Comfortable With a Kind of “Stupidity”

At some point, the conversation turned to why she had left graduate school. To my utter astonishment, she said it was because it made her feel stupid. After a couple of years of feeling stupid every day, she was ready to do something else. I had thought of her as one of the brightest people I knew and her subsequent career supports that view. What she said bothered me. I kept thinking about it; sometime the next day, it hit me. Science makes me feel stupid too. It’s just that I’ve gotten used to it. So used to it, in fact, that I actively seek out new opportunities to feel stupid. I wouldn’t know what to do without that feeling. I even think it’s supposed to be this way.

That is from a short piece, several years old, by Martin A. Schwartz, a microbiologist at UVA, though it is easy to imagine the same kind of conversation between a philosophy professor and former philosophy student. One interpretation of that passage is that Schwartz is saying that the student wasn’t tough enough to survive the acculturation process through which good academics get used to being “stupid” (“ignorant”?) in the way he describes. That may be what he is saying, but he does not blame the student. He thinks it is a failure of graduate education:

I’d like to suggest that our Ph.D. programs often do students a disservice in two ways. First, I don’t think students are made to understand how hard it is to do research. And how very, very hard it is to do important research. It’s a lot harder than taking even very demanding courses. What makes it difficult is that research is immersion in the unknown. We just don’t know what we’re doing. We can’t be sure whether we’re asking the right question or doing the right experiment until we get the answer or the result.

Second, we don’t do a good enough job of teaching our students how to be productively stupid – that is, if we don’t feel stupid it means we’re not really trying. I’m not talking about ‘relative stupidity’, in which the other students in the class actually read the material, think about it and ace the exam, whereas you don’t. I’m also not talking about bright people who might be working in areas that don’t match their talents. Science involves confronting our ‘absolute stupidity’. That kind of stupidity is an existential fact, inherent in our efforts to push our way into the unknown. Preliminary and thesis exams have the right idea when the faculty committee pushes until the student starts getting the answers wrong or gives up and says, `I don’t know’.

There is something to this. Professors set a bad example when they don’t own up to their own intellectual struggles, lack of confidence, and ignorance. And it seems like graduate programs could do more to help students to deal productively with feelings of “stupidity” (and to not let it contribute to impostor syndrome). Yet Schwartz only notes in passing, towards the end, that people are differently situated in their capacity to do this. Admitting to peers, professors, and advisers that you feel stupid is an expenditure of intellectual and social capital, and how comfortable you are doing that may depend on how much of such capital you have in the bank—and that, in turn, might depend on all sorts of arbitrary and unfair features of our lives and world. So there may be more to addressing the problem than Schwartz accounts for here. Nonetheless, it may be worth considering how departments can help students make better use of feeling “stupid.”

(Thanks to Kareem Khalifa for bringing this article to my attention.)

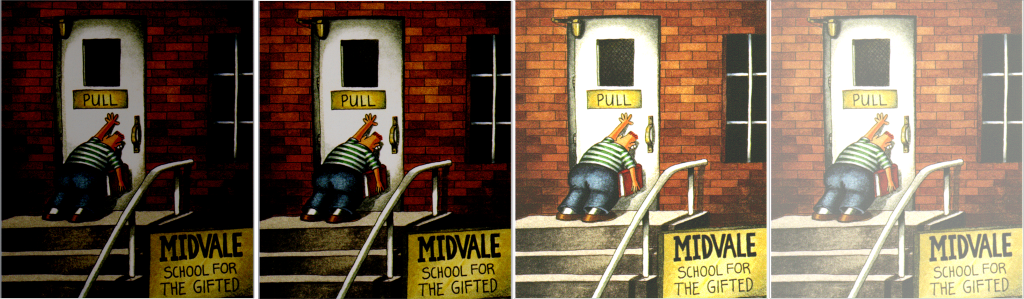

(art: Gary Larson, The Far Side)

This is an excellent point. I often tell my (undergraduate) students that if they aren’t sometimes confused by passages in the assigned readings they aren’t trying hard enough. But the point scales up to all levels of philosophical education and practice.

It’s also worth keeping in mind the way that pressure to publish in prestigious venues as graduate students and the need to be ‘exceptional’ as job candidates further exacerbates this problem. e.g., “Oh man, I’m already in my 5th year and I still can’t get a paper into Ethics or Phil Review; maybe I’m just not cut out for this.”

I’m sympathetic with all of this, but I’d like to keep ‘ignorant’ and ‘stupid’ separate. I’m not sure how to articulate it – this in fact is itself an example of the ‘stupidity’ I’m trying to differentiate from ignorance – but I’ll give it a go.

To be ignorant is to not know something because you’re insufficiently well-read or because time is limited or whatever. To be stupid is to fail to see something which is – how do I put it – ‘there for you to see’, ‘right in front of your face’, ‘something you would be able to see if you were smarter’. If you can’t make sense of a text, or work out how to fix an argument, because you’re lacking in the requisite historical background or because the concepts are esoteric and only come from a certain deep shift in your way of looking at things, then you’re not culpable, and you can put your incomprehension down to ignorance. But the philosopher’s (researcher’s?) lot (or maybe it’s just my lot, and I really am stupid! I’ll assume not with fingers crossed) is to constantly make mistakes that cannot be so excused. It is to just miss a crucial sentence in a paper and so get the whole thing wrong, it is to use a term in two completely different ways in your premisses and your conclusion, it is to work at an argument for months and years before realising that you’ve made a crippling mistake that any half-competent philosopher could have pointed out. And when the philosopher that you regard as only half-competent DOES point out this mistake that unravels your paper of which you were so proud, you do feel stupid, and there’s a very real sense in which indeed you are stupid. The only objective standard we have in philosophy is truth, and that is infinitely distant. (There are jobs and awards and so on, but they’re just proxies.) We can never go beyond what is required of us (sc., find the truth), we can only fail to greater or lesser degrees; and for the most part, that failure is a failure, not of learning or whatever, but of intelligence.

For what it’s worth, my solution to this, for my own sanity, has to been to stop thinking about stupidity. I contain my Schadenfreude when a world-renowned scholar makes an elementary slip, and I don’t let myself beat myself up when I make such a slip myself. But the urge to compare oneself is strong.

I notice on looking over this comment a host of errors, confusing ambiguities, infelicities, etc. If anyone asks, they’re deliberate illustrative cases in point.

A very nice post. I especially agree with some of the points you make in the final paragraph. However, my experience in making much the same points is that some people are determined to mistake them for condescension and have no qualms about responding with castigation and mockery. So I’ve simply given up.

Professors owning up to their own sense of stupidity goes a *long* way towards creating an environment in which one can be comfortable feeling stupid. Grad students don’t have an easy view into your actual, first-hand experiences, especially just how much time you spend feeling out of your depth with something, or annoyed that the words just aren’t coming together quite right, or vaguely haunted by the sense that there must be something you’re missing. From our point of view (especially when we’re just starting out), Actual Philosophers can seem like a different type of creature from the messy humans that we are, and the task of grad school is somehow to morph into one of these creatures who has read everything (or at least everything important), who is completely confident with every claim they make, and who always knows exactly what they’re doing. It can be *so* relieving to see that the people you admire and who seem obviously brilliant (and who have managed to have a career in this field!) are actually humans too, just ones who have spent a bit more time on this stuff than you.

NB: Just admitting that you don’t understand something may not be quite enough, though — you want to make sure that people grasp that you mean “I don’t understand this [but I feel like I should]” rather than “I don’t understand this [so it’s probably nonsense].”

I am also a person who chronically “feels stupid.” Two discoveries (the first told to me by an undegrad professor, the second learned on my own) have made things a bit easier for me:

(1) Philosophy is a field of giants. Even pretty successful philosophers are “relatively stupid” in comparison with the field’s defining figures. The appropriate response to working in such a field is awe and humility. It’s your classmates and profs who don’t exhibit such a response who are the problem, not you.

(2) Producing interesting and sophisticated philosophy is not simply a matter of being brilliant on your feet, but of being able to sit down every day for several months or even years and really think through a problem. Often though being good at philosophy is confused with the former quality.

I would add that those ‘giants’ were themselves simply human beings applying their limited knowledge and abilities in an attempt to make sense of the human condition and of the philosophical traditions they had inherited. No doubt some were so egomaniacal as to never be humbled by the questions they were wrestling with, but I suspect they are in the minority.

Here’s an illustrative passage from the conclusion of John Rawls’s “Some Remarks About My Teaching” (partially reprinted in the Editor’s Forward to his Lectures on the History of Political Philosophy. (p. xv-xvi):

“Yet, as I have said, I have never felt satisfied with the understanding I could gain of Kant’s overall conception. This leaves a certain unhappiness, and I am reminded of a story about John Marin… Marin’s paintings … are a kind of figurative expressionism. In the late forties he was highly regarded as perhaps our leading artist, or among the few. … For eight year in the 1920s Marin went to Stonington, Maine, to paint and Ruth Fine, who wrote a splendid book on Marin, tells of going there to see if she could find anyone who had known him then. She finally found a lobsterman who said, ‘Eeah, eeah, we all knew him. He went out painting in his little boat day after day, week after week, summer after summer. And you know, poor fellah, he tried so hard, but he never did get it right.’ That always said it exactly for me, after all this time ‘Never did get it right.'”

Another way of conveying something similar is to point out how boring, pointless and trivial most published philosophy papers are. Those papers are the best that most ‘successful’ philosophy professors can achieve…

I found that while in graduate school, when I admitted the “good” kind of stupid, professors would inevitably remark that I needed to be more confident and point to people fully committed (often to bad arguments) as a role model. I chalked it up to being a woman-and that admitting weakness/not knowing was interpreted as a sign of my incompetence. And I got very tired of that, and left.