Teaching As If Our Students Were Not Future Philosophers

Since most of our undergraduate students are planning to go to graduate school in philosophy and become professional philosophers, it makes sense that the undergraduate philosophy curriculum is typically filled with courses that prepare them for that future. Their courses should introduce them to the way that contemporary professional philosophers understand their field, teaching them the theories, jargon, technicalities, distinctions, subdisciplinary boundaries, and so on, so that they will be able to join the specialized conversations of academic philosophy.

But, imagine for a moment that most of our undergraduates—even most of philosophy majors—were not going to have careers as philosophers. Would it still make sense to teach them as we do?

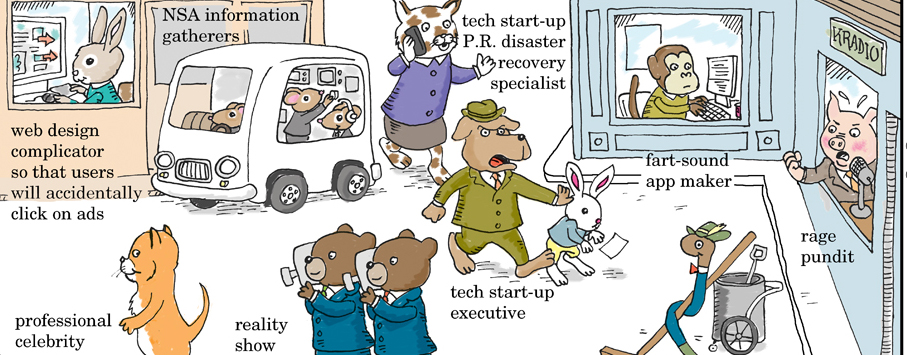

(art: “Richard Scarry’s 21st Century Busy Town Jobs” by Ruben Bolling)

I teach philosophy courses at Georgia Tech, which does not have a Philosophy Department and does not offer degrees in Philosophy. Most of my students are preparing for careers in engineering. I understood all along that I was not preparing students to be professional philosophers, but the design of my courses still carried some of the baggage of grad-school preparation. My way of teaching is now entirely different, with very different aims. (About which, for whatever it may be worth: http://bit.ly/1KfOpEc )

“Since most of our undergraduate students are planning to go to graduate school in philosophy and become professional philosophers” — where is this the case?

You might want to adjust the settings on your sarcasm detector.

Thank you, Brock. Perhaps I need to work on my delivery.

I greatly appreciate this topic, but I think the way it is framed implicitly caters to the elite and privileged (as well as the totally clueless) among us. How many philosophy professors would agree that “most of [their] undergraduate students are planning to go to graduate school in philosophy and become professional philosophers”? How many of them have to “imagine” the opposite? And how many of them that would agree are just mistaken about what their students really aspire to do in life?

At my present job, more oriented towards teaching, maybe 5% of the undergrads I teach are planning on becoming professional philosophers. At the much more prestigious liberal arts school where I did my undergrad, I suspect that of the students in it was maybe only around 15%. Even many of the philosophy majors there were not planning on becoming professional philosophers, but going to grad school or law school or doing a double-major. And even in the upper-level classes, philosophy majors were not always the majority of students.

I am sure there are professors somewhere who teach classes filled with aspiring professional philosophers , or who think they do, but my guess is that it describes the actual experience of very few.

I was assuming the first sentence should have read “most of our undergraduate philosophy majors . . .”, though even that may not be true.

The opening sentence was a joke people.

. . . and beware of Poe’s Law.

I think that doing this well requires getting excited about the project. The fact that so many teachers in the profession bemoan teaching intro courses is pretty sad. All things considered, getting a business or engineering student to buy into the philosophical perspective and develop some of the rudimentary tools of careful contemplation is a much bigger accomplishment than getting a philosophically minded kid to understand the most subtle points of Theory X. I enjoy doing philosophy at a high level, but I also still revel in the kind of initial discovery that can happen in the intro classroom.

Perhaps maths undergraduates should not really do maths, just adding and subtracting, since they most of them aren’t going to go to graduate school.

David, I would suggest there’s a difference between “doing maths” and engaging in graduate- or faculty-level inquiry and publication in mathematics. Likewise, there is a difference between “doing ethics” or “doing philosophy” and engaging in graduate- or faculty-level academic discourse in philosophy.

I remember taking a teaching seminar where the lesson that stuck with me the most was ‘not many of your students are going to love philosophy like you do.’ This was somewhat of a ‘wow’ moment for me, and it made me realize the point you’re making in this article- that when I start teaching undergrads, I need to keep in mind that I am teaching people who are not looking to become philosophers. However, this article made me wonder if this mindset causes any harm to those who are considering professional philosophy.

It made me realize that as an undergrad, few of my professors treated philosophy like something to pursue, and some actively told us not to pursue it. When it came time for me to apply for graduate schools, I felt a little (okay, not a little, very) lost. Even those who knew I was a philosophy major did not discuss graduate school options with me. I felt like I lacked a lot of guidance on how one goes about thinking about which schools to apply to, how to write a good statement, etc. Once I started a graduate program, I felt like I should had taken different/more classes as an undergrad and known more about certain prominent figures. I was kind of blown away by the philosophy training many of my peers seemed to receive from undergrad, and I am assuming this is because a lot of them were treated as future philosophers. Perhaps I am to blame since I did not heavily seek out the guidance I needed, but then again, I also did not know what kind of guidance to really seek out as an undergrad philosophy major.

Gotta say the sarcasm was a bit subtle, Justin. But great question, one we should be considering carefully, perhaps especially since some changes to the way we teach philosophy might make the philosophy major (and minor) more attractive to underrepresented populations (e.g., women and blacks; in the US women phil majors has been stagnant at about 1/3 for decades)–we’ll never increase the proportion of these populations at the grad level and beyond if they remain so low at the undergrad level. An important step in the right direction would include getting grad programs (even top ones) to put more effort into teaching grad students how to teach. If we all knew more about good pedagogical techniques, it would likely lead us naturally towards making our courses more useful for all students, including the vast majority who won’t go to grad school in philosophy.

On a related note, if anyone has tried to include a ‘professional development’ module (or course) into their major, I’d love to hear about it. As DUS here at Georgia State, I’m considering how we might give students a better sense of how to use what they learn and their being a phil major to help prepare and market themselves for a wide range of careers (and grad programs). Yes, it’s easy to say such work should be off-loaded to career services or some goofy freshman course on ‘succeeding in college and beyond’, but I think we are giving our students particularly useful skills for lots of jobs (perhaps more if we took Justin’s question to heart), and we should give them some guidance on how to make the most of it. In any case, I think doing so would be good for the students and good for us if we want to attract more people to philosophy.

This is a general question/comment, but I’m replying to Eddy simply because he is someone who may have some particular insight into the question (given his position as DUS).

Here goes….

Is there any reason why a philosophy department should only give out degrees in “Philosophy”?

For example, which of the following, which would look/sound better on an undergrads resume who was not intending on going to grad school?:

B.A. Analytical Reasoning, or

B.A. Philosophy

I’ve been thinking, for a while, that a basic “Philosophy” major is not nearly descriptive enough for undergrads not looking to go to grad school. This isn’t true for, say, English or History. Everyone pretty much knows what those majors are about.

The public perception of our discipline has hurt the basic “Philosophy” major. If everyone thinks of philosophy and philosophers as those out of touch with the real world, then we are potentially harming philosophy undergrads by not shielding them from this mischaracterization.

Yes. The best solution is to package the philosophical literature in a way that it becomes marketable for the competitive economy of our day. E.g. see China’s workforce. Had a look? Good, now change all philosophy courses into something that is marketable. Perhaps, we should make it online too. It’s just what our students want, and what the students want must be good for them.

Right. Too much student=consumer is bad. But what we deliver has to be somewhat practical, right?

Gingerbread house building is good in and of itself. It’s worthy of pursuit regardless of its practical benefits. But we probably shouldn’t fund a gingerbread house building department. If you want to build gingerbread houses, do it on your own dime.

Literally no one has to have a degree in philosophy to do philosophy. If a philosophy degree is like a gingerbread house building degree, then the discipline is in trouble.

annonGrad, that’s a bit too quick and quite a bit too snide.

The goal, at least for me, is to make serious, critical, philosophical thought something that is vital and engaging for students in disciplines other than philosophy (i.e., all of my students), but in a way that is rigorous and grounded in the tradition.

There is a wide territory between the conventional expectations and assignments that come with preparation for graduate-level work in philosophy, on the one side, and the commercial model of education for which you have such contempt, on the other.

I have set out to explore that territory and, so far, I’ve found the exploration worthwhile.

You say: “Gingerbread house building is good in and of itself. It’s worthy of pursuit regardless of its practical benefits. But we probably shouldn’t fund a gingerbread house building department. If you want to build gingerbread houses, do it on your own dime.”

But gingerbread house building is *not* worthy of pursuit regardless of practical benefits. Gingerbread house building, if good, is good because it is fun. Humanities and arts however are worthwhile pursuits regardless of practical benefits. For that reason they should be supported by the public. The same kind of reasons that give us imperatives to have publicly funded art galleries give us reasons to have publicly funded humanities.

annonGrad:

Who gets to decide what’s worthy of pursuit? What makes humanities and arts worthwhile pursuits if there are no practical benefits?

Yes, we fund art galleries. Because people like to look at art. Right? An obvious practical benefit!

We wouldn’t, presumably, publicly fund an artist’s secret studio.

What is the art gallery equivalent in philosophy?

JD:

I was writing with the assumption that arts and humanities are pursuits of our most fundamental values that are not necessarily practical. I don’t think that I (or anyone else!) can justify that claim here. But those who share this assumption should be careful of giving in too much to the rhetoric of “What’s the practical worth in it for me?” from both students and administration.

Justin, thank ye for yer question.

I think the maths analogy (in one of the responses) is a mint one, except, in maths, the foundation, comes first, after, to bricks and mortar, before the escarpment begins to becoming a research mathematician. It is a methodical process where studying representation theory, for example, comes long after the bog standard courses that are necessary to dae so.

Why not 1) the same in philosophy with 2) the goal of teaching students how to handle themselves in the following, a thought experiment:

Imagine yourself at a talk. Imagine that in the audience sits a young Saul Kripke, up from Princeton that day, and, in the audience as well, a freshly minted Peter Singer from Oxford. Yes. The young Peter Unger is their, as well, already a full professor, and of course, the inimitable Derek Parfit is present. Parfit appears, always, to be at NYU; of course, at this time, his barnet is longer – much longer. There are many others at the talk including the wonderful Richard Martin, the sweet and dour William Ruddick, and the toodly Sara Ruddick.

Imagine that a third Peter is giving the talk: P.F. Strawson.

It does not matter what Mr. Strawson is yakking about – or, yeh can imagine that as well.

At the end of Mr. Strawson’s talk there is silence. Then, a hand goes up from the back of the room; it is Saul Kripke and the first pommy sentence out of his gob (taking into account Millianism) is:

“I don’t understand.”

Here’s the test: how would yeh graft with y’r students to bring em to the point of handling (managing, debating with) each person in this room, including, to start things orf, Saul Kripke and his position?

I believe, this is doing “representation theory” in philosophy. This is the “turing test” in philosophy. And, I believe that anyone brought to this level in philosophy can handle themselves in any situation outwith the wee world of academic philosophy – including all the other academic worlds that are ignored by philosophy inside and outwith of the Anglo-Saxon universe.

Please. This thought experiment should hae sod all to dae with caste, class, gender, race, or the fancy, including the glitter of the dickey bird “ toodly,” attached or not, to anyone of y’r students – or yourselves. I know it will be hard for us to imagine any scenario outwith of our own epistemological quarantines, our own ontological objects, but in this thought experiment, we must try. Also, for y’r information (in this thought experiment) Hannah Arendt was invited to attend, but chose – for her own reasons – not to attend.

One small example. A lot of schools offer a lower-level course in something like “contemporary moral problems.” This course typically starts off with a unit on moral theory, introducing students to deontological, consequentialist, and virtue-based moral theories. I have come to the view that this is a waste of time and no longer include such a unit in this course. I don’t see the value of students at this level knowing how professional philosophers have cut up the landscape, and I have no interest in them being able to tell me things like “deontologists would say such-and-such about policy P.” Better, I have found, for the beginning of such a class to focus on them developing a basic understanding of different kinds of things that may be of value, a basic understanding about how conflicts might arise between the promotion of and/or respect for competing goods, and a basic understanding of how argumentation works.

Justin, I’m considering a similar move in my contemporary moral problems-type courses for similar reasons. Do you have a particular text or texts you use that support the alternate approach you’ve described?

Why not introduce non-philosophy and even introductory students to professional philosophy? Students should become aware that fundamental questions that they may have thought not amenable to rigorous inquiry actually are subject to continuing lengthy and painstaking inquiry by persons who have expertise in these matters. Otherwise, why even teach philosophy at the undergraduate level? So-called “critical thinking” and other “transferable skills” can surely be taught via other disciplines preparing students for the actual applications of such skills in the workplace (insofar as these are so-called transferable skills, why not get a business or communications degree and transfer those skills to solve philosophical problems as a hobby?). Conversing about consciousness, evil, God, or whatever other philosophical topics without consulting or invoking the approaches of important canonical and contemporary philosophers can surely be done in the tavern without the burden of exams, papers, or “expert” professors to dampen the expression of opinion. Why even study philosophy if you’re not going to actually study philosophy at its professional best (acknowledging there will be debate over what counts as “good” philosophy and that course material should be appropriate to the level of the student)?

Well, yes, Avi, introduce students to top-flight contemporary philosophy, by all means . . . though in small doses, and as their work become relevant to some particular question or project or other.

That’s not the issue, though.

The question is whether we should design philosophy courses for undergraduates on the assumption that we are training them to join the ranks of professional philosophers, to write and think and speak as professional philosophers do in journals and at conferences.

(I’m not convinced professional philosophers should write the way we do in journals and speak the way we do at conferences, but that’s a topic for another day.)

Justin wrote: “This course typically starts off with a unit on moral theory, introducing students to deontological, consequentialist, and virtue-based moral theories. I have come to the view that this is a waste of time and no longer include such a unit in this course. I don’t see the value of students at this level knowing how professional philosophers have cut up the landscape . .. ”

I agree, up to a point. I really don’t care whether my students can recite any formulation of the Categorical Imperative at the end of class.

I would like them to know the difference between the right and the good, though, and maybe something about the idea of virtue.

As for texts, I find Anthony Weston’s “A 21st Century Ethical Toolbox” especially helpful, especially the way he introduces the idea of families of values, and uses that to set up a very accessible take on various ethical theories.

This is something I think about all the time. Thanks for raising it for discussion!

The undergrads I teach now are Medical Ethics students. Perhaps 1 or 2 in a class *might* apply to Philosophy grad school. 80-90% of the students are pre-med and will never take another philosophy class again. I try to expose them to a little bit of ethical theory because maybe a couple will be inspired by it and decide to pursue philosophy after all… but for the rest I know that this is essentially pointless. Of course, it’s not pointless for future MDs to engage with ethical issues! But it is pointless for them to spend time learning the technical lingo of academic philosophy. So I try to assign work that is mostly general audience friendly: textbooks, some NEJM or Journal of Medical Ethics, and the always-accessible James Rachels. But I don’t have them read straight philosophy journals. Those who aren’t philosophy majors won’t be able to parse that writing style, and there is little reason for them to learn how to do so.

My big question is about assessment. I’ve become convinced that writing philosophy papers is not a good idea for these students. Here’s why: (1) They don’t know how to do it. Even if they know how to write for other humanities, there are eccentricities to how philosophy is written (‘I will now argue…’ when students have been endlessly told by other profs not to use the word ‘I’ in academic prose…). It takes at least two or three attempts before students even start catching on, and by then the class is over. As a result, the few philosophy majors in the class always do MUCH better on essays than everyone else. It’s not fair that some students get better grades simply because they are used to the idiosyncratic conventions of disciplinary prose — grades should reflect what is learned in the course, not what is learned before it. (2) Those who do make the effort to learn how to write philosophical prose are not getting much out of it. They are never going to write in this way again. Now we might argue that philosophical writing teaches clarity of thought. Maybe. But I’m doubtful of that (whereas I’m *not* doubtful that learning how to philosophically analyze an argument is valuable in this way). For one thing, science students aren’t used to writing opinions. But they can figure out how to parrot the instructor’s views (or those of the textbook author) back in a paper convincingly enough to get an A-. From this they learn cautious mimicry, not creative clarity. More importantly though, philosophical writing involves quirks which are just bad writing outside of philosophy. For example I tell my students that they shouldn’t trouble about word variety — use the same word over and over for centrally important ideas, or else your seeming synonyms will cast variant connotative shadows and risk ambiguity in your argument. But that’s just bad advice for non-philosophical prose. The world would be a horrible place if everyone wrote like philosophers; Quine and Hemingway could carry off a taste for stylistic desert landscapes, but the rest of us just sound tedious. So why insist that our students develop skills that are only useful within a discipline they will never enter and are counter to good practice outside it?

So I have tried to stop assigning papers to my lower-level undergrads. But what do I assign instead? Exams, I guess. But the problem repeats: what kind of exam? Essay exams demand the same skills as essays, plus speed. “Objective” exams are better here, but kind of bizarre in context. (Look at the PhilPapers survey results – philosophers usually prefer ‘Other’ rather than the multiple choices.) So I’ve been stuck on this point. How do I fairly assess students in a philosophy class who have never before studied philosophy and will never do so again?

I often teach with the following thought in the back of my mind: “Some of these students might one day be on a university board with the power and ability to cut philosophy from their program. Will s/he think, “Man, I remember how valuable my philosophy class was. It made me think about things in ways I’d never thought about before; it taught me to ask questions; it taught me how interesting the world really is. I definitely don’t think we should cut it.” or “Yes, it’s a waste of time. I remember the professor droning on and on about worthless stuff. We don’t need it.”

This pushes me to care just as much about nurturing in my students an appreciation of philosophy AS WELL as teaching them content and skills. (I don’t always succeed.) So, I often don’t think of my students as future professional philosophers (since that thought is false) but as future citizens who will be in a position to encourage others and themselves to engage in the valuable project of philosophy.

I haven’t taught yet, but I have been a TA and I also have experience in the real world. And I can say that I have started to recognize a worrisome pattern: profs treat undergraduate students like kids. I have seen profs give out extensions following really poor excuses at the last minute, and I have seen them make crazy exceptions (e.g., you handed your assignment in one month late but didn’t realize it was supposed to be handed in online instead of in class? No worries! I won’t deduct anything.) Perhaps this is because profs see undergraduate students as really new to university compared to how long their graduate students have been there, I’m not sure. But the reality is that these students aren’t kids. They are professionals-in-progress, and they will be competing for jobs in the real world in a few short years. When they do, they will need time management and organizational skills just as much as they will need critical thinking skills that come hand and hand with a philosophy degree. So I think that we should think not just about how we can teach philosophy in ways that will be applicable to students’ diverse futures, but also how we can teach in ways that will help students develop a good work ethic and other skills that are required for most careers.

This is such a great question. I believe you can teach students very sophisticated, rigorous, philosophical skills. Never underestimate your students. I also think that there are lots of philosophical subjects that have been placed outside the main ‘M&E, M&L, plus Ethics’ curriculum where very sophisticated, rigorous, philosophical thinking, teaching, and learning are done and can be done: philosophy of education, aesthetics, and so on. And many of these subjects are great opportunities to get students into doing philosophy with enthusiasm and interest. It’s not that they are more practical, or useful. It’s just that more students, on average, get more excited about them than, say Frege. I love Frege. But I’m a professional philosopher. If it gets them on board, who knows where it will take them, but learning how to think philosophically is a good thing. I don’t much care what the occasion is for such thinking because I don’t think that good philosophical thinking is confined to a narrow range of philosophical subjects.

On another note, the sneering at teaching is a pretty deep problem for us. I worry that it is a reflection of the pernicious attitude that philosophers are born, not taught. In that sense, it is connected to some of the wider professional issues that we’re concerned with now.

Thanks for this thread, it raises an interesting and important issue for any undergraduate philosophy class. I disagree a bit with the premise, however. In particular, I’m not at all convinced that there is, or should be anyway, too much of a gap between ‘pre-professional’ and ‘amateur’ philosophy courses. After all, insofar as we’re talking about lower-level undergraduate teaching, even more professional courses would have to make pretty serious allowances for the students’ academic backgrounds and interests. I also find some of the explanations in the above thread of this difference and esp. of the best way to solve it quite opaque. E.g., I don’t really see what Bob Kirkland has in mind when as an example of a non-professional approach he writes: ‘The goal, at least for me, is to make serious, critical, philosophical thought something that is vital and engaging for students in disciplines other than philosophy (i.e., all of my students), but in a way that is rigorous and grounded in the tradition.’ So described, it sounds like his goal is to teach a ‘professional’ course in an engaging and successful way, unless perhaps he is using the phrase ‘rigorous and grounded in the tradition’ in a highly deflationary and idiosyncratic way. After all, who wouldn’t want to take a graduate course or to attend a professional talk which fit that definition?

A small defense of Tait @2: sarcasm usually requires something taken taken seriously as its object (why else use it?); he was more overtly questioning in rhetorical question form, as Justin was more sarcastically, who would take such a position seriously in the first place. There’s no harm and no foul here.

How about teaching our students on the assumption that they can do philosophy and be philosophers without pursuing philosophy as a profession (or even, necessarily, as a major)? Without that supposition, I’m not sure what we think we’re doing in general education classes anyway.

Hypocrates: Regarding essay assignments. I think students can learn a way of thinking – and a way of using writing as an aid to thinking – from philosophical essays that is applicable outside of philosophy. Learning to write a philosophical essay involves learning to think about arguments in a way that is useful in other disciplines, even if the specific writing task in those disciplines may be different.

As for the fairness issue, one way to do things is to provide structured essay assignments that lead students through the process of structuring a philosophical essay. I’m sure others have done this better, but you can find an example of how I’ve done it for an intro to ethics class here: http://derekbowman.com/teaching/sample-course-materials/

I can usually detect your sarcasm, Justin, but I honestly missed it this time. My bad.

Don’t feel guilty about being a good teacher. You’ll teach best when you are intellectually engaged with what you are teaching. Since you are an academic, what intellectually engages you is more likely than not to be the sort of the thing that typically intellectually engages academics.

From your description of the “contemporary moral issues” course it sounds as though the problem was that it didn’t encourage students to think philosophically either about the applied issues or about the ethical theories in question. That is, it didn’t treat the students as though they were capable of doing philosophy, rather than just learning about it.

I think the (delightful) illustration you chose might be misleading, at least to the extent that I don’t think the options are teaching our students to become professional philosophers, or ensuring that philosophy prepares students exactly for whatever is currently fashionable in the marketplace. Rather, I think the question is just this: how would we design a philosophy course for non-specialists if we knew this was their one opportunity to do philosophy?

I’m not sure of the answer to this question, but this semester I’m teaching a course on contemporary moral problems, I’ve turned it into a course that focuses just on ethical issues related to food (in part because the university is sponsoring a series of talks on food.) Assignments include exams and online discussions, but also a reflective project where they have to do something (e.g., go vegan for a weekend, among other options) and write an essay about it. We’re still learning about ethical theories, and how to argue well, but it will be (I hope) a little less of the “one argument for, one argument against, the end” structure that’s easy to fall into at the intro level.

We teach undergraduates that way (that is, as though we were preparing them to become professional philosophers) because we want to replicate ourselves. Take it from Plato, actually Diotima, who puts it like she sees it: we all want (she’s taking about men really) to give birth and beget “in the presence of beauty,” because, well, who doesn’t prefer the children of Homer to the ones that get headaches and toothaches, and bad times too…

Um, I like my actual children just fine, thanks. They’re very fine humans-in-development, and my only concern is that they grow to be healthy, independent, thoughtful, slightly skeptical and responsible adults.

I suspect neither of them will end up in academia, and bless them for it.

Yes, though, I suspect you’re right: there is some yearning for self-replication in the conventional approach to teaching philosophy. My contention would be that it’s not an especially healthy obsession, and that it serves our students and our profession poorly, in the long run.