’t end there. Even when the new study found evidence for the existence of the original finding, the magnitude of the effect was much smaller — half the size of the original, on average.

If you are curious about how particular original studies fared, you can look them up at the Open Science Framework website, where the full paper is also available.

Strohminger and Gilbert warn not to jump to conclusions:

One caveat: just because something fails to replicate doesn’t mean it isn’t true. Some of these failures could be due to luck, or poor execution, or an incomplete understanding of the circumstances needed to show the effect (scientists call these “moderators” or “boundary conditions”). For example, having someone practice a task repeatedly might improve their memory, but only if they didn’t know the task well to begin with. In a way, what these replications (and failed replications) serve to do is highlight the inherent uncertainty of any single study – original or new.

In conversation, one thing Strohminger drew attention to was the difference in replication rates between cognitive psychology and social psychology. Around 53% of the former were successfully replicated, while only around 28% of the latter were, which Strohminger suspects “has a lot to do with greater human variance in social than cognitive psychology.”

I did not go through the individual studies, but if you notice any that have been used by philosophers, or are of relevance to particular philosophical questions, please draw attention to them in the comments.

(And don’t get smug; imagine how low the rates would be in philosophy!)

“One caveat: just because something fails to replicate doesn’t mean it isn’t true.”

Correct. However, it does mean that it isn’t science.

To be sure, philosophy would have low rates of replication, but philosophy doesn’t call itself a science. The main problem that I have with “soft-sciences” is the power that they wield in society, and in government, whereas philosophy wields little such power. (To be sure, I don’t think that philosophy should have more power, but rather that “soft-sciences” should have significantly less power.)

But this _is_ science*: if one research team tries something and it seems to work, others should try it again. The problem isn’t that many published results fail in a replication study (that is part of the process of selfcorrection in science), the real problem is that most studies are never tested again at all. And this is a problem across all of the sciences, hard & soft.

I find this news encouraging: a sign of the growing awareness of the need for replication studies.

*Compare: weeding is gardening.

Would be interesting to know how the social psychology involved in situationist critiques of virtues theory fare. My recollection is that there are about 5-7 “experiments” that are taken to provide support for undermining the existnece of robust character traits.

This is what I’m most interested in as well. Doris’ new book already deals with the replication question (Josh May links to an excerpt in his post) but I think the situationist literature is much larger than 5-7 studies (the literature on disgust alone contains at least a dozen important experiments, for example).

Check out the Landy and Goodwin (2015) meta-analysis of disgust inductions if you are interested in how that literature fares.

Also check out this stuff by Fessler and Clark in regard to widespread moralistic implications philosophers and psychologists have tended to draw about the normative role of disgust:

“The Role of Disgust in Norms, and of Norms in Disgust Research: Why Liberals Shouldn’t be Morally Disgusted by Moral Disgust”

http://www.danielmtfessler.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Clark-Fessler-2014-moral-disgust.pdf

“Digging disgust out of the dumpster”

http://bit.ly/1faElAk

A good rule of thumb when evaluating social psychology work bearing on moral psychology is, as the above articles illustrate, whether it’s informed by evolutionary biology. One of the striking things about Doris’ new book is that he invokes social psychology to support philosophical views that are generally taken for granted among evolutionary moral psychologists. Here’s hoping that philosophical moral psychology will eventually Darwinize:

“On the partnership between natural and moral philosophy”

http://qcpages.qc.edu/Biology/Lahti/Publications/Lahti14MoralSentiments.pdf

“And don’t get smug; imagine how low the rates would be in philosophy!”

I’m no sure what is intended by this comment. One way to read it (although hopefully not the way that it was meant) would be to expect worse with regard to replicability in that area of philosophy that runs studies like the ones at issue — i.e., experimental philosophy. But, then there is no need to imagine, as we have reason to believe that x-phi isn’t facing a replicability crisis like we’re seeing in social psychology. For a nice articulation of the reasons for this, see Shen-yi Liao’s post here: http://philosophycommons.typepad.com/xphi/2015/06/the-state-of-reproducibility-in-experimental-philosophy.html

Philosophers seem to have convinced themselves that social psychology is uniquely problematic. That’s just false: there are very similar rates of failure of replication in the biomedical sciences.

https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg21528826-000-is-medical-science-built-on-shaky-foundations/

Damn, the study that skepticism about free will increases the likelihood of cheating was apparently one of the studies that failed to be replicated. There goes one of my favorite classroom examples!

For those who want to see the details on this one (Vohs and Schooler 2008) it’s at https://osf.io/i29mh/

It’s all about p-values. Look at how many medical studies, especially on diet and related issues, don’t reproduce. It’s long past time that, even if medicine and social sciences have good reason for looser p-values, and related statistical significance issues than the “hard” sciences, they still tighten up what they currently have.

You can still p-hack a smaller alpha value. By and large in my experience, the issue is that psychologists doing NHST don’t follow the rules you have to follow for the p-value to have any meaning whatsoever.

Neil is right to note that replicability problems arise in other sciences, too. Cf.: economist.com/news/briefing/21588057-scientists-think-science-self-correcting-alarming-degree-it-not-trouble

Like Justin Sytsma, though, I would also like to know what is meant by the comment, “And don’t get smug; imagine how low the rates would be in philosophy!” How can we do that hypothetical? Philosophy, except at the fringes, is much more like a humanity. There is no analogue of ‘replication.’ (In Analytic philosophy, ‘acceptance by the community’ is sometimes, I sense, seen as a rough analogue, but this is already to denature philosophy.)

JCM, Justin Sytsma, curious others — that was just meant to be a joke. I was imagining researchers starting with a philosophy paper’s assumptions and premises and seeing if they could replicate the rest of the argument. I wasn’t taking particular aim at X-phi or any specific philosophers.

I read what you said as a joke, and I know I’m in danger of acting the stereotypical philosopher who has to be told when to laugh, but I’m going to press on anyway, because I think it’s worthwhile thinking about this. For instance, the ‘Economist’ article to which I linked above gives some reasons why the replicability rate is so low, and some of those reasons – such as the poor cost/outcome ratio of replication experiments – don’t apply to philosophy, or don’t apply in the same way; and so in some ways philosophy’s ways of keeping itself honest actually look *more* rigorous than the hard sciences’. For instance, philosophy talks are followed by perhaps more than an hour of intense questioning by relevantly competent people who often have most of the relevant ‘data’ – assumptions, premisses, arguments, etc. – available to them. This allows the thesis presented by the speaker to be put under a scrutiny that is, compared to the peer scrutiny available to hard scientists (ten minutes or less of questions from people who have to take the most controversial and important evidence for the thesis as given), remarkably, even beautifully, thorough. This suggests that we philosophers should actually be more bullish about the rigour of our discipline!

It know the title of this post is just pulled from the linked piece, but it seems too strong. It’s not like we now know that “only a third of psych studies are reliable.” Just as one study isn’t the final word on a topic, this diverse group of replication attempts isn’t the final word on all the various areas of psych. And it’s not representative of all of psychology (only some areas and some studies were tested).

The project’s results are definitely bad news, though. I hope it motivates structural changes in psych and keeps philosophers from just appealing to one or two studies to establish a controversial claim. There are perfectly fine ways to appeal to experimental data, despite Repligate. On these issues, I recommend this excerpt from John Doris’s new book:

http://sometimesimwrong.typepad.com/wrong/2014/09/guest-post-by-john-doris.html

It should be noted that the project shows that studies with lower p-values and larger effect sizes are much more likely to replicate successfully. This is actually very good news: it means that in principle, the methods/statistics work, and it would be fairly easy, e. g. for journals, to implement regulations discouraging hackability.

Don’t worry too much about this. By its own lights it’s only got about a 1/3 chance of being reproducible.

As a side note:

“Almost all of the original published studies (97%) had statistically significant results. This is as you’d expect – while many experiments fail to uncover meaningful results, scientists tend only to publish the ones that do.”

…which is why we (in psychology and elsewhere) desperately need to finally make scientists pre-register every study. (More at: blog.givewell.org/2011/05/19/suggestions-for-the-social-sciences/ )

I hope philosophers will take two things from this. First, an appreciation of the HUGE amount of effort and time that the psychologists involved in the project took to try to measure the epistemic status of published results in their discipline. Second, an appreciation of just how hard it is in science to get any interpretable effect at all. Coming up with a hypothetical counterexample to an empirical claim is next to meaningless in this context unless you can also think of how you might obtain evidence for your alternative interpretation. Otherwise all that is accomplished is pointing out that empirical results involve induction.

I think there is a mistake, or at least something quite misleading in the Conversation essay.

“What we found is that when these 100 studies were run by other researchers, however, only 36% reached statistical significance. This number is alarmingly low. Put another way, only around one-third of the rerun studies came out with the same results that were found the first time around.”

But even with genuine effects supported by the evidence, you wouldn’t expect *the same* results the second time around.

Suppose we want to know whether a coin is ‘fair’. You flip it 100 times and 60 times it comes up Heads. You report that it is biased toward Heads, your evidence significant at the .05 level (.028, using Wolfram Alpha). Now Kim tries your reproduce your results. Only 57 Heads in 100 flips! Not statistically significant at the .05 level! (.097)

Is this disturbing? Should you retract? Kim’s results are *more* evidence that your conclusion is correct. They *support* your claim. When the effect reported is due to genuine bias, we don’t expect to get *the same* result of 60 Heads in a repeat experiment. Getting the statistically insignificant 57 Heads (at least 57 is more than 5% likely when a coin is unbiased) supports the hypothesis of bias.

I am not, of course, trying to say that everything’s fine in psychology, but I think the problems may be exaggerated.

Jamie, this isn’t right. We shouldn’t expect *the same* results the second time around only if “the same” is read in a way that’s not relevant here. Of course, we shouldn’t expect “the same results” if this just means the same raw or average data (like your 60 vs. 57). But we *should* expect “the same results” if this means—and it is what the researchers mean—that there was a statistically significant difference in whatever was measured. That’s precisely what attempts at replication are examining. So we *should* expect the same results, because “the results” here are *that there was a statistically significant difference*.

Consider a different and clearer example. Q: Does drug X decrease recovery times? An experiment randomly assigns participants to receive a placebo (control group) or drug X (manipulation group). Results: Average recovery times decreased with the drug (24 hours for Placebo; 12 hours for drug X). The difference might be a fluke, but we have evidence that it’s not, because a statistical analysis yields p-value<.05. The difference in recovery times is statistically significant, and we thus have some support for the hypothesis that drug X reduces recovery times.

Now, if we try this again in an attempt to replicate, then we should not expect to find 24 and 12 hours exactly, but *we should expect to find a decrease and one that's statistically significant*. Suppose the replication attempt finds 24 hours for placebo and 20 hours for drug X and this difference isn't statistically significant. Then it *does not* support the hypothesis that drug X decreases recovery times. It could have been that, despite random assignment, more healthier people got into the drug X group by chance. Without a sig. p-value, we can't reject this alternative. (We also can't accept the null hypothesis unless there's enough statistical power in the sample.)

The main claims of the Reproducibility Project are that 36% of studies didn't find a statistically significant difference like the previous studies did. That's bad. It's not necessarily the end of the world, as Jamie says, but not for the reason he provides.

Hi Anon Junior Person.

I assumed by “the same” the authors meant “just as significant pointing in the same direction”. But I don’t see why you think that’s what we should expect. Or, I guess you are saying that by “the same” you mean “significant at .05” if the original study was significant at .05; but I don’t think that’s what we should expect either. I think this is a mistake (I’m going to try to blockquote here, I hope it looks okay):

That is not true, in general. It depends on further statistical properties of the data.

I know you think your example is clearer, but mine has the virtue of having particularly simple data with obvious statistical properties. In my example, even though the second trial does not pass the significance test on its own, it does indeed provide extra support to the results of the first trial. To see this, just combine the trials into one. The combined experiment has 117 Heads out of 200 flips, and this supports the hypothesis of bias toward Heads at the .01 level (which the original experiment did not). A second trial yielding just 55 Heads still adds support. If it were only 51 Heads on the second trial, that would reduce the support rather than increasing it. (I did these calculations on Wolfram Alpha — for more complicated examples I would have to think more than I’m willing to or else ask for help.)

In my opinion, a Bayesian approach to this question is more illuminating, but the issue has been framed in “statistical significance” terms so I’ve continued in that framework.

Thanks for the reply, Jamie. By “the same results” I didn’t mean (and the researchers don’t mean) both studies should have a p-value of exactly .05 (or any other exact value). The question for replication is: Will we again, like the original study, find a statistically significant difference (that is, a difference between groups that has a p-value<.05)? That's "the result" that is supposed to be "the same"——not how low the p-value is, but whether it's significant or not (that is, whether it's less than .05 or not).

Replication attempts are *not* trying to find the same "level" of significance (e.g. exactly .05 or exactly .01 or whatever). For example, if Original Study found a difference between groups (say 24 hours vs. 12 hours) with a p-value of .04 and Replication Attempt found a similar result (say 24 hours vs. 18 hours) with a p-value of .01, then they found "the same results" (in the relevant sense) as Original Study. Of course, there are many things in a study worthy of the name "result"—raw data, averages, p-values, effect sizes, etc. But replication attempts are chiefly looking for whether there is "an effect" which just means *whether there is a statistically significant difference between groups*.

So the researchers in the Reproducibility Project are *not* saying that we should expect in a replication attempt that any of the following should be the same: (a) the raw data; (b) the central tendencies, like means or medians; (c) the "level" of significance, like p=.04 vs. p=.01; (d) the effect sizes, like d=.2 vs d=.8. Rather, a result is replicated *when researchers again find a statistically significance difference*, where p<.05 (so it could be .04, .01, whatever). Again, it's an all-or-nothing issue.

In the key 36 studies of the Reproducibility Project, they are deemed "replicated" just because they found what we'd expect from a real effect: there was again a statistically significant difference between groups (and presumably in the predicted direction, like a decrease or increase). That's the expectation the researchers are referring to in the quote you take issue with. I think "same results" was definitely poor word choice, but they're definitely not saying what you think they're saying.

Yes, sorry, I understood that’s what you meant, maybe I just put it badly. I think “significant at .05” includes results that are significant at smaller probabilities, right?

So here is one thing I think is a mistake: that when an experiment supports a hypothesis at the .05 level (or stronger), we should expect a replication to support the hypothesis at the .05 level. Indeed, even assuming the hypothesis is true, it is still often reasonable to expect a replication to fail a significance test at .05. A biased coin will often come up Heads only 57 times out of 100 flips, after all, and that experiment fails to support the hypothesis of bias at the .05 level of significance.

What my simple example shows, in any case, is that a failure of the replication to be significant at the .05 level does not mean that the new experiment is troubling. It can easily provide more support for the hypothesis, making it rational to increase our confidence in it.

Ah, I see how you’re using “significant at .05”—namely, just to mean statistically significant. If your point is just that failures of replication (failures to find a statistically significant difference) don’t necessarily mean that the effect isn’t there, then that’s of course true, for various reasons. One key reason is that we can’t accept the null hypothesis from a failure to find an effect (sig. diff.). “Absence of evidence isn’t evidence of absence.”

But your claim is stronger—namely that we shouldn’t expect to find a sig. diff. when attempting to replicate a previous experiment that did find one. This amounts to claiming that we shouldn’t expect to be able to replicate previous studies. I’m puzzled by this. Again, of course a failure of replication doesn’t alone warrant the conclusion that there isn’t a real effect there. But you’re saying more: we shouldn’t expect a replication (=find a sig. diff.) *because* a failure to replicate might even yield data that actually *supports* the hypothesis that there’s an effect. Sure, this technically could happen if one combines the data from the two experiments, runs another significance test, and finds a sig. diff. But, unless one does that, the failure to replicate is prima facie problematic, and presumably because what I’m saying is right—namely that we should, in general, expect real effects to replicate.

I mean, why shouldn’t we, in general, expect effects to replicate? Again, certainly failures to replicate don’t provide strong evidence against the hypothesis that there’s a real effect there. But, even given this fact, it seems we should expect that most real effects will replicate.

To be clear, I appreciate the discussion! I’m just trying to get clear on this.

Hi; I can’t “Reply” to your last, presumably because we’re at the end of the functionality of the software.

“Statistically significant” doesn’t always mean significant at the .05 level. That’s a common level in social sciences, but the bar can be set anywhere, and I don’t like the idea that there’s something especially important about .05 — it’s just a convention. That’s why I used the more precise terminology.

Okay, I don’t love the look of the blockquotes, but it does make it clear that I’m quoting, so I’ll use the tag.

Right.

No, that’s not right. It seems like you are saying that the evidence doesn’t support the hypothesis unless the experimenter actually calculates certain statistics, but I’m pretty sure that’s not what you mean.

Just tell me what you think about the coin example. Do you think that the second experiment that finds 57 out of 100 coin flips are Heads supports or undermines the hypothesis being tested?

Because often real effects don’t produce statistically significant results.

Okay, I think I see the disagreement here. I’m assuming the name of the game in experimental psychology here is null hypothesis significance testing (NHST). Maybe it shouldn’t be, but it is. At the very least, when one aims to replicate, the main aim is to look for statistically significant differences again (which, yes, in this context is at the .05 level). In NHST, a non-null hypothesis is confirmed only by finding a sig. diff. Just looking at the raw data or central tendencies (e.g. averages) isn’t enough in this game.

So, about your coin example, I don’t see how a non-sig. result (57/100 heads) supports the hypothesis that the coin’s biased, *at least according to the rules of NHST*. Maybe on some other framework it does, but not NHST. In NHST, if the hypothesis being tested is that there is a real causal difference, looking just at the raw data (e.g. central tendencies) is insufficient. That’s the whole point of the sig. test. It’s supposed to provide evidence that (roughly) the differences observed were not likely due to chance, and therefore we have some evidence of a causal relationship. If you flip a coin 100 times and it lands on heads 57 times, you do not have evidence of a biased coin by the standards of NHST.

Maybe you’re assuming a perfect environment in which an unbiased coin will always land heads 50 times when flipped 100 times. (So even 51 heads would be evidence of bias.) But that’s why this example is misleading in this context. Sig. testing is pointless in this example (if understood in this way). In psych studies, though, the environment isn’t perfect and it’s nature isn’t fully known, so we can’t infer much if anything from raw data or central tendencies (the “descriptive statistics”). We have to use inferential statistics to get evidence about whether the difference observed (e.g. 24 hours vs. 12 hours) was not just due to chance. Compare a poll with error margins. If Trump is 5 points ahead of Bush, that means *nothing* if the margin of error is 5. We can’t infer anything. It does not confirm the hypothesis that Trump is ahead. Similarly, if drug X decreases recovery times by 5 hours, we can’t infer anything if the result is non-sig. That’s the rules of the game with NHST at least.

Just to clear up a couple of things: I was not assuming that an unbiased coin always lands Heads 50 times in a trial of 100 flips! I was obviously assuming that it has a smallish chance of landing Heads (at least) 60 times, and a slightly larger chance of landing Heads (at least) 57 times, since I reported those chances and I was using them in the argument. You did notice that I had reported those chances, and that they were not zero, right? So then obviously I was not assuming that the chance of the unbiased coin coming up Heads 50 out of 100 flips was 100%.

Similarly, it’s very surprising that you think it important to inform me of this:

Right, that’s why I calculated those statistics and reported them for the coin-flipping example. Did you understand the point of those numbers? I made up an example for which the numbers are easy to work out, and then I gave you precisely the numbers you are claiming are important. I did not give you any central tendency numbers and I did not merely give you raw data.

Ah, good example.

Suppose G-poll reports Trump 5 points ahead of Bush, and the margin of error for the poll is 4.9. Trump is in the lead, we infer! Then H-poll reports Trump 5 points ahead of Bush, but for H-poll the margin of error is 6 points (small sample). Then I-poll reports Trump ahead by 4.5 points, but its margin of error is 5 points. Then J-poll reports that Trump is ahead by 5 points, but its margin of error is 5.5 points.

Having learned the G-poll results, we thought Trump really was ahead. Now we get the H, I, and J results, with their margins of error reported. Do you think we should now be more confident that Trump is really ahead, or less? If some people are playing by rules that tell them to be less confident, it’s a good bet they are among the people who have been embarrassed by Nate Silver.

Thanks for the clarification. (For the record, I didn’t think the best interpretation attributes to you the assumption that an unbiased coin always lands Heads 50 times in a trial of 100 flips. I was just speculating about a possible assumption one might make that would help render more plausible, by my lights, your claims that I dispute. I didn’t mean to insult by exploring that assumption.)

About the Trump example: Whether we should believe that Trump is ahead depends on further details of the polls—e.g. sample sizes, sampling methods. The same goes for similar situations in experimental psychology. Warranted confidence in the null hypothesis depends on multiple quality experiments, effect sizes, power, etc. But I’m not the one claiming that we can infer much from non-significant results. The burden is on you to say why we can (in particular, that observing a difference between groups supports rejection of the null hypothesis, even if the difference is non-significant).

I’d love to see a general argument—not just some hypothetical examples of false negatives. We need an argument showing that, in general, we should expect that real effects will *often* not replicate (that Type II errors or false negatives are common).

I guess it depends on how weakly we can interpret “often.” Perhaps we don’t disagree all that much. I certainly grant that one failure to meet the .05 significance level should be taken with a grain of salt, especially if the p-value isn’t terribly far from .05. It is a somewhat arbitrary cut-off, and failure to meet it doesn’t necessarily mean we can accept the null hypothesis. And, again, I completely agree that the results of the Reproducibility Project aren’t devastating and can easily be exaggerated.

Okay, well, when you brought it up as an example, you didn’t say anything about sample sizes or sampling methods. That makes sense, because if the confidence intervals are computed properly, they already incorporate the relevant information about sample size and method. So I think this is a red herring.

Am I right that you think the new polls in my elaboration of the example (assuming the sampling methods were okay) do not provide extra evidence in favor of the hypothesis that Trump is leading? I’m saying that is a mistake.

And of course you can infer things from results that do not pass a significance test. You can infer almost as much from a result that almost passes a significance test as you can from a result that barely passes. The threshold is completely arbitrary. The evidential strength of experimental results is arranged on a continuum.

I think I’ve said enough now, and I feel like I would just repeat myself to address the rest.

Just noticed that John Quiggin at Crooked Timber has explained in a more rigorous way the point I was trying to make.

too many folks with PhDs in social “science”aren’t actually philosophically aware/educated (in the narrow sense of knowing what their tools are doing and why, let alone what they may be missing and or masking) but are rather technicians socialized into using pre-established/engineered techniques/technologies for certain set kinds of problems/results, leads to a kind of tyranny of the means, and as we know from the nascent work into cog-biases pointing out to them that they are in error is just likely to entrench them deeper into their deeply worn work habits.

“If you aren’t simply making an ingroup claim to authority, then I just don’t know what your argument is. To whit: operationalizing isn’t the point here (which you seem to realize, but argue nonetheless). The point is operationalizing concepts guarantees nothing other than the explananda are adequate to the uses of a given experimental apparatus at a given point in time. The question, though, is the degree to which that apparatus limits adequate theory-formation and thus progress in the field. Crying ‘operationalization’ is simply a red herring. Neuroscience, I take it, is interested in more than simply confirming the utility of its apparatuses to generate the results those apparatuses generate. If so… It’s not brain science, but then it’s not rocket science either.” @ https://rsbakker.wordpress.com/2015/08/24/alienating-philosophies/

I am conflicted here. On one hand, I think/hope the headline (here and at the Conversation piece) was intended as click-bait. On the other hand, I kind of hope it wasn’t because the egg-on-face would be…. delicious. Is that immoral of me?

In the last thread we were arguing about what bad effects (if any) a lack of conservative thinkers or ideas in a field could have. I submit that the current replication crisis in psychology is such a bad effect. I quote from the paper:

“14 of 55 (25%) of social psychology effects replicated by the P < 0.05 criterion, whereas 21 of 42 (50%) of cognitive psychology effects did so."

Social psychology is very biased towards left-wing viewpoints, and this leads to researchers "fishing" for ideologically acceptable findings and accepting them less critically than they should. Obviously this is not the only problem contributing to the replication crisis. There are other incentives leading researchers away from truth, including financial incentives, publish-or-perish, and so on; research standards are not as high as they should be; and there's a woefully bad understanding of statistical methodology. But ideological bias is an important component.

Now, no doubt conservatives also fish for findings they like. But, as Haidt, Jussim, etc. have pointed out, ideological diversity in a field ensures that when progressives seek results confirming their viewpoints and conservatives seek results confirming theirs, there will be plenty of people on the other side to poke holes in their bad arguments.

You write that “Social psychology is very biased towards left-wing viewpoints.” In Political Diversity Will Improve Social Psychological Science, Haidt et al say that in psychology “84 percent identify as liberal while only 8 percent identify as conservative.” They don’t distinguish between social psychology and cognitive psychology. Do you have data that does?

Also, again, such disparities on their own are insufficient to show bias (e.g., that less than 1% of a given population believes the earth is flat is not evidence of bias against flat-earthism).

No, I confess that my belief that social psychology is more left-wing than cognitive psychology is based primarily on anecdotal impressions (albeit with some familiarity with both disciplines). I was also thinking that social psychology studies more inherently politicized topics, and thus is more likely to be infected by progressive bias even if there are similar proportions in both fields.

And yes, I agree that disparities on their own do not show bias; but I think Haidt et al. have gathered ample evidence of bias in social psychology beyond mere numerical disparities.

Justin, are you suggesting that adoption of conservative positions is as unreasonable as believing the earth is flat? In reading many of your comments, both here and on the earlier thread, you often bring up ‘reasoned judgment’ as the explanation for disparities in representation. Are you just saying that progressive positions are simply the reasonable ones to have and this explains why they are so more prevalent among philosophers? This strikes me as exactly the sort of claim that conservative philosophers are complaining about.

To be clear, I think many conservative positions are unreasonable. I think many progressive positions are as well. I just want to be clear about what you are (and have been) saying.

“Justin, are you suggesting that adoption of conservative positions is as unreasonable as believing the earth is flat?” No. It was just an illustration of the point that disparity in beliefs does not itself imply bias.

Cf. “Can high moral purposes undermine scientific integrity?” [http://www.rci.rutgers.edu/~jussim/papers.html]

Replication is hard. It is even harder if you know you will be part of a group of 100 other researchers trying to replicate studies. The conclusion is not that the studies (that failed to be replicated) were not scientific. The conclusion is rather that we do not fully know why there is a statistical correlation even when we find one. For philosophy, this is good news because it is a step towards more scientific humility.

I would be interested to know where this leaves most of the studies that philosophers cite. Not just the ones you may find in, e.g. a philosophy of mind paper, but the ones that are used to support the existence of implicit bias and stereotype threat in the profession.

See the paper “Can high moral purposes undermine scientific integrity?” for discussion of stereotype threat and sex difference research in psychology:

http://www.rci.rutgers.edu/~jussim/papers.html

Regarding the Implicit Association Test (IAT):

in this talk (circa 75 mins.), cognitive psychologist Daniel Levitin characterizes the IAT as “a completely bogus test”:

http://www.lse.ac.uk/newsAndMedia/videoAndAudio/channels/publicLecturesAndEvents/player.aspx?id=2838

Levitin also refers to his withering WSJ review of the IAT creators’ recent book ‘Blind Spot: Hidden Biases of Good People’:

http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887323829504578272241035441214

For discussion of a recent IAT meta-analyses:

https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/pop-psych/201502/the-implicit-assumptions-test

For research challenging the significance attributed to the low levels of implicit-explicit correlation produced by the IAT, see pp. 28-29 for Hahn & Gawronski’s commentary (“Do implicit evaluations reflect unconscious attitudes?”) and pp. 52-53 for Newell & Shanks’ agreement with it:

https://dl.dropboxusercontent.com/u/2397729/Newell%20%26%20Shanks%20%282014%2C%20BBS%29.pdf

See also this list on Jussim’s blog of studies that have failed to replicate in the past: https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/rabble-rouser/201208/unicorns-social-psychology

In general, the priming literature is on pretty shaky ground. This calls into question not only appeals to stereotype threat but also situationist philosophers appealing to social psychology data in support of their views.

“the priming literature is on pretty shaky ground”. That’s certainly false. Perhaps you meant to write that “the behavioural priming literature is on pretty shaky ground”? That’s probably false too, but not obviously false.

A number of commenters on this thread have very reasonably raised the question as to whether the replication problems found for psychology studies also arise for experimental philosophy studies. There is actually a great deal of information available about that question, and you can see it all compiled at:

http://pantheon.yale.edu/~jk762/xphipage/Experimental%20Philosophy-Replications.html

As this page shows, the majority of experimental philosophy studies do seem to successfully replicate, but there are also some that clearly do not replicate. In any case, my sense is that the field of experimental philosophy as a whole has made substantial methodological changes in light of the recent replication crisis and that some of the methods we were using in the past have all but disappeared from contemporary practice.