Hobbies of Philosophers: Steff Rocknak

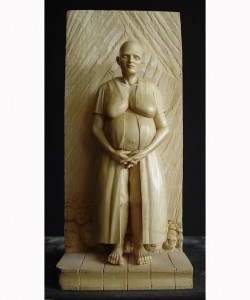

For this installment of “Hobbies of Philosophers”, I talked to Steff Rocknak, professor of philosophy at Hartwick College. Steff works on Hume, Quine, philosophy of art, and philosophy of mind. But she also has a successful career as a sculptor—it is certainly much more than a hobby, so in this case, the title for this series is terribly inapt given the central importance of her work as an artist! She was kind enough to answer some questions about the sculpting side of her life, and to share some images of her work with us. (The above photo is of “The Queen”, lifesize, basswood). Normally things get edited out of these interviews, or we insert some commentary, but I was so struck by everything that Steff said that I have left her responses completely intact.

If you are similarly struck by the images of her work, the discussion here, or both, and are located anywhere near Brooklyn, Steff currently has a show at the Sculptor’s Guild Gallery, and is giving an artist’s talk there on Thursday, April 2 from 6-7 (reception to follow). More information is available here.

You can also visit Steff’s website.

Most of us struggle with maintaining one career, and you really do have two separate successful careers. Can you talk for a moment about how you have time to balance your career as a sculptor and your career as a philosopher?

Generally, I do philosophy in the morning and sculpt in the afternoon (unless I’m teaching). This usually works for me, but I am very slow. With committee work and a 6 course load, I just don’t have the time to produce a high volume of work. However, I do find that if I work just a couple of hours a day on a sculpture that I make progress. It’s slow, but eventually I get there. I have to admit though, I’m a workaholic; I don’t take a lot of time off.

Could you talk a little about how you became a sculptor, and what drew you to the kind of work that you do?

I have been drawing and sculpting people for as long as I can remember; the human form speaks to me like nothing else does. Also, I was very fortunate to have grown up surrounded by people who enjoy making things. My dad worked as a high school art teacher for a while, as well as a cabinet maker and a carpenter, and my mom was constantly restoring furniture, and making things, e.g. sweaters, dolls, etc. The same goes for my two brothers. I also spent hours with my next door neighbor Garrett, making wooden guns, dolls, ships, robots and forts (in addition to drilling large holes in the barn walls and racing our dads’ belt sanders). Meanwhile, one of my parent’s good friends, Ted Hanks, was a well-known bird carver. If you have been to the L.L. Bean mother ship in Maine, you’ve probably seen his wooden ducks flying out of the store’s trout pond. So, at an early age, I saw what could be done in wood—beyond forts and toy guns. At the time, though, Ted’s work seemed like magic.

It was not until I returned home from a junior year abroad in Rome that I began to work seriously in wood. Although I had gone to Italy to study painting, I found that I was much more interested in sculpture. I spent hours drawing and studying the work of the greats, e.g. Donatello, Bernini and Michelangelo. I’ve never “formally” studied sculpture, i.e. I’ve never taken a sculpture class, but I have certainly studied sculpture. I returned to Europe ten years later, as a Junior Fellow at the Institüt fur die Wissenschaft vom Menschen in Vienna, Austria. I spent most mornings working on my Ph.D. thesis, but in the afternoons, I toured the many wonderful museums in Vienna, where I gravitated towards the medieval wood sculpture. I was impressed by the figures’ playful, stylized hair, particularly when juxtaposed to their calculated and dignified expressions. In 2006, after presenting a paper on Quine at a philosophy conference in Kazimierz, Poland, I made a beeline for the medieval wing at the National Museum in Warsaw. I was floored by what I saw. The carved figures in this collection are, for the most part, very stylized, but not in some kind of contrived contemporary effort to be “different,” “new” or “shocking.” Rather, they are wrought with an almost tortured emotion. The suffering was so visceral, so genuine, and beautiful, that I literally gasped. I got so close to the work that by the time I left, I had accrued my own personal entourage of security guards.

How did you start working with wood?

I was surrounded with woodworkers as a child, so it was natural choice for me. And once I started carving, I was hooked; I became thoroughly seduced by the warmth and unpredictability of the wood, especially the grain.

Can you talk a little bit about how you have developed your career as a sculptor and your career as a philosopher alongside one another? What are the particular challenges you have faced? Were you always sort of “doing both”, or did you go through periods of focusing more on one or the other?

Once I started working in wood, I never stopped. I’ve slowed down at times, for sure, but I’ve always had a piece going, even if it meant that I had to work in my office or on my living room floor. Sculpting has always been a safe-haven for me. I am self-taught, so I’ve had no overbearing, control-freak, agenda-setting, and/or sexist professors to deal with. Nor do I have to deal with editors or referees. Aside from commission work, I do exactly what I want, and how I want to do it. In this respect, I have complete control over my creative process.

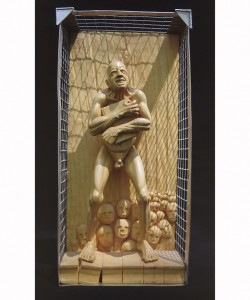

(images: “The Philosopher” and “The Academic”. Both are 10” tall, limewood.)

Nor is my sculpture an explicit argument; for the most part, it’s an emotional reaction to the world, similar to say, the horror we might feel when we see a car wreck. Although this kind of reaction can be construed as a kind of statement, it’s really not something you can argue with, just as you generally don’t, or shouldn’t, argue with someone about her reaction to the car wreck, even if it’s wildly inappropriate. Similarly, the person who has the reaction does not, generally speaking, need to explain it—you either get it or you don’t. For the most part, this is why I don’t feel the need to write theoretical “artist statements,” i.e. philosophical explanations of my work. My figures are my almost involuntary reaction to the “car wreck”—you either get them or you don’t. I didn’t need to understand Polish, or the historical/religious context to relate to those figures in Warsaw. I did not need to read an artist statement. Body language is, for the most part, universal, and so is good figurative art.

However, if the art object at hand (regardless of the medium) is unrecognizable, then the need for a written explanation becomes apparent. I get that. But I just don’t think that this combination of mysterious object/theoretical explanation is particularly effective. Instead, in many cases (but surely not all), it strikes me as contrived. For related reasons, I am not driven by a need to make “new” art. Rather, I’m just trying to capture my reaction to the world as honestly as I can. Best, I think, to not confuse the particularly American pathology for the “different” and the “individual” and the “new” with good art.

How similar do you feel like the actual process of sculpting and of writing, or teaching, or reading philosophy is?

As I mentioned above, I don’t think that my sculptures are explicit arguments, whereas most of my philosophy, to date, has consisted of arguments/explanations (I don’t write aphorisms). However, there are some similarities between studying another sculptor’s work, e.g. drawing a piece by Michelangelo and reading a philosophical text. Ideally, in both cases, we try to, respectively, observe and listen to the work at hand, What decisions did the artist/philosopher make and why? Of course, there is room for interpretation in both cases, but initially, if one’s real intention is to understand what is going on, it’s best to stick as close as possible to the object/text. So, taking the time to understand a certain sentence feels very similar to capturing a hand gesture in as much detail as possible. At the very least, in both cases, I feel like I have had an effective conversation with the artist/philosopher.

And of course, when I’m sculpting, I have to deal with a lot of technical issues. I’m not just, say, recoiling in horror at the “car wreck”—I’m thinking about how I can most effectively recoil. Granted, sometimes this technique is rather invisible; I’ve sculpted for so long now that there are times when I don’t really have to think about what I’m doing. Yet there are other times when I have to consciously analyze the problem at hand, without losing sight of the emotion behind the piece (i.e. the “recoil”). This analytical process is similar to the process employed in the kind of philosophical analysis I do (sans the “recoil”).

Could you tell us a bit about one of your pieces in the show you have going on now? Or, if you prefer, some other recent piece?

There are two pairs of figures that might be of particular interest to the Daily Nous audience: “The Academic” and “The Philosopher” [above], and The Queen [top] and the King [below]. Both are, in some respects, reactions to my experience as a female philosopher, especially if you read The King as a “philosopher king.”

(“The King”, lifesize, basswood)

I’d also like to talk a bit about the Edgar Allan Poe commission, which was my first major public art piece, and my first bronze. This piece was enlarged from a wooded model that I carved in 2012, and was permanently installed in Poe Square in Boston, MA in 2014. This figure captures a complicated Poe: he was born in Boston, but he had a very contentious relationship with the Boston literary establishment. Poe geographically associated these writers with the Frogpond in the Boston Common; he thought that they croaked like “frogs.” And thus, my figure dismisses them (and the Frogpond behind him) as he walks towards the house where he was born. Once again, I drew on my experience as a female philosopher; most women in this field know what it is like to be an outsider. Poe however, is an outsider that made it home—at least in regard to his work.

Yes! Seems like a good place to end. Thanks so much, Steff, for sharing insight into your work and life with us. It was a pleasure to talk to you.

(“Poe Returning to Boston.” 5’8”—Poe’s actual height—bronze.)

Suggestions for future editions of Hobbies of Philosophers are welcome; please email them to us.

– Michaela